Home | Category: Culture and Sports

GAMES IN ANCIENT GREECE

“Five-lines” was a game of skill, with an element of chance . The defence of the stones on their lines or squares depended on the throwing of dice. But even here there seem to have been modifications, which would enable a skilful player to compensate himself for an unfavorable throw, by the choice of various moves open to him.

The invention of draughts was ascribed to Palamedes, one of the heroes of the Trojan War, a story which at least proves that they were played in Greece in very early times. Nuts and coins were also used as counters in various games, and games of dice were played in various ways. Dice, identical to ones in use today, were found in Egyptian tombs dating back to 2000 B.C. Almost all the ancient civilizations used dice, which developed from astragali (See Below). Astragals could be used as dice, and had the advantage of needing no marks, as the sides were naturally different.

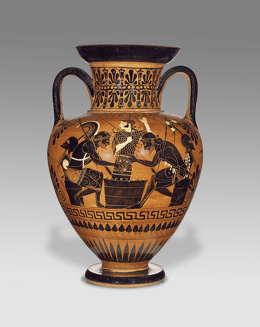

Another favorite game was similar to morra, still popular in Italy. Two players quickly thrust out their right hands with some fingers bent in and others stretched out, and they have at one glance to notice and exclaim how many fingers of both hands together are stretched out. This game is often represented on ancient works of art; for instance, on one vase painting. Here a youth and a girl are playing, both are seated, though morra players of the present day stand; in their left hands they hold a stick, the object of which is to prevent them in the excitement of the game from using their left hands by mistake. Similarly the Italians put their left hands behind their backs while playing. The youth is stretching out four fingers, the girl two, so that the number to be called out in this case is six. A Cupid seated above is handing a wreath to the girl, and thus pointing her out as victorious.

Astragali (Knucklebones)

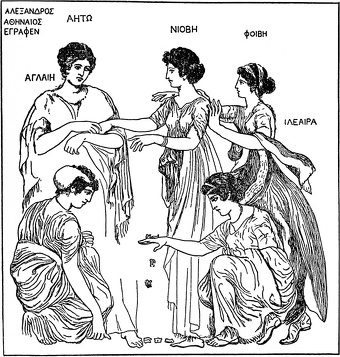

Astragali (knucklebones) — six sided bones, with four flat sides, that came from the ankle bones of hoofed animals such as sheep and goats — could be used like dice or “jacks”. When they were used like jacks they were thrown up and caught on the back of the hand. A toilet box shows three women playing, one of whom has an astragal on the back of her hand. The knob on the cover of the box is appropriately made in the same form. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Astragali were used in board games by Egyptians, possibly as early as 3500 B.C. The bones from sheep were most commonly used. Those from antelope were particularly prized. In ancient Greece, there were several ways of playing with astragals, which could be made of artificial material imitating the ball of the ankle-joint of sheep. One way of playing, chiefly used by children, but also sometimes by grown-up people, was a real game of skill, and consisted in throwing up a number, usually five, of knuckle-bones, pebbles, beans, coins, etc., and catching them again on the back of the hand, Meanwhile picking up with the stretched-out fingers those which had fallen down. Sometimes they only played “odd or even,” and one of the players had to guess straight away whether the other had an odd or even number of these astragals, which took the place of our counters, in his closed hand. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Sometimes they played with astragals in the same way as with dice. In this case the four large sides of the bone, on which it might fall, had a particular numerical value, which was not written upon it, but depended on the shape of the bone, as each side differed from the others. The convex narrow side counted as one, the other, concave, narrow side as six, the broad convex side as three, and the broad concave side as four; two and five were wanting altogether, for the other little surfaces of the bone were not counted, since it could never fall upon them. Four pieces were generally used for playing, and they were treated just like dice; the best throw was that in which each of the astragals lay in a different position, and thus all values were represented, sometimes they counted according to the highest number thrown. In works of art we very often see girls playing astragal. One of the prettiest of these is the terra-cotta figure from Tanagra.

Inscribed knucklebones or astragali made from goat, sheep, and cattle bones, dated to the 4th to 2nd century B.C. and measuring about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) long and 0.4 centimeters (0.2 inches) tall, were found in Maresha, southern Israel. Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: For the residents of ancient Maresha animal bones that may seem like useless leftovers destined for the trash heap were used to play games and as a way to contact the gods. Archaeologists working in a series of man-made caves in the lower part of this once-bustling Hellenistic metropolis have uncovered more than 600 astragali, or knucklebones. Caprids such as sheep and goats, as well as cows and pigs, have knucklebones that are six-sided and symmetrical, and thus were frequently used as dice throughout much of antiquity. Although astragali are commonly found at sites across the world, such a large collection is otherwise unknown in sites dating to the Hellenistic period in the Levant. As the knucklebones were used for entertainment, gaming, and religious purposes, explains archaeologist Ian Stern of the University of Haifa, the popularity of astragali speaks to the life of a cosmopolitan city inhabited by local Idumaean people living side by side with Arabs, Phoenicians, Macedonians, and Egyptians. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2022]

Many astragali were smoothed and polished to make them easier to roll. Others were pierced and filled with lead to make them heavier and thus prone to scatter more evenly whether tossed on a table or thrown in the air. Some were made of glass or bronze and others were engraved with letters, inscriptions, or geometric shapes. A number of the Maresha astragali are inscribed in Greek with the names of goddesses and gods. These include Nike, the goddess of victory — the word “Nike” can also mean victory when used on its own — and Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, both deities of love, as well as Hera, the patron goddess of marriage. “While astragali were commonly used for gaming and gambling,” says Stern, “many of those discovered in Maresha were found in contexts with altars, divination texts written in Aramaic, and other cultic materials that suggest they were used in a ritualistic manner.”

Kottabos, an Ancient Greek Drinking Game

“Kottabos” is one of the world first known drinking games. A fixture of ancient Greek symposiums and all-night parties and reportedly even played by Socrates, the game involved flinging the dregs left over from a cup of wine at a target. Usually the participants sat in a circle and tossed their dregs at the basin in the center. The game was so popular that ancient Greeks built special round rooms where it the game could be played, so all competitors were equidistant from the target. It has been suggested that after centuries of being played it died out because it was such a mess to clean up afterwards.

Kottobos is said to have been introduced from Sicily. Critias, the 5th century academic and writer, wrote about this “glorious invention” stemming from Sicily, “where we put up a target to shoot at with drops from our wine-cup whenever we drink it.” While a handful of modern academics question the game’s Sicilian origins, kottabos definitely spread throughout parts of Italy (as the Etruscans played it) and Greece, too. It fell into disuse during the age of Alexander’s successors, and was unknown to the Romans.

Megan Gannon wrote in Live Science, “At Greek symposia, elite men, young and old, reclined on cushioned couches that lined the walls of the andron, the men’s quarters of a household. They had lively conversations and recited poetry. They were entertained by dancers, flute girls and courtesans. They got drunk on wine, and in the name of competition, they hurled their dregs at a target in the center of the room to win prizes like eggs, pastries and sexual favors. Slaves cleaned up the mess. [Source: Megan Gannon, Live Science, January 14, 2015]

“Ancient texts and works of art indicate that there were two ways to play kottabos. In one variation, the goal was to knock down a disc that was carefully balanced atop a tall metal stand in the middle of the room. In the other variation, there was no metal stand; rather, the goal was to sink small dishes floating in a larger bowl of water. In both versions, participants attempted to hit their target with the leftover wine at the bottom of their kylix, the ancient equivalent of a Solo cup.

“The red-and-black kylixes had two looped handles and a shallow but wide body — a shape that perhaps was not the most practical for drinking but lent itself to playful decoration. Big eyes were sometimes painted on the underside on kylixes so that the drinker would look like he was wearing a mask when he took a hefty sip. And the relatively flat, circular inside of the cup, called the tondo, often carried droll or risqué pictures that would be slowly revealed as the wine disappeared. The tondo of one kylix at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston bears the image of a man wiping his bottom. Another drinking cup at the same museum shows a man penetrating a woman from behind with the caption “Hold still.”

“Other paintings on kylixes were quite self-referential, with scenes of revelers playing kottabos. Based on those ancient illustrations, researchers had assumed that to play the game, you would swirl the dregs in the kylix and flick them at the target, almost as if you were doing a forehand throw with a Frisbee. But her experiment showed that that was not the most winning technique.

“Elite Greek women wouldn’t have taken part in symposia, but there are some indications that the courtesans, called hetairai, would have played kottabos with the men. “Another thing we quickly realized is, it must have gotten pretty messy,” Sharpe said. “By the end of our experiment we had diluted grape juice all over the floor. In a typical symposium setting, in an andron, you would have had couches arranged on almost all four sides of the room, and if you missed the target, you were likely to splatter your fellow symposiast across the way. You’d imagine that, by the end of the symposium, you’d be drenched in wine, and your fellow symposiasts would be drenched in wine, too.”“

Playing Kottabos

Francisco Javier Murcia wrote in National Geographic History: After finishing his cup, the guest picked it up by the handle and flicked the dregs at a target, usually another cup. As he did so, he uttered the name of his beloved, as it was believed that hitting the target boded well for his love life. There were more elaborate variants of the game: In one of them, the guests tried to sink small clay vessels floating in a large cup; in another, they shot at a saucer balanced on a metal bar. Xenophon writes how in 404 B.C., Theramenes, an aristocrat who had been condemned to death, proved his sangfroid by parodying the kottabos ritual with the cup of hemlock he had been forced to drink. According to Xenophon, he cried out: “To the health of my beloved Critias” (the name of the man who had condemned him to die). [Source: Francisco Javier Murcia, National Geographic History, January-February 2017]

Jim Clarke wrote in atlasobscura.com: The preferred way to play kottabos, “which is the iteration often depicted in plays and especially on pieces of pottery, involved a pole. Players would balance a small bronze disk, called a plastinx, on top of it. The goal was to flick dregs of one’s wine at the plastinx so that it would fall, making a clattering crash as it hit the manes, a metal plate or domed pan that lay roughly two-thirds down the pole. The competitors reclined on their couches, arranged in a square or circle around the pole a couple of yards away. Each then took turns launching their wine from their kylix, a shallow, circular vessel with a looping handle on each side. [Source Jim Clarke, atlasobscura.com, February 19, 2018]

A less common version of the game featured players aiming at a number of small bowls, which floated in water within a larger basin. In this case, the object of the game was to sink as many of the small bowls as possible with the same arcing shots. Since it lacked the resounding clang of the plastinx striking the manes, this version of kottabos has been regarded as the quieter, more civilized way to play.

Technique was essential to maintain elegant form, accuracy, and to avoid spilling on oneself. The player, sprawling on a drinking couch and propped up on their left elbow, placed two fingers through the loop of one handle and cast the wine dregs in a high arc toward the target. The technique has been likened to the motion of throwing a javelin, due to the way the player threaded their fingers through the handle the same way one held the leather strap used to throw the spear.

The cup was held, not by the foot, but by one handle with the fingers, and they did not use the whole arm in throwing it, but only the wrist, or, if the arm was bent, only the lower arm. There were various ways of playing this game; for the commonest, they seem to have used a stand something like a high candelabrum, the shaft of which could be screwed higher or lower according to requirement. On the top of it was balanced, placed loosely upon it, a little saucer or bowl of brass, and the wine which was thrown had to fall with a ringing noise upon it, and throw down the disc; it is clear, from various vase paintings, that this was not fastened to the top, since we see girls in the act of laying the disc on the top of the shaft. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

This, however, was not enough; various complications were added to increase the difficulty. On some of the kottobos stands they fastened the figure of a slave, called “Manes,” made of brass, which must also be struck in throwing, and according as it was fastened on the shaft, either first or last. Sometimes the disc on to which the wine was thrown must, when struck, fall down on to another small scale fixed a little lower down, and the sound then made, according as it was strong or weak, was regarded as a kind of oracle in love. In one image, the bearded man lying on the couch is in the act of throwing the wine left in his cup, which he holds by the first finger of the right hand, at the kottobos stand.

Near him lies a youth with a thyrsus, who is handing fruit, or something of the kind, to a woman with a tambourine, sitting on a cushion in front of him. On the right is a cup-bearer, a naked boy with a wine can. Sometimes they seem to have spirited the wine from their mouths instead of from a cup; or they set little saucers or nut-shells to swim empty on the water, and tried to fill them by throwing in the wine drops and making them sink. This occupation, in spite of the great popularity it seems to have had in the fifth and fourth centuries, can but be regarded as a very unintellectual one.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Nonetheless, these were not high stakes contests. A winner might typically receive a sweet as a prize. Playing for kisses or other favors from attending courtesans (hetairai, as they were called) was also a possibility. Vases portraying kottabos reveal that women played the game as hetairai, too.But eroticism didn’t just stop at prizes. It was customary to dedicate one’s throw to a lover, with the implication that success at kottabos augured success in one’s love life. Others didn’t mince words. In one poem, Cratinus recalls a hetaira dedicating her shot to the Corinthian male organ: “It would kill her to drink wine with water in it. Instead she drinks down two pitchers of strong stuff, mixed one-to-one, and she calls out his name and tosses her wine lees from her ankule [kylix] in honor of the Corinthian dick.”

Recreating Kottabos

Heather Sharpe, an associate professor of art history at West Chester University of Pennsylvania, has studied the game and even attempted to replicate it with her students. “To achieve the best results in kottabos, the participants had to loop a finger through one handle of the kylix and toss the juice overhand, as if they were pitching a baseball. Sharpe said that playing the game proved to be challenging, but she was amazed that some of her students started to hit the target within 10 to 15 minutes. “It took a fair amount of control to actually direct the wine dregs, and interestingly enough, some of the women were the first to get it,” Sharpe told Live Science. “In some respects, they relied a little bit more on finesse, whereas some of the guys were trying to throw it too hard.”

Dr. Sharpe and her students used diluted grape juice rather than wine. “Within about half an hour there was diluted grape juice everywhere, which made me realize it must have gotten pretty messy,” she says. “You’re aiming at the target, but the funny thing is these symposia were typically held in a more-or-less square room, and you had participants on 3 ½ sides. So if you missed the target it wouldn’t have been surprising if you hit someone across the room.”

The recreation also proved that the temptation to take a shot at a rival across the room must have been strong. In fact, in Aeschylus’s play Ostologoi (The Bone Collectors), Odysseus describes how during a game of kottabos, Eurymachus, one of Penelope’s suitors, repeatedly aimed his wine at Odysseus’s head, rather than at the plastinx, to humiliate him. And it seems that players took the game seriously, too, in spite of their casual reclining poses. “It’s funny because they did seem to be pretty competitive about this,” says Dr. Sharpe. “The Greeks, in a strange way, loved competing against each other, whether in the symposium or out in the gymnasium.”

Children’s Games in Ancient Greece

Among the children’s games, in particular the game of ball, which we find even in Homeric times, and it was very popular throughout the whole of antiquity, especially in the hours of recreation after the bath or after physical exercises in the gymnasium, and it was especially recommended by physicians as healthy exercise. Some other games also bore a semi-gymnastic character, and will therefore be mentioned afterwards under the heading of gymnastics.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Games of skill or chance, which were played with boards, figures, dice, etc., were very popular. We meet with these board games, which were already known to the Egyptians, even in the Homeric period. In later times, too, they were a favorite amusement, and we often find them represented on ancient monuments.

Among the various modes of playing these, some bore a great resemblance to our modern games; the “game of towns” may be compared to our draughts; two opponents played at a board divided into squares with thirty stones apiece, which differed in colour, and the game was, by enclosing a hostile stone, either to capture it or to prevent it from moving. The terra-cotta group represented here probably shows a game of this kind. A youth and a woman are playing together, while a third person, a caricature, is looking on; the board is roughly divided into forty-two squares, and there are twelve flat stones, but we cannot from this draw any conclusion about the nature of the game.

Toys in Ancient Greece

Toy horse from the 10th century BC Excavated toys and include push carts, terra cotta tops, marbles, knucklebones, ivory counters, ivory dolls, dancing dolls with movable arms and castanets. Archaeologists have also found dice with the same number configurations as modern dice and a baby feeder inscribed with words "drink, don't drop." Monkeys and dogs were kept as pets, and a few lucky children even got to have pet cheetahs. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

Among the toys at the "Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from The Classical Past” exhibit were baby dolls and baby rattles in the shape of pigs. Kids seem to have been particularly fond of knuckbones made from the ankles of sheep and goats, They threw them like dice and carried them around in little pouch, John Oakley, a classics professor at the College of William and Mary told U.S. News and World Report, “they’re all over the place.” Girls were encouraged to juggle to improve their motor skills.

The word "marble" comes from the Greek “marmaros” , which means polished white agate. Marbles made from polished jasper and agate, dated at 1435 B.C., have been found in Crete. Yo yos are also believed to have been used in ancient Greece where they were made from wood, metal and terra cotta.

Children in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome made hoops from dried and stripped grapevines and rolled them down the street with a rod. Rattles made with dried gourds filled with clay balls or pebbles were discovered in children's tombs dated at 1360 B.C. They were shaped like birds, pigs and bears. Rattles were also used in ancient rituals to scare off evil spirits. The earliest dolls were images and idols of gods. Playing with idols was considered sacrilegious so the first true dolls were model or ordinary people played with by children. Early females dolls had breasts and male dolls had penises.

Greeks and Romans had dolls with human hair and movable limbs that joined to hip, shoulder and knee sockets with pins. Most Greek dolls were females. The few male Roman dolls that have been found were mostly male soldiers fashioned from wax and clay. By the Christian era infant dolls were popular and children dressed painted dolls in miniature clothes and placed them in doll houses.

Party Games in Ancient Greece

On a higher level were those social entertainments which laid the intelligence and wit of the participants under contribution. To begin with, there was free conversation, dealing with the many questions of the day, politics, literature, etc.; but they generally avoided serious subjects, and Anacreon says:

“That man hold I not dear, who drinking his wine from a full bowl,

Ever of conquest and war sings but the dolorous strain,

But who the glorious gifts of the Muses and fair Aphrodite,

Mingling together, recalls feelings of joy and of love.”

They amused themselves with games requiring thought — riddles and such-like — as, for instance, naming an object which contained a certain god’s name, or singing a verse in which one particular letter must not appear, or whose first and last syllables must have a particular meaning, etc. In circles where the culture was above the average, a definite subject was sometimes given the guests for oratorical discussion. Here, as in the drinking and singing, the turns also went to the right after the subject had been previously discussed and fixed by all together. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The appointed tasks were of various kinds. A favorite amusement seems to have been to compare the guests present with particular objects, such as mythical monsters, etc., and here opportunity was given for showing wit and making innocent jokes. Sometimes, when a professional “entertainer” was present, the task was left to him, but as he was not always plentifully supplied with wit, it often happened that the poor man, who practised his jokes from necessity, grew quite sad at the disregard of his witticisms.

A more difficult task, and one making greater demand on the intellect, was to make a little improvised speech on some set subject, to praise or blame some particular thing, and this became especially common with the development of the rhetorical art. Thus, in the “Banquet” of Xenophon, each guest has to say what he is proud of, and to give his reasons; in Plato’s symposium, the glorification of Eros is the task appointed. In the ages of the Alexandrine learning, this even led to learned discussions, in which scientific problems of all kinds were treated over the cups. Those who were successful in these intellectual contests, who solved difficult riddles, etc., were rewarded, receiving wreaths or fillets, or sometimes kisses; on the other hand, the symposiarch inflicted punishments on those who were unsuccessful, and these usually consisted in drinking, at a draught, a whole cupful of unmixed wine, or, which was worse, wine mixed with salt water.

Gambling in Ancient Greece

Dice were usually made of ivory or bone. Like modern dice the numbers were positioned so that the ones on opposite side always added up to seven: 1 and 6, 2 and 5 and 3 and 4. According to Sophocles the Greeks invented dice during the siege of Troy. Plato claimed that God invented dice and gave specific credit to the Egyptian deity Theuth. Herodotus attributed the invention of dice to the Lydians, who he said introduced them during a time of famine so the masses could keep themselves entertained on days they were not allowed to eat. Another story attributes the game to the Greek hero Palamedes to keep his soldiers from getting bored during the Trojan war. Dice, identical to ones in use today, were found in Egyptian tombs dating back to 2000 B.C.

The games played with knuckle-bones and dice were pure games of chance, and were very often played for money. In playing dice they used several, generally three, dice, corresponding exactly to those of the present day, and a cup from which they threw them, and a board or a table with a raised edge on to which they were thrown. The victory depended on the number of points thrown. The best throw, three times six, was called the “Coan,” the worst, three times one, was called the “dog,” but there were various rules of the game dealing with particular combinations, such as is still the case in dice-playing at the present day. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Another game of chance was “fast and loose,” which very closely resembled the game still played at fairs by sharpers. A strap was folded double and wound round several times on a table; the player then pricked it with a dagger or other pointed instrument, and if, when the strap was unwound, it appeared that the point had gone between the layers of the strap, he won; but he lost if the strap could be entirely wound off.

There were public houses and gaming houses, but these do not appear to have played a great part in the lives of the men. The drinking parties supplied sufficient opportunity for social meetings. Those who visited the public drinking bars usually did so for other purposes as well — to see pretty girls or to meet companions for dice, though both these purposes could be effected in special houses. It is natural, therefore, that it was not regarded as respectable to visit these wine taverns, and that grave men, as well as youths of good principle, avoided them. Still, even here the custom seems to have gradually relaxed, and though the Athenians were never as bad as the inhabitants of Byzantium. inhabitants of Byzantium, who were accused of spending the whole day at the bars, yet at the end of the fourth and in the third century B.C. it was very common for young men, or people of the lower classes, to dawdle about in the wine bars and gaming houses.

Cock and Quail Fighting in Ancient Greece

A popular amusement in Greece was cock and quail fighting, a pursuit which played so important a part at Athens that even the great theatre of Dionysus had to be used for the purpose, and the Athenians actually maintained that this was a spectacle calculated to rouse the courage of the citizens to brave deeds. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Fighting cocks were trained at Tanagra and Rhodes; both young and old men aimed at the possession of fighting cocks or quails, carried them about for hours, and tried by all possible means to excite their courage in order to obtain prizes. For this purpose they were fed with garlic, and sometimes brazen spurs were even tied on them in order to make the wounds they inflicted more serious. The representations show that before the beginning of the fight each owner took his bird in his hand, knelt down, and thus gradually approached the cocks to one another in order to excite them from a distance; then they were sent against each other, and the owners stood up again.

Sometimes the hens were present at the fight, because the cocks were more inclined to fight in their presence. A curious custom is mentioned — namely, that the owner of the defeated bird took it up as quickly as possible and shouted loud into its ear; the object of this was supposed to be to prevent the defeated cock from hearing the triumphant crow of his conqueror, and thus being discouraged for future combats.

Cockfighting predates Christ by at least 500 years. Believed to have originated in China or India, it was practiced by the ancient Greeks, Persians and Romans, who identified it with Eros, the God of Love and passed it on to medieval Europe.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024