Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

BEAUTY IN ANCIENT GREECE

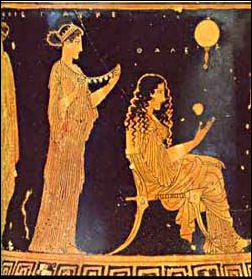

Aristotle once said "beauty is a far greater recommendation than any letter of introduction." Unlike the Egyptians and Romans, who used lots of make-up and perfume and wore flashy hairstyle, the Greeks preferred the natural look. The unadorned male body in particular was glorified in sport and sculpture. Make up was associated courtesans.

Both Aesop (of the fables) and Socrates were described as ugly.

Aristotle once said "beauty is a far greater recommendation than any letter of introduction." Unlike the Egyptians and Romans, who used lots of make-up and perfume and wore flashy hairstyle, the Greeks preferred the natural look. The unadorned male body in particular was glorified in sport and sculpture. Make up was associated courtesans.

Both Aesop (of the fables) and Socrates were described as ugly.

The customs of make up, coiffed hair and perfume were kept alive by courtesans. They even freshened their breath with aromatic liquids that they rolled around in the mouth and on their tongue. The use of cosmetics was looked down upon on ordinary women. The 4th century historian Xenophon wrote: "When I found her painted, I pointed out that she was being dishonest in attempting to deceive me about her looks as I should be were I to deceive her about my property."

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The ancient Greeks and Romans were somewhat looks-obsessed: they provide us with wildly racist handbooks that use bodily characteristics to determine and dissect a person’s character. According to these and broader consensus, you could tell the kind of person you were dealing with from their appearance.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 15, 2020]

Descriptions of a person’s physical appearance could go far beyond just the color of their hair, eyes, and skin. Everything from the tenor of a person’s voice to the way that they carried themselves was up for debate. Plutarch tells us about how Alexander the Great smelled: he had a “very pleasant odour [that] exhaled from his skin” and filled his garments. In a world without deodorant this is quite an advantage. A description of a self-emancipated third century slave refers to both his honey-colored skin and the fact that he walks around like a bigshot “yapping in a shrill voice.” Dr. Robyn Faith Walsh, assistant professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at University of Miami, told The Daily Beast that “it was normal and quite expected across a variety of literary genres to describe the physical appearance of central figures”.

It’s worth noting that Jesus isn’t the only famous ancient teacher who is described in this way. Aesop, the enslaved man responsible for the fables we still read to our children, and Socrates, the famous philosopher, were both described as unattractive. Aesop receives particularly harsh treatment he had “loathsome aspect… [was] potbellied, misshapen of head, snub-nosed, swarthy, dwarfish, bandy-legged, short-armed, squint-eyed, liver-lipped — a portentous monstrosity.” The Apostle Paul was, similarly, described as balding, sporting a unibrow, and bandy-legged but despite all of this was still quite a hit with the ladies.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity”| by Mary Harlow (2022) Amazon.com;

“Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art: Art and Thought in Ancient Greece”

by Ian Jenkins (2015) Amazon.com;

“Pearls and Petals Beauty Rituals in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Jewellery” by Filippo Coarelli (1970) Amazon.com;

“The Secrets of Classical Beauty: Exploring Greek Aesthetics in Art and Thought”

by Nava Sevilla Sadeh (2022) Amazon.com;

“Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea” by David Konstan (2017)

Amazon.com;

“Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece” by Mireille M. Lee (2015) Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume I: Books 1–4" (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“The Bath in Greece in Classical Antiquity: The Peloponnese” by Maria-Evdokia Wassenhoven (2012) Amazon.com;

“Costumes of the Greeks and Romans” by Thomas Hope (1962) Amazon.com;

“Dress in Mediterranean Antiquity: Greeks, Romans, Jews, Christians” by Alicia J. Batten, Kelly Olson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek, Roman & Byzantine Costume” by Mary G. Houston (2011)

Amazon.com;

“Women's Dress in the Ancient Greek World” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2023) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Garments: Textiles in Greek Sanctuaries in the 7th to the 1st Centuries BC” by Cecilie Brøns (2017) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z” by Liza Cleland, Glenys Davies, et al. (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Phi Ratio and the Ancient Greek Idea of Beauty

Esquire magazine said beauty “all comes down to an ancient Greek philosophy called the Phi ratio, which Julian De Silva, M.D., of the Centre for Advanced Facial Cosmetic and Plastic Surgery used along with computer facial mapping to determine which famous women have the ideal face ratio and symmetry. While standards of beauty vary by culture, the ratio method is an interesting approach to aesthetics and may give us some clues as to why some people stand out more than others.” [Source: Esquire]

According to Dr Anushka Reddy’s Medi-Sculpt Aesthetics and Anti-Aging Solutions website: “Some 2,500 years ago, in Ancient Greece, it was discovered that when a line is divided into two parts in a ratio of 1: 1.618, it creates an appealing proportion. This ratio is known as the golden ratio, the divine proportion or phi (named after Phidias, a Greek sculptor and mathematician who used this ratio when designing sculptures).[Source: Dr Anushka Reddy, Medi-Sculpt Aesthetics and Anti-Aging Solutions website.

“We may be unaware of it but we subconsciously judge beauty by facial symmetry and proportion. Cross-cultural research has shown that no matter the ethnicity, our perception of beauty is based on the ratio proportions of 1.618. As the face comes closer to this ratio, it is perceived as more beautiful. As an example, the ideal ratio of the top of the head to the chin versus the width of the head should be 1.618.

“We may be unaware of it but we subconsciously judge beauty by facial symmetry and proportion. Cross-cultural research has shown that no matter the ethnicity, our perception of beauty is based on the ratio proportions of 1.618. As the face comes closer to this ratio, it is perceived as more beautiful. As an example, the ideal ratio of the top of the head to the chin versus the width of the head should be 1.618.

How do we use the golden ratio to measure the ideal facial proportions? 1) the distance from the top of the nose to the centre of the lips should be 1.618 times the distance from the centre of the lips to the chin. 2) the hairline to the upper eyelid should be 1.618 times the length of the top of the upper eyebrow to the lower eyelid. 3) the ideal ratio of upper to lower lip volume is 1:1.6 (the lower lip should have slightly more volume than the upper lip)

“At Medi-Sculpt we achieve this by using FDA approved dermal fillers and botulinum toxin such as Botox to enhance and rejuvenate facial proportions: 1) If your face is long and narrow, Dr Reddy uses fillers to enhance the width of the cheekbones or if the lower face is too short, she can enhance the jawline and even extend and add symmetry to the chin using fillers. 2) If the temple area is sunken, Dr Reddy used dermal fillers to restore the volume and add proportion to the eye area. 3) If a too-high forehead is an issue, she can inject botulinum toxin such as Botox to raise the eyebrows. 4) A non-surgical lip augmentation can reduce your lower facial height.

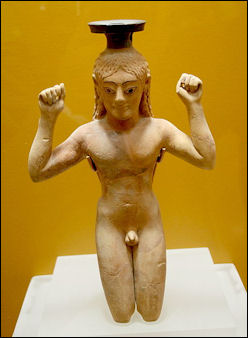

Ancient Greek View of a Beautiful Body

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Over two thousand years the Greeks experimented with representing the human body in works that range from abstract simplicity to full-blown realism. In athletics the male body was displayed as if it were a living sculpture, and victors were commemorated by actual statues. In art, not only were mortal men and women represented, but also the gods and other beings of myth and the supernatural world. They were either conceived in the image of humankind or in monstrous combinations of human and animal form. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, October 15, 2010, npm.gov.tw \=/ ]

“If we look for an overarching definition of the Greek body, it has to be its humanism. Interest in the human self motivates much of that which we now regard as innovative in ancient Greek culture. In drama, philosophy, written history, scientific medicine and the natural sciences at large, Greeks were the first to direct the human mind on its modern quest for self-knowledge. The development of the human body in art as object of beauty and bearer of meaning was driven by the ancient Greek lust for life and constant enquiry.

Cosmetics in Ancient Greece

Greeks and Roman used an arsenic compound to remove hair and cinnabar, a poisonous red sulfide of mercury, for lipstick and rouge. One of the most popular forms of make-up was cheek rogue. Worn by both men and women, it was made from plant substance such as seaweed or mulberry mixed with highly toxic cinnabar.

Greek women made use of many cosmetics. They not only anointed their bodies with fragrant essences and their hair with sweet-scented oils and pomades, but the practice of rougeing was also a very common one. The Spartan women, whose healthy complexions were celebrated, probably made little use of it; but the ancient writers supply sufficient testimony to its commonness at Athens. This practice may have originated in the East, and its great popularity among Ionic-Attic women is probably due to the fact that want of fresh air and exercise gave them a pale, sickly complexion, and they therefore considered it necessary to improve it artificially, though it were only to please their own husbands. They supplied the tender colouring of forehead and chin with white lead, the redness of their cheeks with cinnabar, fucus, and bugloss, or other (usually vegetable) dyes; there was a special flesh tint used for painting below the eyes. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Greek women The eyebrows were dyed with black paint, which was made of pine blacking or pulverised antimony, and dyeing the hair was quite common as early as the fifth century B.C., and by no means unusual even among men. The rouge was put on either with the finger or a little brush. In vain the poets, especially the comic writers, aimed the sharpest arrows of their wit at this evil practice; in vain they described in drastic colours how, in the heat of summer, two little black streams poured down from the eyes over the face, while the red colour from the cheeks ran down to the neck; and the hair falling over the forehead was dyed green by the white lead.

The best cure would doubtless have been found, if every man had been as sensible as the young husband described in Xenophon’s story alluded to above, who cured his wife of rougeing by representing to her the absurdity of this practice, showing her how impossible it was for a woman to deceive her own husband in this way, since the truth might come to light at any moment. He also advised his wife not to spend the whole day in her room, but to move about the house, superintend the servants’ work, help the housekeeper, and herself lend a hand in kneading the dough, and other such occupations, while supplying exercise for herself by shaking out and folding up the clothes. Then she would have a better appetite for her meals, be in better health, and naturally have a better complexion. But such sensible husbands were rare, and probably all the women were not so obedient as the wife of Ischomachus.

Olive oil and fat were commonly used in ancient Greek cosmetics and beauty aids. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The medic Hippocrates notes over sixty uses for olive oil in his writings, but by far the most common was the use of olive oil to moisturize and protect the skin. Both ancient Greek athletes and the patrons of the Roman baths used olive oil as a cleanser and moisturizer. They would begin by lathering themselves in oil and using a strigil (a curved blade almost always made of metal) to scrape off the dirt, sweat, and oil before bathing. [Source:Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 23, 2017]

Olive oil was the most common cleanser-hydrator, but there were plenty of other fat-based options. The hydrating properties of beeswax continues to be used today, but animal fats were the go-to ingredients for ancient soap. Babylonians were making soap from animal fats around 2800 B.C., and similar techniques can be noted among ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians (the Phoenicians used goat’s tallow and wood ashes in theirs) before the turn of the millenium.A number of ancient Greek and Roman medics hypothesized that semen was concentrated blood, making it an especially potent emission for the preservation of life. If a young woman did not have sex at all she was liable to suffer from a disease called, somewhat self-explanatorily, the Disease of the Virgins. The name was coined in the sixteenth century, and the ailment could leave you wasting away with unattractive greenish pale skin.

Pale Skin in Ancient Greece

The pale complexion a woman received from staying indoors all the time was seen as a sign of virtue and beauty. Some women whiten their faces, bosoms and necks with a white powder made from lead. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Tanning as a practice is a relatively new arrival to the beauty scene; until the nineteenth century pallor was the skin tone of choice. And people employed a whole host of dangerous beauty treatments in order to achieve it. For the ancient Greeks and Romans a pale complexion was deemed the most desirable. Roman love poetry extols the merits of the radiantly white girl and Greek mythology admires the pale-armed heroines and goddesses like Andromache and Hera. Paleness was seen as a marker of beauty but also, for some, as an indication of character. Aristotle’s Physiognomy relates that “a vivid complexion shows heat and warm blood, but a pink-and-white complexion proves a good disposition.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, September 4, 2016]

More than character, however, pale skin was a marker of social status and class. It was a sign that women (and men) did not have to engage in the kind of menial work that would take them outside into the sun. In women paleness had a kind of moral dimension: it was a sign that a woman had remained in the household and, as Caesar might put it, was “above reproach.”

Paleness, of course, is relative. Life in southern Italy and Greece does not lend itself to pallor and, thus, Roman aristocrats turned to cosmetics: predominantly chalk but sometimes also lead to whiten their faces. They weren’t alone. Their medieval counterparts used lotions made of violet and rose oil to protect their skin from the sun. It’s difficult to imagine these sunscreens were effective but, then again, many modern sunscreens also fall short.

Ancient Greek Tattoos

Unlike today's tattoos which are primarily decorative, tattoos in antiquity primarily had punitive, magical and medical purposes and were used to identify slaves and undesirables. The custom was so widespread there were professional tattooers who specialized in slaves, criminals and prisoners. Persians, Greeks, Romans, Scythians, Dacians, Gauls, Picts, Celts and Britons all practiced tattooing . Tattooing were probably introduced to Greece from Persia around the 6th century B.C. But the custom goes back much further than that. Otzi, the 5,500-year-old ice man found in Italian Alps, had tattooed parallel lines on his right foot and ankle, bars along his lower spine, lines at his left calf, and crosses inside his right knee. [Source: Adrienne Mayor, Archaeology, March/April 1999]

Tattoos in ancient times were generally made by pricking the skin with needles and rubbing ink or soot into the wounds. Punitive tattoos were often gouged into the skin with three needled bound together for a thick line. Infection and heavy bleeding were common. Sometimes victims died.

perfume bottle According to the historian Herodotus, Greeks learned the idea of penal tattoos from the Persians in the sixth century B.C. Tattooing captives in wartime was common. A famous example has the Athenians tattooing the defeated Samians only to have the favor returned when the Samians defeated the Athenians.After Athens defeated the Aegean island of Samos in the fifth century B.C., the Athens leaders ordered the foreheads of prisoners of war to be tattooed with an owl, the emblem of Athens. When Samos late defeated Athens, the foreheads of the Athenian prisoners of war were tattooed with an image of a Samos warship. A similar fate befell 7,000 Athenians, who were tattooed with images of horses, the symbol of Syracuse, after they were defeated at Syracuse.

Among some of the ancient cultures the Greeks encountered — Thracians, Scythians, Dacians and Celts — tattoos were seen as marks of pride. Herodotus said the Thracians found fair skin unattractive men and women with tattoos were greatly admired, and “tattooing among them marks noble birth, and the want of it low birth.”. Thracians who were marked with prisoner of war tattoos had them embellished into decorative tattoos. Among the Mossynoikoi, who lived on the Black Sea in the fifth century B.C., the historian Xenophon observed, "the chubby children of the best families were entirely tattooed back and front with flowers in many colors." A fifth-century B.C. Greek vase (left) depicts a tattooed Thracian maenad, a female follower of the god Dionysus, killing the musician Orpheus as punishment for abandoning Dionysus to worship the sun god, Apollo. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2013]

In 3rd century B.C. Greece there was a law that allowed masters to tattoo "bad" slaves but forbade the tabooing of "good" ones. A Hellenistic curse read: "I will tattoo you with pictures of terrible punishments suffered by the most notorious sinners in Hades! I will tattoo you with the white-tusked boar."

The Greeks also reportedly used tattoos of animals and geometric shapes to highlight musculature and motion. Figures on vases and kraters often feature tattoos of parallel lines, sunbursts, chevrons, circles, vines, ladders, spirals, zigzags, spirals and stylized animals.

Perfumes in Ancient Greece and Rome

Greek men scented different parts of their body with different perfumes. Writers in 400 B.C. suggested almond oil for the hands and feet, mint for the arms, thyme for the knees, rose, cinnamon or palm oil for the jaws and chest, and marjoram for the hair and eyebrows. Some politicians found use of these of fragrances to be so obsessive they suggested passing laws banning them.

Greeks used perfumed oils based on Egyptian recipes as deodorants. Alexander the Great was fond of perfumes and incense. He had his tunics soaked in the scent of saffron.

The ancient Greeks made perfumes and medicines from roses and added lavender oil to public baths. They also used tangerine, orange and lemon as scents and kept perfumes in translucent alabaster flasks. The Romans poured rose water in their baths and released aromas into the air during banquets and orgies with perfumed white doves that dispensed scent as they flew about. Rich Roman aristocrats slept on pillows stuffed with saffron when they suffered a hangover.

Hairstyles in Ancient Greece

Long hair at least in the early was greatly esteemed by ancient Greeks. Short hair was associated with barbarianism. Greek men had beards and long hair. Shaving didn't become widespread until the Roman era. The razor, in fact, was considered a woman's toiletry article. Women wore their hair long, unless they were a slave or in mourning, then they sported a bob. The long hair of non-mourning women was gathered, curled, tied and bound in bonnets and bows according to fashion. Greek actors sometimes wore wigs. Greeks and Romans used a variety of hairpins. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

Upper class Greek culture is the first known culture to prize light or blond hair. It was equated with desirability and innocence. Many Greek heros such as Achilles, Meenelaus and Paris had light hair. Some Greeks lightened their hair with soaps and alkaline bleaches available from Phoenicia. Some courtesans died their hair with a concoction made from apple-scented yellow flowers, pollen and potassium salts. Men it seemed were more found of lightening their hair than women. They used yellow pollen, yellow flour and even gold powder. The 4th century dramatist Menander wrote: "After washing their hair with a special ointment made in Athens, they sit bareheaded in the sun by the hour, waiting for their hair to turn a beautiful golden blond. And it does."

The hair was worn long by men until the fifth century B.C., and the Spartans and Athenian gentlemen who admired Spartan ways continued the fashion. It was sometimes allowed to fall on the shoulders in curls or braids, but was more frequently braided in two plaits and wound around the head, or made into a sort of roll at the back and fastened by a gold pin. In the sixth century men B.C. wore pointed beards without moustaches, but later it became customary to shave the entire face, though short beards and moustaches were worn by older men. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

A warrior on an amphora has a pointed beard and long hair. His young squire, who stands behind him, is beardless but his hair is long and curling. The lyre-player on a large amphora has long hair in a knot at the back, held in place by a band. A somewhat similar arrangement is seen in the bronze statuette of Apollo. The fashion of plaited hair wound around the head is illustrated by a terracotta relief of Phrixos on the ram’s back. In the fifth century B.C. short hair was usual for both young and old men; young men did not wear beards but older men frequently wore short beards with moustaches. A moustache without a beard was regarded as the mark of the barbarian. The marble heads of two young men, show the fashion for young men, and a comparison of other vases and small bronzes that make clear the gradual change of style from elaboration to simplicity.

The styles of women’s hair-dressing can be best understood by looking at the statues, vases, and terracottas in the collection. A variety of ornamental kerchiefs was worn, especially a very pretty band called sphendone, “sling,” from its shape. A large stamnos decorated with groups of women dressed in the Ionic and Doric chitons and wearing various kinds of head-dresses. Many terracottas and the head of a young goddess illustrate the “melon” coiffure which became the mode in the fourth century.

Men’s Hairstyles in the Heroic Era of Ancient Greece (700 B.C.)

In the heroic period long curly hair was regarded as a suitable ornament for a man. This is proved by the favorite epithet, “The curly-haired Achaeans,” and by other quotations from epic poetry; various indications prove that the curls were not always left to fall naturally, but that artificial means were sometimes adopted for facilitating and preserving their regular arrangement. When the “effeminate Paris” is said to rejoice in his “horn”, old commentators state that this horn was a twisted plait. It is possible that this might be produced by the mere use of stiffening pomades or other cosmetic means, which had been introduced from the East in the Homeric period; but the statements in the Iliad about the gold and silver “curl-holders” of the Trojan Euphorbus clearly point to artificial aids. The oldest sculptures and vase pictures give sufficient proof that this mode of wearing the hair in regular curls continued for a long time, for they almost always represent hair falling far down the neck, generally in regular stiff locks with horizontal waving, while small curls surround the forehead, arranged with equal accuracy. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

As to the means employed for producing these curls, Helbig’s opinion is that the spirals of bronze, silver, or gold wire found in old graves in several parts of the Old World were used as a foundation for the curls, which were twined around them. Certainly these spirals have often been found in Etruscan graves, near the spot where the head rested, and generally one on each side. This might, however, be explained by the other interpretation that they were a kind of primitive ear-ring. Perhaps the “gold and silver” with which Euphorbus “bound together” his locks, according to Homer, was not a particular kind of adornment, but only flexible gold and silver wire.

The monuments as well as the writers teach us that men wore their hair long, in the next period also, down to the fifth century; we sometimes find hair of such length and thickness depicted that it seems almost incredible that a man’s hair could have been so much developed, even by the most careful treatment. However, it did not often hang quite loose, but it was tied back somewhere near the neck by a ribbon, and, unlike the Homeric head-dress, where each curl is separately fastened, the whole mass of hair was bound together, and then spread out again below the fastening, and fell down the back. Sometimes the hair, after being tightly tied together in one place, was interwoven with cords or ribbons lower down, so that it fell in a broader mass than where it was tied together, but by no means hung loose. Another kind of head-dress is that in which the hair is tied together in such a manner as to resemble a broad and thickish band, something like our head-dress of the last century. The hair falls a little way below the neck, and is then taken up again and tied in with the other piece by a ribbon in such a manner that the end of the hair falls down over this ribbon. Here, too, we find variety, for the hair sometimes fell some way down the back, sometimes was fastened up again at the back of the head. An example of the former kind is the bronze head from Olympia.

Men’s Hairstyles in Classical Era of Ancient Greece

Most commonly, however, in the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. men plaited their long hair and laid the plaits round their head. There were two distinct modes of doing this. One was to take two plaits from the back of the head in different directions and fasten them like bandages round the head; the other was to begin the plaits at the ears, turn them backwards so that they crossed each other at the back of the head, then bring them round to the front and knot them together over the center of the forehead. This is the head-dress of the figure on the Omphalos known as Apollo, and the head of a youth. There are also many other differences in detail; sometimes he two plaits were laid across the hair from the parting to the forehead in the form of a fillet holding the hair fast, as in the marble head; but sometimes the front hair is laid across the ends of the plait fastened together in front, as in the head from a vase painting. The head shows a peculiar mode of treating the back hair. The lower part of this is plaited, and the plait turned up again and fastened where the other two braids cross each other. Other plaits also fall from behind the ears in regular arrangement over the shoulders in front, often reaching as far as the breast. The hair on the forehead is dressed with equal care. With this fashion also the regular little curls, arranged in one or more rows round the forehead, are very common. Sometimes they are in spiral form, sometimes in that of “corkscrew” curls, as on the archaic bronze head from Pompeii. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

These are the principal archaic modes of wearing the hair found on the monuments, but they by no means exhaust the varieties which might be observed. The writers, however, only mention one ancient head-dress. Thucydides, in the passage already quoted, which describes the long chitons formerly worn by the Athenians, also tells us that at the same time that this old-fashioned dress was abandoned, the Athenians gave up the old way of dressing their hair in the crobylus (κρωβύλος), into which they fastened golden grasshoppers. It has not yet, however, been possible to determine with any certainty which of the head-dresses found on the statues corresponded to this crobylus, which seems to be identical with the corymbus (κόρυμβος) mentioned in other places; nor has it been possible to find any traces of the grasshoppers. Consequently almost all the head-dresses above described have been claimed for the crobylus, even the double plaits behind the ears; and the grasshoppers have been explained sometimes as the above-mentioned spirals, sometimes as hair-pins or fibulae. Perhaps some day a fortunate discovery may throw light on this difficult question.

It would be scarcely possible to assign a chronological order to all these various archaic head-dresses. However, in the latter half of the fifth century they all disappear, and here we have another proof of the increasing aesthetic sense noticeable in all domains of life in the classic period. The allusions in Aristophanes show that in his time it was only old-fashioned people, who probably also went about in long chitons, who still wore the grasshoppers. From the time of Pheidias, the elaborate head-dresses entirely vanish; and though they are continued for a longer period on the vase paintings, that is probably because painting adhered longer than sculpture to the old forms and fashions, since its free development in style was also of later growth. After this time the long, flowing hair of the men, and the pigtail disappear; and though only youths and athletes wore their hair quite short, yet the men’s hair was also shortened, and owed its chief beauty to nature, which has granted the gift of graceful curl to Southern and Asian nations.

The portrait heads of this and the following period depict the hair as simply curled, soft, and not too abundant. This seems to have continued during the following centuries; at any rate, the monuments show no trace of a return to the artificial head-dresses fashionable in ancient times. Just as wigs, powder, and pigtails have disappeared for ever among us, so antiquity, when it had once recognised the beauty of hair in its natural growth, never returned to the stiff and laborious head-dress of the past. Of course, there were various fashions in the mode of wearing the hair and having it cut; in fact, there are a number of different names for the modes of cutting it, such as the “garden,” the “boat,” but we do not know what these were like, since the monuments afford no clue. Probably it was only dandies who laid any stress on such matters. It is but natural that there should have been many local variations in the mode of wearing the hair, as in the dress, and probably these were of some importance in the oldest period; but we know very little about them. At Sparta it was the custom at the time of the Peloponnesian War to shave the hair quite close to the head, but as the Spartans wore long, carefully-curled hair at the time of the Persian wars, a change in the fashion must have taken place at Sparta in the course of the fifth century.

No special ornaments were worn in the hair by men after they gave up the old-fashioned curl-holders and the mysterious grasshoppers. The “band” or fillet laid round the forehead, which Dionysus commonly wears in works of art, was only actually used as the reward of victory in gymnastic or other contests. The diadem is a token of royal dignity, and, therefore, unknown in free Greece.

Beards and Shaving in Ancient Greece

The change of fashion in the mode of wearing the beard can also be traced in Greek antiquity. There is no direct account of it in the Homeric poems, but probably some indirect hints. A well known simile in Homer mentions the razor. As the Achaeans wore their hair long, and certainly were not smooth shaven, the question arises, what use they could have made of the razor. Helbig points to the analogy of the Egyptian and Phoenician custom, which had considerable influence on Hellenic culture, and also shows, by means of old Greek monuments, that very probably the Ionians of the Homeric period shaved the upper lip; as, in fact, the Dorians also did in older times. It is true this period must have been preceded by an older one unacquainted with this custom, for the gold masks found in graves at Mycenae bear a moustache; and the best example of these is treated in such a way as to point to the use of some stiffening pomade, as well as the artificial cutting of the moustache. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The monuments also show us that the custom of shaving the upper lip continued for some time in the following centuries; but it was not the only prevailing one, for we also find whiskers, beard, and moustache. It is but natural that in the period when the hair was elaborately dressed, special care was taken also with the treatment of the beard. It was not only regularly cut, and usually in a point, but it was also cut short at certain places, especially between the lower lip and the chin, so that the part thus treated presented a different appearance from the rest of the beard. They also curled the moustache, and arched it upwards; and if we may believe the testimony of archaic monuments, we must assume that curling-irons were sometimes used for the artificial arrangement of the beard. It was not till the latter half of the fifth century that the beard was allowed to fall naturally and simply, at the time when they began to treat the hair in a similar manner.

The beard, although not entirely abandoned to its natural growth, since it was cut into a shape corresponding to the oval of the face, instead of the former point, at any rate was no longer treated by artificial means, such as pomades, elaborate curling, etc. The portrait type of Pericles or Sophocles shows us the finest example of a simple and dignified mode of wearing the beard, while the ideal head of Zeus from Otricoli, with its artificially parted beard, in spite of the grandeur of the treatment, is far removed from the classic simplicity of the age of Pheidias. After Alexander the Great and his successors it became the custom to shave the whole face. The portrait statues show us that old men especially, who had formerly allowed their beard to grow, now almost always shaved it off. Aristotle, Menander, Poseidippus, the princes of the Alexandrine age, etc., have smooth-shaven faces. Youths and middle-aged men at that period sometimes let their beard grow, but old men only did so when they wished to indicate, by a long, ragged beard, that they were followers of the Cynic school; for even down to the time of the Empire the long beard was the distinguishing mark of the philosopher.

Women’s Hairstyles in Ancient Greece

The head-dress of women also underwent many changes. We do not know how their hair was bound up and arranged in the Homeric period, when it was treated with sweet-scented oils and pomades, which were, in fact, very common during the heroic period. Mention is especially made of a cap-like arrangement of the hair, and a plaited braid connected with it. Helbig believes he has recognised the same fashion in the women’s head-dress on old Etruscan pictures, on which it is possible to distinguish a high-pointed cap and a band laid over it. However this may be, Andromache’s head-dress, as described by Homer, has a distinctly Asian character. In the next period the works of art are again our best guide. They show us that, apart from external ornament, the head-dress of men and women in ancient times was essentially similar.

We find the long hair either falling freely or in single plaits down the back; curls falling on the shoulders; and little ringlets surrounding the forehead; we find the hair tied up at the back of the neck, or the mode described above of tying it up in band-like fashion in several places. We also find that arrangement of double plaits laid several times round the back of the head, which has been claimed as the crobylus, although this is only mentioned as a male head-dress. This last fashion is even found in the graceful Caryatides of the Erechtheum, but here it is probably a reminiscence of the old custom, natural in these female figures, which are, as it were, in the service of the goddess. Otherwise none of these fashions continue beyond the last quarter of the fifth century, either for women or men.

About the middle of the fifth century the fashion of wearing many-coloured kerchiefs, covering the greater part of the hair, must have been very prevalent. Polygnotus paints his women thus, and we find the same fashion in the pediments of Olympia, and on some of the female figures on the Eastern Parthenon frieze, and on numerous vase paintings of that period. But at the same period, when the men began to emancipate themselves from the stiff head-dresses, and to wear their hair in a natural manner, a simple and beautiful fashion also became commoner among the women. The hair was usually parted in the middle and either fell in slight ripples loosely down the back or else was drawn up into a knot at the back of the head. The latter fashion, which we still call the “Greek knot,” is the commonest and most beautiful in the next period too. Sometimes the knot fell far down the neck, which was certainly the most graceful, or else it was higher up the head, where the hair is combed upwards from the face, or else the knot developed into a flattened nest or wreath.

A simple ornament frequently found is a narrow band or fillet entwined with the hair or laid around the hair and forehead. Kerchiefs were also much worn afterwards, sometimes put on in such a way as to cover almost the whole hair, sometimes only a part, so that the hair at the back of the head is visible beneath it. There were also a variety of metal ornaments, which were fastened into the hair either to keep it firm or else for decorative purposes — golden circlets or diadems, pins, etc. Detailed consideration of these ornaments show us that the age of Pericles and that immediately following it, were the periods when the style and technique attained their highest development and artistic beauty. Thus dress, hair, and ornament all combined harmoniously to represent the people of that age in surroundings corresponding in the fullest degree to the poetic and artistic attainments of the epoch.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024