Home | Category: Religion / People, Marriage and Society

FUNERALS IN ANCIENT GREECE

The Greeks believed that dying unmourned was worse than death itself. Funerals were often elaborate and expensive. The body was usually anointed and wrapped in a shroud by the women in the family, then placed in a bier and carried through town. Emotional outpourings were expected and often families hired mourners to create as big a spectacle as possible. The practice later got to be so out of hand in Rome that professional mourners were banned.[Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

The funeral usually took place in the early morning before sunrise, and throughout the whole of antiquity both burying and burning were common, sometimes subsisting side by side, while at other times one fashion or the other was more general. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Round about stood the mourners, who called aloud many times on the dead, bidding him farewell. There do not appear to have been any other ceremonies connected with the funeral, nor did it bear a specially religious character, such as would be given it by the presence of priests or the offering of sacrifices; still, we must not forget that the mere act of burying or burning was regarded as a religious one. Funeral orations were only pronounced in the case of soldiers who had fallen in war, or men who had deserved specially well of their country.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Greek Way of Death” by Robert Garland (1985) Amazon.com;

“Greek Burial Customs” by Donna Kurtz (1978); Amazon.com;

“Birth, Death, and Motherhood in Classical Greece” by Nancy Demand (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Burial Customs of the Ancient Greeks” by Frank Pierrepont Graves (1869-1956) Amazon.com;

“Mortuary Variability and Social Diversity in Ancient Greece: Studies on Ancient Greek Death and Burial” by Nikolas Dimakis and Tamara M. Dijkstra (2020) Amazon.com;

“Death in the Greek World: From Homer to the Classical Age” by Maria Serena Mirto and A.M. Osborne (2012) Amazon.com;

“Vergina: the Royal Tombs” by Manolis Andronicus (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Furniture and Furnishings of Ancient Greek Houses and Tombs”

by Dimitra Andrianou (2009) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Necromancy” by Daniel Ogden (2004) Amazon.com;

“Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece” by Sarah Iles Johnston (1999) Amazon.com;

“Underworld Gods in Ancient Greek Religion” by Ellie Mackin Roberts (2022) Amazon.com;

“Greek & Roman Hell: Visions, Tours and Descriptions of the Infernal Otherworld” by Eileen Gardiner, Homer, Hesiod, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife” by Bart D. Ehrman Amazon.com ;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

Caring for the Dead in Ancient Greece

There were a number of customs connected with death and burial, which were partly due to the belief that the soul would be more easily received and allowed to remain in the dark realm of shadows in consequence of this care of the body; but the ancients also regarded fitting burial and care for the grave as the fulfilment of a duty imposed by the gods, and likely also to bring blessing to the surviving members of the race. This duty was, therefore, only neglected in the very rarest cases. Criminals were buried without any ceremony, or were left to rot unburied; suicides, too, were refused the common honours of public burial, and were put away by night, a time which was not customary for funerals. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The Greeks and Romans were not exactly sure what the relationship was between a dead person's body and his soul. To made sure that they body was well taken care of, just in case the soul continued to linger in the body for a while, families of the deceased often stuck a long straw into the tomb and occasionally poured down food and drink to the dead. For important people, sometimes funerary games were held. They were described in the “ Iliad”. In the early days large feast were often held on the death days of important heroes.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The deceased was... prepared for burial according to the time-honored rituals. Ancient literary sources emphasize the necessity of a proper burial and refer to the omission of burial rites as an insult to human dignity (Iliad, 23.71). Relatives of the deceased, primarily women, conducted the elaborate burial rituals that were customarily of three parts: the prothesis (laying out of the body), the ekphora (funeral procession), and the interment of the body or cremated remains of the deceased. After being washed and anointed with oil, the body was dressed and placed on a high bed within the house. . [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Care of Deceased After Death in Ancient Greece

Lets image what happens after the last breaths of a well-to-do Athenian surrounded by his family — A family member steps up to the bed, uncovers the face of the dead man, and softly closes his eyes and mouth. According to the curious ancient belief, not peculiar to the Greeks, that a human being is unclean immediately after entrance into life, and also on his departure from the world, and as this uncleanness is extended to the whole house and all who associate with it, immediately after the death a vessel of consecrated water, which must be brought from another house, is placed before the door, and everyone who leaves the dwelling sprinkles himself from it, in order to be once more pure and able to associate with others. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The corpse is then washed by the women of the family, anointed with fine oil and sweet-scented essences, and clothed in pure white garments. These are the dress of common life — the chiton and the himation, but so put on that both arms are covered and only the head and feet seen. Youths were probably clad in the chlamys, and the Spartans preferred to clothe their dead in the scarlet military cloak, while at Athens coloured garments were sometimes used instead of white. On the dead man’s head they put a wreath of real flowers — whatever the season might supply — or else laurel, olive, or ivy. At burial, this was often replaced by an artificial wreath of beaten gold leaf, and numerous remains of these death-wreaths, which were often of very artistic workmanship, have been found in Greek graves. Relations and friends also sent fresh wreaths and garlands as a token of sympathy, and these were used for decking the bier and grave.

In the dead man’s mouth they put a coin, as passage money for the ferryman who had to ferry the souls over the Styx; for after the belief in Charon, which was unknown in the Homeric period, had taken firm root among the Greeks, it was regarded as a pious duty to supply the dead man, as soon as possible, with this passage money, in order that the shade might not wander too long restlessly by the shore of Styx. The coin was put in his mouth, because in common life it was not unusual to put single coins in the hollow of the cheek, since pockets were unknown in ancient costume; large sums were seldom carried about, or else they were put in a bag. It was a similar superstition which made people in some places put a honey-cake by the side of the corpse to pacify the dog Cerberus, the fierce guardian of the lower regions.

Bodies buried with coins in their mouths presumably as payment to the ferryman of the underworld were found in an excavation of Boulevard de Port-Royal in Paris, in 2023. The burials were from a large necropolis and dated the A.D. 2nd century. Archaeologists also unearthed skeletons dating to the same period along with artifacts and a a pig's skeleton.[Source: Katherine Tangalakis Lippert, Business Insider, November 23, 2023]

Laying Out of the Body in Ancient Greece

Before the funeral there was a solemn laying-out of the body (prothesis), when friends and acquaintances came to see the departed for the last time, and the near relations took part in the funeral lament for the dead. This laying-out usually took place in the central hall of the house, but care was taken that the sun should not shine on the corpse, since even the Sun god must not pollute himself by the sight of a dead body. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

On a couch covered with cushions and hangings, adorned with flowers and branches, the dead man was laid, his feet turned towards the house door, through which he must take his last journey; round about him, at any rate at Athens, they placed large or small oil flasks (λήκυθοι), adorned with paintings, all depicting scenes dealing with death or graves, which were made in one of the Attic vase factories specially for this purpose, and were probably sent by sympathetic friends as funeral offerings.

We find the laying-out of the corpse represented on a great many vase paintings. Here we see the dead man lying on a richly-decked couch, in front of which stands a footstool; he is enveloped in his mantle up to his neck, he wears a wreath, and his head rests on several cushions. In front of the couch and at the sides stand six women, all raising their arms with gestures of grief; some of them are touching their heads, as though to tear out their hair. A little girl in a similar attitude stands at the foot of the bed; on the right, turning away from the scene, stands a boy.

The hot climate of the south generally necessitated limiting the duration of this ceremony to a single day, and, indeed, Solon expressly commanded that this should be done; only where special measures were taken for preserving the body was it possible to leave it for several days. Embalming was not customary in Greece; it was only when the corpses of those who had died in foreign lands were brought home to be buried, that they were placed in some substance to check the dissolution — for instance, in honey, as the Spartans did with those of their kings who died away from home.

Funeral Laments in Ancient Greece

Funeral laments for the dead were intoned before, during and after the funeral. Besides the nearest relations, intimate friends also took part in the solemn funeral laments before the funeral, , and were sometimes specially invited for the purpose. The servants of the house also stood by the couch with the other mourners, and joined with them in the lament, in which men and women, standing apart, joined alternately. This lament was no wild, irregular wail, but a regular hymn of sorrow, and very often singers were specially hired in order to add to the beauty of the performance, and the hymn was sometimes broken from time to time by choruses sung either by the whole assembly or by semi-choruses. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Many external marks of sorrow were also shown, such as are customary in the south, where the character of the people is more violent and excitable, such as beating the breast, lacerating the cheeks, tearing out the hair, rending the garments; and sometimes cries of grief interrupted the song of mourning. Solon had ordered moderation in these marks of sorrow, but it must have been difficult, if not impossible, to keep within bounds by any legal decrees the expression of wild despair, especially on the part of the women.

Lamentation of the dead is featured in early Greek art at least as early as the Geometric period, when vases were decorated with scenes portraying the deceased surrounded by mourners. We find it universally adopted in the Homeric period, and here, too, in the form of responsions; the wail is heard at Troy by the corpse of Hector, as well as in the Greek camp by the bier of Achilles. We find the funeral lament represented on a great many vase paintings. Here we see under the dead man’s couch his shield, helmet, and cuirass; of the wailing women, who are almost all tearing out their hair, one holds a lyre in her hand, and another a fillet; the former is accompanying the lament, the other is about to deck the corpse or the bier.

Funeral Rituals in Ancient Greece

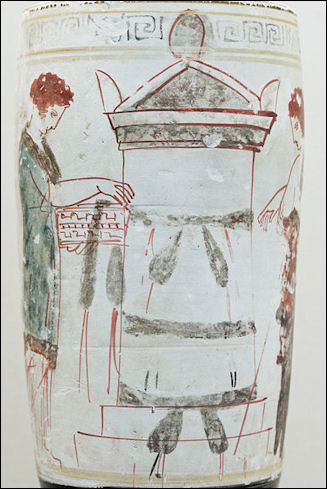

There were special cults that had special rites for the dead. In most cases these cults were very secretive and no information about their rituals or even the cults themselves has survived. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Following the prothesis, the deceased was brought to the cemetery in a procession, the ekphora, which usually took place just before dawn. Very few objects were actually placed in the grave, but monumental earth mounds, rectangular built tombs, and elaborate marble stelai and statues were often erected to mark the grave and to ensure that the deceased would not be forgotten. Immortality lay in the continued remembrance of the dead by the living. From depictions on white-ground lekythoi, we know that the women of Classical Athens made regular visits to the grave with offerings that included small cakes and libations.” [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

On the sacrifice of a bull at funeral ceremony, Plutarch wrote in “Life of Aristides” (c. A.D. 110): “And the Plataeans undertook to make funeral offerings annually for the Hellenes who had fallen in battle and lay buried there. And this they do yet unto this day, after the following manner. On the sixteenth of the month Maimacterion (which is the Boiotian Alakomenius), they celebrate a procession. [Source: Plutarch, “Plutarch’s Lives,” translated by John Dryden, (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910)

“This is led forth at break of day by a trumpeter sounding the signal for battle; wagons follow filled with myrtle-wreaths, then comes a black bull, then free-born youths carrying libations of wine and milk in jars, and pitchers of oil and myrrh (no slave may put hand to any part of that ministration, because the men thus honored died for freedom); and following all, the chief magistrate of Plataea, who may not at other times touch iron or put on any other raiment than white, at this time is robed in a purple tunic, carries on high a water-jar from the city's archive chamber.

He proceeds, sword in hand, through the midst of the city to the graves; there he takes water from the sacred spring, washes off with his own hands the gravestones, and anoints them with myrrh; then he slaughters the bull at the funeral pyre, and, with prayers to Zeus and Hermes Terrestrial, summons the brave men who died for Hellas to come to the banquet and its copious drafts of blood; next he mixes a mixer of wine, drinks, and then pours a libation from it, saying these words: "I drink to the men who died for the freedom of the Hellenes."

Funeral Procession in Ancient Greece

Whether an individual was buried or cremated, the solemn funeral procession (ekphora) was never omitted; the crematoria, like the cemeteries, were outside the city gates, since at Athens, and probably in most Greek states, they were not allowed to bury their dead within the walls; the Doric states alone seem to have made an exception to this rule. A very ancient painted vase seems to afford a proof that it was customary in early times to convey the dead to the cemetery on a car drawn by horses, but in the historical age, at any rate, the corpse was taken to the grave on the same couch on which it had been exposed to view. This duty was generally performed by the slaves of the household, and where there were not sufficient of these, gravediggers were specially hired; while in the case of men who had deserved well of their country, the citizens regarded it as an honour to perform this duty themselves. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

If the dead man had died a violent death, a spear was carried in front of him, which pointed to the revenge to be taken; the spear was then fixed in the earth near the grave, and the nearest relation pronounced a curse against the murderer, after which the place was watched for three days. This did not, however, point to revenge on the part of the relations alone, but to the punishment to be inflicted by the legal authorities. As a rule, the male relations and friends walked at the head of the processions, and the women behind the corpse; but one of Solon’s ordinances limited the female followers to the nearest relations not extending beyond the nieces. Among the more distant relations, only women over sixty years of age were allowed to follow. This law does not, however, seem to have been quite strictly observed.

All the mourners wore grey or black mourning; the nearest relations cut their hair off, for the custom of shaving the hair in case of death is a very old one, and even in Homer we read that the hair cut off was sometimes placed in the dead man’s hand. During the procession laments were again sung, and accompanied by the wailing tones of a flute; but here customs differed somewhat, and at Ceos, for instance, where the ordinances concerning burial, differing in many respects from the Attic customs, have been preserved to us, there were especial directions that the body should be carried out in silence. The dead man wore the clothes in which he had been laid out, but extravagance and excessive luxury necessitated some limitations by the law, so that Solon expressly ordained that the number of garments should not exceed three, and the above-mentioned ordinance allowed only one under garment, one cloak, and one pall or covering, the whole value not to exceed 300 drachmae, and also ordained that the couch on which the dead man was carried to the grave, and the other hangings or cushions, should not be burnt or buried, but brought back again.

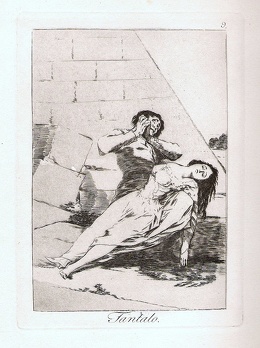

prothesis (lying in state of a body) attended by family members, with the women ritually tearing their hair

Burial and Cremation in Ancient Greece

The dead were mostly buried in the Earth in jars or coffins. The word coffin come from the Greek word “ kophinos”, meaning "basket." Greek graveyards have been found with newborns buried between clay roof tiles. Cremations were usually reserved for adults, although they were sometimes performed on children. Sometimes relatives of the deceased sucked down wine from a decorated bowl and then tossed the bowl into the cremation fire. In Ptolemaic Egypt the dead were sometimes mummified.

It seems as though burying had at first been more common among the Greeks than cremation. It is true we find only burning mentioned in the Homeric poems, but we must not forget that we are concerned with exceptional circumstances in the Iliad, since the warriors who fell before Troy did not die at home; and in such cases, even in later times, burning was preferred, since it enabled the survivors to bring the ashes of the dead man home with them. Still, even in those early times, burying was very common, as is proved, in spite of the lack of literary evidence, by the ancient burial grounds discovered at many places in Greece; and similarly, in the historic period, the burning of dead bodies, though certainly practised, was not so common as burying, if only for the very practical reason that the latter was far cheaper and much less troublesome. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

There were various ways of burying the dead. If they were placed in a grave it was customary to make use of a coffin, which was let down into the grave by the bearers. We see this represented on the vase picture, with two men, who look like barbarian slaves or men of the lower classes, are standing in the grave and holding up their hands in order to receive the coffin, which is carefully let down by two men of similar appearance; on the right and left stand weeping women. The coffins were sometimes made of wood, especially Cyprus wood, which was occasionally decorated with costly carving and painting; sometimes of clay, less often of stone, although stone sarcophagi have been found in Greece, but the custom of decorating their sides with sculptured pictures did not become common until the Roman period. The shapes of the coffins differed; there were square box-like coffins, and also others of an oval shape, or pointed coffins, made of flat terra-cotta tiles. Poor people were generally buried in some common cemetery, in simple coffins, and in graves made to hold a large number.

During a cremation, when the corpse was consumed by the fire and the pile had burned down, the glowing remains were quenched with water or wine. This act is represented on a vase painting, which gives a scene from the Apotheosis of Hercules. The ashes and pieces of bone which had not been completely consumed were then collected and put in a special vessel. For this purpose they used urns, coffin-like boxes, and small vessels, which were afterwards placed in larger cases. These were constructed of different materials, clay or stone, brass, lead, sometimes even silver or gold. The urns were then placed, like the coffins, in a vault or under the earth.

According to Live Science: The ancient Greeks colonized Kamarina, a city-state in southeastern Sicily, in 598 B.C., and remained there until the middle of the first century A.D., Inhabitants used the city's necropolis, called Passo Marinaro, from the fifth to the third centuries B.C. About 85 percent of the burials in Passo Marinaro contain intact skeletons that are either lying flat on their backs or on their sides with bent knees, according to reports from Giovanni Di Stefano, one of the site's principal excavators during the 1980s. The remaining 15 percent of the burials are cremations, and about half of the graves contain artifacts, such as terracotta vases, figurines and coins. [Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, June 25, 2015]

Burial Goods in Ancient Greece

The custom of placing various objects required in daily life in the grave by the side of the dead man was universal, chiefly the things with which he had been occupied in his lifetime, or which belonged to his profession; clothes, money, oil-flasks, and other vases were put in, and besides them, in the case of a child, his toys; in the case of a warrior his arms; a woman’s spindle or ornaments and mirror; a young man’s strigil and oil-flask; a musician’s flute or lyre. We owe nearly all the small art treasures which have come down to us from antiquity, such as vases, terra-cottas, cameos, gold ornaments, caskets, etc., to this custom of adorning the graves of the dead with the objects used in daily life. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Many of these, especially vases, lamps, candlesticks, arms, etc., seem to have been specially made with a view to being placed in the grave, since they were often of no use for practical purposes. There were no doubt special places outside the walls devoted to burning the bodies, though it is quite possible that some people were burnt on their own land if that happened to be large enough. Wood, twigs, and other easily-combustible substances were used for erecting a pile; the body was laid on it, along with the cushions destined to be burnt, among which, besides the objects already mentioned, the favorite animals of the dead were often included; and the pile was lighted with a torch.

Sometimes Greeks were buried with bronze nutcrackers and boat-shaped gold earrings, bottles of perfume, and ivory dolls. Some soldiers were buried wearing a helmet and a golden mask. To deter the ghost of a suicide victim ancient Athenians severed the hand and buried it apart from the body.

After the Funeral in Ancient Greece

Visiting a grave When the burying or burning was ended, it was the custom for the relations and intimate friends of the deceased to return to the house of the latter, and after both the house and its inhabitants had been purified from the pollution connected with the death, by means of incense and sprinkling, or washing with consecrated water, they took part together in a funeral banquet. At this the near relations, who had hitherto refrained from food, or at any rate from meat, for the first time again partook of it, a custom which could probably only be carried out when the funeral took place on the second day after the death. On the third and ninth days after, the nearest relations went to the grave with libations, which consisted in part of bloodless offerings, such as milk, honey, wine, etc., and partly in the sacrifice of real victims. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Graves were often decorated with wreaths, fillets and growing plants. These were often renewed, and especially on the anniversaries of birth and death the relations came with libations and sacrifices, pouring out sweet odours or wine, or by other means showed that the memory of the departed was not gone from them. There are many pictures extant, especially on vases, depicting the care of the graves. One vase painting shows two women approaching a stele, carrying plates with flasks and fillets. Similarly, the weeping woman at the end of the stele is drawn with especially beautiful grace.

Thus the Greeks held the memory of their dead worthily in honour, although their time of mourning did not last nearly as long as is customary with us, but was generally limited to one or a few months. Even in the case of those who had died away from home, and whose remains could not be brought back, as, for instance, those who were drowned at sea, or altogether lost to sight, they erected cenotaphs, in order to have some spot with which to connect the ceremonies devoted to the memory of the dead. The tombstone was probably that of a man who had lost his life in some such way, perhaps in a shipwreck. The relief shows the dead man sitting sadly on land near his ship, and gazing towards his distant home which he was not permitted to see again. In the empty space below, his name and probably also the details of his death were inscribed in writing, which has now been effaced.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except mass grave from Archaeology magazine

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024