Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT GREEK MEN’S CLOTHES

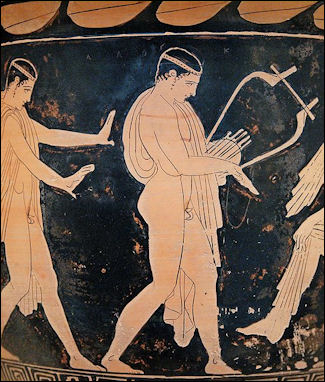

Greek, Macedonian and Roman men favored toga-like garments while ancient Chinese and Persian men often wore trousers. Greek men wore three kinds of clothing: 1) a chiton (See Below); 2) a himation, a cloak draped in various ways around the body with "varying degrees of modesty"; and 3) a claymys, a cloak draped around one shoulder and pinned to the other. Belts were sometimes worn and excess material was stuffed into a pouch.

Greek, Macedonian and Roman men favored toga-like garments while ancient Chinese and Persian men often wore trousers. Greek men wore three kinds of clothing: 1) a chiton (See Below); 2) a himation, a cloak draped in various ways around the body with "varying degrees of modesty"; and 3) a claymys, a cloak draped around one shoulder and pinned to the other. Belts were sometimes worn and excess material was stuffed into a pouch.

Men, from the time of the Homeric poems downwards, wore a “chiton,” rectangular in shape and somewhat wider than the body, closed on the sides and across the top except for openings left for the head and arms. A short woolen chiton was the usual dress for soldiers, workmen, and poor persons, while the nobles of the Homeric poems seem to have worn linen chitons reaching to the feet. Over this a wrap, either rectangular or curved on one side, was arranged in various ways. The earliest representations show men wearing a wrap with one curved edge, and apparently doubled like a shawl.[Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Men in ancient Greece customarily wore a chiton similar to the one worn by women, but knee-length or shorter. An exomis, a short chiton fastened on the left shoulder, was worn for exercise, horse riding, or hard labor. The cloak (himation) worn by both women and men was essentially a rectangular piece of heavy fabric, either woolen or linen. It was draped diagonally over one shoulder or symmetrically over both shoulders, like a stole. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Ancient Greek Dress", Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org]

Young men often wore a short cloak (chlamys) for riding. The chlamys was a seamless rectangle of woolen material worn by men for military or hunting purposes. It was worn as a cloak and fastened at the right shoulder with a brooch or button. The chlamys was typical Greek military attire from the 5th to the 3rd century BC.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Costumes of the Greeks and Romans” by Thomas Hope (1962) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek, Roman & Byzantine Costume” by Mary G. Houston (2011)

Amazon.com;

“Women's Dress in the Ancient Greek World” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2023) Amazon.com;

“Dress in Mediterranean Antiquity: Greeks, Romans, Jews, Christians” by Alicia J. Batten, Kelly Olson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Garments: Textiles in Greek Sanctuaries in the 7th to the 1st Centuries BC” by Cecilie Brøns (2017) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece” by Mireille M. Lee (2015) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z” by Liza Cleland, Glenys Davies, et al. (2007) Amazon.com;

“History of Costume: From the Ancient Mesopotamians to the Twentieth Century” by Blanche, Payne (1997). Amazon.com;

“How the Greeks and Romans Made Cloth” (Cambridge School Classics Project)

Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Uniform Dress of Spartan Men

According to Thucydides, it was at Sparta that it first became customary to adopt a uniform dress for the whole male population, and thus to do away with a distinction which had hitherto prevailed between the dress of poor and rich. This distinction, at any rate, held in so far that at Athens the richer people, as Thucydides states, wore the long linen chiton, the poorer people the short woollen one. At Athens and in Ionia the long linen chiton remained as the dress of older people till shortly before the time of Thucydides; but then it was universally discarded, or rather reserved for the classes mentioned above, and for festive occasions; while the short woollen chiton from that period became the universal dress. This is usually found in the form of a widish garment sewn together below the girdle, and above it divided into two parts, a front and back piece, put on in such a manner as to be fastened together by pins or fibulae on the shoulder. If the chiton was allowed to fall quite free it usually fell down about as far as the knees; but it was customary, especially when unimpeded and free movement was necessary, to draw up a part above the girdle and let it fall in folds below it. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Workmen, countrymen, sailors, and others whose occupation required free movement of the right arm, used only to fasten the two pieces of the chiton on the left shoulder, then the points of the other side hung down in front and behind, and left the right breast, shoulder, and arm exposed. This costume, of which a relief gives a representation, was called exomis. Strictly speaking, it is no actual garment, but only a particular way of wearing the chiton; but special tunics for labourers were made in this fashion. Besides this, chitons were afterwards made with the upper part also sewn together, and with armholes or short sleeves, which, however, never covered more than a part of the upper arm. Long sleeves falling to the hand belong exclusively to barbarian costume. Yet the bib, which as late as the first half of the fifth century was worn with the male chiton also, is not a part of later costume.

From this time onward the name “himation” was used for the cloak worn with the chiton, while “chlaina” was only retained for a special kind, distinct rather by its material than by its shape. The himation was often worn in the oldest period in the way described above, that is, with two points falling on the two sides in front. But it became more and more common, and from the classic period onwards quite universal, to fold the cloak tightly round, and this was done as follows. One point was drawn from the back over the left shoulder and held fast here between the chest and arm, then the cloak was drawn round over the back in wide folds reaching to the shins, and from there back again to the front on the right side. This was done in two ways. If the right arm was to be kept free the himation was drawn through under the right shoulder and in front folded across the body and chest, while the last piece was thrown back across the left shoulder, or else over the left arm.

The other mode, and the one common in the dress of an ordinary citizen, was to draw the cloak over the right arm and shoulder, so that at most the right hand was exposed, and then to throw it back again over the left shoulder. This arrangement was facilitated by small weights of clay or lead sewn on the points, which helped to keep the cloak firm in its place. It was, however, a special art, which required practice, and probably also assistance, to produce a beautiful and harmonious drapery in this kind of dress; and the position of the wearer showed itself in the way in which he wore his himation, which ought neither to be drawn up too far, nor fall too low. It was also regarded as inelegant to wear the cloak from right to left. There is no nobler or more perfect example of this costume, in which the chiton is combined with the himation, than the portrait statue of Sophocles in the Lateran. Here the wide cloak with its many folds covers the form in such a way as not to hide the shape of the body, and the various folds caused by the position of the arm and the mode of draping the cloak are combined together in the most harmonious manner. A humorous counterpart of this ideal figure in terra-cotta, representing a vulgar citizen in chiton and himation.

Men’s Chiton

As regards the chiton of the oldest period, we infer, from allusions in epic poetry, with which the oldest monuments agree (for the discoveries at Mycenae give us no distinct notion of pre-Homeric costume), that both the short and the long kinds were in use. The short chiton seems to be the usual dress of daily life; it was especially worn when free movement was required, and was therefore the suitable garment for war or hunting, for gymnastic exercises or manual labour. The long chiton, which was afterwards regarded as especially Ionic, and certainly maintained itself longer in Ionia and in Attica than in the rest of Greece, was not, however, unknown to the Doric people. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

It was the usual dress for men of advanced age and good position; it was also worn by young people on festive occasions. We therefore find on the monuments of the oldest style that not only the older gods wear a long chiton, but also that young men are clothed in it on{ festive occasions, or if they are in any way connected with religious functions, as, for instance, priests, harp-players, flute-players, charioteers, etc. This use of the long chiton remains up to the classic period. Thus, for instance, we see the figure known as the Archon Basileus in the central group of the Eastern Parthenon frieze in this dress; and tragic actors, if they represented men of good position and in peaceful circumstances, also continued to wear the long chiton.

Epic poetry itself gives us no direct information about the shape of the chiton in the Homeric period, Wolfgang Helbig (1839–1915), a German classical archaeologist, maintains, basing his assertions on some casual indications, and chiefly on the oldest monuments, that it differed from the dress of the classic period in being close-fitting and free from folds. It is true that the old vase paintings show us the short chiton fitting closely round the body and drawn quite firmly round the legs. It is girt fast round the hips, and as a rule does not go below the knee. However, it is not safe to draw conclusions of this kind from ancient pictures, for much which might be regarded as characteristic of ancient costume may be due only to the incompleteness of art, which was not yet capable of representing full garments with folds.

Thus, in ancient works of art, the long chiton also appears quite narrow in the upper part, but then falls perpendicularly from the waist, sometimes gradually, but more often straight without any folds to the feet. Both the long and short chitons as a rule have no sleeves, but only an armhole; we sometimes find short sleeves not quite covering the upper arm. Unfortunately, we cannot form a clear notion from the pictures of the mode in which it was put on. It is, however, probable that the short chiton was sewn together all round and thrown over the head, where there may have been an additional slit connected with this opening, and fastened with a pin. There are, however, no traces of this on the monuments, nor are fibulae or brooches mentioned in the Homeric descriptions in connection with the male chiton. Probably the long chiton was cut in the manner of a chemise. Helbig’s hypothesis that there was a slit down the middle of the front is just as uncertain as his similar assumption with regard to Homeric female dress.

Besides the chiton, the older male costume also had a sort of loincloth or apron. It is not at all improbable that at one period the Greeks wore merely the apron and cloak, and no chiton. When the latter became universally fashionable (which, according to recent surmises, was due to Semitic influence) the cloth disappeared, or continued only as part of military dress.

Men’s Himation

The himation, or chlaina, appears on ancient monuments stiff and free from folds, like the chiton. This is a garment resembling a mantle, which appears in many archaic vase pictures in two distinct forms: either as a wide cloak covering the greater part of the body, or as a narrow covering lightly draped. The first form, corresponding to the later male himation, is most commonly combined with the long chiton. The cut of this cloak is four-cornered, probably oblong, and it is worn in such a way that the greater part of it falls behind and covers the back and part of the legs, while in front it is thrown over the shoulders and arms, and falls down over the body, two of its points falling within the arms and the other two without. The other form, which may be in general compared with the later chlamys, is found with both the long and the short chiton, and is also sometimes worn as the only covering, without any under garment. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

This may, however, be regarded as the ideal clothing, which does not correspond to real life, just as in later monuments we find the chlamys alone without the chiton. It is put on in such a way that the lower arm is left uncovered, and the two points fall down in front over the shoulder and upper arm, while behind it either covers only the upper part of the back, or else the cloak falls down so far that its edge is almost as low as the points in front. We cannot pronounce with certainty on the shape of this cloak. It appears, however, to have been oval or elliptical, and to have ended in two points; it was folded in such a way that the folded part was worn inside, while the edges, which were ornamented with wide borders, fell outside. Where the shape of the cloak is that of an ellipse cut through the long axis, the folding is also evident. I should therefore differ from Helbig in regarding this narrower{ chlaina as the garment called in epic poetry diplax. Neither kind of cloak is fastened, and they both differ from that of later periods in being worn open in front. In Homeric poetry another kind of chlaina is also mentioned, which corresponds more closely to the later one; since it is stated that the folded chlaina is fastened on the shoulder with a brooch. No proof of this, however, has as yet been found in the older monuments.

As a remnant of the most primitive dress, clothes made of skins, such as were afterwards worn only by country people, huntsmen and the like, still existed in the Homeric age. Homer several times mentions skins as the dress of soldiers; on the older monuments we see them drawn over a short chiton, and sometimes even fastened with a girdle. How long this ancient dress continued in use we cannot determine with any certainty; but the majority even of vase pictures with black figures show a different dress. It is true, as we mentioned just now, that the long chiton still continued in use besides the short one, but the cut and the mode of wearing it changed.

Chlamys

The “chlamys” was a special kind of cloak which originated in Thessaly, but from the fifth century onwards became common in Greece. Originally it was a soldier’s or rider’s dress, and is, therefore, only seen on statues worn over armour. It is a short cloak of light material and oval shape, fastened by means of a brooch either in front at the neck, or more commonly on the right shoulder, thus covering the left arm and leaving the right free. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The chlamys was the common dress of youths as soon as they attained their majority and entered the cavalry; till that age they wore no upper garment over the chiton in the ancient period, but in later times a wide himation, in which they usually enveloped themselves entirely. It was regarded as correct for modest boys not to have their arms exposed. Hermes also, the divine representative of youth, usually appears in the chlamys, but this is generally lightly folded and thrown over the left arm. Apollo too, except where he wears the long chiton as harp-player, is usually represented on works of art with the chlamys. It is, however, unusual in male dress, with the exception of military costume, and is never found in combination with the long chiton.

At home, as a rule, only the chiton was worn. It was, however, not considered correct to be seen thus in the street: only artisans or eccentric people went out without a cloak; but it was just as incorrect to appear without the chiton, only in the himation or chlamys. It is true this is very common on works of art: Zeus, Poseidon, and some other gods are represented without the chiton, and only in the himation, and Hermes and Apollo only in the chlamys; and even in representations of daily life we very often see in statues, reliefs, vase pictures, etc., men without under garments, clad only in the cloak, and also in portrait figures. This is, however, a liberty taken by artists in order to avoid concealing the body entirely by the dress, but by no means corresponding to reality. Only those who specially desired to harden their bodies, and also poor people and certain philosophers who wished to proclaim their cynic principles by exceedingly scanty dress, went out, even in winter, in a cloak without an under garment. Shirt and trousers were unknown in Greek male dress; the latter are Asian, and therefore only appear on monuments representing barbarous persons.

Men’s Hats and Head Covering in Ancient Greece

As a rule, men went bare-headed, or wore caps in bad weather. Generally speaking, they distinguished, as we do, between hats and caps. The hat, whose distinguishing mark was the brim, bore the name petasos. It originated in Thessaly, but spread to other places, and at Athens was regarded as the characteristic riding hat, and as such was worn with the chlamys by youths. We see many in this dress on the Parthenon frieze. Otherwise the petasos was essentially a part of travelling dress, and, therefore, a usual attribute of Hermes as messenger of the gods. When older men wore the petasos there was generally some distinct reason for it. The shapes of the petasos on works of art are so various that it is sometimes difficult to tell whether they ought all to be included under the same name. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Some of the hats are so very like caps that we can scarcely decide whether they ought to bear the name of petasos. In the oldest period the petasos almost always had a pointed, rather high crown, and a broad brim turned up in front and behind. Afterwards varieties were introduced; sometimes the crown was semi-circular, sometimes flattened, now high, now low, or with a little point like a button; the brim, too, was sometimes broad, shading the whole face, sometimes quite narrow; now turned down, now horizontal; at other times, again, turned up or bent round the head. Thus in the first half of the fifth century, we find a very peculiar shape. The brim projects in front in a narrow point, and at the back is turned up as far as the high conical crown. The commonest shape is that the crown is tolerably flat, generally not higher than the skull; the brim, which is rather broad, and generally turned down, is not circular all round, but cut out at several places — either between the ears and the forehead, so that a point falls over the latter, while the brim extends in semi-circular form round the back of the head; or else this half is cut out in the same way as the front part, so that the brim ends in four points, which generally fall over the forehead, back of the head, and ears. Still, we sometimes find instances where it is only cut out over the forehead, and the points fall to the right and left of the face. This shape is very common in the best period, that is, in the fifth and fourth centuries. Afterwards, there were some very strange shapes, ich is found on vase pictures of the best period and reminds us of the hats pointed in front and behind worn at the beginning of this century. The petasos was fastened under the chin with a cord; when it was not wanted it was pushed down below the neck, where it was kept in place by the cord; and we find it frequently in this position.

When, as sometimes happens, the petasos has a high crown, and a narrow turned-up brim, it is often very like the pilos, a cap of leather or felt, which was the common dress of workmen, especially smiths, countrymen, fishermen, sailors, etc. Odysseus, as sailor, is almost always represented with it; and so is Charon, the ferryman of the nether world, Hephaestus, as smith, etc. Invalids who were obliged to protect their heads from the weather, also wore such caps. These caps, too, were of various shapes; semi-circular, fitting closely to the head, and half-oval, projecting somewhat beyond the head, or of a more pointed conical shape. It is evident from the drawing that the material must have been skin, which was the commonest next to felt. These caps were often fastened with strings below the chin, and there was sometimes a bow at the apex by which they could be hung up.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024