Home | Category: Art and Architecture

HELLENISTIC SCULPTURE

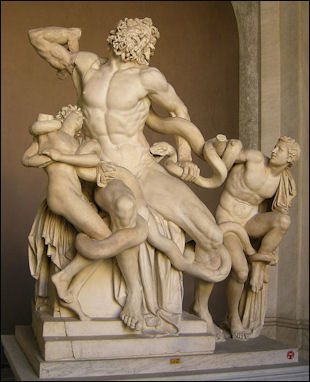

The Laocoon, a Hellenistic

period work Hellenistic Sculpture (323 B.C. to 31 B.C.) was much more varied and exquisitely-produced than sculpture made during the Classical period. Some of the most beautiful pieces of Greek statuary, including the Nike of Samonthrace, the Dying Gaul, Apollo Belvedere , and the Lacoön Group, date back to Hellenistic times. The Dying Gual has the hair and facial features of an ethnic Gaul.

The Lacoon, now at Vatican Museum, features a father and two sons struggling to entangle themselves from the grasps of giant serpents. The 2000-year-old statue depicts the punishment meted out to a priest who warned the Trojans to beware of Greeks bearing gifts.

Adam Masterman, wrote in Quora.com: During the Hellenistic period (323031 B.C.) sculpture fully embraced naturalism. Figures look like individuals instead of ideals, and a full range of emotions and actions are portrayed. Poses are the most diverse of any of the periods, representing a wide variety of actions and physical states. The anatomical detail is the most closely resembling real bodies (and thus the least idealized), and particular attention is paid to how bodies morph and change in different positions, showing a strong tradition of empirical observation. Finally, the work is more ornate than in any other period, reflecting a preference for complexity of design that can also be seen in the architecture of the time.

“Apollo Belvedere” , also at the Vatican Museum, glorifies the male body. Described by one critic as "a symbol of all that is young and free strong and gracious," it is most likely a Roman copy of a Greek bronze made by Leochares around 330 B.C. The original once stood in the Agora in Athens but is now lost. The copy lacks its left hand and most of its straight arm and scholars believe the right hand held a quiver and the left hand a bow. The elegant cloak is still in place. For several centuries it had a fig leaf over private parts.

“Apollo Belvedere” stood for four centuries in a niche in the Octagonal court of the Vatican until it was taken by Napoleon's army in 1798 and kept in Paris until 1816, when it was returned. It was said Napoleon that coveted it more than any other booty because it was considered the embodiment of the high culture of classical Greece.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hellenistic Sculpture” (World of Art) by R. R. R. Smith (1991) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic and Roman Ideal Sculpture: The Allure of the Classical” by Rachel Meredith Kousser (Author) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Art: From Alexander the Great to Augustus” by Lucilla Burn (2005) Amazon.com;

“Understanding Greek Sculpture: Ancient Meanings, Modern Readings”

by Nigel Spivey (1996) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture” by John Boardman (1978) Amazon.com;

“Parthenon Sculptures” by Ian Jenkins Amazon.com;

“How to Read Greek Sculpture” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) by Sean Hemingway (2021) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Sculpture: An Image Archive for Artists and Designers” by Kale James Amazon.com;

“The Interpretation of Architectural Sculpture in Greece and Rome” by Diana Buitron-Oliver (1997) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Ancient Sculpture, Egyptian – Assyrian – Greek – Roman: With One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations” by George Redford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques” by Janet Grossman (2003) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art: Art and Thought in Ancient Greece”

by Ian Jenkins (2015) Amazon.com;

“Esthetic Basis of Greek Art” by Rhys Carpenter (1921) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture. Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Olga Palagia, editor (Cambridge University Press, 2006); Amazon.com;

“The Technique of Greek Sculpture in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Sheila Adam (1966) Amazon.com;

“Classical Art: From Greece to Rome (Oxford History of Art) by Mary Beard, John Henderson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Art” (World of Art) by John Boardman (1964) Amazon.com;

Nike of Samonthrace

“Nike of Samonthrace”, at the Louvre, is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of Greek art. Wings spread wide into a headwind that blows her clothes against her headless body, an image that later would grace the bow of many ships.

Apollo Belvedere Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: Since it was first displayed in 1883, two decades after its discovery, the nine-foot-tall marble statue of Winged Victory has awed visitors to the Louvre. In the sculpture’s original location above the theater in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace, the winged goddess Nike would have been equally captivating. “The statue was most brilliantly sited,” says archaeologist Bonna Wescoat of Emory University. “Standing where she once stood, you have this extraordinary sight line right down through the heart of the sanctuary.” For archaeologists, though, details about the monument’s dedication and ancient context are obscure. Renewed studies in recent years conducted by an international team of scholars are offering new leads. [Source Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2021]

Nike is depicted alighting on a warship’s prow that served as the sculpture’s base. A preliminary reconstruction from fragments of a stone ram, a battering device designed to pierce an enemy’s ship, that once protruded from the prow’s front has prompted the team to reconsider who was responsible for the monument’s dedication. The prow is made of blocks of Lartian marble, a blue-gray stone with pink and white veins that was quarried on the coast of the island of Rhodes. In addition to the Nike monument, Greek sculptors used Lartian marble for monumental prow bases erected on Rhodes and the nearby island of Nisyros. One of these bases is strikingly similar in scale and construction to the Nike statue’s base. Based on this, the researchers believe the Rhodians were involved with the monument, which surely commemorated a sea victory sometime in the second quarter of the second century B.C. “Rhodes was a huge sea power, and we know that the Rhodians were active in the sanctuary,” Wescoat says. “It would make sense for them to use this kind of prow as a base.”

See Separate Article: CULT OF THE GREAT GODS AT SAMOTHRACE europe.factsanddetails.com

Venus de Milo

“The Venus de Milo” is arguable the world’s most famous sculpture and may be the second most famous work of art after the “Mona Lisa”. Thousands check it out daily in the Louvre, where it has stood for more than a century. It has been sketched, copied, debased and lampooned, Among the artists who have been inspired by it and/or placed it in their own works have been Cezanne, Dail and Magritte but at the same time it has been debased in advertisement and kitschy souvenirs . When she came to Japan in 1964 more than 100,000 people came to greet the ship that carried her and 1.5 million filed past on a moving sidewalk that ran past where she was displayed. [Source: Gregory Curtis, Smithsonian magazine, October 2003]

Venus de Milo The “Venus de Milo” was originally carved in two parts, with the two halves concealed by the fold of drapery circling her hips. The pedestal and the arms have been lost. No one is sure how the arms were posed. Some believe the upraised arm rested on a pillar. Others believe it may have held a shield. Yet others believe it may have held an apple found near the statue.

After the statue was brought to the Louvre restorers tried to attach plaster arms in all conceivable positions — carrying robes, apples and lamps or just painting here and there. None of which looked right. It was thus decreed that the "work of another artist must never mar her beauty" which set a worldwide precedent. From then on classical works of art were never monkeyed with again.

History of the Venus de Milo

The Venus de Milo was found in 1820 by a peasant in a cave on Melos, a Greek island in the Aegean Sea about halfway between Crete and the Greek mainland (her name means “Venus of Melos”). It was then claimed by French archaeologists and bought by French officials for the relatively paltry sum of 1,000 francs, which was paid to the Ottoman Turkish overlords of Greece. After it was displayed the Germans claimed the statue was there as it was unearthed on land purchased by Crown Prince Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1917.

Sculpted around 100 B.C., the Venus de Milo was found in two parts, along with pieces of the arms and a pedestal. The French originally thought it was made by the master Phidias or Praxiteles, until it was discovered it was inscribed with the name “Alexandros, son of Menides, from the city of Antioch on the Meander". Compounding the disappointments was the fact it was produced after the classical period (statues made in the Hellenistic period were considered inferior to those made in the classical period). Not to worry the base with the name on it was simply made to disappear. However drawings made when the base was still in existence and the debate on whether it was a classical piece or not entered the dispute between France and Germany as to who owned. To this day the Louvre remains a little embarrassed by the whole issue.

Early in the 20th century reference to Alexandros of Antioch were found in Thespiae, a city near Mount Helicon on the mainland of Greece. It turns that Alexandros was more than just a sculptor. An inscription dated to 80 B.C. identifies Alexandros of Antioch, son of Menides as the winner of a singing and composing competition.

Dancing Satyr of Mazara

The “Dancing Saytr”, one of the greatest artworks from the Ancient World, was caught in a Sicilian fisherman’s net in 1998. It is usually housed in a dedicated museum in the fishing town of Mazara on the west coast of Sicily. “David Ekserdjian, professor of art history at Leicester University, said that the sculpture had forced experts to rethink their view of the Greek world and hailed it as “absolutely up there” with later masterpieces such as Michelangelo’s David and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. [Source: Ben Hoyle, August 16 2012, The Times]

Katharine Earley wrote in Italy Magazine: “The satyr appears to be leaping forward in an ecstatic move, its back arched and head thrown back. A symbol of revelry and wild, hedonistic abandon in classical times, historians and archaeologists have pondered whether it could have been a figurehead for a boat, due to the round hole in its back. Satyrs formed part of the raucous entourage of Dionysus, the greek god of wine, who was associated simultaneously with divine bliss and brutal rage. According to Greek mythology, the satyr may well have held a cup of wine in one hand, with a panther’s skin slung over his arm, and a staff in the other, tipped with a pine cone and twined with ivy. [Source: Katharine Earley, Italy Magazine, June 6, 2012]

It is commonly thought that Mazara’s satyr was made by the ancient Greeks in the 2nd and 3rd B.C. The statue itself is beautifully well preserved. It weighs 96 kilograms and reaches a majestic height of two meters. Both of its arms are missing, while one leg, bent backwards as if running, was recovered separately. “Scientists spent more than five years restoring the statue at the Istituto Centrale per il Restauro in Rome. Through a painstaking process of cleaning and chemical treatment, they have managed to uncover much of its original beauty and character, and curb any damage caused by exposure to the air. They also inserted a metal frame inside the satyr, so that it could be displayed upright.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024