Home | Category: First Hominins in Europe / First Modern Humans

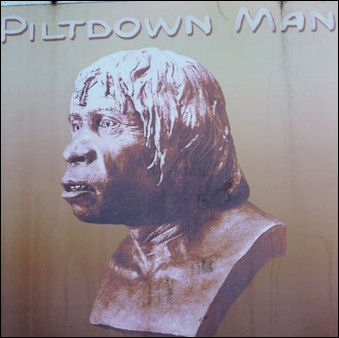

PILTDOWN MAN

One of the most famous hoaxes of all time involved the discovery of a “missing link” called Piltdown man. In 1912 an English attorney and amateur geologist, named of Charles Dawson (1864-1916) found some bone fragments while looking for road mending material in a gravel pit near Piltsdown Common in East Sussex,in southeastern England. Dawson notified Arthur Woodward Smith, a distinguished paleontologist, who launched a major excavation that yielded a skull with a big brain cavity, canine teeth and high forehead. It was hailed as the "missing link" between humans and apes and held up as proof of Darwin's theory of evolution. After the find the New York Times ran the headline "Darwin Theory is Proved True."

One of the most famous hoaxes of all time involved the discovery of a “missing link” called Piltdown man. In 1912 an English attorney and amateur geologist, named of Charles Dawson (1864-1916) found some bone fragments while looking for road mending material in a gravel pit near Piltsdown Common in East Sussex,in southeastern England. Dawson notified Arthur Woodward Smith, a distinguished paleontologist, who launched a major excavation that yielded a skull with a big brain cavity, canine teeth and high forehead. It was hailed as the "missing link" between humans and apes and held up as proof of Darwin's theory of evolution. After the find the New York Times ran the headline "Darwin Theory is Proved True."

In 1953, over 40 years, after the “discovery” was made, Piltsdown Man was revealed as a hoax. The skull it turned out belonged to an 19th century modern man. It had been stained and "aged" with salt and fitted with doctored up orangutan jaw. Th person who doctored the bones and planted them in the pit was nver determined. Suspects include Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who lived near the pit; Pieree Teillard de Chardin, a famous scholar who participated in the dig and was surprisingly unsurprised when the hoax was revealed (there was also some incriminating evidence letters he wrote); Sir Arthur Kieth, an anthropologist who had the expertise to make the fakes and a motive (the skull helped prove his theories); Lewis Abbott, a Sussex jeweler and counterfeiter, with a history of fraudulent claims; and Dawson himself, the discover of the bones.

In 1996, two British researchers accused Martin A.C. Hinton, a curator of zoology at the Natural History Museum. Their evidence were bones found in a trunk with Hinton's initials that were stained in same way as the Piltsdown skull. Famous for his practical jokes, Hinton held a grudge against Woodward Smith over a pay dispute.

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Clan of the Cave Bear: Earth's Children, Book One” by Jean M. Auel Amazon.com

"Piltdown Man Hoax: Case Closed” by Miles Russell Amazon.com;

Exposing the Piltdown’s Man Forgery

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: Doubts dogged Piltdown Man, primarily because the bones didn’t appear to fit with later finds in Africa and Asia. In 1953, Kenneth Oakley, a scientist at the museum, confirmed suspicions and exposed Piltdown Man as a fraud. The jawbone was probably from an orangutan and the skull from a modern human, he found, and they had been manipulated and stained. There have been a number of suspects over the years, in varying conspiratorial combinations. Suspicion usually falls on four: Dawson, Woodward, Teilhard de Chardin (a Jesuit priest who uncovered the canine tooth), and Martin Hinton (a museum volunteer later found to have, among his effects, stained and modified bones). [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2016]

Now the testimony of a multidisciplinary group of scientists who revisited the Piltdown finds with the latest in spectroscopic, radiographic, and genetic technology has placed the spotlight on a single culprit. Their work shows that the Piltdown I and II finds carry the same modus operandi of staining and modification, and that the tooth from Piltdown II likely came from the jawbone from Piltdown I.

“The science showed us these hominin specimens are all connected,” says Isabelle De Groote, a paleoanthropologist from Liverpool John Moores University. “They carry the signature of a single forger.” There is only one person associated with the finds at Piltdown II, one man with means, motive, and opportunity to commit the infamous hoax: Charles Dawson. “The tie-up of Piltdown I and II means that it is more than circumstantial,” Stringer says. “I think we can show with a very high degree of certainty that he possessed the orangutan jawbone that created the fakes at both sites. It’s got to be him.”

Charles Dawson — Perpetrator of the Piltdown’s Many Forgery

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “In February 1912, amateur fossil collector Charles Dawson wrote to Arthur Smith Woodward, distinguished Keeper of Geology at the British Museum of Natural History (now just the Natural History Museum), to tell him of a new find, “a thick portion of a human(?) skull.” The previous decades had seen the identification of Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, and scientists and antiquarians were on the hunt for more — specifically human ancestors with apelike features and bigger, humanlike brains. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2016]

Two years of excavation at the site of Dawson’s find, Piltdown, Sussex, yielded a simian jawbone with two molars, a canine tooth, parts of a humanlike skull, stone tools, and mammal fossils. Surely the find, named Eanthropus dawsonii (“Dawson’s dawn man”), would be Dawson’s long-coveted ticket into the Royal Society. “People wanted to believe it,” says Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum, who recalls seeing the Piltdown finds on display as a child in the 1950s. “Britain was ready for Piltdown Man.” Dawson died in 1916, but not before he wrote to Woodward of another find, at a site known as Piltdown II, of a tooth and more animal fossils, which Dawson’s wife turned over to the museum.

“Dawson was an experienced fossil collector who wrote or coauthored more than 50 scientific publications. He knew precisely what would excite the scientific world and how to obtain bone samples. He was also not reserved in his ambition, having written to Woodward in 1909, “I have been waiting for the big ‘find’ which never seems to come along.” Says Stringer, “Dawson got tired of waiting and decided to help things along.” He also had a history of faking discoveries, including inscribed Roman bricks. These new finds appear to acquit Woodward of fraud, but not of a surfeit of naïveté and a lack of scientific scrutiny. With his work on fossil fish long having been overshadowed by his connection to the fraud, he leaves a lesson for us: Healthy science relies on healthy skepticism.

Bogus Paintings and Dubious Leakey Discoveries

In the 1990s a bogus cave painting site called The Ardéche in the Basque area of Spain fooled many people. The French cultural minister, said the "engravings showed the natural degradation of age. Some were covered with very old calcite deposits.” The site was revealed to be what it was when fragments of a sponge were found under one painting.[Source: Marlise Simons, New York Times, January 24, 1994]

Louis Leakey is arguably the most famous paleontologist and hominin scientist of all time. But Many of Leakey’s later “discoveries” were dubious at best. In the 1960s he claimed that 20-million -year-old apes bone he unearthed were the oldest hominin fossils every found and made similar claims about some 14-million -year-old ape bones he named “Kenyapithecus wickeri”. His most outlandish claim came in 1967 when he announced at a scientific meeting that a lump of lava he found near Lake Victoria was a tool used “Kenyapithecus wickeri”. The announcement was so out of the realm of what was possible not a single question as asked. Equally outrageous was his claim that stone flakes found in the Calico Hill outside Los Angeles were 100,000 years old. The prevailing view then as it now is that humans didn’t arrive in the Americas until 30,000 years ago at the earliest.

Prehistoric Man Novels, Films and Television Shows

The Bear Clan series — “The Clan of the Cave Bear,” “The Valley of the Horses” , “The Mammoth Hunters” , “The Plains of Passage” , “and The Shelters of Stone” — were written by Jean Auel, a former circuit board designer from Oregon, about Ayla, a 30,000-year-old early human woman who ends up with a band of Neanderthals. More than 40 million people have read the books, which have been translated into 27 languages. In the film version of “The Clan of the Cave Bear” Daryl Hanna played Ayla.

The Bear Clan series — “The Clan of the Cave Bear,” “The Valley of the Horses” , “The Mammoth Hunters” , “The Plains of Passage” , “and The Shelters of Stone” — were written by Jean Auel, a former circuit board designer from Oregon, about Ayla, a 30,000-year-old early human woman who ends up with a band of Neanderthals. More than 40 million people have read the books, which have been translated into 27 languages. In the film version of “The Clan of the Cave Bear” Daryl Hanna played Ayla.

Auel is a big, grandmotherly-looking woman Even though she is not trained as a writer or scientist she has won the admiration of archaeologists for here her research. She has toured many archaeological sites in Europe and once slept in a snow cave under a tanned buckskin to get a sense of what life was like for her characters.

Prehistoric thrillers include “Neanderthal” by John Darnton and “Almost Adam” by Petru Popescu. William Golding’s “The Inheritors” was described by the New York Times as the best of the Neanderthal novels. In “Ember from the Sun” by Mark Canter a Neanderthal born from a human womb emerges with magical powers. In Jasper Forde’s “Thursday next” the Neanderthals can read minds.

H.G. Wells wrote a novel, “The Grisly Folk” , in 1921 about an encounter between a Neanderthal and a modern human that was often violent and helped shape the early impression people had of Neanderthals. “The legends of ogres and man-eating giants, that haunt the childhood of the world,” he wrote,” may descend to us from those ancient days of fear.”

The film “10,000 B.C. “ (2008), directed by Roland Emmerich, was a disappointment. The monsters and the story were pretty hokey. Some have even said that the camp, cult classic “One Million years B.C.” — which featured dinosaurs and prehistoric man living together and catapulted Raquel Welch to fame — was better.

The insurance company Geico ran a series of advertisements in the United States with a group of cavemen living in the modern world that many people thought was very funny. The ads helped Geico’s market share of the insurance business to jump from no. 6 position to no. 4. The ads were so popular they generated a spin off television show.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024