ANCIENT GREEK SACRIFICES

Sacrificial hammer Sacrifices were the principal Greek religious ritual. They were often conducted at outdoor altars at temples to gain favor with the gods. Animals were also often sacrificed at religious festivals and sporting events, with different animals being sacrificed at different events. The spilling of blood during a ritual is believed to have magic powers. The haunch of the animal was often offered to the gods along with prayers, requests or favors, pleas for mercy or protection from harm.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Sacrifices took place within the sanctuary, usually at an altar in front of the temple, with the assembled participants consuming the entrails and meat of the victim. Liquid offerings, or libations, were also commonly made. Religious festivals, literally feast days, filled the year. The four most famous festivals, each with its own procession, athletic competitions, and sacrifices, were held every four years at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia. These Panhellenic festivals were attended by people from all over the Greek-speaking world. Many other festivals were celebrated locally, and in the case of mystery cults, such as the one at Eleusis near Athens, only initiates could participate. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

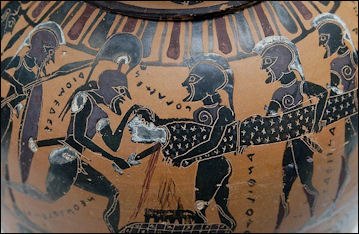

On a vase painting showing a sacrifice a table is shown near an altar; behind it we perceive the antiquated statue of Dionysus, on one side stands a woman with a goat destined for sacrifice, and on the right another woman is approaching carrying a flat dish, probably containing cakes. The offerings represented in two images were probably also destined for Dionysus. A satyr, carrying in his left hand a branch, in his right a dish, probably containing cakes, is approaching an altar, on which similar gifts have already been placed; on the other side, near the table for offerings, on which lie fruit and cakes, a woman, probably a Maenad, is seated, holding in her right hand a branch, in her left a flat basket with little dedicatory offerings. Although these gifts were not immediately destroyed by fire, they were of so transitory a nature that they could not be counted among those destined to be a lasting possession of the gods. The Greeks called these gifts fireless sacrifices. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Smoke Signals for the Gods: Ancient Greek Sacrifice” by F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“Animal Sacrifice in Ancient Greek Religion, Judaism, and Christianity, 100 BC to AD 200" Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Animal Sacrifice: Ancient Victims, Modern Observers”

by Christopher A. Faraone (2012) Amazon.com;

“Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth”

by Walter Burkert (1972) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Greek Religion; Archaic and Classical Periods” by Walter Burkert (1985) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“On Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (Cornell Studies) (2011) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Religion” by Martin P. Nilsson (1925) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of the Gods” by Jacquetta Hawkes (1968) Amazom.com

“The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion” by Martin. Nilsson (1968) Amazon.com;

“Religions of the Hellenistic-Roman Age” by Antonia Tripolitis (2001) Amazon.com;

Why Sacrifices Were Held in Ancient Greece

It can be argued that in the ancient world sacrifices were at least partly based on the belief that sins could be laid on the victim, and in this way removed from the sinner. Sacrifices were as important to ancient Jews as they were to ancient Greels and Romans. Next to prayer, sacrifice was the commonest religious observance in ancient Greece. The anthropomorphic conception of the gods induced the Greeks to try to win their favor, as they would that of powerful princes, by means of gifts, in the belief that they would be more inclined to fulfill human wishes if they were propitiated by valuable presents. These gifts consisted in dedicatory offerings and also in sacrifices, and these had to be regularly offered in order to preserve the goodwill of the divinities. Generally speaking, any gift offered to the god might be regarded as a sacrifice; but, as a rule, this name was only applied to those offerings which were not to be a lasting possession of the god but were only given for momentary enjoyment, and must, as a rule, be destroyed, generally by means of fire. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The idea underlying these sacrifices was the participation of the gods in the material possessions of men. The gifts included under the heading of offerings were not all of such a nature as to be destroyed at once; thus, first-fruits of the field, fruit, jars of cooked lentils, flowers, fillets, and other such things could not be regarded as real gifts, owing to their transitory nature; and these were merely laid on the altar of the god, or else hung up beside it; sometimes there was a special table near the altar to receive these gifts.

As a rule, another purpose was combined with the sacrifice; it was necessary not only to win the favor of the gods, or atone for some crime, but also to discover the will of the gods by interpretation of signs. Although prayer was called for from all men — from labourer as well as from priest — and sacrifices, though usually offered by priests, could also be performed by others, the interpretation of omens was an art which depended on ancient traditions and knowledge of ritual, and was almost entirely confined to the priests, though, in the nature of things, it could be undertaken by anyone. This mode of prophecy had existed in various forms since the most ancient times. The commonest, though unknown in the time of Homer, was the examination of the entrails, in which the structure, that is, colour, form, and integrity of the inner parts of the victim, especially the liver, gall, etc., were regarded as of fortunate or unfortunate omen. Some anatomical knowledge of the inner parts of animals was therefore indispensable, and in consequence it is natural that this branch of knowledge was kept in the hands of the priests. The older kind of prophecy described in Homer was of a different nature, since it depended on all manner of phenomena appearing during the sacrifice; whether the flame attacked the victim quickly or slowly, whether it burnt clearly, whether it rose upwards, whether it was not put out until the whole animal was consumed, whether the wood crackled loudly, what shape was assumed by the ashes of the victim and of the wood, etc.

In a commentary in her blog a Don’s Life on modern neo-pagan revivals involving worship of the Greek gods, “As almost everyone who studies ancient Greek religion insists, the key centre of the whole religious system was sacrifice: it was the ritual of killing and sharing the animal that was, if anything, the “article of faith” that defined the ancient community of worshippers. And it was through sacrifice (rather than ecology) that ancient Greeks conceptualized their own place in the world — distinct from animals on the one hand and the superhuman gods on the other... Until these eager neo-pagans get real and slaughter a bull or two in central Athens, I shan’t worry that they have much to do with ancient religion at all. At the moment, this is paganism lite.”

Bloodless Sacrifice in Ancient Greece

Sacrifices wore usually divided into two classes — bloody and bloodless. The bloodless seem to be the most ancient; they consisted chiefly in the first-fruits of the field and cakes, usually made of honey, which were regarded as a specially welcome gift by some of the gods. Very often cakes were used as a substitute for animals, since poor people, who could not afford the considerable expense of sacrificing real animals, fashioned the dough into the shape of oxen, swine, sheep, goats, geese, etc. In this class we may include smoke offerings. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The custom of burning sweet-scented woods and spices probably came to Greece from Asia, where it had long prevailed. At first they made use of the products of the country, especially cedar wood; afterwards frankincense, storax, and other fragrant substances were introduced from foreign countries. These smoke offerings were often connected with animal sacrifices, since grains of incense were cast into the flames of the altar on which the flesh of the animal was burnt, in order to overpower the smell of burning meat.

Libations, too, may be included among bloodless sacrifices. Just as the gods required a portion of the food of men, they desired also to share in their drink, for they were supposed to require food and drink as men did. Libations were therefore offered before partaking of wine after a meal, or drinking any other draught, and Socrates even wished to offer some of his hemlock to the gods.

On other occasions too libations were offered, as for instance before public speeches, on the occasion of sacrifices for the dead, invocation of the gods for especial purposes, etc. The part of the wine or other liquid destined for the god was poured from a flat cup either on to the ground or into the flame of the altar, and words of consecration were spoken meantime. It was most usual to use unmixed wine, but there were some gods to whom no wine might be offered, in particular the Erinnys, the infernal deities, nymphs, Muses, etc.; to these they dedicated libations of honey, milk, or oil, either separately or mixed together, or with water. On these occasions there were certain fixed ceremonies to be observed, but these were not the same in all parts of Greece.

Animal Sacrifices in Ancient Greece

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The central ritual act in ancient Greece was animal sacrifice, especially of oxen, goats, and sheep. Animal sacrifices were performed with great care. One slip could spoil the whole thing. The choice of animals, methods of sacrifices used and the prayers and names invoked were all carefully selected. Before a sacrifice water was sprinkled on the brow of the animal. When the animals tried to shake it off it was viewed as a sign of assent. Whoever wished to consult an oracle had to offer a bull, a goat or a wild boar as a sacrifice. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Knives were used to sacrifice the animals, usually with a cut to the throat, and libation jars collected the blood from the animals necks. At the foot of a small mountain in Olympus small edifices were raised by each city-state to house jars which contained the blood of sacrificed animals. Usually sheep or cattle were sacrificed. Goats were sacrificed at rituals honoring Bacchus and cattle were sometimes garlanded and dresses as impersonators of gods.. Sacrificing a dog, cock or pig was seen as a sign of purification as was bathing in the sea. Apollo was depicted on vases as performing purification by dipping laurel leaves in the bowl most likely of pig's blood.

The animal chosen depended on the god to whom the sacrifice was offered. Here, as in the case of the bloodless sacrifices, some gods rejected gifts which were well-pleasing to others, and special animals were offered to particular gods. It is not always easy to trace the origin of this choice, though in some cases it can be done; thus, for instance, goats were offered to Dionysus because they destroyed the vineyards, and swine to Demeter because they injured the corn-fields. Oxen and sheep were the commonest victims next to goats and swine, and very often several animals were offered in a common sacrifice. Horses were offered to Poseidon and Helios, dogs to Hecate, asses to Apollo, etc. Birds, too, were sacrificed; for instance, geese, doves, fowls, and, in particular, cocks to Aesculapius. Game and fish were very seldom employed for the purpose, probably because they were not much used for food in ancient times; for in most cases the standard of eating decided which animals should be used, though there were exceptions, too, among the classes already named. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Animal Sacrifice Customs in Ancient Greece

As a rule, the animals sacrificed must be sound and healthy in every respect; but at Sparta, which was often reproached with excessive economy in sacrifices, diseased cattle were sometimes used. There were several other necessary conditions to be observed; thus, the animals must never have been in the service of man; the ox that drew the plough might not be sacrificed. The sex of the victim generally corresponded to that of the deity to whom it was offered. Even the colour was of importance; white animals were usually offered to the gods of light, black to the infernal gods. There do not seem to have been any fixed regulations with regard to age, except that the animals must have attained a certain maturity. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The ceremony observed at sacrifices was much the same throughout the whole of antiquity, and remained such as it is described by Homer. The victim which had been dedicated to the god, was adorned with wreaths and fillets, and led to the altar by servants or attendants; Homer speaks of gilding the horns of bulls, and this was customary afterwards. If possible, they tried to induce the animal to go forward of its own free will, since violent struggling was regarded as an unpropitious omen, and sometimes led to the rejection of the victim.

It was even customary to require the animal to give a sort of consent, by nodding its head; this consent of the victim was, of course, produced by artificial means, such as pouring water into the ears, etc. Hereupon all the participants in the solemn action were prepared by sprinkling with holy water, which was sanctified by dipping into it a firebrand taken from the altar, and they were exhorted to keep unbroken silence.

The flesh of the animals which was not used for the sacrifice was usually consumed at the feast which followed the ceremony; this custom was only departed from in the case of sacrifices to the shades of the dead or for purposes of propitiation, and then the flesh which was not burnt was buried or destroyed in some other way, and, in fact, on these occasions many of the ceremonies were of a different kind.

It was originally the custom to burn the whole animal, with skin and hair, but though this extravagant mode of sacrificing was sometimes in use in later times, it became common to burn only the thigh bones and certain flesh parts of the animal, and to use the rest for a festive banquet. In consequence the number of victims was often calculated according to the number of persons invited to the banquet; in other cases it depended on the importance of the occasion, or the fortune of the sacrificers, and even in historical times it was not unusual for whole communities or very rich private citizens to offer a hecatomb (a sacrifice of a hundred oxen), or even several, on which occasions the sacrifice only supplied the opportunity for entertaining the people on a magnificent scale.

How Animal Sacrifices Were Carried Out in Ancient Greece

The actual sacrifice then began by strewing roasted barleycorns, as the oldest food of their ancestors, on the animal, and in token of dedication they cut a bundle of hairs from its forehead and threw it into the fire, which was already burning on the altar. In heroic ages, the princes, as high priests, themselves killed the animals; afterwards this duty was undertaken by priests or attendants. They gave the animal a blow on its forehead with a club or axe, and then cut its throat with a sacrificial knife, and sprinkled the altar with the blood; in so doing they usually bent the head backwards; or, if sacrificing to the infernal gods, or the shades of the departed, they pressed it down to the ground.

When the victim fell, the women who stood round uttered a low cry, and in the ages after Homer it was very usual to accompany the whole ceremony by the sound of the flute. Experienced attendants then flayed the animals and cut up the bodies, whereupon the parts destined for the gods, especially the thigh bones surrounded with fat, were burnt in the flames of the altar with incense and sacrificial cakes, and at the same time libations were poured out; the flesh was held in the fire by means of long forks.

This is very often represented on ancient works of art. In a vase painting in we see an altar on which wood appears to be regularly piled up; parts of the sacrifice are recognised in the flames. An attendant wearing a short garment round his loins kneels in front, holding a piece of flesh in the flames on a long pole or spit; on his left a man holds a cup for libations, into which a goddess of victory, flying over the altar, pours the liquid; on the right stands Apollo, with lyre and plectrum.

Pig Sacrifice in Athens

Pigs were a favorite sacrificial animal as it was believed that purification by the blood of swine was supposed to have a special lustral power. At Athens it was the custom to sacrifice sucking-pigs before the assembly of the people was held; the slaughtered animals were carried round the assembly, the seats sprinkled with their blood, and the bodies thrown into the sea.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

On a vase painting representing the purification of Orestes after the murder of his mother, Apollo himself holds a sucking-pig above the head of the murderer; a similar proceeding is represented by the vase painting, where the woman who is performing the lustral rites — probably a priestess — holds in her right hand a sucking-pig, in her left a basket with offerings, while three torches stand on the ground in front of her, the smoke of which also possessed purifying power. Similar ceremonies were observed by those who, according to a very common superstition, regarded themselves as bewitched, or who desired to protect themselves from the injurious influence of philtres or other witchcraft, or else to cure madness, which was traced to the wrath of the infernal gods; in these cases, Hecate was the goddess to be propitiated, and part of the curious ceremony consisted in carrying about young dogs.

Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece

The Greeks and Romans considered human sacrifice immoral and uncivilized. Homer, however, describes captured Trojan being thrown onto the funeral pyre with the slain Greek soldiers under Achilles command. There are numerous indications in legends which show that the Greeks were not originally unacquainted with the custom of human sacrifices; but these are no longer heard of in the historic period, and wherever they had formerly existed their place was taken by symbolic actions, or the sacrifice of animals instead of human beings. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

At the beginning of the Trojan War, Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia for favorable sailing conditions to Troy. There are also real-life stories that support the idea that only the weakest in society should be sacrificed to the gods. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast In times of trouble, ancient Greeks practiced what was known as a pharmakos ritual. A beggar or prisoner-of-war would be dressed as a king and paraded around the city before being driven out, beaten, and — in many cases — killed. The purpose of the ritual was to purify the city, but rather than using an actual king a surrogate was supplied. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, April 10, 2016]

In literature, when people write about real or imagined sacrifice their victims are frequently children. Iphigenia is an example of how young girls were oddly likely to die at the hands of powerful fathers. In Euripides’ account of the Iphigeneia story, Iphigeneia comes around and resolves to die for her people claiming the future victory at Troy as her legacy. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 14, 2018]

According to the logic of ancient Greco-Roman sacrifice, a person seeking to placate, cajole, bribe, thank, or otherwise engage with a deity through the medium of sacrifice should use “perfect” or “the best” offerings. What the focus on vulnerability and female virginity in these stories obscures is that these people were, for all practical purposes, socially and politically powerless. Children were economic assets in the ancient world, but infants could easily die before adulthood. And girls were not as valuable as boys. It is rare (though not completely unheard of) for a military leader to immolate himself for the benefit of the group, and when he did it was for glory, fame, and military conquest. When the truly powerful were sacrificed it was only by proxy: in order to ward off disease the Greeks would sometimes dress a prisoner of war or a pauper as the king and parade him around before throwing him out of the city and (according to some scholars) killing him. But the king himself never actually died; it was just a show.

Ancient Jews were not the only ones who believed in the necessity of scapegoats. Similar rituals can be found among the ancient Greeks, Romans, Hittites, and in the mountains of the Tibet. As professor Jan Bremmer has written, the ancient Greeks were not averse to using humans as their scapegoats. In these rituals the scapegoat (or pharmakos, as he was known) would often enjoy a period of feasting and adulation before being driven out of the city (often while being beaten with sticks). In one example from the island of Leukas a criminal was thrown off a cliff into the sea in order to avoid evil. These scapegoat rituals seem to have regularly been associated with Thargelia, a festival held in late May in honor of the god Apollo, but they also took place in times of hardship, for example if the city was struck by disease or famine. Most of the candidates for the scapegoat were outsiders or liminal figures: criminals, prisoners of war, slaves, or very ugly people (one account says that “the ugliest person was selected”), but occasionally young people or even kings would be selected. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 08, 2019]

Three-thousand-year-old bones of a teenager found in 2016 on Mount Lykaion — a mountain where animal offerings to Zeus were made, in Arcadia in the Peloponnese area of Greece — appear to indicate that human sacrifice was practiced there in the time of the Mycenaeans but some scholars say some caution is in line on how the discovery should be interpreted. The upper part of the teenager’s skull was missing, while the body was laid among two lines of stones on an east-west axis, with stone slabs covering the pelvis. [Source: Mazin Sidahmed and agencies, The Guardian, August 10, 2016 ^^^]

See Separate Article: MYCENAEAN RELIGION: BEEHIVE TOMBS AND MAYBE HUMAN SACRIFICES europe.factsanddetails.com

Classical Sources on Ancient Greek Sacrifices

Clement of Alexandria wrote in “Stromata” (c. A.D. 200): “Sacrifices were devised by men, I do think, as a pretext for eating meals of meat.” On the sacrifice of a bull at funeral ceremony, Plutarch wrote in “Life of Aristides” (c. A.D. 110): “And the Plataeans undertook to make funeral offerings annually for the Hellenes who had fallen in battle and lay buried there. And this they do yet unto this day, after the following manner. On the sixteenth of the month Maimacterion (which is the Boiotian Alakomenius), they celebrate a procession. This is led forth at break of day by a trumpeter sounding the signal for battle; wagons follow filled with myrtle-wreaths, then comes a black bull, then free-born youths carrying libations of wine and milk in jars, and pitchers of oil and myrrh (no slave may put hand to any part of that ministration, because the men thus honored died for freedom); and following all, the chief magistrate of Plataea, who may not at other times touch iron or put on any other raiment than white, at this time is robed in a purple tunic, carries on high a water-jar from the city's archive chamber, and proceeds, sword in hand, through the midst of the city to the graves; there he takes water from the sacred spring, washes off with his own hands the gravestones, and anoints them with myrrh; then he slaughters the bull at the funeral pyre, and, with prayers to Zeus and Hermes Terrestrial, summons the brave men who died for Hellas to come to the banquet and its copious drafts of blood; next he mixes a mixer of wine, drinks, and then pours a libation from it, saying these words: "I drink to the men who died for the freedom of the Hellenes."” [Source: Plutarch, “Plutarch’s Lives,” translated by John Dryden, (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910)

human sacrifice at Polyxena? Lysias, an Athenian speech writer, wrote in “Against Nichomachos” (c. 400 B.C.): “I am informed that he alleges that I am guilty of impiety in seeking to abolish the sacrifices. But if it were I who were law-making over this transcription of our code, I should take it to be open to Nichomachos to make such a statement about me. But in fact I am merely claiming that he should obey the code established and patent to all and I am surprised at his not observing that, when he taxes me with impiety for saying that we ought to perform the sacrifices named in the tablets and pillars as directed in the regulations, he is accusing the city as well: for they are what you have decreed. And then, sir, if you feel these to be hard words, surely you must attribute grievous guilt to those citizens who used to sacrifice solely in accordance with the tablets. But of course, gentlemen of the jury, we are not to be instructed in piety by Nichomachos, but are rather to be guided by the ways of the past.

“Now our ancestors, by sacrificing in accordance with the tablets, have handed down to us a city superior in greatness and prosperity to any other in Hellas; so that it behooves us to perform the same sacrifices as they did, if for no other reason than that of the success which has resulted from those rites. And how could a man show greater piety than mine, when I demand, first that our sacrifices be performed according to our ancestral rules, and second that they be those which tend to promote the interests of the city, and finally those which the people have decreed and which we shall be able to afford out of the public revenue? But you, Nichomachos, have done the opposite of this: by entering in your copy a greater number than had been ordained you have caused the public revenue to be expended on these, and hence to be deficient for our ancestral offerings.”

Homer on Ancient Greek Sacrifices

Home wrote in “The Iliad” (ca. 800 B.C.): “And they did sacrifice each man to one of the everlasting gods, praying for escape from death and the tumult of battle. But Agamemnon, king of men, slew a fat bull of five years to most mighty Kronion, and called the elders, the princes of the Achaian host...Then they stood around the bull and took the barley meal, and Agamemnon made his prayer in their midst and said: "Zeus most glorious, most great god of the storm cloud, that lives in the heavens, make not the sun set upon us, nor the darkness come near, until I have laid low upon the earth Priam's palace smirched with smoke and burned the doorways thereof with consuming fire, and rent on Hector's breast his doublet, cleft with the blade; and about him may full many of his comrades, prone in the dust, bite the earth." [Source: Homer, “Homer's Iliad,” London: J. Cornish & Sons, 1862]

Alexander the Great makes a sacrifice to honor Achilles at Troy

“Now, when they had prayed and scattered the barley meal, they first drew back the bull's head and cut his throat and flayed him, and cut slices from the thighs and wrapped them in fat, making a double fold, and laid raw collops thereon. And these they burnt on cleft wood stripped of leaves, and spitted the vitals and held them over Hephaistos' flame. Now when the thighs were burnt and they had tasted the vitals, then sliced they all the rest and pierced it through with spits and roasted it carefully and drew all off again. So when they had rest from the task and had made ready the banquet, they feasted, nor was their heart stinted of the fair banquet.”

On a sacrifice for the dead, Homer wrote in The Odyssey, XI:18-50: Odysseus speaks: 'Thither we came and beached our ship, and took out the sheep, and ourselves went beside the stream of Oceanus until we came to the place of which Circe had told us. 'Here Perimedes and Eurylochus held the victims, while I drew my sharp sword from beside my thigh, and dug a pit of a cubit's length this way and that, and around it poured a libation to all the dead, first with milk and honey, thereafter with sweet wine, and in the third place with water, and I sprinkled thereon white barley meal. And I earnestly entreated the powerless heads of the dead, vowing that when I came to Ithaca I would sacrifice in my halls a barren heifer, the best I had, and pile the altar with goodly gifts, and to Teiresias alone would sacrifice separately a ram, wholly black, the goodliest of my flocks. But when with vows and prayers I had made supplication to the tribes of the dead, I took the sheep and cut their throats over the pit, and the dark blood ran forth. Then there gathered from out of Erebus the spirits of those that are dead, brides, and unwedded youths, and toil-worn old men, and tender maidens with hearts yet new to sorrow, and many, too, that had been wounded with bronze-tipped spears, men slain in fight, wearing their blood-stained armour. These came thronging in crowds about the pit from every side, with a wondrous cry, and pale fear seized me. Then I called to my comrades and bade them flay and burn the sheep that lay there slain with the pitiless bronze, and to make prayers to the gods, to mighty Hades and dread Persephone. And I myself drew my sharp sword from beside my thigh and sat there, and would not suffer the powerless heads of the dead to draw near to the blood until I had enquired of Teiresias. [Source: translation by A. T. Murray, in the Loeb Classical Library, vol. I (New York, 1919), PP. 387-9]

Sacrifice to Rhea: the Phrygian Mother-Goddess

On “A Sacrifice to Rhea, The Phrygian Mother-Goddess, Apollonius Rhodius wrote in “Argonautica,” I, 1078-1150: “After this, fierce tempests arose for twelve days and nights together and kept them there from sailing. But in the next night the rest of the chieftains, overcome by sleep, were resting during the latest period of the night, while Acastus and Mopsus the son of Ampycus kept guard over their deep slumbers. And above the golden head of Aeson's son there hovered a halcyon prophesying with shrill voice the ceasing of the stormy winds; and Mopsus heard and understood the cry of the bird of the shore, fraught with good omen. And some god made it turn aside, and flying aloft it settled upon the stern-ornament of the ship. [Source: translation by R. C. Seaton, in the Loeb Classical Library (New York, 1912), PP. 77-81]

Rhea

“And the seer touched Jason as he lay wrapped in soft sheepskins and woke him at once, and thus spake: ‘'Son of Aeson, thou must climb to this temple on rugged Dindymum and propitiate the mother (i.e., Rhea) of all the blessed gods on her fair throne, and the stormy blasts shall cease. For such was the voice I heard but now from the halcyon, bird of the sea, which, as it flew above thee in thy slumber, told me all. For by her power the winds and the sea and all the earth below and the snowy seat of Olympus are complete; and to her, when from the mountains she ascends the mighty heaven, Zeus himself, the son of Cronos, gives place. In like manner the rest of the immortal blessed ones reverence the dread goddess.'

“Thus he spake, and his words were welcome to Jason's ear. And he arose from his bed with joy and woke all his comrades hurriedly and told them the prophecy of Mopsus the son of Ampycus. And quickly the younger men drove oxen from their stalls and began to lead them to the mountain's lofty summit. And they loosed the hawsers from the sacred rock and rowed to the Thracian harbour; and the heroes climbed the mountain, leaving a few of their comrades in the ship. And to them, the Macrian heights and all the coast of Thrace opposite appeared to view dose at hand. And there appeared the misty mouth of Bosporus and the Mysian hills; and on the other side the stream of the river Aesepus and the city and Nepian plain of Adrasteia. Now there was a sturdy stump of vine that grew in the forest, a tree exceeding old; this they cut down, to be the sacred image of the mountain goddess; and Argos smoothed it skillfully, and they set it upon that rugged hill beneath a canopy of lofty oaks, which of all trees have their roots deepest. And near it they heaped an altar of small stones and wreathed their brows with oak leaves and paid heed invoking the mother of Dindymum, most venerable, dweller in Phrygia and Titas and Cyllenus, who alone of many are called dispensers of doom and assessors of the Idaean mother-the Idaean Dactyls of Crete, whom once the nymph Anchiale, as she grasped with both hands the land of Oaxus, bare in the Dictaean cave. And with many prayers did Aeson's son beseech the goddess to turn aside the stormy blasts as he poured libations on the blazing sacrifice; and at the same time by command of Orpheus the youths trod a measure dancing in full armour, and dashed with their swords on their shields, so that the ill-omened cry might be lost in the air-the wail which the people were still sending up in grief for their king. Hence from that time forward the Phrygians propitiate Rhea with the wheel and the drum. And the gracious goddess, I ween, inclined her heart to pious sacrifices; and favourable signs appeared. The trees shed abundant fruit, and round their feet the earth of its own accord put forth flowers from the tender grass. And the beasts of the wild wood left their lairs and thickets and came up fawning on them with their tails. And she caused yet another marvel; for hitherto there was no flow of water on Dindymum, but then for them an unceasing stream gushed forth from the thirsty peak just as it was, and the dwellers around in after times called that stream, the spring of Jason. And then they made a feast in honour of the goddess on the Mount of Bears, singing the praises of Rhea most venerable; but at dawn the winds had ceased and they rowed away from the island.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024