Home | Category: Neanderthal Art and Culture / First Modern Human Art and Culture

WORLD’S OLDEST MUSIC

Musical instruments were one of the first forms of artistic expression to appear. Some scholars, including Darwin, speculated they appeared before speech. Drums and other percussion instruments were presumably among the first instruments to appear. Red painted mammoth bones found at Paleolithic sites may have been used as percussion instruments. Instruments resembling bull-roarers made of bone and ivory have been found at very old sites.

The bow may have been one of the world’s first music instruments. Seven-thousand-year old cave painting in the Sahara depict bows being used as instruments. Bushmen today make haunting music with such a bow-like an instrument. The bow that is placed in the mouth. Sound is produced by tapping a sinew string with a reed. Modern instruments such as the Chinese “ehru” are essentially bows.

Nicholas J. Conard of the University of Tübingen, in Germany wrote in Nature that music in the Stone Age “could have contributed to the maintenance of larger social networks, and thereby perhaps have helped facilitate the demographic and territorial expansion of modern humans." To visualize ancient music in a modern and totally musical context you can try the modern music visualizer.

Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution; The Neanderthal Flute, by Bob Fink greenwych.ca

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body”

by Steven Mithen (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Smart Neanderthal: Bird catching, Cave Art, and the Cognitive Revolution”

by Clive Finlayson Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science Is Rewriting Their Story”

by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse (2022) Amazon.com;

Neanderthal Religion? : Theology in Dialogue with Archaeology” by Thomas Hughson Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

Neanderthal Flute — the World’s Oldest Musical Instrument

The Divje Babe flute, also called tidldibab, is regarded as the world’s oldest musical instrument. Made from a cave bear femur pierced by spaced holes, it was unearthed in 1995 in Divje Babe cave near Cerkno in northwestern Slovenia, by the Institute of Archaeology of the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. It has been dated to be 50,000 to 60,000 years old, before modern humans arrived in the region, and is this is presumed to have been made by Neanderthals. The 11.4-centimeter (4.5 inch) artifact is on prominent public display in the National Museum of Slovenia in Ljubljana as a Neanderthal flute. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the National Museum of Slovenia The 60,000-year-old Neanderthal flute is made from the left thighbone of a young cave bear and has four pierced holes (two well-preserved ones and two damaged ones). Musical experiments confirmed findings of archaeological research that the size and the position of the holes cannot be accidental — they were made with the intention of musical expression. The flute from Divje babe is the only one that was definitely made by Neanderthals. It is about 20,000 years older than other known flutes, made by anatomically modern humans. This discovery confirms that the Neanderthals were, like us, fully developed spiritual beings capable of sophisticated artistic expression. [Source: Narodni muzej Slovenije]

Divje babe cave lies below the north-eastern edge of the Šebrelje plateau, 230 meters above the Idrijca River. The cave in which it was found was a den of cave bears, but in the last glacial period it was occasionally also visited by people, initially Neanderthals and afterwards anatomically modern humans. The flute was found close to a hearth, in a layer deposited about 60 to 50 millennia ago. Based on the dating of the layer in which the flute was discovered, it is about 60,000-50,000 years old. In the layer with the flute, the archaeologists also discovered Neanderthals’ stone tools. The age of the layer in which the flute was discovered was established on the basis of electron spin resonance used on bear teeth found in the same layers as the flute.

The Neanderthal flute from Divje babe is he best evidence for the existence of music among Neanderthals. The find radically undermines until recently inveterate conceptions of Neanderthals as primitive hominids. It testifies to the fact that the Neanderthals were innovative and sensitive people capable of artistic expression.

Making and Shape of the Neanderthal Flute

How did the Neanderthals make the flute? With practical experiments with the replicas of the tools, discovered in the cave, archaeologists explained how the Neanderthals made the holes in the flute: with a pointed stone tool, a small hollow was carved in the bone, and it was pierced with a bone punch. The result was a hole. Various analyses and experiments proved the impossibility of the holes being attributed to animal bites or a coincidence.

The shape of the selected thighbone, its preserved length, a mouthpiece (deliberately sharpened edge at the top), and the results of CT scans allowed an accurate and authentic reconstruction of the instrument which allows a wide range of sonority in melodic movement. In terms of musical performance, the instrument is superior to the other reconstructed Palaeolithic musical instruments, and it is ergonomically adapted to a right-handed musician. You can enjoy the melodies masterly played by the academic musician Ljuben Dimkaroski on the reconstruction of the Neanderthal flute.

On the top side of the flute side, there are two complete holes (Holes 2 and 3 of the flute). Notch 1 (Hole 1 of the flute) is located near middle. The larger, semicircular notch (Notch 4 of the flute) is located at the distal end (farthest from the center). On the under side, another semicircular notch 5 (Hole 5 of the flute) is located near at the distal end. This notch is equivalently positioned longitudinally as is Hole 3 on the posterior side. Holes 2 and 3 are approximately the same size. Notches 1 and 5 are both the same size, but smaller than Holes 2 and 3. All the holes and notches are arranged in a line and have a similar morphology, except for the larger notch 4. [Source: Wikipedia]

Very Old Flutes From Germany

One flute made from the hollow bones of an ancient vulture in Germany was dated to be between 43,000 and 40,000 years-old, making it one of the oldest known musical instrument, and the among the earliest evidence for human creativity. According to Live Science: The flute fragment was found in in a cave in the Swabian Alps in southwest Germany. It has a V-shaped mouthpiece that produced a note when air was blown across it; the note could be varied by placing fingers on its five drilled holes. The archaeologists who found it speculate that playing music might have even given Homo sapiens an evolutionary edge over earlier human species, by improving their communications and creating tighter social bonds. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 24, 2019]

In June 2009, scientists from the University of Tübingen in Germany revealed the oldest-known musical instrument — a thin, 35,000-year-old, bird-bone flute — found in in southwestern Germany. Dating to around the time the earliest sculptures and cave painting appeared, the flute was made from a hollow bone from a griffon vulture. The preserved portion is about 8.5 inches long and includes the end of the instrument into which the musician blew. The maker carved two deep, V-shaped notches there, and four fine lines near the finger holes. The other end appears to have been broken off; judging by the typical length of these bird bones, two or three inches are missing. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, June 24, 2009]

Music made by ancient Chinese flutes Archaeologists discovered the five-finger-hole, bird-bone flute and two fragments of ivory flutes in the fall of 2008 at Hohle Fels Cave in the hills west of Ulm. They said, the flute was “by far the most complete of the musical instruments so far recovered.” In caves nearby a three-hole flute carved from mammoth ivory was uncovered, as well as two flutes made from the wing bones of a mute swan.

In an article published online by the journal Nature, Nicholas J. Conard of the University of Tübingen, in Germany, and colleagues wrote, “These finds demonstrate the presence of a well-established musical tradition at the time when modern humans colonized Europe.” The flutes were dated with radiocarbon dating, which can be imprecise with samples older than 30,000 years old. However the flutes and associated material were tested independently by two laboratories, in England and Germany, using different methods. Scientists said the data agreed on ages of at least 35,000 years.

, Many people appeared to have lived and worked in the cave where the flute was found. Dr. Conard’s team unearthed numerous stone and ivory artifacts, beautiful carvings of animals, flint-knapping debris and bones of hunted animals in the sediments with the flutes. Perhaps not coincidently just a few feet away from the flute a carved figurine of a busty, nude woman, also around 35,000 years old, was found.

In 2004, Conard discovered a the seven-inch three-hole ivory flute at the Geissenklösterle cave, also near Ulm. At the time he said southern Germany “may have been one of the places where human culture originated.” Friedrich Seeberger, a German specialist in ancient music, reproduced the ivory flute in wood and said it produced a range of notes comparable in many ways to modern flutes. “The tones are quite harmonic,” he told the New York Times. A replica of the vulture bone flute had not been made as 2009 but the archaeologists said they expected the five-hole flute with its larger diameter to “provide a comparable, or perhaps greater, range of notes and musical possibilities.”

Other Old Flutes

A number of flutes said to be even older than German ones have been found but the dates attached to them are not regarded as firm and reliable. Flutes made of animal bone found in France have been dated to between 43,000 and 35,000 years ago.. Scientists have speculated that they may have been made by Neanderthals and suggested their design was so sophisticated that been hundreds of thousands of flutes had to have been made before to get the design right. Patricia Gray, a professional keyboardist and the artistic director of the National Musical Arts, told the New York Times, "What you immediately hear when you play one of these flutes is the beauty of their sound, They make pure and rather haunting sounds in very specific scales.”

one of the world's oldest flute Among the ancient flutes that have been found are bone pipe from Wurttenberg, Germany, dated to be 38,000 years old. An Aurignacian period (about 40,000 to 28,000 years ago) period flute made from a naturally hollow bird bone with at least three finger holes was found at the site of Isturitz in southwestern France. At least dozen similar flutes have been dated to the Gravettian cultural period (roughly 28,000 to 22,000 years ago). The flutes played a scale similar to that played today.

Some scientists believe the flutes were made to produce accompanying music for cave paintings. In one experiment, researchers found that in caves where art has been discovered the rooms with the best acoustics were the ones that housed paintings. One cave with images of bison and horses produced an echo when hands were clapped that sounded like a stampede. A room that dampened sound contained stealthy creatures such as panthers.

Early Flutes in China

The oldest playable flute, a seven-holed instrument carved 8000 years ago from the hollow wing bone of a large bird, was unearthed in Jiahu, an archeological site in the Yellow River Valley in central China. The flutes were found in the late 1980s but were not described in the West until 1999. [Source: Zhang Juzhong and Lee Yun Kuem, Natural History magazine, September 2005]

Thirty-three flutes — including around 20 intact flutes and several broken or fragmented ones and several more unfinished ones — have been found at Jiahu. All are between seven and 10 inches in length and are made of wing bones from the red-crowned crane, a bird that stands five feet tall and has a wing span of eight feet and is famous for its courtship dance. It seems plausible that ancient flutes were also made from bamboo. Ancient myths described bamboo flutes but no ancient ones have been found in all likelihood because bamboo decays more quickly than bone and doesn’t survive burial for thousands of years like bone does.

The flutes were cut, smoothed at the ends, polished and finally drilled with a row of holes on one side. One of the broken flutes was repaired by drilling fourteen tiny holes along the breakage lines and then tying the section together with string.

The flutes were cut, smoothed at the ends, polished and finally drilled with a row of holes on one side. One of the broken flutes was repaired by drilling fourteen tiny holes along the breakage lines and then tying the section together with string.

The flutes have between five and eight holes. They play in the so-called pentatonic scale, in which octaves are divided into five notes — the basis of many kinds of music, including Chinese folk music and rock n' roll. The fact that the flute has a scale indicates that its original players played music rather than just single notes.

The flutes were probably used in some kind of ceremonial capacity but may have been played for entertainment. The flutes were found along with evidence early wine making (See Below), which suggests that the people who played them could have been a festive bunch.

Types of Flutes in China

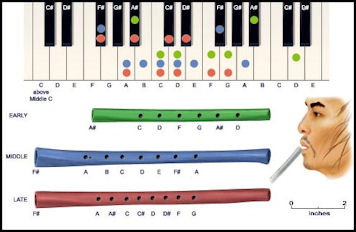

Archeologists have divided the flutes found in Jiahu into three groups: 1) the early phase, those between 9,000 and 8,600 years old; 2) the middle phase, those between 8,600 and 8,200 years old; 3) the late phase, those between 8,200 and 7,800 years old.

Only two flutes from the early phase were recovered, both from the grave of an adult male. One has five holes and can produce six distinct pitches. The other has five holes and can produce seven distinct pitches, including two notes repeated an octave apart.

About two dozen flutes from the middle phase were unearthed. Fifteen are intact or could be reconstructed. One has two holes. The others all have seven holes and can play eight pitches. Despite some difference in the range of pitches the intervals between them are similar.

Seven flutes from the late phase were unearthed. One of them can still played. These have eight holes and pitch intervals close together and are capable of a variety of melodic structures. A flute from the late phase found 80 miles from Jiahu in Zhinghanzhai has tens holes, staggered on two parallel lines with the intervals between them close to half steps.

Notes from the playable flute have been recorded and analyzed. The flute produces a rough scale covering the modern octave, beginning close to the second A above middle C, and appears to have been tuned — a tiny hole was drilled near the seventh hole, with effect of raising that hole's tone from roughly G-sharp to A, completing the octave.

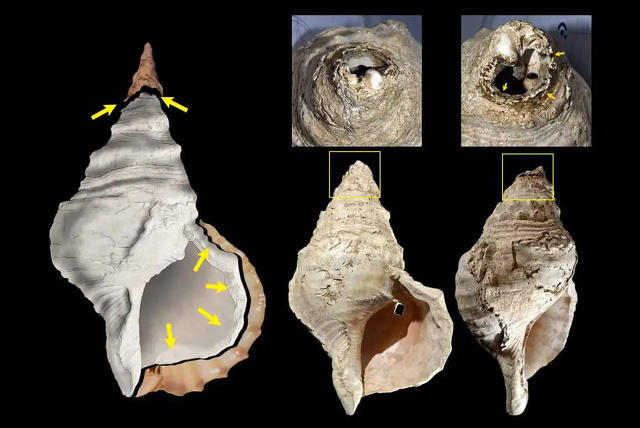

17,000-Year-Old Sea Shell Horn

A shell wind instrument dated to around 15,000 B.C. was found in Marsoulas Cave, France It was made from a ea snail shell (Charonia lampas) and measured (31 centimeters by 19 centimeters (12.2 inches by 7.5 inches), and weighed 1.2 kilograms (2.7 pounds), [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Everyone who lives or vacations near the ocean has gone on an early morning beach walk to collect shells and, thinking they have found a perfectly intact specimen, bent over and plucked it from the sand, only to find the top broken off, the bottom missing, or a crack in the side. In the case of this sea snail shell from Marsoulas Cave in France’s Pyrenees Mountains — the largest shell ever found in a European prehistoric context — what might first be perceived as damage was actually the product of precision artistry. Many millennia ago, a member of the Paleolithic Magdalenian culture made a musical instrument from the shell, creating what is now the oldest known shell wind instrument in the world. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

lThe shell was originally discovered in 1931 just outside the cave’s entrance. A photo of the shell was published the next year along with text identifying it as having no traces of human modification, explains archaeologist Gilles Tosello of the University of Toulouse. “It was thought of as a curiosity brought back by the Magdalenians from the coast and that it was probably used as a drinking cup,” he says. Nearly a century later, Tosello, along with a team of eight researchers directed by Carole Fritz, reexamined the shell, which had been stored in the Museum of Toulouse. Upon close study, he noticed tool marks establishing that deliberate modifications had, in fact, been made to the shell.“This shell has been waiting for ninety years for us to unlock its secrets,” says Tosello. “These modifications are very sophisticated.” So too was the music it made. A musicologist who specializes in horn playing was able to produce three deep, resonant notes — a C, a C-sharp, and a D — at about 100 decibels, more than loud enough to be heard at a distance from the mouth of the cave.

The discovery was reported in the journal Science Advances. Jonathan Amos of the BBC wrote: “The shell must have been a prized object because the coastline where it was presumably picked up or traded is more than 200 kilometers away. Its significance lies in the dot-like markings inside the shell. These match the artwork on the walls of the Marsoulas cave in the Pyrenees where the artefact was unearthed in 1931. “This establishes a strong link between the music played with the conch and the images, the representations, on the walls," explained Gilles Tosello from the University of Toulouse. "To our knowledge this is the first time we can put in evidence a relationship between music and cave art in European pre-history." [Source: Jonathan Amos, BBC, February 11, 2021]

The scientists have identified the deliberate modifications that would have enhanced the shell's ability to make sound. These include the hole excised at one end that would have permitted the insertion of some kind of mouthpiece, and cuts at the other end that would have made it easier to insert a hand to modulate the sound — in the same way a French horn player might insert their hand into the bell of the instrument to alter the pitch. The team asked a professional musician to blow into the conch. “The intensity produced is amazing, approximately 100 decibels at one meter. And the sound is very directed in the axis of the aperture of the shell," said Philippe Walter from Sorbonne University.

Both ends of the conch were modified Image processing enhancements were used to study the patterns painted on the inner-surface of shell's opening. These patterns, made with an iron oxide pigment (red ochre), take the form of fingerprints. The walls of Marsoulas cave share this style. There is a bison picture, for example, traced out by 300 finger dots.The researchers have produced a 3D printed replica of the shell so they can further explore the musical possibilities of the conch without the risk of damaging the original artefact.

“The Upper Palaeolithic people who owned the shell were part of what archaeologists call the Magdalenian tradition, which was notable for its particular approach tool-making and use of bone, antler and ivory. It's also known the communities of the Pyrenees would interact with similar communities in Cantabria, coastal northern Spain. The conch reinforces this relationship. “The sound of this conch is a direct link with Magdalenian people," said Carole Fritz from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

Lithophones

Lithophones are xylophone-phone like musical instruments made from stones. Describing some at the Natural History Museum in Paris, Mariette Le Roux and Laurent Banguet of AFP wrote: “The instruments, carefully crafted stone rods up to a metre (3.2 feet) in length, have been in the museum's collection since the early 20th century. They have been dated to between 2500 and 8000 B.C., a period known as the New Stone Age, characterized by human use of stone tools, pottery-making, the rise of farming and animal domestication. [Source:Mariette Le Roux, Laurent Banguet, AFP, March 17, 2014 \=/]

Lithophone at a museum in Berlin

“For decades, their solid, oblong shape made experts believe they were pestles or grinders of grain. But that perception changed a decade ago, thanks to a stroke of fortune. Music archaeologist Erik Gonthier of the Natural History Museum, a former jeweller and stone-cutter, discovered their true, musical potential when he tapped one with a mallet in the storeroom of the museum in 1994. Instead of a dull thud he heard musical potential, and decided to investigate further. "I thought back to my grandmother's piano and the small supports which made the strings resonate. "I found some packaging foam in the trashcans of the museum I made two rests that I placed under either end of the lithophone, and tapped it. It made a clear 'tinnnnggg,'" Gonthier recounted. "My heart beat like crazy. I knew that I had found something great." \=/

“The museum's lithophones are mainly from the Sahara, many brought back by French troops stationed in colonies such as Algeria and Sudan in the early 1900s. Gonthier says all lithophones, which can be made from types of sandstone, share certain characteristics. Every instrument has two sound "planes" that can be found by tapping at 90 degree angles around its circumference. To play, the instruments would have been rested on brackets made of leather or plant fibres, or even on the musician's ankles, sitting cross-legged, said Gonthier. \=/

“Music may not have been the only purpose of the instruments. They may also have been used to signal danger, "or even to call people to dinner," said Gonthier. "They could be heard from kilometres (miles) away in the desert or forest". One thing is clear: "They were made to last – the proof is that we still have them today." \=/

Prehistoric Lithophone Played at Paris Concert

In 2014, the French National Orchestra performed three concerts showcasing the lithophones. Mariette Le Roux and Laurent Banguet of AFP wrote: “Thousands of years after they resonated in caves, 24 stone chimes used by our prehistoric forefathers will make music once more in a unique series of concerts in Paris....The instruments have been dusted off from museum storage to be played in public for the first time to give modern humans an idea of his ancestral sounds. After just three showsthe precious stones will be packed away again, forever. "That will be their last concert together," Gonthier told AFP ahead of the production. "We will never repeat it, for ethical reasons – to avoid damaging our cultural heritage. We don't want to add to the wear of these instruments." [Source: Mariette Le Roux, Laurent Banguet, AFP, March 17 2014 \=/]

“Crucially, the instruments are short and slim enough to be carried easily in one hand - the earliest example of a portable sound system. "Dubbed "Paleomusique", the piece was written by classical composer Philippe Fenelon to showcase the mineral clang and echo of instruments from beyond recorded time. \=/ “They will be played 'xylophone-style' by four percussionists from the French National Orchestra gently tapping the stones with mallets. The point is to highlight our ancestors' musical side, which Gonthier says is often overshadowed by their rock-painting and tool-making prowess. In fact, he believes, there might have been a strong link between music and visual art in prehistoric caves. "These were the first theatre or cinema halls," he speculated. \=/

Were Paleolithic Caves Chosen to Produce Sounds and Music?

Douglas Starr wrote in Discover magazine: “Some of the first research on the importance of acoustics to prehistoric peoples was done by Iegor Reznikoff, an anthropologist of sound at Université Paris Ouest, who in the 1980s visited cave paintings and carvings in southern France that are about 25,000 years old, among the oldest known human art. A number of them are so far underground that scientists were puzzled as to why anyone would have gone there. Reznikoff, who has a habit of humming whenever he enters a space, noticed that in parts of the caves, his voice resonated as effectively as in any cathedral. He and a colleague mapped several caves and found that areas with the greatest resonance coincided with the concentration of artworks. [Source: Douglas Starr, Discover, September 26, 2012 -]

“Further evidence for the connection between art and sound came from Steven J. Waller, a biochemist and avocational archaeologist from California. Waller knew that echoes played a role in many ancient myths, such as Native American tales of sprites who speak through portals in rock walls. In 1994 he conducted an acoustical survey of Horseshoe Canyon, a three-mile-long chasm in southeastern Utah decorated with eerie pictographs. Waller hiked the canyon, pausing at 80 locations to snap a noisemaker fashioned from a rat trap and record the echoes. After processing the results with sound analysis software, he found that five spots displayed powerful echo effects. Four corresponded to the locations of paintings that Waller had encountered. When he asked experts about the fifth, they explained that it, too, bore artwork, though the pictographs were not visible from the path he had followed. Since then, Waller has repeated the experiment at hundreds of rock art sites around the world, almost always finding a correlation between image and echo. He speculates that ancient artists “purposely chose these places because of sound.” -

“Such findings suggest that ancient people created artworks in response to acoustics; others hint that they may even have built structures to control it. For example, El Castillo pyramid in Mexico, built by the Mayans some 1,100 years ago, bears four stepped sides, each vertically bisected by a staircase. If you clap your hands at the pyramid’s base, you hear a series of chirps. Locals near similar pyramids have long compared the sound to the cry of the quetzal, a bird venerated by the Mayans. In the 1990s acoustician David Lubman recorded the hand-clap echoes at El Castillo and compared them with recordings of the quetzal. He found that recordings and sonograms of several echoes really do match the bird’s cry. Lubman says the echo “is a powerfully robust phenomenon” unlikely to have resulted by accident. -

Playing a lithophone in Spain in 1905

“The most detailed evidence of ancient acoustical design comes from the Stanford team studying Chavín de Huántar, which was constructed between 1300 and 500 B.C. Peruvian archaeologists first suspected the complex had an auditory function in the 1970s, when they found that water rushing through one of its canals mimicked the sound of roaring applause. Then, in 2001, Stanford anthropologist John Rick discovered conch-shell trumpets, called pututus, in one of the galleries. The team set out to determine what role the horns played in ancient rituals and how the temple may have heightened their effects.

Archaeoacoustics researcher Miriam Kolar and her collaborators played computer-generated sounds to identify which frequencies the temple most readily transmits. Over years of experiments, they found that certain ducts enhanced the frequencies of the pututus while filtering out others, and that corridors amplified the trumpets’ sound. “It suggests the architectural forms had a special relationship to how sound is transmitted,” Kolar says. The researchers also had volunteers stand in one part of the temple while pututu recordings played in another. In some configurations, the sound seemed to come from all directions. Kolar believes the combination of instrument and architecture may have been used to create a mystical experience. She asserts that the totality of evidence—including carvings showing celebrants with eyes upturned and bodies shape-shifting into half-animal forms—indicates a spiritual intent.” -

Image Sources: AFP, Natural History magazine

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024