Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

MASTURBATION, FELLATIO AND IRRUMATION IN ANTIQUITY

Actor The Roman poet Martial (A.D. 40-104) in one of his epigrams wrote: 'Veneri servit amica manus' — 'Thy hand serves as the mistress of thy pleasure.' He also discussed Phrygian slaves masturbating themselves to overcome the amorous feelings which the sight of their master having connection with his wife provoked in them. Martial has many allusions. He tells us that Mercury taught the art to his son Pan, who was distracted by the loss of his mistress, Echo, and that Pan afterwards instructed the shepherds. Mirabeau mentions a curious practice which he declares to be prevalent amongst the Grecian women of modern times: that of using their feet to provoke the orgasm of their lovers. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: Aristophanes, in the Wasps, touches on the subject, and one of the most charming of the shorter poems of Catullus contains an allusion: O Caelius, our Lesbia, Lesbia, that Lesbia whom Catullus more than himself and all his kin did love, now in the public streets and in alleys husks off the magnanimous descendants of Remus.

“The tertia poena (third punishment) referred to in Epigram 12 on page 42 is irrumation or coition with the mouth. The patient (fellator or sucker) provokes the orgasm by the manipulation of his (or her) lips and tongue on the agent's member. Galienus calls it lesbiari (Greek lesbiázein), as the Lesbian women were supposed to have been the introducers of this practice. Lampridius says: “That lecherous man, whose mouth even is defiled and dishonest.” Minutius Felix says:(They who lick men's middles, cleave to their inguina with lustful mouth). He refers to the ancient belief that the raven ejected the semen in coition from its beak into the female, a belief that Aristotle refuted.

“The Phoenicians used to redden their lips to imitate better the appearance of the vulva; on the other hand the Lesbians who were devoted to this practice whitened their lips as though with semen. The word 'husking' used by Glubit can be interpreted as describing irrumation or masturbation. Plutarch says that Chrysippus praised Diogenes for masturbating himself in the middle of the marketplace, and for saying to the bystanders: 'Would to Heaven that by rubbing my stomach in the same fashion, I could satisfy my hunger.'”

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEX IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PROSTITUTES AND COURTESANS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HOMOSEXUALITY IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Sexual Life in Ancient Greece” by Hans Licht (1993) Amazon.com;

“Controlling Desires: Sexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Kirk Ormand (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sex on Show: Seeing the Erotic in Greece and Rome” by Caroline Vout (2013) Amazon.com;

“Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture” by Marilyn B. Skinner Amazon.com;

"Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook" (Routledge)

by Marguerite Johnson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Sexualities: A Sourcebook” (Bloomsbury Sources) by Jennifer Larson (2012) Amazon.com;

“Sex in Antiquity: Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the Ancient World” by Mark Masterson, Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Houses of Ill Repute: The Archaeology of Brothels, Houses, and Taverns in the Greek World” by Allison Glazebrook and Barbara Tsakirgis (2016) Amazon.com;

“Eros: The Myth Of Ancient Greek Sexuality” by Bruce S Thornton (2018)

Amazon.com;

“The Sleep of Reason: Erotic Experience and Sexual Ethics in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Martha C. Nussbaum , Juha Sihvola (2002) Amazon.com;

“Intimate Lives of the Ancient Greeks” by Stephanie L. Budin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece” by Susan Blundell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Bonnie MacLachlan (2012) Amazon.com;

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Courtesans & Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens” by James Davidson (1997) Amazon.com;

“Love Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Sofia A Souli (2018) Amazon.com;

“Love in Ancient Greece” by Robert Flacelière (1962) Amazon.com;

“In the Orbit of Love: Affection in Ancient Greece and Rome” by David Konstan (2018) Amazon.com;

“Revisiting Rape in Antiquity: Sexualised Violence in Greek and Roman Worlds”

by Susan Deacy, José Malheiro Magalhães, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks and Greek Love: a Radical Reappraisal of Homosexuality in Ancient Greece”

by Davidson James (2007) Amazon.com;

“Female Homosexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Sandra Boehringer (2021) Amazon.com;

Bestiality and Greco-Roman Gods

Silenus The following passage from The Golden Ass by Apuleius (A.D. 125-170), a Carthage-based Latin-language prose writer and Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. “The mother of the Minotaur was Pasiphaë, the wife of King Minos. Burning with desire for a snow-white bull, she got the artificer Daedalus to construct for her a wooden image of a cow, in which she placed herself in such a posture that her vagina was presented to the amorous attack of the bull, without fear of any hurt from the animal's hoofs or weight. The fruit of this embrace was the Minotaur — half bull, half man — slain by Theseus. According to Suetonius, Nero caused this spectacle to be enacted at the public shows, a woman being encased in a similar construction and covered by a bull. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

“The amatory adventures of the Roman gods under the outward semblance of animals cannot but be regarded with the suspicion that an undercurrent of truth runs through the fable, when the general laxity of morals of that age is taken into account. Jupiter enjoyed Europa under the form of a bull; Asterie, whom he afterwards changed into a quail, he ravished under the shape of an eagle; and Leda lent herself to his embraces whilst he was disguised as a swan. He changed himself into a speckled serpent to have connection with Deois (Proserpine). As a satyr (half man, half goat), he impregnated Antiope with twin offspring. He changed himself into fire, or, according to some, into an eagle, to seduce Aegina; under the semblance of a shower of gold he deceived Danaë; in the shape of her husband Amphitryon he begat Hercules on Alcmene; as a shepherd he lay with Mnemosyne; and as a cloud embraced Io, whom he afterwards changed into a cow. Neptune, transformed into a fierce bull, raped Canace; he changed Theophane into a sheep and himself into a ram, and begat on her the ram with the golden fleece. As a horse he had connection with the goddess Ceres, who bore to him the steed Arion. He lay with Medusa (who, according to some, was the mother of the horse Pegasus by him) under the form of a bird; and with Melantho, as a dolphin. As the river Enipeus he committed violence upon Iphimedeia, and by her was the father of the giants Otus and Ephialtes. Saturn begat the centaur (half man, half horse) Chiron on Phillyra whilst he assumed the appearance of a horse; Phoebus wore the wings of a hawk at one time, at another the skin of a lion. Liber deceived Erigone in a fictitious bunch of grapes, and many more examples could be added to the list.”

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: “According to Pliny, Semiramis prostituted herself to her horse; and Herodotus speaks of a goat having indecent and public communication with an Egyptian woman. Strabo and Plutarch both confirm this statement. The punishment of bestiality set out in Leviticus shows that the vice was practised by both sexes amongst the Jews. Pausanius mentions Aristodama, the mother of Aratus, as having had intercourse with a serpent, and the mother of the great Scipio was said to have conceived by a serpent. Such was the case also with Olympias, the mother of Alexander, who was taught by her that he was a God, and who in return deified her. Venette says that there is nothing more common in Egypt than that young women have intercourse with bucks. Plutarch mentions the case of a woman who submitted to a crocodile; and Sonnini also states that Egyptians were known to have connection with the female crocodile. Vergil refers to bestiality with goats. Plutarch quotes two examples of men having offspring, the one by a she-ass, the other by a mare. Antique monuments representing men copulating with goats (caprae) bear striking testimony to the historian's veracity; and the Chinese are notorious for their misuse of ducks and geese.”

Sex Positions of Cyrene and Elephantis

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Pindar's 9th Pythian ode, Cyrene or Kyrene (Ancient Greek:"sovereign queen") was the daughter of Hypseus, King of the Lapiths, although some myths state that her father was actually the river-god Peneus. She was a nymph who gave birth to the god Apollo, Aristaeus and Idmon while with Ares. She alsi identified as the mother of Diomedes of Thrace. Cyrene was a fierce huntress, called by Nonnus a "deer-chasing second Artemis, the girl lionkiller." [Source: Wikipedia +]

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: 'Cyrene was a celebrated whore, known under the name of Dodecamechanos, as she knew how to do the amorous work in twelve positions.' In “Frogs,” Aristophanes speaks of the dozen postures of Cyrene. In “Peace,” Aristophanes says, “So that you may, by lifting up her legs, Accomplish high in air the mysteries.” In “Birds,” he writes: “Of the girl you sent, I lifted first her feet, And entered her domain.” [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

“Elephantis was a Greek poetess who wrote on nine different sex positions in a famous sex manual that has been lost to time. According to Suidas, Astyanassa, the maid of Helen of Troy, was, the first writer on erotic postures, and Philaenis and Elephantis (both Greek maidens) followed up the subject. Aeschrion however ascribes the work attributed to Philaenis to Polycrates, the Athenian sophist, who, it is said, placed the name of Philaenis on his volume for the purpose of blasting her reputation. This subject occupied the pens of many Greek and Latin authors, amongst whom may be mentioned: Aedituus, an erotic poet noticed by Apuleius in his Apology: Annianus (in Ausonius); Anser, an erotic poet cited by Ovid; Aristides, the Milesian poet; Astyanassa, above mentioned; Bassus; Callistrate, a Lesbian poetess, noted for obscene verses.”

Elephantis (late 1st century B.C.) is credited with “setting out new modes of venery” ( pursuit of or indulgence in sexual pleasure). Due to the popularity of courtesans taking animal names in classical times, it is likely Elephantis is two or more persons of the same name. Elephantis was also a physician. Pliny references her performance as a midwife, and Galen notes her ability to cure baldness. She also wrote a manual about cosmetics and another about abortives. +

None of Elephantis works have survived, though they are referenced in other ancient texts. According to Suetonius, the Roman Emperor Tiberius took a complete set of her works with him when he retreated to his resort on Capri. One of the poems in the Priapeia refers to her books: "Lalage dedicates a votive offering to the God of the erect penis, bringing shameless pictures from the books of Elephantis, and begs him to try and imitate with her the variety of intercourse of the figures in the illustrations." And an epigram by the Roman poet Martial, which Smithers and Burton included in their collection of poems concerning Priapus, reads: "Such verses as neither the daughters of Didymus know, nor the debauched books of Elephantis, in which are set out new forms (“novae figura”) of lovemaking .") "Novae figurae" has been read as "novem figurae" (i.e., "nine forms" of lovemaking, rather than "new forms" of lovemaking), and so some commentators have inferred that she listed nine different sexual positions. +

Cunnilinges

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: Cunnilinges — defined as causing “a woman to feel the venereal spasm by the play of the tongue on her clitoris and in her vagina” — was a taste much in vogue amongst the Greeks and Romans. Martial lashes it severely in several epigrams, that against Manneius being especially biting. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

Catullus compares cunnilinges to bucks on account of their foetid breath; and Martial mocks at the paleness of Charinus's complexion, which he sarcastically ascribes to his indulgence in this respect. Maleager has a distich upon Phavorinus (Huschlaus, Anaketa Critica), and Ammianus (Brunck, Analecta) has written an epigram, both of which appear to be directed against the vice. Suetonius (Illustrious Grammarians) speaks of Remmius Palaemon, who was addicted to this habit, being publicly rebuked by a young man who in the throng could not contrive to avoid one of his kisses; and Aristophanes says of Ariphrades in Knights: ‘Whoever does not execrate that man, Shall never from the same bowl drink with us.’ According to Juvenal women were not addicted to exchanging this kind of caress with one another: 'Taedia does not lick Cluvia, nor Flora Catulla.'

“Many passages in the classics, both Greek and Roman, refer to the cunnilinges swallowing the menstrual and other secretions of women. Aristophanes frequently speaks of this. Ariphrades sods his tongue and stains his beard with disgusting moisture from the vulva. The same person imbibes the feminine secretion, 'And throwing himself on her he drank all her juice.' Galienus applies the appellation 'drinkers of menses' to cunnilinges; Juvenal speaks of Ravola's beard being all moist when rubbing against Rhodope's privities; and Seneca states that Mamercus Scaurus, the consul, 'swallowed the menses of his servant girls by the mouthful'. The same writer describes Natalis as 'that man with a tongue as malicious as it is impure, in whose mouth women eject their monthly Purgation.'

“In the Analecta of Brunck, Micarchus has an epigram against Demonax in which he says, 'Though living amongst us, you sleep in Carthage,' i.e. during the day he lives in Greece, but sleeps in Phoenicia, because he stains his mouth with the monthly flux, which is the colour of the purplish-red Phoenician dye. In Chorier's Aloisia Sigea, we find Gonsalvo de Cordova described as a great tongue-player (linguist). When Gonsalvo desired to apply his mouth to a woman's parts he used to say that he wanted to go to Liguria; and with a play upon words implying the idea of a humid vulva, that he was going to Phoenicia or to the Red Sea or to the Salt Lake--as to which expressions compare the salty sea of Alpheus and the salgamas of Ausonius and the 'mushrooms swimming in putrid brine' which Baeticus devours. As it was said of fellators (who sucked the male member) that they were Phoenicising because they followed the example set by the Phoenicians, so probably the same word was applied to cunnilinges from their swimming in a sea of Phoenician purple. Hesychius defines scylax (dog) as an erotic posture like that assumed by Phoenicians. The epithet excellently describes the action of a cunnilinge with regard to the posture assumed; dogs being notoriously addicted to licking a woman's parts. The reader who desires more information on the subject will find further details in Forberg, from whose pages I have drawn part of the material which constitutes this note.

“The word labda (a sucker) is variously derived from the Latin labia and do, to give the lips; and from the Greek letter lambda, which, is the first letter in the word leíchein or lesbiázein, the Lesbians being noted for this erotic vagary. Ausonius says, 'When he puts his tongue [in her coynte] it is a lambda'- that is the conjunction of the tongue with the woman's parts forms the shape of the Greek letter {lambda}. In an epigram he writes:

Lais, Eros and Itus, Chiron, Eros and Itus again,

If you write the names and take the initial letters

They will make a word, and that word you're doing, Eunus.

What that word is and means, decency lets me not tell.

(The initial letters of the six Greek names form the word leíchei, he licks)”

Sodomy in Antiquity

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: Paedico means to pedicate, to sodomise, to indulge in unnatural lewdness with a woman often in the sense of to abuse. In Martial’s Epigrams 10, 16 and 31 jesting allusion is made to the injury done to the buttocks of the catamite by the introduction of the 'twelve-inch pole' of Priapus. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

Orpheus is supposed to have introduced the vice of sodomy upon the earth. In Ovid's Metamorphoses: He also was the first adviser of the Thracian people to transfer their love to tender youths ...presumably in consequence of the death of Eurydice, his wife, and his unsuccessful attempt to bring her to earth again from the infernal regions. But he paid dearly for his contempt of women. The Thracian dames whilst celebrating their bacchanal rites tore him to pieces.

François Noël, however, states that Laius, father of Oedipus, was the first to make this vice known on earth. In imitation of Jupiter with Ganymede, he used Chrysippus, the son of Pelops, as a catamite; an example which speedily found many followers. Amongst famous sodomists of antiquity may be mentioned: Jupiter with Ganymede; Phoebus with Hyacinthus; Hercules with Hylas; Orestes with Pylades; Achilles with Patrodes, and also with Bryseis; Theseus with Pirithous; Pisistratus with Charmus; Demosthenes with Cnosion; Gracchus with Cornelia; Pompeius with Julia; Brutus with Portia; the Bithynian king Nicomedes with Caesar,[1] &c., &c. An account of famous sodomists in history is given in the privately printed volumes of 'Pisanus Fraxi', the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (1877), the Centuria Librorum Absconditorum (1879) and the Catena Librorum Tacendorum (1885),

Who Knocked the Phalluses Off Hermes?

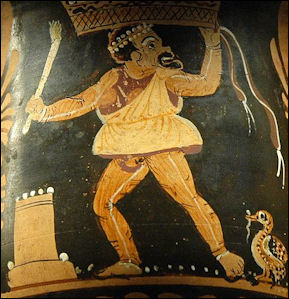

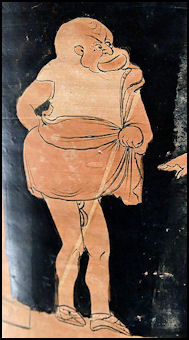

Theater slave During the Peloponnesian War, an group of vandals went around Athens knocking the phalluses off Hermes - the steles with the head and phallus of the God Hermes which were often outside houses. This incident, which lead to suspicions of the Athenian general Alciabiades, provided Thucydides with a spring board to recount the story of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, two homosexual lovers credited by the Athenians with overthrowing tyranny.

Thucydides wrote in “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” 6th. Book (ca. 431 B.C.): “There they found the Salaminia come from Athens for Alcibiades, with orders for him to sail home to answer the charges which the state brought against him, and for certain others of the soldiers who with him were accused of sacrilege in the matter of the mysteries and of the Hermae. For the Athenians, after the departure of the expedition, had continued as active as ever in investigating the facts of the mysteries and of the Hermae, and, instead of testing the informers, in their suspicious temper welcomed all indifferently, arresting and imprisoning the best citizens upon the evidence of rascals, and preferring to sift the matter to the bottom sooner than to let an accused person of good character pass unquestioned, owing to the rascality of the informer. The commons had heard how oppressive the tyranny of Pisistratus and his sons had become before it ended, and further that that had been put down at last, not by themselves and Harmodius, but by the Lacedaemonians, and so were always in fear and took everything suspiciously. [Source: Thucydides, “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” 6th. Book, ca. 431 B.C., translated by Richard Crawley]

In a review of Debra Hamel’s “The Mutilation of the Herms: Unpacking an Ancient Mystery,” Carolyn Swan of Brown University wrote in the Bryn Mawr Classical Review: “The ancient Greek herm—a semi-iconic statue, consisting of a rectangular stone pillar topped by the bearded head of Hermes and sporting an erect phallus (carved in relief or in-the-round)—is unquestionably an unusual sculptural type, and one that has never been treated in a particularly thorough or satisfactory manner. Likewise, the sudden and wide-scale mutilation of the Athenian herms in 415 B.C. is an event that remains puzzling despite the contemporary literary accounts that survive. Debra Hamel rightly draws attention to the ongoing obscurity of the event in this slim, self-published volume; she uses the event as a case study to illustrate both the principles and limitations of Classical scholarship to a non-Classicist and student audience. In seventeen short chapters—each chapter consisting of one to three pages of text, for a total of about 40 pages—Hamel presents the reader with an overview of the events of 415 B.C., identifies the men who were involved, and comments on the nature of their individual testimonies. [Source: Carolyn Swan, The Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University, Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2012.12.40]

“In her introductory chapter, Hamel gives a brief overview of the facts: one morning in the spring of 415 B.C. it was discovered that the herms dotting the urban landscape of Athens had been vandalized, which launched an investigation into impious acts and caused many Athenians to flee or be put to death. In the second chapter (“How Were the Herms Damaged?”), Hamel highlights the evidence for the manner in which the herms were actually vandalized. Although contemporary sources like Thucydides refer to the damage of faces (prosopa) specifically, Hamel speculates it is unlikely that the damage ended there. She points primarily to the references in Aristophanes’ 411 B.C. comedy Lysistrata (lines 1093-1094) that warns the ithyphallic characters in the play of the dangerous hermokopidai (“herm-choppers”), and thus Hamel suggests it would be reasonable to conclude that the phalloi of the statues did not escape the attention of the vandals.

“The third chapter (“The Sicilian Expedition”) identifies the Peloponnesian War and the Athenians’ planned naval attack on Sicily as the main social and historical context of the events under consideration. Hamel observes that the mutilation of the herms had a major impact on the Sicilian expedition—regardless of whether or not this outcome was the intention of the vandals. The Eleusinian Mysteries are introduced in Chapter Four (“The Mysteries”) as an integral part of the larger story. After the mutilated herms were discovered, a commission of inquiry was established to investigate the crime and rewards were offered for information about any sacrilegious acts (not just the desecration of the herms). Most importantly, Alcibiades—one of the three Athenian generals appointed to command the Sicilian expedition—was implicated in profanation of the Mysteries.

“The following four chapters make up a chronological discussion of the various witnesses who came forward and their testimonies about the mutilation of the herms and the profanation of the Mysteries. Chapter 5 (“Andromachus’ Testimony”) presents the first of these witnesses, a slave who implicated Alcibiades and ten other men in the profanation of the Mysteries, while Chapter 6 (“Alcibiades and the Departure of the Fleet”) describes Alcibiades’ reluctance to depart for Sicily before the charges brought against him were actually addressed in trial. Chapter 7 (“Teucer, Agariste, Lydus, and Leogoras”) outlines several testimonies that took place after Alcibiades’ departure, which included information about both the herms and the Mysteries. Chapter 8 (“Diocleides’ Story”) outlines an interesting but probably false eyewitness account of the herm mutilation; Chapter 9 suggests why the story of Diocleides was particularly believable, introducing to the reader the role of social clubs (hetaireiai) and drinking parties (symposia) in Athenian society.

“In the next three chapters, Hamel draws attention to the fact that the main source of evidence we have for the information presented during the inquiry comes from a speech given by Andocides ca. 400/399 B.C., when he himself was accused of profanation. Chapter 10 (“Andocides’ On the Mysteries”) introduces the circumstances of his trial and makes the point that Andocides was likely not an impartial reporter of the events of 415 B.C. Chapter 11 (“Andocides’ Story”) and Chapter 12 (“Was Andocides Guilty?”) are two of the slightly longer chapters of the book, describing in somewhat more detail the testimony of Andocides and its effect on the outcome of the inquiry, and considering whether he was lying about his own involvement in the impieties. Hamel wraps up her discussion of the evidence in Chapter 13 (“Case Closed”) by noting that Andocides’ confession largely ended the matter in the minds of the Athenians. She also acknowledges that most modern scholars accept the conclusion that members of a hetaireia were responsible for the mutilation of the herms, likely as a pledge of group trust (pistis). “

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024