Home | Category: After Alexander the Great / Culture and Sports / Art and Architecture

ALEXANDRIA

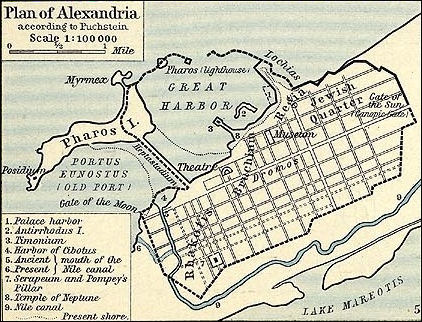

Alexandria today is Egypt's second largest city and the country's largest port. In the time of the ancient Egyptians it wasn’t even built yet. But in the Greco-Roman era it was one of the greatest cities of antiquity. Regarded as the greatest intellectual center in the world, it was home to the great Alexandria Library and the Pharos Lighthouse, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Chip Brown wrote in National Geographic, It was in Alexandria, “18 centuries before the Copernican revolution, that Aristarchus posited a heliocentric solar system and Eratosthenes calculated the circumference of the Earth. Alexandria was where the Hebrew Bible was first translated into Greek and where the poet Sotades the Obscene discovered the limits of artistic freedom when he unwisely scribbled some scurrilous verse about Ptolemy II's incestuous marriage to his sister. He was deep-sixed in a lead-lined chest.” [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011]

Websites: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Alexandria: The City that Changed the World” by Islam Issa (2023) Amazon.com;

“Alexandria: A History and a Guide” by E.M. Forster - Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Alexandria: Birthplace of the Modern World”

by Justin Pollard and Howard Reid (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pharos - A Lighthouse For Alexandria” by Thomas C. Clarie (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Pharos Lighthouse In Alexandria: Second Sun and Seventh Wonder of Antiquity (Routledge) by Andrew Michael Chugg (Author) Amazon.com;

“The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World” by Bettany Hughes (2024) Amazon.com;

“How the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Were Built” Picture Book by Ludmila Henkova (Author), Tomas Svoboda (Illustrator) (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Library and Lighthouse of Alexandria” (A Wonders of the World Book)

by Jimmy Maher (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World” by Roy MacLeod | (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Beacon at Alexandria” by Gillian Bradshaw (1986), Novel Amazon.com;

“Alexandria & the Sea: Maritime Origins and Underwater Explorations” by Kimberly Williams (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Mosaics of Alexandria: Pavements of Greek and Roman Egypt” by Anne-Marie Guimier-Sorbets and Colin Clement (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” by Toby Wilkinson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ptolemy I: King and Pharaoh of Egypt,” Illustrated, by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Last Pharaohs: Egypt Under the Ptolemies, 305–30 BC” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies” by Guy de la Bedoyere (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ptolemies Volume 1: Rise of a Dynasty: Ptolemaic Egypt 330–246 BC” by John D Grainger(2022) Amazon.com;

“Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs” by Paul Edmund Stanwick (Author Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff (2010) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Diane Stanley (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

Ptolemies

After the death of Alexander the Great, the Egyptian portion of his kingdom was ruled Ptolemy I, a Macedonian general. The Macedonian-Greek dynasty (the Ptolemies) he founded ruled Egypt for more than 300 years. There were 15 Ptolemic leaders and they ruled from 332 B.C. to 30 B.C. from Alexandria. Cleopatra was the last of Ptolemies. When she died in 30 B.C., Romans took over territory formally controlled by the Ptolemies.

Chip Brown wrote in National Geographic, “The Ptolemies of Macedonia are one of history's most flamboyant dynasties, famous not only for wealth and wisdom but also for bloody rivalries and the sort of "family values" that modern-day exponents of the phrase would surely disavow, seeing as they included incest and fratricide. [Source: Chip Brown, National Geographic, July 2011]

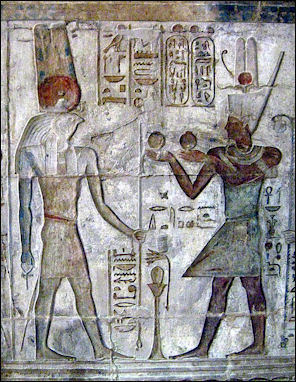

Menthu and Ptolemy IV The Ptolemies came to power after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great, who in a caffeinated burst of activity beginning in 332 B.C. swept through Lower Egypt, displaced the hated Persian occupiers, and was hailed by the Egyptians as a divine liberator. He was recognized as pharaoh in the capital, Memphis. Along a strip of land between the Mediterranean and Lake Mareotis he laid out a blueprint for Alexandria, which would serve as Egypt's capital for nearly a thousand years.

The dynasty's greatest legacy was Alexandria itself, with its hundred-foot-wide main avenue, its gleaming limestone colonnades, its harborside palaces and temples overseen by a towering lighthouse, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, on the island of Pharos. Alexandria soon became the largest, most sophisticated city on the planet. It was a teeming cosmopolitan mix of Egyptians, Greeks, Jews, Romans, Nubians, and other peoples. The best and brightest of the Mediterranean world came to study at the Mouseion, the world's first academy, and at the great Alexandria library.

The Ptolemies' talent for intrigue was exceeded only by their flair for pageantry. If descriptions of the first dynastic festival of the Ptolemies around 280 B.C. are accurate, the party would cost millions of dollars today. The parade was a phantasmagoria of music, incense, blizzards of doves, camels laden with cinnamon, elephants in golden slippers, bulls with gilded horns. Among the floats was a 15-foot Dionysus pouring a libation from a golden goblet.

See Separate Article on the Ptolemies

Alexander the Great Founds Alexandria

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Alexander's military campaign was the founding of Alexandria. Arrian wrote that "he himself designed the general layout of the new town, indicating the position of the market square, the number of temples...and the precise limits of its outer defenses." After Alexander died, Alexandria grew into the center of Hellenistic Greece and was the greatest city for 300 years in Europe and the Mediterranean.

Plutarch wrote: “For when he was master of Egypt, designing to settle a colony of Grecians there, he resolved to build a large and populous city, and give it his own name. In order to which, after he had measured and staked out the ground with the advice of the best architects, he chanced one night in his sleep to see a wonderful vision; a grey-headed old man, of a venerable aspect, appeared to stand by him, and pronounce these verses: “An island lies, where loud the billows roar, Pharos they call it, on the Egyptian shore." Alexander upon this immediately rose up and went to Pharos, which, at that time, was an island lying a little above the Canobic mouth of the river Nile, though it has now been joined to the mainland by a mole. As soon as he saw the commodious situation of the place, it being a long neck of land, stretching like an isthmus between large lagoons and shallow waters on one side and the sea on the other, the latter at the end of it making a spacious harbour, he said, Homer, besides his other excellences, was a very good architect, and ordered the plan of a city to be drawn out answerable to the place. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

Alexandria laying out his plan for Alexandria

"To do which, for want of chalk, the soil being black, they laid out their lines with flour, taking in a pretty large compass of ground in a semi-circular figure, and drawing into the inside of the circumference equal straight lines from each end, thus giving it something of the form of a cloak or cape; while he was pleasing himself with his design, on a sudden an infinite number of great birds of several kinds, rising like a black cloud out of the river and the lake, devoured every morsel of the flour that had been used in setting out the lines; at which omen even Alexander himself was troubled, till the augurs restored his confidence again by telling him it was a sign the city he was about to build would not only abound in all things within itself, but also be the nurse and feeder of many nations. He commanded the workmen to proceed, while he went to visit the temple of Ammon."

Arrian wrote: “The following story is told, which seems to me not unworthy of belief:—that Alexander himself wished to leave behind for the builders the marks for the boundaries of the fortification, but that there was nothing at hand with which to make a furrow in the ground. One of the builders hit upon the plan of collecting in vessels the barley which the soldiers were carrying, and throwing it upon the ground where the king led the way; and thus the circle of the fortification which he was making for the city was completely marked out. The soothsayers, and especially Aristander the Telmissian, who was said already to have given many other true predictions, pondering this, told Alexander that the city would become prosperous in every respect, but especially in regard to the fruits of the earth. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“At this time Hegelochus sailed to Egypt and informed Alexander that the Tenedians had revolted from the Persians and attached themselves to him; because they had gone over to the Persians against their own wish. He also said that the democracy of Chios were introducing Alexander's adherents in spite of those who held the city, being established in it by Autophradates and Pharnabazus. The latter commander had been caught there and kept as a prisoner, as was also the despot Aristonicus, a Methymnaean, who sailed into the harbour of Chios with five piratical vessels, fitted with one and a half banks of oars, not knowing that the harbour was in the hands of Alexander's adherents, but being misled by those who kept the bars of the harbour, because forsooth the fleet of Pharnabazus was moored in it. All the pirates were there massacred by the Chians; and Hegelochus brought to Alexander, as prisoners Aristonicus, Apollonides the Chian, Phisinus, Megareus, and all the others who had taken part in the revolt of Chios to the Persians, and who at that time were holding the government of the island by force. He also announced that he had deprived Chares of the possession of Mitylene, that he had brought over the other cities in Lesbos by a voluntary agreement, and that he had sent Amphoterus to Cos with sixty ships, for the Coans themselves invited him to their island. He said that he himself had sailed to Cos and found it already in the hands of Amphoterus. Hegelochus brought all the prisoners with him except Pharnabazus, who had eluded his guards at Cos and got away by stealth. Alexander sent the despots who had been brought from the cities back to their fellow-citizens, to be treated as they pleased; but Apollonides and his Chian partisans he sent under a strict guard to Elephantinē, an Egyptian city."

History of Alexandria in the Greco-Roman Period

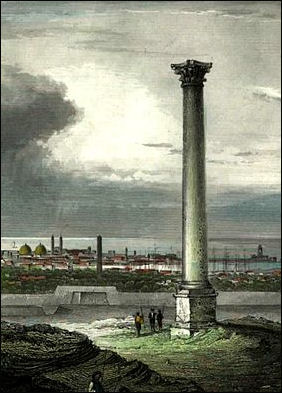

Alexandria Pompey Pillar Founded by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C., Alexandria was the greatest city in Mediterranean in its day, eclipsing even Athens and Rome. At its peak it was the home to 600,000 people and boasted temples and places that stretched from the Gate of the Moon to the Gate of the Sun. It hosted a Dionysian festivals that featured a 180-foot-high golden phallus, 2,000 golden-horned bulls and a gold statue of Alexander carried by elephants.

Regarded by some as the first true metropolis, Alexandria was multi cultural capital of Greco-Roman (Ptolemaic) Egypt, the center of a rebirth of Greek culture (known today as the Hellenistic period), the site of Cleopatra's stormy relationships with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, and a center of Jewish culture and early Christians thinkers.

Alexander chose Alexandria for a port by while traveling on the Mediterranean coastline from Syria to Egypt. He wanted to link the Mediterranean with the Nile and picked Alexandria’s general location because of its magnificent harbor and chose to set up the city 30 kilometers to the west of the Nile on spit of land between a the sea and a lake because he realized that the Mediterranean's west-to east-currents would prevent Nile silt from accumulating there. A canal was built the Nile to bring freshwater and provide transport. Greek engineers designed an effective wave break by building a pier between the mainland the island of Pharaohs. Alexandria grew by supplying papyrus, jewels, glass and grain to the Greeks and Romans.

Alexandria flourished under the Ptolemaic Greeks who built the Light of Pharos, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, and the Library of Alexandria, the world's first great library and academic center. It also became a major trading center for goods such as silk, spices and aromatic plants , ebony and ivory tusks brought from Africa and the maritime and overland Silk Roads. Theaters, bordellos and halls emerged. Jews were give their own quarter. They mingled with Egyptians, Christians, Greeks, Phoenicians, Nabateans, Arabs and Nubians. Cleopatra was the last of the Ptolemaic rulers and after she committed suicide the city was taken over by Romans.

Alexandria declined as a Mediterranean superpower and was eclipsed by Rome after the suicide of Antony and Cleopatra in 30 B.C. During the Roman period Alexandria was most important center of Christianity in the world until the 4th century when large numbers of Christians were slaughtered under the rule of the Roman emperor Diocletian.

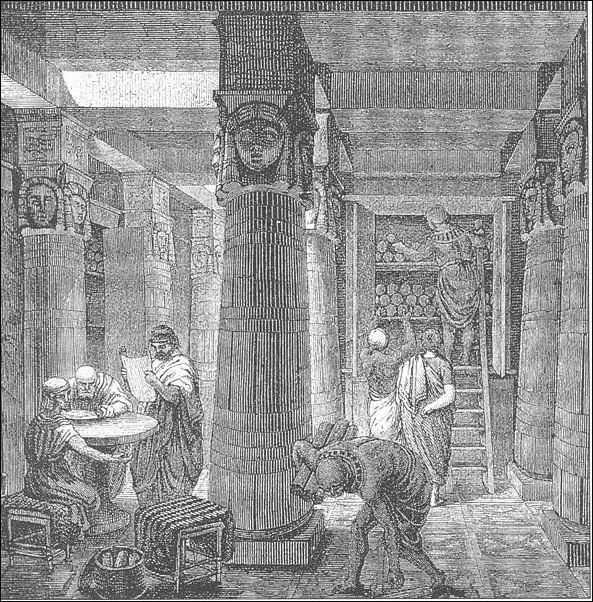

Alexandria Library

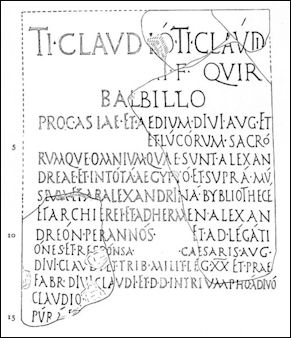

Alexandria Library Inscription The great library of Alexandria was “first ample repository of the west's literary inheritance." It was inaugurated by in 298 B.C. Ptolemy I. According to legend Alexandria the Great envisioned a great library but it was Ptolemy I who proposed collecting “books of all the peoples of the world.” He sent letters to rulers in the known world and asked them for works by “poets, and prose-writers, rhetoricians and sophists, doctors and soothsayers, historians.” "Ptolemy II enlarged the library, adding a museum and research center. [Source: Alexander Stille, New Yorker, May 8, 2000, Lionel Casson, Smithsonian Magazine.

Before the establishment of the Alexandria Library, most book collections belong to private owners. Aristotle and Alexander the Great supposedly had large libraries. Libraries were not a new idea. The Egyptians built papyrus libraries in 3200 B.C. and Athens had a library in the 4th century. But the size and scope of the Alexandria Library was on a scale the world had never seen.

Probably modeled on the Lyceum, Aristotle’s library and school in Athens, the Alexandria Library was located in the Mouseion, the Temple of Muses. No one knows exactly where that was except that it was part of the Royal Court of the Ptolemy, a huge complex that covered a large area and included a zoo and botanical gardens.

According to Strabo, who visited Alexandria in 20 B.C., the library "was part of the royal palaces, it had a walk, an arcade, a large house in which was a refractory for members of the Mouseion."

The great library of Alexandria was an ancient think tank, a meeting place for scholars from throughout the known world. Scholars lived together in a communal residence and ate together in a dining hall. Among their achievement was creating Euclidian geometry, performing the first dissections of human bodies, translating the Hebrew Bible into Greek, and compiling Homer's epic poems.

Around 200 B.C. a large library was established in Pergamum on Asia Minor that competed with the Alexandria library to get its hands on the best books. The family that inherited Aristotle's collection reportedly hid all their books when their town was ruled by Pergamom. Eventually the Pergammon collections was transferred to Alexandria when Antony gave Cleopatra Asia Minor as a gift.

Alexandria Library Book: “ The Vanishing Library: A Wonder of the Ancient World” by Luciano Canfora.

World’s First University in Alexandria?

Before the library was built in Alexandria, Ptolemy I founded the Mouseion, a research institute which some regard as the world’s first university. It had lecture halls, laboratories and guest rooms for visiting scholars. Archimedes, Aruistarchus of Samos and Euclid all worked there. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Smithsonian magazine, April 2007]

Ptolemy II and Jews Excavations in downtown Alexandria in the 1990s and 2000s revealed lecture halls from the Mouseion. The area that has been reconstructed thus far shows a row of rectangular halls. Each has a a separate entrance into the street and horse-shoe-shaped stone bleachers. The neat rows of rooms lie in a portico between the Greek theater and the Roman baths. The facilities were built about A.D. 500.

Grzegorz Majcherek. A Polish archaeologist from Warsaw University who is working the site, told Smithsonian magazine, he believes the rooms and hall “were used for higher education — and the level of education was very high.” Texts in other archives show that professors were well paid with public funds and they were forbidden from teaching private lessons except on their days off. There is also evidence that both Christian and pagan scholars worked there.”

Perhaps similar institutions existed in Antioch, Constantinople, Beirut or Rome but no evidence of them has turned up. Majcherek believes Mouseion may have attracted many scholars from the Athens Academy, which closed in A.D. 529. There is some evidence that intellectual activity continued after the arrival of Islam in the 7th century but things later quieted down and likely shifted to Damascus or Baghdad.

See Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum Under Philosophy and Science

Contents of the Alexandria Library

The Alexandria Library boasted it had a copy of every known manuscript. It probably contained about a 490,000 scrolls. Scholars debate whether 490,000 scrolls represented 490,000 individual works or the total number of scrolls. Many works contained multiple scrolls. The 24 books of Homer's “ Odyssey” , for example, was probably represented by 24 scrolls. It there were duplicates it may have contained 700,000 or copies. It was rivaled only by the Perguman library which had 200,000 scrolls.

The library was filled with scribes. Books and scrolls were brought form all over the known world. Ships that entered the harbor at Alexandria were stripped of their books. The books were taken to the library, where they were copied. The copies were returned to the ships, with the originals being kept in the library. [Source Ward Hazell, Listverse, August 31, 2019]

Most of the books in the Alexandria Library were written on foot-wide, 20-feet-long scrolls. Many were written on both sides and on average one scroll contained the equivalent of sixty pages of text from a modern book. Books were collected from leaders in the known world. The Athenians were tricked into handing over a stash of major Greek tragedies and paid a fortune for library said to belonging to Aristotle. Many new works were obtained from ships anchored in the city's harbor, which were required to hand over books to the library which were copied as "special rapid-copying shops." Sometimes the libraries officials kept the original and gave the owner back a copy.

The Alexandria Library is believed to be one of the first places where books were arranged in alphabetical order by author’s last name, and authoritative text editions, glossaries and indexes were kept. The scrolls were kept in warehouses and shelf-lined rooms, often stored in bucket-like containers.

Alexandria Library as an Intellectual Center

The Alexandria Library also contained a museum, or literally "a Place of Museum." Unlike a modern museum it was gathering places for scholars and intellectuals. According to one classics professor, "it had a dining hall in which they took their meals in common, private studies, laboratories, a cloisterlike promenade for thoughtful strolling, and so forth, all funded by generous endowment from the crown." Strabo wrote, "They formed a community who held property in common with priest appointed by the kings."

Among the great minds who worked there were the mathematicians Eratosthenes and Euclid, the physicists Archimedes, the poet Theocritus and, and the philosophers Zeno and Epicurus. Euclid completed his famous “ Elements” at the library. Eratosthenes, who made his famous measurement of earth's circumference, worked as a librarian of the library. Others worked out the principal of the steam engine, dissected human bodies and worked out the brain was the center of the nervous system and intelligence.

Alexandria Library

The Alexandria Library was "the seedbed of the ancient Greek Renaissance.” Scholars there mapped the stars and planets, created geometry, came up with the idea of the "leap years," revived Plato and Aristotle, translated works by Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, and collected Buddhist, Jewish and Zoroastrian texts. “ Greek Grammar” by Dionysus Thrax was used as a guide to grammar and style until the 12th century.

One of the greatest achievements was the essential creation of the Old Testament by seventy-two Jewish scholars, when they translated the Hebrew Bible (the Torah), "which from its beginning was enshrouded in legend and folklore," into Greek. The scholars were brought together by Ptolemy I. According to a Jewish legend, he asked each of the Jewish scholars individually to translate the whole Hebrew Bible and miraculously the result, was 72 identical versions. Modern copies of the Bible are all based on the Greek translation.

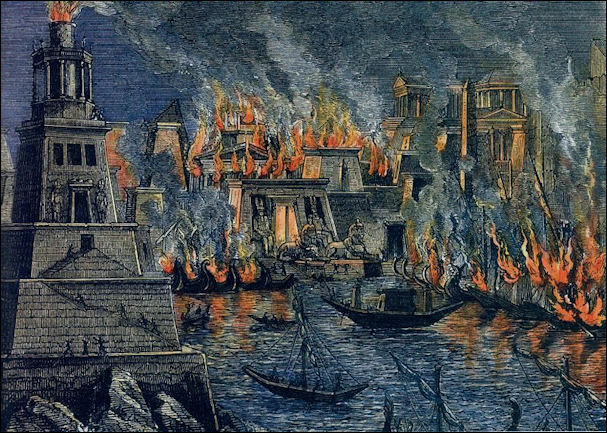

Burning of the Alexandria Library

The loss of the contents of the Alexandria Library by a massive fire is regarded by some as the worst intellectual tragedy ever. All that remains today are fragments and copies that appeared on later texts. Scholars still debate how the Alexandria Library came to a fiery end. Many believed the some of scrolls were destroyed in a fire in 48 B.C. and the library itself was destroyed by Christians in A.D. 391.

Some blame Caesar. Both Seneca and Plutarch wrote that Caesar set fire to boats during his conquest of Alexandria in 48 B.C. According to Seneca the fire spread and 40,000 scrolls were destroyed. He said these scrolls were in the warehouse. Even if they were part of the library, they were only a fraction of the total collection.

Some blame early Christian who went on a campaign against paganism in A.D. 391 under the Roman-Byzantine Emperor Theodosius. The Christians smashed idols, destroyed the Temple of Serapis and terrorized Alexandria’s intellectual community in a way that brings to mind the way the Taliban act in Afghanistan. In A.D. 415 Christian kidnapped and tortured to death the female philosopher and mathematician Hypatia, regarded as one greatest thinkers of her time. However there is no record of anything happening to the library.

Alexandria Fire by Hermann Goll (1876)

Others say it was the Arabs who destroyed the library when they conquered Egypt in the 7th century. According to one account, the Arabs entered Alexandria and used 700,000 books from the famous library to kindle fires in the city's 4,000 public baths because they contained "matter not in accord with the book of Allah." The problem with the account is that it was written 600 years after the purported event happened. A 7th century letter form a Muslim conqueror to the Muslim caliph, cited in the account, reportedly asks what to do with all the books. The caliph answered: “As for the book you mention, if what was written in them agrees with the book of God, they are not required; if it disagrees, they are not desired. Destroy them therefore.”

It is likely that most of the scrolls just withered away. The idea that the entire library was destroyed in a single catastrophic event is probably inaccurate. Even if there was no fire, the scrolls would probably not survived for centuries because they were mostly written on papyrus, a very fragile, perishable material. There are virtually no remains from other great ancient libraries in Pergamun, Athens and Rome. The Dead Sea scrolls and papyrus texts from ancient Egypt have survived because they were placed in containers and stored in caves or tombs in very dry places.

Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse of Alexandria (sometimes called the Pharos of of Alexandria) may located on the site occupied by the Fortress of Qait Bay in modern Alexandria. One of the Seven Wonders of the World, it was originally named after the maritime god Pharos and was built on a small island off the coast of Alexandria in 280 B.C., about 40 years after Alexander the Great's death by Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II.

Towering over the port city founded by Alexander the Great, the Lighthouse of Alexandria stood taller than 107 meters (350 feet) and was adorned with giant pink granite statues, representing the Ptolemaic pharaohs and their queens. The corners of the upper floors were adorned with six figures of Tritons forged in metal. [Source Eva Tobalina, National Geographic History, December 28, 2021]

The Lighthouse of Alexandria was the forerunner to modern lighthouses. Guiding Mediterranean ships into Alexandria’s harbor from the third century B.C. until the Middle Ages. it lit the entrance to Alexandria harbor with a massive flame at its crest and was almost as high as the pyramids and had three stories and maybe as many as 300 rooms.No one is sure what it looked like. There are etching, a few representations in mosaics, paintings and glass but most of them were made long after it collapsed.

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, according to some descriptions, was made of white marble and massive blocks of white limestone,which would have shined brightly in the Egyptian sun. Th building was constructed of alternating circular and square tiers, each of which had a balcony. At the top was a small octagonal section and a cylindrical section with a seven-meter (22-foot) tall bronze statue of the god Poseidon or Zeus. The light was reportedly provided by a great brazier surrounded by mirrors that reportedly could amplify the light from the fire so that it could seen 480 kilometers (300 miles) away at sea. This is no doubt a great exaggeration. The light warned ships of reefs and sand near Alexandria and showed the best way to approach the harbor.

Half the tower was torn down during Arab invasions of the 7th and 8th century. Weakened over the centuries, the remaining half collapsed into the sea in a great earthquake in 1375. Later it covered with Mamluk fortress. Virtually nothing remains of it today. The island on which it was located is now joined to the Alexandria mainland. The Alexandria Naval Museum has a model of the famous lighthouse. Ptolemaic lighthouses west of Alexandria are reputed to be models of the Pharos original.

There are at least six plans on the drawing board to recreate the lighthouse. In September 1998, Pierre Cardin announced plans to build a 400-foot-high fluorescent obelisk near the site of the old Alexandria lighthouse in Egypt. Costing $86.2 million, it was to be made of concrete covered with mirrored glass and 16,500 computer-controlled lights and lasers that would cast a beam 80 kilometers (50 miles) out to sea.

Ancient Lighthouses and Alexandria

Eva Tobalina wrote in National Geographic History: Bonfires lit along strategic coastal points have been documented since the first millennium B.C. Pirates known as “wreckers” used these fires to misdirect ships onto rocks and shoals and would then scavenge the cargo. The oldest structures considered lighthouses stood on the Greek island of Thassos in the fifth century B.C. After the Lighthouse of Alexandria was built in the third century B.C., lighthouses became popular. When Rome ruled the Mediterranean, lighthouses appeared from Ostia, Messina, and Ravenna (in Italy) to far off Dover, England. One of the best-preserved Roman lighthouses is in present-day A Coruña, Spain. Called the Tower of Hercules today and a UNESCO World Heritage site, it was known as the Farum Brigantium when it was built during the late first century A.D. [Source Eva Tobalina, National Geographic History, December 28, 2021]

Alexandria was shaped almost like a perfect rectangle between the sea and Lake Maryut. Contemporary travelers compared it to a chlamys, an ancient Greek cloak. The city received its water supply via a canal connecting it with the Canopic branch of the delta, and its sewers and wide avenues were a rarity in the eastern Mediterranean. The wondrous city was divided into five districts, but nearly a quarter of its extension was occupied by the palaces and gardens of royal enclosures.

The port was deep, making it suitable for ships with big draft, and the harbor was protected from dangerous northern winds by a string of islands. Still, without compass or navigational instruments, it was challenging to find one’s bearings by observing the coastline: In the area around the Nile Delta, there are no mountains or cliffs—the coast is an endless landscape of marshes and deserts, and the land is so low that it sometimes seems to be hiding behind the sea.

Another treacherous natural element was a great strip of barely submerged land, invisible to anyone unfamiliar with the coastal waters. Many sailors found that just when they thought the worst part of their journey was over, their ships would become stranded on this stretch of sand. A final hurdle was the double line of reefs in front of Alexandria, which could prove fatal to sailors and incoming ships if the winds weren’t favorable. Clearly a lighthouse was necessary, but not just any lighthouse would do.

Building the Lighthouse of Alexandria

Eva Tobalina wrote in National Geographic History: The placement of the lighthouse was carefully selected. Off the coast of Alexandria was a small island, Pharos. It was celebrated in Greek culture, since it was in Pharos that Menelaus—one of the Greek warriors of The Iliad and The Odyssey—was stranded on his return from the Trojan War. According to Plutarch, Homer himself had appeared in Alexander’s dreams, to quote his own lines about the island: “Now, there’s an island out in the ocean’s heavy surge, well off the Egyptian coast—they call it Pharos . . . There’s a snug harbor there.” When Alexander awoke, he looked for the island and, upon finding it, said that the ancient poet was “not only admirable in other ways, but also was a very wise architect.”[Source Eva Tobalina, National Geographic History, December 28, 2021]

In the westernmost part of the island, an islet, barely separated from Pharos by the sea, was selected for the new building. The lighthouse tower was a singular structure—the first of its kind erected by any civilization. It took the name of the neighboring island, and that is how the word pharos came to mean “lighthouse” in Greek (with Spanish and Italian borrowing it in their faro).

The founder of the Greek dynasty of Egypt’s pharaohs, Ptolemy I Soter, initiated building Alexandria’s lighthouse. Ptolemy I was a Macedonian nobleman who gained control of Egypt in the aftermath of Alexander’s death in 323 B.C. The project was completed during the reign of his son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus. According to Pliny the Elder, the Roman historian, one of these Ptolemies was generous enough to allow the name of the architect, Sostratus of Cnidus, “to be inscribed on the very fabric of the building.” Lucian, a writer from the second century A.D., had a more devious—and fanciful— explanation: “After he had built the work, he wrote his name on the masonry inside, covered it with gypsum, and having hidden it, inscribed the name of the reigning king. He knew, as actually happened, that in a very short time the letters would fall away with the plaster and his name would be revealed.”

Use of the Lighthouse of Alexandria

Eva Tobalina wrote in National Geographic History: The building, like so many of the constructions erected by the first Ptolemaic pharaohs, was magnificent. Pliny noted that it cost 800 talents (about 23 tons of silver) to build—about a tenth of the king’s entire treasury. By comparison, the Parthenon, built a century and a half before the lighthouse, cost roughly 469 talents. [Source Eva Tobalina, National Geographic History, December 28, 2021]

The lighthouse served its purpose perfectly: During the day, sailors could use it to navigate; at night, they could safely spot the harbor. Standing more than 350 feet tall, the lighthouse could be seen from 34 miles away—a whole day’s sailing—according to the Jewish historian Josephus. The fire burning at the summit of the lighthouse was so bright that it could be mistaken for a star in the dark. During the day, the smoke alone made it visible from a great distance. Wood was scarce in Egypt, leading many scholars to believe the fire was fueled by oil or papyrus.

It also seems probable that a large, burnished metal plank, or perhaps some kind of glass, was installed to act as a mirror, reflecting the glow of the flame. In medieval times, Arab authors, fascinated by the building, would fantasize that the mirror was in fact used like a magnifying glass, to harness and direct the power of the sun against any enemy ship approaching the harbor, incinerating it before it could get any closer.

Some scholars have considered the possibility that the lighthouse also featured an ancient “fog horn” that would sound when the coast was shrouded by clouds. Arabic accounts describe “terrible voices” coming out of the building. The exact mechanism for an audio warning has not been identified. Some speculate that the tritons blowing conch shells along the uppermost tier of the lighthouse could have served a practical purpose as well as a decorative one.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024