ANCIENT GREEK CURSES

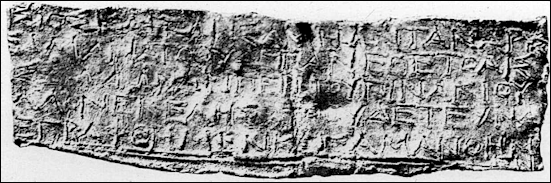

ancient Greek binding spell from the 4th century BC

The ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Greeks, Romans, Persians, Jews, Christians, Gauls and Britons all dispensed curse tablets used placate "unquiet" graves, cast love spells and call up the spirits of the Underworld to make trouble. [Source: Christopher A. Faraone, Archaeology, March/April 2003]

Curse objects were used to call ghosts from the Underworld to bring suffering on one's enemies. They were often buried with the dead who were believed to have the power to pass them on to a party that could carry them out. Curses buried with people who died young were thought to be able to reach their destination quicker. Curses became such an annoyance in Athens they were outlawed. Even so they were secretly buried on the dead.

It is not clear what kinds of punishments there were if one was caught putting a curse on someone. One of Plato’s dialogues asserts that “if it be held that a man is acting like an injurer by these of spells, incantations or any such mode of poisoning, if he be a prophet or diviner, he shall be put death.” In this passage Plato’s character thinks that practitioners of black magic should be punished but in Greek and Roman law investigations of magic was only done if it was involved in a serious crime such as murder.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World” by John G. Gager (1999) Amazon.com;

“Votive Body Parts in Greek and Roman Religion” by Jessica Hughes (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Love Magic” by Christopher A. Faraone (2001) Amazon.com;

“Superstitious Beliefs And Practices Of The Greeks And Romans” by William Reginald Halliday (1886-1966) Amazon.com;

"Amulets and Superstitions: the Original Texts With Translations and Descriptions of a Long Series of Egyptian, Sumerian, Assyrian, Hebrew, Christian, ... With Chapters on the Evil Eye” by E A Wallis Budge (1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune” by Chris Brennan (2017) Amazon.com;

“Magic in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Lindsay C. Watson Amazon.com;

“Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion” by Christopher A. Faraone and Dirk Obbink (1997) Amazon.com;

Magic, Witchcraft and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook

by Daniel Ogden | Apr 24, 2009 Amazon.com;

“Ancient Magic: A Practitioner's Guide to the Supernatural in Greece and Rome” by Philip Matyszak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition”

by Peter Kingsley (1997) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Egyptian Magical Formularies: Text and Translation, Vol. 1"

by Christopher A. Faraone and Sofía Torallas Tovar (2022) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Necromancy” by Daniel Ogden (2004) Amazon.com;

“Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: a Collection of Ancient Texts” by Georg Luck (1985) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek Voodoo Dolls

Archaeologists have found ancient Greek "voodoo dolls" called “ kolossoi”, consisting of a small doll lying in a lead coffin. One such doll had its arms pulled back and a man's name inscribed on its leg. The man appeared to have been involved with a public trial with eight other men, whose names were inscribed on the coffin lid. Kolossoi figures have been found buried in a cemetery, but not inside graves, perhaps to draw the attention of Hades, god of the Underworld.

In Antinopolis, Egypt, a small effigy of woman, dated to the A.D. 4th century was found kneeling with her feet together and her arms tied behind her back. She is pierced with 13 pins: one in the top of her head, one in the mouth, one in each eye and one in each ear, one each in the solar plexus, vagina and anus, and one in the palm of each hand and in the soles of each foot. The effigy was wrapped in an inscribed table and sealed in a pit.

The doll surprisingly was commissioned by a man who wanted a the victim, a woman, to make live to him. The text of the tablet read: “Lead Ptolemasi, who Aias bore, the daughter of Horigense, to me. Prevent her from eating and drinking until she comes to me. Sarapammon, whom Area bore, and do not allow her to have experience with another man, except me alone. Drag here by her hair, by her guts, until she does not stand aloof from me.”

A magical handbook that has been found, dated to around the same time, has an image of a nearly identical effigy with instructions on where to place it and what to recite when doing so. The idea it seems was to cause the woman anguish so she would have feelings of affection for the man who pieced the doll.

Ancient Greek Curse Tablets

Archaeologists have found hundreds of ancient Greek curse tablets, which the Greeks called “katares” — “curses that bind tight”. A great number of them were focused on sporting competitions or legal contests. “To make such a “binding spell,” Christopher A. Faraone wrote in Archaeology magazine, “one would inscribe the victim’s name and a formula on a lead tablet, fold it up, often pierce it with a nail, and then deposit it in a grave or a well or a fountain, placing it in the realm of ghosts or Underworld divinities who might be asked to enhance the spell.”

Curse inscription Many ancient Greek curse tablets made of lead have been found. By far the most have come from Athens, where they have been found buried in cemeteries, inside sanctuaries and wells and outside theaters. They were purchased by shopowners, potters and tavern owners against rivals. Most were aimed at legal opponents. Some were directed at politicians. Many were accompanied by figures: a soldier with a bent sword a man with his hands tied behind his back, creatures with birdlike heads and pronounced sex organs. Many curses were put on bracelets buried with the dead.

Jessica Lamont, an instructor at John Hopkins University, told live Science: “The way that curse tablets work is that they're meant to be deposited in an underground location," such as a grave or well, Lamont told Live Science. "It's thought that these subterranean places provided a conduit through which the curses could have reached the underworld," and its chthonic (underworld) gods would then do the curse's biddings, Lamont said. The person in a garve containing curse tablets may have had nothing to do with the curses or the targets or initiators of the curse. They may have happened to die at the time when someone wanted to cast curses on others in the same community. At the time when funeral ceremonies are conducted, a grave "would have been accessible, a good access point for someone to deposit these tablets underground and bury them," Lamont said. [Source: Owen Jarus, LiveScience.com, April 6, 2016]

Early curse tablets were filled with spelling and grammar mistakes which has led archaeologists and historians to surmise they were probably inscribed by amateurs, but there are hints of professional sorcerers making spells as early as 400 B.C. A passage from Plato’s “Republic” goes: “And then there are the begging priests and soothsayers, who going to the doors of the wealthy persuade them that...if anyone wants to harm an enemy, whether the enemy is a just or unjust man, they [the priest and soothsayers], at very little expense, will do it with incantations and binding spells, once [they claim] they have persuaded the gods to do their bidding.”

Book: “ Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World” by John Gager, professor or religion at Princeton (Oxford University Press, 1998)

Katadesmoi — Curses Addressed to Underworld Deities

Katadesmoi were "lead tablets inscribed with petitions, or requests, that would be addressed to underworld deities," archaeologist Carrie Sulosky Weaver told Live Science. "Usually, the petitioners wanted to gain an advantage in love or business, and it was understood that the deities would direct the spirits of the dead to fulfill the requests of the living. To ensure that the tablets reached the underworld, they would be placed in or near the graves of the recently deceased during secret nighttime ceremonies." [Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, June 25, 2015]

Researchers have found more than 600 katadesmoi from the ancient Greek culture, including 11 from Passo Marinaro, Sulosky Weaver said. Most are degraded and difficult to translate, but some have lists of names, likely of people who were the targets of curses, she said.

Interestingly, a Greco-Roman text dating from between the second century B.C. and the fifth century A.D. tells petitioners to write with ink on seashells to create katadesmoi. Researchers have found three seashells in the Passo Marinaro graves, but it's unclear whether they were intended to serve as katadesmoi, Sulosky Weaver said.

Magic Curse Pot from Athens

What has been described as a magic curse pot was found in Athens. Dated to 300 B.C., it is made of pottery and chicken bones and stands 11 centimeters (4.3 inches) tall. Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Many cultures, ancient and modern, have imagined magic as a supernatural art performed by specialists who undergo mysterious training. But for the ancient Greeks, magic consisted of a number of common rituals practiced by men and women from all social and economic classes. “The Greeks trafficked heavily in magic,” says historian Jessica Lamont of Yale University. “It was one of the ways they managed competition, vulnerability, and risk.” [Source Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

The most common expression of ancient Greek magic was to curse people perceived as a threat by inscribing their names on lead tablets or pottery vessels, such as this pot dating to 300 B.C., which was found in the corner of a building just outside the Athenian Agora, the city’s commercial center.

On the pot’s exterior are 30 full male and female personal names as well as letters or strokes of letters belonging to an additional 25 names. The vessel was pierced with an iron nail and contained the bones of a young chicken, both clear indications that whoever buried it intended to bring harm to the people named, says Lamont. Because the pot was found in a building where terracotta, bronze, and marble objects were manufactured, Lamont believes that the malediction was motivated by a legal dispute among craftspeople. “I think the high number of names is a big clue that this relates to a court case,” she says. “The idea was not just to curse one litigant, but also all witnesses, supporters, the magistrate — anyone who could affect the case.”

The curse pot also reveals the wide range of people who participated in the Athenian legal system. “There aren’t just elite male citizens named on this pot,” Lamont says. “Through this and other curses, we have access to a much broader section of Greek society. This kind of evidence captures the voices of those, like women and craftspeople, who have slipped through the cracks of history.”

Dodona curse inscription

Texts of Ancient Greek Curse Tablets

A spell from Attica in the 4th century B.C. read: "I bind Kalais, the shop-tavern keeper who is one of my neighbors and his wife, Tahittra and the shop-tavern of the bald man and the shop-tavern of Anthemion and Polon the shop-tavern keeper. Of all of these I bind the soul, the work, the hands, tying and mind: all of these I bind to Hermes the Restrainer."

Another read: "I inscriber Selinonitios and the tongue of Selinontios, twisted to the point of uselessness.” A Hellenistic curse read: "I will tattoo you with pictures of terrible punishments suffered by the most notorious sinners in Hades! I will tattoo you with the white-tusked boar." Curses aimed at unfaithful lovers was common in Hellenistic Greece.

On dealing with the testimonies of three butchers in a court of law one tablet read: “Theagues, the butcher, I bind his tongue, his soul and the speech he is practicing. Pyrrhias: bind his tongue, his soul and the speech he is practicing. I bind the wife of Pyrrhias, her tongue and soul. I also bind Kerkion, the butcher, and Dikimos the butcher, their tongues, their souls and the speeches they are practicing. I bind Kineas, bind his tongue, his soul and the speech he is practicing with Theagenes. And Pherekles. I bind his tongue, his soul and the evidence he gives for Theagenes. All of these (i.e. their names) I bind, I hide, I bury, I nail down. If they lay any counterclaim before the arbitrator or the court let them seem to be of no account, either in word or deed.”

2,400-year-old Curse Tablets Target Tavern Keepers

In 2016, a John Hopkins researcher announced that five 2,400-year-old lead tablets that cursed tavern keepers had been found in a young woman's grave in Athens, Greece. Owen Jarus of Live Science wrote: “Four of the tablets were engraved with curses that invoked the names of "chthonic" (underworld) gods, asking them to target four different husband-and-wife tavern keepers in Athens. The fifth tablet was blank and likely had a spell or incantation recited orally, the words spoken over it. All five tablets were pierced with an iron nail, folded and deposited in the grave. The grave would have provided the tablets a path to such gods, who would then do the curses' biddings, according to ancient beliefs. [Source: Owen Jarus, LiveScience.com, April 6, 2016]

“One of the curses targeted husband-and-wife tavern keepers named Demetrios and Phanagora. The curse targeting them reads in part (translated from Greek): “Cast your hate upon Phanagora and Demetrios and their tavern and their property and their possessions. I will bind my enemy Demetrios, and Phanagora, in blood and in ashes, with all the dead…I will bind you in such a bind, Demetrios, as strong as is possible, and I will smite down a kynotos on [your] tongue."

“The word kynotos literally means "dog's ear," an ancient gambling term that "was the name for the lowest possible throw of dice," Jessica Lamont, an instructor at John Hopkins University who recently completed a doctorate in classics, wrote in an article published recently in the journal Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. The "physical act of hammering a nail into the lead tablet would have ritually echoed this wished-for sentiment," Lamont wrote. “By striking Demetrios' tongue with this condemningly unlucky roll, the curse reveals that local taverns were not just sociable watering holes, but venues ripe for gambling and other unsavory activities in Classical Athens."

“The grave where the five curse tablets were found was excavated in 2003 by archaeologists with Greece's Ephorate for Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities. The grave was located northeast of the Piraeus, the port of Athens. Details of the burial have not yet been published, but Lamont said that excavation reports indicate that it contained the cremated remains of a young woman. Lamont has been studying the curse tablets at the Piraeus Museum, where they are now kept. The writing on the curse tablets is neat and its prose eloquent, suggesting that a professional curse writer created the tablets. "It's very rare that you get something so explicit and lengthy and beautifully written, of course in a very terrible way," Lamont said.

“This curse writer, who probably provided other forms of supernatural services — including charms, spells and incantations — was likely hired by someone who worked in Athens' tavern-keeping industry, according to Lamont. "I think it's likely that the person who commissioned them was probably in the world of the tavern himself or herself," possibly a business rival of the four husband-and-wife tavern keepers, Lamont said.

_4th_Century.jpg)

Magic Pella leaded tablet (katadesmos) 4th Century

Curse Found in Athens Targets a Newlywed’s Vulva

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: Thirty lead tablets recovered from the bottom of a public well at the edge of the Kerameikos necropolis in Athens have been found to record curses cast by Athenians against their rivals some 2,300 years ago. Several of the tablets were folded and pierced with nails, while others were fashioned in the shape of livers or coffins. A particularly scathing malediction condemns an allegedly promiscuous newlywed named Glykera and her vulva. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

“Until the late fourth century B.C., such Athenian curse tablets were usually deposited in tombs. At that point, according to the first-century B.C. Roman author and orator Cicero, the statesman Demetrius of Phaleron instituted a new law restricting elaborate burials and funeral practices. To evade detection by the officers employed to enforce this law, crafty sorcerers seem to have turned to wells as a more secretive venue for their magic rituals. The Greeks believed that water, and in particular groundwater, was a conduit to the streams of the underworld, explains archaeologist Jutta Stroszeck of the German Archaeological Institute in Athens. “Water nymphs protected the water,” she says, “and were thus thought to be capable of directing the curses to the gods of the underworld.”

Translation of the glykera curse tablet: “We curse Glykera the wife of Dion, to the gods of the underworld, so she be punished and her wedding be unfulfilled. I bind down Glykera, the wife of Dion, to Hermes Eriounios of the underworld, her vulva, her debauchery, her vice and everything of the sinful Glykera

Roman-Era Greek Tablet Calls Upon the Jewish God to Curse of Greengrocer

A 1,700-year-old curse tablet, whose contents were revealed in 2011, called upon Iao, the Greek name for Yahweh, god of the Old Testament, to strike down Babylas identified as being a greengrocer. Live Science reported: “A fiery ancient curse inscribed on two sides of a thin lead tablet was meant to afflict, not a king or pharaoh, but a simple greengrocer selling fruits and vegetables in the city of Antioch. Written in Greek, the tablet holding the curse was dropped into a well in Antioch, then one of the Roman Empire’s biggest cities in the East [Source: livescience.com, December 2011]

“The curse calls upon Iao, the Greek name for Yahweh, the god of the Old Testament, to afflict a man named Babylas who is identified as being a greengrocer. The tablet lists his mother’s name as Dionysia, “also known as Hesykhia” it reads. The text was translated by Alexander Hollmann of the University of Washington. The artifact, which is now in the Princeton University Art Museum, was discovered in the 1930s by an archaeological team but had not previously been fully translated. The translation is detailed in the most recent edition of the journal Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. “O thunder-and-lightning-hurling Iao, strike, bind, bind together Babylas the greengrocer,” reads the beginning of one side of the curse tablet. “As you struck the chariot of Pharaoh, so strike his [Babylas’] offensiveness.”

“Hollmann told LiveScience that he has seen curses directed against gladiators and charioteers, among other occupations, but never a greengrocer. “There are other people who are named by occupation in some of the curse tablets, but I haven’t come across a greengrocer before,” he said. The person giving the curse isn’t named, so scientists can only speculate as to what his motives were. “There are curses that relate to love affairs,” Hollmann said. However, “this one doesn’t have that kind of language.”

“The lead curse tablet is very thin and could have been folded up. This side contains a short summary of what the inscription says and would have gone on the outside. It’s possible the curse was the result of a business rivalry or dealing of some sort. “It’s not a bad suggestion that it could be business related or trade related,” said Hollmann, adding that the person doing the cursing could have been a greengrocer himself. If that’s the case it would suggest that vegetable selling in the ancient world could be deeply competitive. “With any kind of tradesman they have their turf, they have their territory, they’re susceptible to business rivalry.”

“The use of Old Testament biblical metaphors initially suggested to Hollmann the curse-writer was Jewish. After studying other ancient magical spells that use the metaphors, he realized that this may not be the case. “I don’t think there’s necessarily any connection with the Jewish community,” he said. “Greek and Roman magic did incorporate Jewish texts sometimes without understanding them very well.” In addition to the use of Iao (Yahweh), and reference to the story of the Exodus, the curse tablet also mentions the story of Egypt’s firstborn. “O thunder—and-lightning-hurling Iao, as you cut down the firstborn of Egypt, cut down his [livestock?] as much as…” (The next part is lost.). “It could simply be that this [the Old Testament] is a powerful text, and magic likes to deal with powerful texts and powerful names,” Hollmann said. “That’s what makes magic work or make[s] people think it works.”

Ancient Greek Love Tablets

A curse that focuses on erotic love found on a potsherd perhaps heated in a ritual read: “Burn, torch the soul of Allous, her female body, her limbs, until she leaves the household of Apollonius. Lay Allous low with fever, with unceasing sickness, lack of appetite, senselessness.”

The text of one Greek curse found rolled up in the mouth of a red-haired mummy found in Eshmunen in Ptolemaic Egypt read: “Aye, lord demain, attract, inflame, destroy, burn, cause her to swoon from love as she is being burnt, inflamed. Goad the tortured soul, the heart of Karosa...until she leaps forth and comes to Apalos...out of passion and love, in this very hour, immediately. Immediately, quickly, quickly...do not allow Karosa herself...to think of her [own] husband, her child, drink, food, but let her come melting for passion and love and intercourse, especially yeaning for the intercourse of Aapalos.”

One tablet addressed to a ghost goes: “Seize Euphemia and lead her to me Theon, loving me with mad desire, and bind her with unloosable shackles, strong ones of adamantine, for the love of me, Theon, and do not allow her to eat, drink, obtain sleep, jest or laugh but make her leap out...and leave behind her father. Mother, brothers, sisters, until she comes to me...Burn her limbs, live, female body, until she comes to me, and not disobeying me.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024