Home | Category: Religion and Gods

CYBELE

Magna Mater ("Great Mother") was the Roman version of Cybele, an Anatolian mother goddess that may date back to 10,0000-year-old Çatalhöyük, the world’s oldest town, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations. She is Phrygia's only known goddess, and was probably its state deity. Her Phrygian cult was adopted and adapted by Greek colonists of Asia Minor and spread to mainland Greece and its more distant western colonies around the 6th century B.C..

In Greece, Cybele was greeted with a mixed reception. She became partially assimilated to aspects of the Earth-goddess Gaia, of her possibly Minoan equivalent Rhea, and of the harvest–mother goddess Demeter. Some city-states, notably Athens, evoked her as a protector, but her most celebrated Greek rites and processions depict her as a exotic, foreign mystery-goddess carried in a lion-drawn chariot, accompanied by wild music, wine, and a chaotic ecstatic following. Apparently primarily in Greek religion, her cult was led by eunuch mendicant priests. Many of her Greek cults included rites to a divine Phrygian castrate shepherd-consort Attis, who was probably a Greek invention. In Greece, Cybele became associated with mountains, town and city walls, fertile nature, and wild animals, especially lions.

Some of the rites of the Cybele cults like the bull sacrifice of the Great Mother and the procession of the torn-up pine which accompanied the mutilation of Attis were viewed as both barbarous and indecent "like a whiff from slaughter-house or latriae." But scholars some have said that they provided a tonic and beneficent influence on individuals and lifted them to a higher plane.

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele” by Lynn E. Roller (1999) Amazon.com;

“Mother of the Gods: From Cybele to the Virgin Mary” by Philippe Borgeaud (2004) Amazon.com;

“Rome And The Magna Mater Or The Worship Of The Great Mother” by Samuel Dill (1844-1924) Amazon.com;

“Vestal Virgins, Sibyls, and Matrons: Women in Roman Religion”

by Sarolta A. Takács (2022) Amazon.com;

"Cybele and Attis: the Myth and the Cult” by Maarten J. Vermaseren (1977) Amazon.com;

“Cybele, Attis and Related Cults: Essays in Memory of M.J. Vermaseren” by Eugene N. Lane (1996) Amazon.com;

“Aspects of the Cult of Cybele and Attis on the Monuments from the Republic of Croatia” by Aleksandra Nikoloska (2010) Amazon.com;

“Demeter, Isis, Vesta, and Cybele: Studies in Greek and Roman Religion in Honour of Giulia Sfameni Gasparro” by Attilio Mastrocinque, Concetta Giuffre Scibona (2012) Amazon.com;

“Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Mystery-Religions” by S. Angus (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Secret Sacred: Mystery Cults in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Damien Stone (2025) Amazon.com;

“God Who Comes, Dionysian Mysteries Reclaimed: Ancient Rituals, Cultural Conflicts, and Their Impact on Modern Religious Practices” (2003) by Rosemarie Taylor-Perry Amazon.com;

“The Greco-Roman Cult of Isis” by Harold R. Willoughby (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner” by Harriet I. Flower (2017) Amazon.com;

“Magic and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World” by Radcliffe G. Edmonds III and Carolina López-Ruiz (2023) Amazon.com

Magna Mater Cult

The Roman state adopted and developed a particular form of Magna Mater ("Great Mother", Cybele) cult after the Sibylline oracle in 205 B.C. recommended her conscription as a key religious ally in the Second Punic War — Rome's second war against Carthage (218 to 201 BC). Roman myths appeared that reinvented her as a Trojan goddess, and thus an ancestral goddess of the Roman people by way of the Trojan prince Aeneas. As Rome eventually established hegemony over the Mediterranean world, Romanized forms of Cybele's cults spread throughout Rome's empire. Greek and Roman writers debated and disputed the meaning and morality of her cults and priesthoods, which remain controversial subjects in modern scholarship. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 204 B.C., during the Second Punic War, the Romans consulted the Sibylline Oracles, which declared that the foreign invader would be driven from Italy only if the Idaean Mother (Cybele) from Anatolia were brought to Rome. The Roman political elite, in a carefully orchestrated effort to unify the citizenry, arranged for Cybele to come inside the pomerium (a religious boundary-wall surrounding a city), built her a temple on the Palatine Hill, and initiated games in honor of the Great Mother, an official political and social recognition that restored the pax deorum. [Source: Claudia Moser, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“After Cybele and the foreign ways of her exotic priesthood were introduced to Rome, she became a popular goddess in Roman towns and villages in Italy. But the enthusiasm that accompanied the establishment of her cult was soon followed by suspicion and legal prohibitions. The eunuch priests (galli) that attended Cybele's cult were confined in the sanctuary; Roman men were forbidden to castrate themselves in imitation of the galli, and only once a year were these eunuchs, dressed in exotic, colorful garb, allowed to dance through the streets of Rome in jubilant celebration. Nevertheless, the popularity of the goddess persisted, especially in the Imperial period, when the ruling family, eager to emphasize its Trojan ancestry, associated itself with and publicly worshipped Cybele, a goddess whose epithet, Mater Idaea, designated her as Trojan and whose cult was deeply connected with Troy and its origins.” \^/

Attis

Attis began as a Phrygian vegetation deity. In classical antiquity, Phrygia was a kingdom in the west-central part of Anatolia (Turkey), centered on the Sangarios River. In Phrygian and Greek mythology Attis was the consort of Cybele. His priests were eunuchs, the Galli, who follow Attis’s act of castrating himself. Attis’ self-mutilation, death, and resurrection represents the fruits of the earth, which die in winter only to rise again in the spring. [Source Wikipedia]

An Attis cult began around 1250 B.C. in Dindymon (today's Murat Dağı of Gediz, Kütahya, Turkey). He was originally a local semi-deity of Phrygia, associated with the great Phrygian trading city of Pessinos, near Mount Agdistis. The mountain was personified as a daemon, whom foreigners associated with the Great Mother Cybele. In the late 4th century B.C., a cult of Attis became a feature of the Greek world. The story of his origins at Agdistis recorded by the traveller Pausanias was distinctly non-Greek and had some elements that were even weird by ancient Greek standards.

According to Ovid's Metamorphoses, Attis transformed himself into a pine tree. "Hymn to the Mother of Gods" by Emperor Julian (A.D. 331–363) contains a detailed Neoplatonic analysis of Attis. In that work Julian says: "Of him [Attis] the myth relates that, after being exposed at birth near the eddying stream of the river Gallus, he grew up like a flower, and when he had grown to be fair and tall, he was beloved by the Mother of the Gods. And she entrusted all things to him, and moreover set on his head the starry cap."On this passage, the scholiast (Wright) says: "The whole passage implies the identification of Attis with nature."

The first literary reference to Attis is the subject of one of the most famous poems by Catullus (Catullus 63), apparently before Attis had begun to be worshipped in Rome, as Attis' worship began in the early Empire. In 1675, Jean-Baptiste Lully, who was attached to Louis XIV's court, composed an opera titled Atys. In 1780, Niccolo Piccinni composed his own Atys. Oscar Wilde mentions Attis' self-mutilation in his poem The Sphinx, published in 1894:

"And Atys with his blood-stained knife

were better than the thing I am."

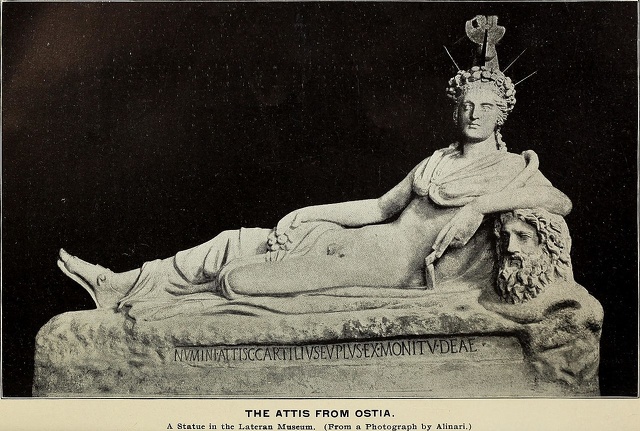

The most important representation of Attis is the lifesize statue discovered at Ostia Antica, near the mouth of Rome's river. The statue is of a reclining Attis, after the emasculation. In his left hand is a shepherd's crook, in his right hand a pomegranate. His head is crowned with a pine garland with fruits, bronze rays of the sun, and on his Phrygian cap is a crescent moon. It was discovered in 1867 at the Campus of the Magna Mater together with other statues.

Attis Myth

Pausanias said that the daemon Agdistis initially had both male and female sexual organs. The Olympian gods feared Agdistis and they conspired to cause Agditis to accidentally castrate itself, ridding itself of its male organs. From the hemorrhage of Agdistis germinated an almond tree. When the fruits ripened, Nana, daughter of the river Sangarius, took an almond, put it in her bosom, and later became pregnant with baby Attis, whom she abandoned. [Source Wikipedia]

The infant was tended by a he-goat. As Attis grew, his long-haired beauty was godlike, and his parent, Agdistis (as Cybele) then fell in love with him. But Attis' foster parents sent him to Pessinos, where he was to wed the king's daughter.

According to some versions of the story the king of Pessinos was Midas. Just as the marriage-song was being sung, Agdistis (Cybele) appeared in her transcendent power, and Attis went mad and castrated himself under a pine. When he died as a result of his self-inflicted wounds, violets grew from his blood. Attis' father-in-law-to-be, the king who was giving his daughter in marriage, followed suit, prefiguring the self-castrating corybantes who devoted themselves to Cybele. The heartbroken Agdistis begged Zeus, the Father God, to preserve Attis so his body would never decay or decompose.

At the temple of Cybele in Pessinus, the mother of the gods was still called Agdistis, the geographer Strabo wrote As neighbouring Lydia came to control Phrygia, the cult of Attis was given a Lydian context too. Attis is said to have introduced to Lydia the cult of the Mother Goddess Cybele, incurring the jealousy of Zeus, who sent a boar to destroy the Lydian crops. Then certain Lydians, with Attis himself, were killed by the boar. Pausanias adds, to corroborate this story, that the Gauls who inhabited Pessinos abstained from pork. This myth element may have been invented solely to explain the unusual dietary laws of the Lydian Gauls. In Rome, the eunuch followers of Cybele were called galli.

History of the Cybele Cult in Ancient Rome

Cybele priest Gallus,_Archigalles

The Magna Mater originated in the state of Phrygia in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey) as was brought to Rome in 205 B.C., during the Second Punic War, but, when the orgiastic nature of the cult became known, it was ordained that her priests should never be Romans. Some describe this as the beginning of the “Oriental” religions movement in ancient Rome, with “Oriental” primarily meaning the Middle East, Egypt and Asia Minor. During a period of religious revivalism in the late Imperial era, notbale Magna Mater's initiates included the deeply religious, wealthy, and erudite praetorian prefect Praetextatus; the quindecimvir Volusianus, who was twice consul; and possibly the Emperor Julian.

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Cybele, the first Oriental divinity to be found acceptable in Rome since the end of the third century B.C., was long an oddity in the city. As the Mater Magna (Great Mother), she had been imported by governmental decision, she had a temple within the pomerium, and she was under the protection of members of the highest Roman aristocracy. Yet her professional priests, singing in Greek and living by their temple, were considered alien fanatics even in imperial times. What is worse, the goddess also had servants, the Galli, who had castrated themselves to express their devotion to her. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Under the emperor Claudius, Roman citizens were probably allowed some priestly functions, though the matter is very obscure. Even more obscure is how Attis became Cybele's major partner. He is so poorly attested in the republican written evidence for the cult of Cybele that scholars used to believe that he was introduced to the cult only in the first century ce (they saw Catullus 63 as a purely "literary" text).

However, excavations at the Palatine temple of Mater Magna discovered a major cache of statuettes of Attis dating to the second and first centuries B.C. The find hints that religious life in republican Rome was more varied than the written record suggests. A new festival, from March 15 to 27, apparently put special emphasis on the rebirth of Attis. Concurrently, the cult of Cybele became associated with the ritual of the slaying of the sacred bull (taurobolium), which the Christian poet Prudentius (Peristephanon 10.1006–1050) interpreted as a baptism of blood (though his depiction of the ritual is deeply suspect, forming part of a fierce and late antipagan polemic). The taurobolium was performed for the prosperity of the emperor or of the Empire and, more frequently, for the benefit of private individuals. Normally it was considered valid for twenty years, which makes it highly questionable whether it was meant to confer immortality on the baptized.

Livy on Magna Mater Cults

Livy wrote in “History of Rome” (A.D. c. 10): “About this time the citizens were much exercised by a religious question which had lately come up. Owing to the unusual number of showers of stones which had fallen during the year, an inspection had been made of the Sibylline Books, and some oracular verses had been discovered which announced that whenever a foreign foe should carry war into Italy he could be driven out and conquered if the Mater Magna were brought from Pessinos [in Phrygia] to Rome. [Source: Livy, “The History of Rome,” by Titus Livius, translated by D. Spillan and Cyrus Edmonds, (New York: G. Bell & Sons, 1892); The Bible (Douai-Rheims Version), (Baltimore: John Murphy Co., 1914)]

Magna Mater box

The discovery of this prediction produced all the greater impression on the senators because the deputation who had taken the gift to Delphi reported on their return that when they sacrificed to the Pythian Apollo the indications presented by the victims were entirely favorable, and further, that the response of the oracle was to the effect that a far grander victory was awaiting Rome than the one from whose spoils they had brought the gift to Delphi. In order, therefore, to secure all the sooner the victory which the Fates, the omens, and the oracles alike foreshadowed, they began to think out the best way of transporting the goddess to Rome.

“In this state of excitement men's minds were filled with superstition and the ready credence given to announcement of portents increased their number. Two suns were said to have been seen; there were intervals of daylight during the night; a meteor was seen to shoot from east to west; a gate at Tarracina and at Anagnia a gate and several portions of the wall were struck by lightning; in the temple of Juno Sospita at Lanuvium a crash followed by a dreadful roar was heard. To expiate these portents special intercessions were offered for a whole day, and in consequence of a shower of stones a nine days' solemnity of prayer and sacrifice was observed. The reception of Mater Magna was also anxiously discussed. M. Valerius, the member of the deputation who had come in advance, had reported that she would be in Italy almost immediately and a fresh messenger had brought word that she was already at Tarracina. Scipio was ordered to go to Ostia, accompanied by all the matrons, to meet the goddess. He was to receive her as she left the vessel, and when brought to land he was to place her in the hands of the matrons who were to bear her to her destination.

“As soon as the ship appeared off the mouth of the Tiber he put out to sea in accordance with his instructions, received the goddess from the hands of her priestesses, and brought her to land. Here she was received by the foremost matrons of the City, amongst whom the name of Claudia Quinta stands out pre-eminently. According to the traditional account her reputation had previously been doubtful, but this sacred function surrounded her with a halo of chastity in the eyes of posterity. The matrons, each taking their turn in bearing the sacred image, carried the goddess into the temple of Victory on the Palatine. All the citizens flocked out to meet them, censers in which incense was burning were placed before the doors in the streets through which she was borne, and from all lips arose the prayer that she would of her own free will and favor be pleased to enter Rome. The day on which this event took place was 12th April, and was observed as a festival; the people came in crowds to make their offerings to the deity; a lectisternium [7-day citywide feast] was held, and Games were constituted which were known afterwards as the Megalesian.

Magna Mater Worship

The Magna Mater goddess reportedly was served by self-emasculated priests known as galli. Until the emperor Claudius, Roman citizens could not become priests of Cybele, but after that worship of her and her lover Attis took their place in the state cult. One aspect of the cult was the use of baptism in the blood of a bull, a practice later taken over by Mithraism. [Source: Lucretius, “On the Nature of Things,” translation by William Ellery Leonard. Complete version online at MIT classics.mit.edu/Carus/nature_things]

Magna Mater altars

Describing the cult, the Epicurean poet Lucretius (98-c.55 B.C.) wrote in “On the Nature of Things”:

“Wherefore great mother of gods, and mother of beasts,

And parent of man hath she alone been named.

Her hymned the old and learned bards of Greece.

Seated in chariot o'er the realms of air

To drive her team of lions, teaching thus

That the great earth hangs poised and cannot lie

Resting on other earth. Unto her car

They've yoked the wild beasts, since a progeny,

However savage, must be tamed and chid

By care of parents. They have girt about

With turret-crown the summit of her head,

Since, fortressed in her goodly strongholds high,

'Tis she sustains the cities; now, adorned

With that same token, to-day is carried forth,

With solemn awe through many a mighty land,

The image of that mother, the divine.

Her the wide nations, after antique rite,

Do name Idaean Mother, giving her

Escort of Phrygian bands, since first, they say,

From out those regions 'twas that grain began

Through all the world. To her do they assign

The Galli, the emasculate, since thus

They wish to show that men who violate

The majesty of the mother and have proved

Ingrate to parents are to be adjudged

Unfit to give unto the shores of light

A living progeny. The Galli come:

And hollow cymbals, tight-skinned tambourines

Resound around to bangings of their hands;

The fierce horns threaten with a raucous bray;

The tubed pipe excites their maddened minds

In Phrygian measures; they bear before them knives,

Wild emblems of their frenzy, which have power

The rabble's ingrate heads and impious hearts

To panic with terror of the goddess' might.

And so, when through the mighty cities borne,

She blesses man with salutations mute,

They strew the highway of her journeyings

With coin of brass and silver, gifting her

With alms and largesse, and shower her and shade

With flowers of roses falling like the snow

Upon the Mother and her companion-bands.

Here is an armed troop, the which by Greeks

Are called the Phrygian Curetes. Since

“Haply among themselves they use to play

In games of arms and leap in measure round

With bloody mirth and by their nodding shake

The terrorizing crests upon their heads,

This is the armed troop that represents

The arm'd Dictaean Curetes, who, in Crete,

As runs the story, whilom did out-drown

That infant cry of Zeus, what time their band,

Young boys, in a swift dance around the boy,

To measured step beat with the brass on brass,

That Saturn might not get him for his jaws,

And give its mother an eternal wound

Along her heart. And it is on this account

That armed they escort the mighty Mother,

Or else because they signify by this

That she, the goddess, teaches men to be

Eager with armed valour to defend

Their motherland, and ready to stand forth,

The guard and glory of their parents' years.”

Sacred Orgy of Cybele

Catullus (c.84-c.54 B.C.) wrote in Carmina 63: “Over the vast main borne by swift-sailing ship, Attis, as with hasty hurried foot he reached the Phrygian wood and gained the tree-girt gloomy sanctuary of the Goddess, there roused by rabid rage and mind astray, with sharp-edged flint downwards dashed his burden of virility. Then as he felt his limbs were left without their manhood, and the fresh-spilt blood staining the soil, with bloodless hand she hastily took a tambour light to hold, your taborine, Cybele, your initiate rite, and with feeble fingers beating the hollowed bullock's back, she rose up quivering thus to chant to her companions. [Source: Catullus, “The Carmina of Gaius Valerius Catullus,” translated by. Leonard C. Smithers. London. Smithers. 1894]

““Haste you together, she-priests, to Cybele's dense woods, together haste, you vagrant herd of the dame Dindymene, you who inclining towards strange places as exiles, following in my footsteps, led by me, comrades, you who have faced the ravening sea and truculent main, and have castrated your bodies in your utmost hate of Venus, make glad our mistress speedily with your minds' mad wanderings. Let dull delay depart from your thoughts, together haste you, follow to the Phrygian home of Cybele, to the Phrygian woods of the Goddess, where sounds the cymbal's voice, where the tambour resounds, where the Phrygian flutist pipes deep notes on the curved reed, where the ivy-clad Maenades furiously toss their heads, where they enact their sacred orgies with shrill-sounding ululations, where that wandering band of the Goddess flits about: there it is meet to hasten with hurried mystic dance.”

“When Attis, spurious woman, had thus chanted to her comity, the chorus straightway shrills with trembling tongues, the light tambour booms, the concave cymbals clang, and the troop swiftly hastes with rapid feet to verdurous Ida. Then raging wildly, breathless, wandering, with brain distraught, hurries Attis with her tambour, their leader through dense woods, like an untamed heifer shunning the burden of the yoke: and the swift Gallae press behind their speedy-footed leader. So when the home of Cybele they reach, wearied out with excess of toil and lack of food they fall in slumber. Sluggish sleep shrouds their eyes drooping with faintness, and raging fury leaves their minds to quiet ease.

“But when the sun with radiant eyes from face of gold glanced over the white heavens, the firm soil, and the savage sea, and drove away the glooms of night with his brisk and clamorous team, then sleep fast-flying quickly sped away from wakening Attis, and goddess Pasithea received Somnus in her panting bosom. Then when from quiet rest torn, her delirium over, Attis at once recalled to mind her deed, and with lucid thought saw what she had lost, and where she stood, with heaving heart she backwards traced her steps to the landing-place. There, gazing over the vast main with tear-filled eyes, with saddened voice in tristful soliloquy thus did she lament her land:

““Mother-land, my creatress, mother-land, my begetter, which full sadly I'm forsaking, as runaway serfs do from their lords, to the woods of Ida I have hasted on foot, to stay amid snow and icy dens of beasts, and to wander through their hidden lurking-places full of fury. Where, or in what part, mother-land, may I imagine that you are? My very eyeball craves to fix its glance towards you, while for a brief space my mind is freed from wild ravings. And must I wander over these woods far from my home? From country, goods, friends, and parents, must I be parted?

Magna Mater figure

Leave the forum, the palaestra, the race-course, and gymnasium? Wretched, wretched soul, it is yours to grieve for ever and ever. For what shape is there, whose kind I have not worn? I (now a woman), I a man, a stripling, and a lad; I was the gymnasium's flower, I was the pride of the oiled wrestlers: my gates, my friendly threshold, were crowded, my home was decked with floral garlands, when I used to leave my couch at sunrise. Now will I live a ministrant of gods and slave to Cybele? I a Maenad, I a part of me, I a sterile trunk! Must I range over the snow-clad spots of verdurous Ida, and wear out my life beneath lofty Phrygian peaks, where stay the sylvan-seeking stag and woodland-wandering boar? Now, now, I grieve the deed I've done; now, now, do I repent!”

“As the swift sound left those rosy lips, borne by new messenger to gods' twinned ears, Cybele, unloosing her lions from their joined yoke, and goading, the left-hand foe of the herd, thus speaks: “Come,” she says, “to work, you fierce one, cause a madness urge him on, let a fury prick him onwards till he returns through our woods, he who over-rashly seeks to fly from my empire. On! thrash your flanks with your tail, endure your strokes; make the whole place re-echo with roar of your bellowings; wildly toss your tawny mane about your nervous neck.” Thus ireful Cybele spoke and loosed the yoke with her hand. The monster, self-exciting, to rapid wrath spurs his heart, he rushes, he roars, he bursts through the brake with heedless tread. But when he gained the humid verge of the foam-flecked shore, and spied the womanish Attis near the opal sea, he made a bound: the witless wretch fled into the wild wood: there throughout the space of her whole life a bondsmaid did she stay. Great Goddess, Goddess Cybele, Goddess Dame of Dindymus, far from my home may all your anger be, 0 mistress: urge others to such actions, to madness others hound.”

Magna Mater Taurobolium (Bull Sacrifice)

The Taurobolium — bull sacrifice ritual — was the most potent and costly victim Magna Mater rituals. In the lesser Criobolium, a ram was usually sacrificed. These rituals were not tied to any particular date or festival. The participant personally and symbolically took the place of Attis, and like him was cleansed, renewed or, in emerging from the pit or tomb, "reborn". [Source Wikipedia]

A late and dramatic account by the Christian apologist Prudentius said a priest stood in a pit beneath a slatted wooden floor. His assistants or junior priests killed the bull, using a sacred spear. The priest emerged from the pit, drenched with the bull's blood, to the applause of the spectators. This description of a Taurobolium as blood-bath is, if accurate, differs from usual Roman sacrificial practice. It has been argued that more likely the Taurobolium was a normal bull sacrifice in which the blood was carefully collected and offered to the deity, along with its organs of fertility, the testicles.

The high cost of the Taurobolium meant that its initiates were from Rome's highest class, and even the lesser offering of a Criobolium would have been beyond the means of the poor. Among the Roman masses, there is evidence of private devotion to Attis, but virtually none for initiations to Magna Mater's cult. Taurobolium dedications to Magna Mater tend to be more common in the Empire's western provinces than elsewhere, attested by inscriptions in Rome, Ostia in Italy, Lugdunum in Gaul, Carthage in Africa and other places

Christian View of a “Bloody” Magna Mater Ritual

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens (A.D. 348-418), a Roman Christian poet, wrote at time when Christianity had become established and “paganism” was caste in an unfavorable light: “The high priestess who is to be consecrated is brought down under ground in a pit dug deep, marvellously adorned with a fillet, binding her festive temples with chaplets, her hair combed back under a golden crown, and wearing a silken toga caught up with Gabine girding. Over this they make a wooden floor with wide spaces, woven of planks with an open mesh; they then divide or bore the area and repeatedly pierce the wood with a pointed tool that it may appear full of small holes.

Magna Mater votive relief

“Here a huge bull, fierce and shaggy in appearance, is led, bound with flowery garlands about its flanks, and with its horns sheathed---its forehead sparkles with gold, and the flash of metal plates colors its hair. Here, as is ordained, they pierce its breast with a sacred spear; the gaping wound emits a wave of hot blood, and the smoking river flows into the woven structure beneath it and surges wide. Then by the many paths of the thousand openings in the lattice the falling shower rains down a foul dew, which the priestess buried within catches, putting her head under all the drops.

She throws back her face, she puts her cheeks in the way of the blood, she puts under it her ears and lips, she interposes her nostrils, she washes her very eyes with the fluid, nor does she even spare her throat but moistens her tongue, until she actually drinks the dark gore. Afterwards, the corpse, stiffening now that the blood has gone forth, is hauled off the lattice, and the priestess, horrible in appearance, comes forth, and shows her wet head, her hair heavy with blood, and her garments sodden with it. This woman, all hail and worship at a distance, because the ox's blood has washed her, and she is born again for eternity.”

Galli — the Self-Castrated Cybele Cult Priests

Galli were eunuch priests of the Magna Mater cult. The earliest surviving references to a gallus is from the Greek Anthology, a 10th-century compilation of earlier material, where several epigrams mention or clearly allude to their castrated state. Dionysius of Halicarnassus claimed that Roman citizens did not participate in the rituals of the cult of Magna Mater. Literary sources call the galli "half-men," leading scholars to conclude that Roman men looked down on them, galli but this could be the result of official Roman disapproval of the foreign cult by modern scholars than a social reality in Rome. Archaeologists have found votive statues of Attis on the Palatine hill, meaning people in Rome, not just the provinces, participated in Magna Mater cult. [Source Wikipedia]

The symbols of being a galli were a type of crown, possibly a laurel wreath, as well as a golden bracelet known as the occabus. Galli generally wore women's clothing (often yellow), and a turban, pendants, and earrings. They bleached their hair and wore it long, and they wore heavy makeup. They wandered around with followers, begging for charity, in return for which they were prepared to tell fortunes.

Magna Mater Taurobolium

In Rome, the head of the galli was known as the archigallus. A number of archaeological finds depict the archigallus wearing luxurious and extravagant costumes.The archigallus was a Roman citizen and an employee of the Roman State, and had to be careful not to violate any Roman religious prohibitions. Some argue that the archigallus was never a eunuch, as all citizens of Rome were forbidden from eviratio (castration). This prohibition also suggests that the original galli were either Asian or slaves. The Emperor Claudius (A.D. 41–54) lifted the ban on castration; but Domitian (A.D. 81–96) reaffirmed it.

Rome's strictures against castration and citizen participation in Magna Mater's cult limited both the number and kind of her initiates. From the A.D. 160s AD, citizens who sought initiation to her mysteries could offer either of two forms of bloody animal sacrifice – and sometimes both – as lawful substitutes for self-castration.

The remains of a Roman gallus from the A.D. 4th century was found in 2002 in what is now Catterick, England, dressed in women's clothes, with jewelry made of jet, shale, and bronze, and with two stones in his mouth. Pete Wilson, the senior archaeologist at English Heritage, was involved in the find.

Galli Self-Castration and the Day of Blood

The galli castrated themselves during an ecstatic celebration called Sanguem or Dies Sanguinis ("Day of Blood") which took place on March 24. On this day of mourning for Attis, they ran around wildly and disheveled. They performed dances to the music of pipes and tambourines, and, in an ecstasy, flogged themselves until they bled This was followed by a day of feasting and rest. [Source Wikipedia]

During Sanguem was held around the spring equinox. Before the day of Blood there were two days of mourning for the annual death of Attis. On the Day of Blood devotees that whipped themselves sprinkled the altars and effigy of Attis with their blood. Some performed the self-castrations of the Galli. The "sacred night" followed, with Attis placed in his ritual tomb. The Day of Blood was followed by a Day of Joy and Relaxation (Hilaria and Requietio) to celebrate Attis' resurrection. This was followed by a rest day, and then a day of revelry during which an image of Cybele was bathed in the Little Almo River (Lavatio).

A sacred feast was part of the initiation ritual. Firmicus Maternus, a Christian who objected to other religions, revealed a possible password of the galli: "I have eaten from the timbrel; I have drunk from the cymbal; I am become an initiate of Attis." That password is cited in the book De errore profanarum religionum. The Eleusinian Mysteries, reported by Clement of Alexandria, include a similar formula: "I fasted; I drank the kykeon [water with meal]; I took from the sacred chest; I wrought therewith and put it in the basket, and from the basket into the chest."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024