Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex) / Economics

ANCIENT GREEK CLOTHES-MAKING

woman spinning cloth Clothes-making appears to have been a major household chore or duty in ancient Greece. For women at home, not only had all the food to be prepared for the household, but also the clothing had to be provided for all its members; for it was very unusual for women, especially those who had slaves at their disposal, to purchase stuffs or clothes ready-made. Such women therefore spent a great part of the day with their daughters and maids in a specially appointed part of the house, where the looms were set up. Here, in the first place, the wool, which was bought in a rough condition, was prepared for working, by washing and beating, then fulled and carded, disagreeable occupations which, on account of the exertion required, were usually left to the maids. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

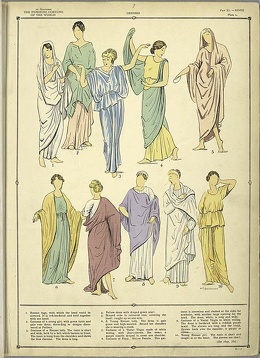

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In antiquity, clothing was usually homemade and the same piece of homespun fabric could serve as a garment, shroud, or blanket. Greek vase painting and traces of paint on ancient sculptures indicate that fabrics were brightly colored and generally decorated with elaborate designs. Clothing for both women and men consisted of two main garments—a tunic (either a peplos or chiton) and a cloak (himation).” [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Ancient Greek Dress", Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org]

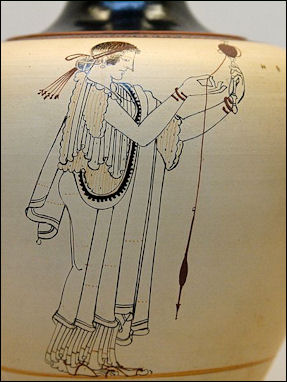

Cloth was woven in the size desired for a particular garment, so that no cutting was necessary and consequently there were no edges to hem. Sewing was therefore restricted to seams, of which few were required, but a great deal of time and skill could be devoted to embroidered ornament upon fine garments. The earlier fashion, seen on black-figured vases, was to cover the cloth with patterns, but later only borders were used, or bands of figures. On an oinochoë of the fifth century are two ladies perfuming clothes. The garments and head-dresses they are wearing and the clothes they are folding are worked with beautiful borders in the wave pattern and ornaments in the form of conventionalized flowers. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Besides providing fine apparel for themselves and their families, women also expended their skill on garments which they offered to the goddesses: the treasuries of Athena and of Artemis at Athens contained chests full of many-colored robes offered by worshippers. Naturally in the course of time various industries sprang up which contributed manufactured products to the household, but spinning and weaving continued to be domestic occupations, at least to provide clothing for the slaves.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“How the Greeks and Romans Made Cloth” (Cambridge School Classics Project)

Amazon.com;

“Ancient And Medieval Dyes” by William Ferguson (2012) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“Spinning Fates and the Song of the Loom: The Use of Textiles, Clothing and Cloth Production as Metaphor, Symbol and Narrative Device in Greek and Latin Literature” by Giovanni Fanfani, Mary Harlow, et al. (2016) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean” by E.J.W. Barber (1992) Amazon.com;

“Fabric of Civilization” by Virginia Postrel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History” by Kassia St. Clair (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Tools, Textiles and Contexts: Investigating Textile Production in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age” by Eva Andersson Strand and Marie-Louise Nosch (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Textiles: Production, Crafts and Society” by Marie-Louise Nosch, C. Gillis (2007) Amazon.com;

“First Textiles: The Beginnings of Textile Production in Europe and the Mediterranean” by Małgorzata Siennicka, Lorenz Rahmstorf, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Competition of Fibres: Early Textile Production in Western Asia, Southeast and Central Europe (10,000–500 BC)” by Dr. Wolfram Schier and Prof. Dr Susan Pollock (2020) Amazon.com;

Materials Used in Ancient Greek Clothing

Most cloth was made from wool and linen. Much of it was rather course. Very few remnants of Greek cloth remain. Most of what we know comes from written records, sculptures, bas-reliefs and vase paintings. Penelope's loom was a major feature of the “ Odyssey”. Homer refers to "fair purple blankets" and "thick mantels.”

The Greeks and Romans used leather and developed fairly sophisticated methods of tanning. Roman soldiers wore breastplates of felt and armies traveled with sheep and looms to clothed their soldiers. Instead of mothballs Romans used bare breasted virgins to fight off wool eating moths.

As a rule, ancient Greeks wore, as we do, lighter stuffs in the summer and heavier ones in the winter; but though we very often find on archaic monuments transparent garments showing distinctly the outline of the body, we are scarcely justified in assuming a very widespread use of really transparent garments. Even though such thin materials may have been worn at that time, especially by hetaerae, their extensive use in vase painting is probably due to the fact that the painters, not knowing how to represent the outline of the body and the movements of the limbs under the dress, and yet desiring not to hide them completely by the clothes, resorted to this expedient of letting the outline appear through the dress material.

These thin stuffs were always common in the dress of the hetaerae, but respectable women used them only as under garments. We may, however, assume that this was also a matter of fashion, since materials from the looms of the island of Amorgos, which were especially noted for their fineness and transparency, were only fashionable for a short time in the period of the older Attic comedy. Later allusions to these stuffs are made chiefly by the learned, and do not refer to actual reality. Moreover, it is natural that the circumstances of the persons concerned played a part in the choice of coarser or finer materials. The stuffs introduced from foreign parts, such as cotton and muslin, could only be worn by the rich, as also silk, which, even in the Alexandrine period, was very rare and expensive. On the other hand, common men wore felt-like materials, and countrymen even tunics of skin or leather.

Ancient Greek Fabrics

On this lekythos attributed to the Amasis painter, women are shown folding cloth, spinning wool into yarn

Herodotus described the introduction of linen, but woollen materials were not on that account discarded; and as men ceased to wear the chiton long, it became commoner to make it of wool. The oldest sculpture as a rule represents two distinct materials when once we get beyond the tight-fitting costume of the earliest period. One of these shows fine and flat folds, while the other falls in large, deep folds. We cannot always maintain with certainty that these are two distinct materials, the former wool, the latter linen; sometimes it seems as though there were only two qualities of the same material, one being fine and thin, and the other coarse and thick. Yet the frequent use of linen is proved by the regular parallel and zigzag folds so common in the older art, which could only be produced in linen by artificial means. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The Romans and Greeks were familiar with silk, but they had no idea how it was made. Pliny the Elder speculated the textile was made from "the hair of the sea-sheep" and Aristotle described the silkworm as a horned worm the size of a cat. Alexander the Great brought silk back with him after his conquest of Persia, and the fabric was all the rage in ancient Rome, where laws were passed to curb demand for the cloth.╟

As the fashion in dress changed, so did the use of materials with patterns; for garments worn at religious ceremonies, or by actors, the coloured embroidery was retained; but in ordinary life the men, and even women, gradually discarded it, or at any rate reduced it to moderate proportions compared with the rich fullness of ornament in the older fashion, which almost concealed the real colour of the dress. This is especially noticeable in the chiton when it falls in free folds, while the old-fashioned chiton, which had very few folds, bore bolder designs. It is also the case with the himation, which even in the classic period, when it no longer fell stiff and straight over the back, but was drawn round the body in plentiful drapery, was often richly adorned with embroidery. The reason is probably because such shawl-like garments are more loosely related to the body, and therefore the introduction of a pattern which weakened the impression of the figure is less disturbing here than in the chiton. However, these bright-coloured cloaks were exceptional luxuries. The fashion of the better period shows its classic sense of beauty in forming chiton and cloak from materials of one colour, and merely introducing ornaments at the seams and edges, and these such as are of especial beauty and noble simplicity.

Ancient Greek Dyes and Colored Fabrics

The Greeks imported from purple cloth from Tyre, embroideries from Sidon and fine linen from Egypt. Silk from China and fine muslins from India began making their way to the wealthy with some regularity after Alexander's conquests. Blue India dye is derived from a blue powder extracted from the “ indigofera” plant. The dye was known to the Greeks and Romans and used by Egyptians to dye mummy cases. The Greeks used brown, red and yellow dyes made from plants, bark and minerals. Many of their garments were bleached white and adorned with hand applied designs with geometric patterns.

Otherwise, we know very little about the colour and pattern of the dresses. The clothing worn by men, or, at any rate, those of the lower classes who laboured in the workshop or in the field, was certainly dark, either of the natural colour of the wool or dyed brown, grey, etc. Otherwise the commonest colour for the chiton and himation was white, and, as such garments naturally soon got dirty, they were often sent to the fuller, who washed them and gave them fresh brightness by means of pipeclay and similar methods. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

On festive occasions gaily-coloured dresses were usually worn, and then even simple people indulged in the luxury of bright colour; though, as a rule, to display this in ordinary, every-day life was regarded in the better ages of Greek antiquity as a mark of vanity or characteristic of a dandy. Perhaps, women were more inclined to bright hues, and they were especially fond of saffron-coloured dresses, and also of materials with coloured borders and rich designs. Generally speaking, we may infer from the works of art that bright colour and rich ornamentation were most popular in the oldest period, and afterwards again in the epoch of declining taste; while the classic period made but a sparing use of either. The older vase pictures almost always represent materials with coloured patterns, either purely ornamental designs , or with representations of figures. Sometimes whole scenes full of figures in coloured embroidery were part of the dress, and this was sometimes arranged in rows, like the decorations on pots in ancient art. This is quite natural if we consider that in the more ancient costume there was scarcely any drapery; both the chiton and the cloak were drawn tightly round the figure, and, therefore, the pictures could be fully developed and seen without any interruption from folds. Purely ornamental patterns are also very common, and show great variety, but very seldom good designs. Checks and diamonds were especially popular. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Phoenician Purple Dye

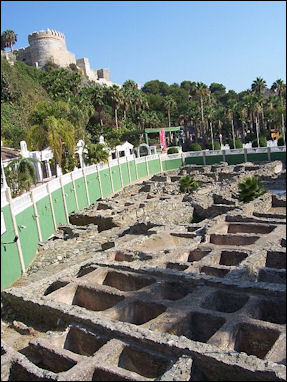

Vestiges of purple dye

industry in Lebanon Purple was greatly prized among the Greeks and in the ancient Mediterranean world and Europe. The Phoenician City of Tyre grew rich from the sale of a purple-dyed textiles that were used to denote royalty. The dye was produced from murex, a trumpet-shaped marine snail still found among rocks in the eastern Mediterranean today. Piles of the shells and large vats indicated that dye production was carried out on an industrial scale. In Sidon, archeologist found a 300-foot-long mound of murex shells.

According to legend purple was discovered by the Phoenician god Melkarth, whose dog bit into a seashell, resulting in his mouth becoming a rich shade of purple. Other have said the dye was discovered by noting that people who ate the snail had purple lips.

Royal purple was produced as early as 1200 B.C. The dye was made of urine, sea water and ink from the bladders of the murex snails. To extract the snails, the shells were put in a vat where their putrifying bodies excreted a yellowish liquid. Depending on how much water was added the liquid produced hues ranging from rose to dark purple.

"Born to the purple" became a common expression to describe royalty. Purple cloth was treasured by the Greeks and Romans and remained extremely valuable through Byzantine times. One gram of pure purple die was worth 10 to 20 times its weight in gold. Some of the richest people in ancient Phoenician were purple dye merchants.

Purple is no longer made from sea shells in the eastern Mediterranean but it is still is done in Oaxaca, Mexico. In the winter “ Purpura” mollusks are collected from rocks and opened and the purple dye is applied to yarn right there in the spot.

See Separate Article: PHOENICIAN TRADE: COLONIES, PURPLE DYE, AND MINES factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Clothing Designs and Decorations

Harold Koda of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Most early postclassical depictions of ancient Greek themes represent the gods, demi-gods, and mortals in loosely draped, monochromatic robes. If present at all, the only ornamentation is a narrow banded border of braid or embroidery. However, pottery, painted sculpture, and the written word have given us extensive evidence of the use of decorative embellishments in ancient Greek dress. A cursory survey of red- and black-figure vase paintings alone reveals that antique dress was composed of a rich variety of graphically patterned textiles.” Also, “there has been a longstanding assumption that ancient Grecian styles were achromatic. This misconception, thought to derive from the faded and abraded surfaces of originally polychromed Greek statuary and architecture, continues to this day in fashion. [Source: Harold Koda, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Among the most common designs seen in ancient art is the Greek-key pattern, a rectilinear meander. Other abstracted forms of wave patterns, geometric repeats, and palmette friezes are also seen on classical garments, as are more intricate borders depicting themes ranging from animals, birds, and fish to complex battle scenes. Nevertheless, such patterns have rarely been used by later artists or by contemporary designers. Of all these motifs, the Greek key and wave meander appear most frequently in designs intended to evoke the antique. In some instances, the key pattern is broken into a discontinuous segmented band, but even this disrupted linear repeat is sufficient to sustain the classical connection. \^/

“Although well represented in art, the use of mythological attributes to designate an Olympian deity is less common in fashion. However, the ancient Greek practice of recognizing achievement and bestowing honor through the presentation of a coronet of flowers and leaves has been adumbrated in Neoclassical embroideries and in the more recent work of a number of designers. The materials comprising the coronets originally associated with the presiding deities—laurels for Apollo, olive leaves for Athena, roses for Aphrodite, ivy for Dionysos —were perhaps too esoteric for the purposes of fashion and have generally been obscured. But other mythic attributes have continued with their original meanings intact.” \^/

Ancient Greek Clothmaking

Most cloth was made with relatively simple warp-weighted looms. Women and slaves made cloth at home or bought it in shops, worked by freed slaves or artisans, who used specialized in one process — cleaning and carding, fulling, spinning, dyeing or weaving. The fulling of the woven materials was not undertaken at home, since it was a difficult operation and required special arrangements; it was done by the fuller, to whom any soiled cloth garments were also sent.

The methods used to make wool and cloth in ancient Greece lived on for centuries. After a sheep was sheared, the wool was placed on a spike called a distaff. A strand of wool was then pulled off; a weight known as whorl was attached to it; and the strand was twisted into a thread by spinning with it the thumb and forefinger. Since each thread was made this way, you can how time consuming it must have been to make a piece of cloth or a sail for a ship.||

The home in ancient times, especially the country house, was a manufactory on a small scale, like many American homes of a century ago. Most of the clothing for the family was made there, and consequently the mistress of the house must understand wool-working in every stage and the making of linen cloth, and must also be able to teach and direct the slave women. Wool was often bought in the raw state or even in the fleece, which necessitated cleansing it, certainly a disagreeable task. The Syracusan lady in the Fifteenth Idyll of Theokritos scolds because her husband has bought five dirty fleeces of poor quality — “work upon work” for her. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

For making the roves a pottery shield, called epinetron or onos, was placed on the knee and the fibers rubbed over it. An interesting example, decorated with drawings of women at work, has the upper surface covered with a scale pattern which furnished the slightly roughened surface necessary for making the roves. The covering, however, was sometimes dispensed with; a finely decorated toilet-box has on one side a drawing of a woman carding over her bare knee. This box also shows the next stage in the making of cloth, the spinning, for which distaff and spindle were used. A small weight, the spindle-whorl, usually of terracotta, was attached to the thread below the spindle to increase the twisting motion.

Ancient Greek Weaving

It is believed that women spent most of their time weaving. Wool was the most common fiber available and flax was also widely used. Cotton was stuffed into the saddles of Alexander the Great's cavalry in India to relieve soreness but that was largely the extent of its introduction to Greece.| [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

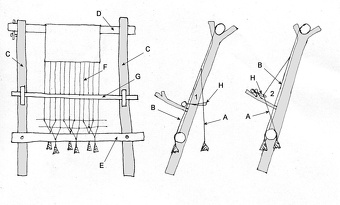

To make cloth, threads were placed on a warp-weighted loom (similar to ones used by Lapp weavers until the 1950's). Warps are the downward hanging threads on a loom, and they were set up so that every other thread faced forward and the others were in the back. A weft (horizontal thread) was then taken in between the forward and backward row of warps. Before the weft was threaded through in the other direction, the position of the warps was changed with something called a heddle rod. This simple tool reversed the warps so that the row in the front was now in the rear, and visa versa. In this way the threads were woven in a cross stitch manner that held them together and created cloth. The cloth in turn was used to make cushions, upholstery for wooden furniture and wall hangings as well as garments and sails.||

Using an Ancient Greek Loom

A warp-weighted loom has two upright posts (C); they support a horizontal beam (D), which is cylindrical so that the finished cloth can be rolled around it, allowing the loom to be used to weave a piece of cloth taller than the loom, and preserving an ergonomic working height; The warp threads (F, and A and B) hang from the beam and rest against the shed rod (E); The heddle-bar (G) is tied to some of the warp threads (A, but not B), using loops of string called leashes (H); So when the heddle rod is pulled out and placed in the forked sticks protruding from the posts (not lettered, no technical term given in citation), the shed (1) is replaced by the counter-shed (2); By passing the weft through the shed and the counter-shed, alternately, cloth is woven

The loom used in Greece and Italy was upright, consisting of two posts with a cross-bar. The threads of the warp, alternately long and short, were held by terracotta weights tied to the lower ends. A loom-weight from Crete is marked with the owner’s name, Kaleneika, wife or daughter of Teriphos. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

The wool thus prepared for working was then put in large work-or spinning-baskets, and we often see these on monuments which represent scenes from a woman’s life. A statue of Penelope, the prototype of an industrious woman, of which several replicas have come down to us, represents a spinning-basket under her chair. The spinning-wheel was unknown to antiquity, but the distaff and spindle were used exactly as they still are in the south. The woman here represented is seated (sometimes we find women walking or standing as they spin); she holds up the distaff in her left hand; in front of her is a stand, on which wool or flax seems to be fastened ready to fill the distaff afresh. For weaving they used an upright loom of tolerably simple construction, but yet suited for weaving heavy materials and elaborate patterns. From a vase picture of Penelope at the loom. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We can recognise on the already finished material, an ornamental border and various figured patterns interwoven. The construction of the loom is only superficially indicated, and has therefore been explained in many different ways, into which we cannot at present enter. One vase painting represents a number of women, of whom some are occupied with feminine work and others with their toilet. On the left we see a woman holding a spinning-basket in her left hand; further to the right a second woman is seated on an easy chair, holding an embroidery frame, on which a piece of material is stretched, while a third woman stands near, watching her. Further to the right is a fourth, who is drawing up the folds of her dress, and probably about to fasten her girdle. The woman sitting next her on the easy chair holds an object in front of her which is not quite distinct — possibly a mirror, represented in profile, in which she is looking at herself; near her stands a maid, holding in her right hand a pot of ointment, in the left some undetermined object, perhaps a pin-cushion.

Ironing and Clothes Cleaning in Ancient Greece

The earliest known clothes iron comes from 4th century B.C. Greece. It was a rolling-pin-like metal cylinder rolled over linen fabric to get rid of wrinkles and make pleats. Ironing was a laborious and time-consuming chore usually done by slaves. A vase picture shows us two women occupied in folding some kind of embroidered garment; on the left another woman is turning round to look at them; on the floor stand a chair and a chest, on the wall hang a mirror and a garment.

Spindle whirls from the 10th century BC

Simple woollen clothes, as well as linen garments, were, of course, washed at home. The charming description in the “Odyssey” of Nausicaa, who goes with her companions to the sea-shore to wash the clothes, is well known; doubtless similar scenes might be seen in later times, even though no king’s daughter took part in them, and no god-like hero alarmed the maidens by his unexpected appearance. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

A vase picture shows how an artist of the fifth century imagined that scene in Phaeacia, according to the analogy of his own time. On the left side of the picture, not represented here, stand Odysseus and Athene, and several articles of clothing are hanging up to dry on the branches of a tree; on the right, which is here represented, some girls are engaged in hanging out the clothes. The finished, or newly-washed, clothes were then carefully folded and laid in chests, since wardrobes for hanging up dresses, such as we have, seem to have been unknown.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024