Home | Category: Life and Culture in Prehistoric Europe

NEOLITHIC WEAPONS

According to Archaeology magazine: The use of a blunt object to strike an opponent may be the simplest — and the oldest — method of armed combat. A club known as the Thames Beater, was discovered in the mud on the banks of England’s Thames River and dates to around 3500 B.C. The beater was likely a utilitarian object employed in a variety of daily activities, as well as for self-protection. “Single-function weapons of violence are largely absent in the Neolithic period in Western Europe,” says archaeologist Linda Fibiger of the University of Edinburgh. “We tend to think of them as weapon-tools that probably had multiple functions, which could include use as a weapon.” [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

The polished, banded, perforated, 'mace-head' to the right was found near London, England and dates to c. 2,900 - 2,100 BC; mace-head has rectangular plan with rounded ends and an oval cross-section. There is an hour-glass perforation located approximately one third along its length. The carving of the mace-head has been worked so the natural banding of the stone forms transverse stripes. The mace is 14.8 centimeters in length and 5.8 centimeters wide; The diameter of perforation at widest point is two centimeters. It weighs about 0.6 kilograms The stone is tertiary metamorphic rock that may have originated in the Orkneys.

On the mace head to the right Jon Cotton writes: This is a splendid example of a mace-head of finely-banded olive-grey 'sandstone' with gently convex sides and a slightly obliquely-orientated hour-glass perforation drilled towards one end. The piece is otherwise symmetrical in plan and long-section.

Neolithic Europeans coveted hunting trophies just like modern hunters. In the remains of a prehistoric home in Croatia , alongside traces of wood furniture, researchers found a massive set of antlers — arm-length, with 14 points — that may have been hung on the wall as a trophy. They estimate the red deer buck would have weighed close to 500 pounds — a major prize for hunters armed only with stone weapons 6,500 years ago. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, November-December 2012]

RELATED ARTICLES:

STONE AGE AND BRONZE AGE VIOLENCE AND MASS MURDER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STONE AGE AND BRONZE AGE WARFARE factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING AND MEAT PROCESSING TECHNIQUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HUNTING BY HOMININS 500,000 TO 100,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

NEANDERTHAL HUNTING: METHODS, PREY AND DANGERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MEAT EATING BY LATE STONE AGE HUMANS factsanddetails.com

MEAT EATING BY HOMININS 500,000 to 80,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Arrowpoints, Spearheads, and Knives of Prehistoric Times” by Thomas Wilson (2022) Amazon.com

“Warfare in Neolithic Europe: An Archaeological and Anthropological Analysis” by Julian Heath (2017) Amazon.com;

“Practice and Prestige: An Exploration of Neolithic Warfare, Bell Beaker Archery, and Social Stratification from an Anthropological Perspective” by Jessica Ryan-despraz (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Shepherd Protects Their Flock: Looking at Warfare from the Neolithic to Sumerians” (2021) by Chris Flaherty Amazon.com;

“Emergent Warfare in Our Evolutionary Past” by Nam C Kim, Marc Kissel (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Warfare: Prehistories of Raiding and Conquest” by Elizabeth N. Arkush and Mark W. Allen (2008) Amazon.com;

“Warrior Scarlet” by Rosemary Sutcliff (1958) Novel Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution” by Susan Meyer (2016) Amazon.com;

“Constant Battles: The Myth of the Peaceful, Noble Savage” by Steven Le Blanc and Katherine E. Register (2003) Amazon.com;

“Warless Societies and the Origin of War” by Raymond C. Kelly (2000) Amazon.com;

“Massacres: Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology Approaches” by Cheryl P. Anderson and Debra L. Martin (2018) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in Human Evolution”

by John J. Shea (2016) Amazon.com;

“Flintknapping: Making and Understanding Stone Tools”

by John C. Whittaker (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Emergence of the Acheulean in East Africa and Beyond” by Rosalia Gallotti, Margherita Mussi Editors, (2018) Amazon.com;

” Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“Lithic Analysis (Manuals in Archaeological Method, Theory and Technique)”

by George H. Odell (2004) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Inventions” by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) Amazon.com

Early Bow and Arrows

Based on indirect evidence, the bow seems to have been invented near the transition from the Upper Paleolithic to the Mesolithic, some 10,000 years ago. The oldest direct evidence dates to 8,000 years ago. The discovery of stone points in Sibudu Cave, South Africa, has prompted the proposal that bow and arrow technology existed as early as 64,000 years ago.The oldest indication for archery in Europe comes from the Stellmoor in the Ahrensburg valley north of Hamburg, Germany and date from the late Paleolithic about 9000-8000 BC. The arrows were made of pine and consisted of a mainshaft and a 15-20 centimetre (6-8 inches) long foreshaft with a flint point. There are no known definite earlier bows or arrows, but stone points which may have been arrowheads were made in Africa by about 60,000 years ago. By 16,000 B.C. flint points were being bound by sinews to split shafts. Fletching was being practiced, with feathers glued and bound to shafts. [Source: Wikipedia]

5,000-year-old Iceman arrows The first actual bow fragments are the Stellmoor bows from northern Germany. They were dated to about 8,000 B.C. but were destroyed in Hamburg during the Second World War. They were destroyed before Carbon 14 dating was invented and their age was attributed by archaeological association.

The second oldest bow fragments are the elm Holmegaard bows from Denmark which were dated to 6,000 B.C. In the 1940s, two bows were found in the Holmegård swamp in Denmark. The Holmegaard bows are made of elm and have flat arms and a D-shaped midsection. The center section is biconvex. The complete bow is 1.50 m (5 ft) long. Bows of Holmegaard-type were in use until the Bronze Age; the convexity of the midsection has decreased with time. High performance wooden bows are currently made following the Holmegaard design.

Around 3,300 B.C. Otzi was shot and killed by an arrow shot through the lung near the present-day border between Austria and Italy. Among his preserved possessions were bone and flint tipped arrows and an unfinished yew longbow 1.82 m (72 in) tall. See Otzi, the Iceman

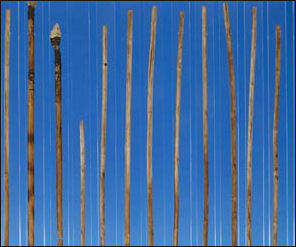

Mesolithic pointed shafts have been found in England, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. They were often rather long (up to 120 cm 4 ft) and made of European hazel (Corylus avellana), wayfaring tree (Viburnum lantana) and other small woody shoots. Some still have flint arrow-heads preserved; others have blunt wooden ends for hunting birds and small game. The ends show traces of fletching, which was fastened on with birch-tar. Bows and arrows have been present in Egyptian culture since its predynastic origins. The "Nine Bows" symbolize the various peoples that had been ruled over by the pharaoh since Egypt was united. In the Levant, artifacts which may be arrow-shaft straighteners are known from the Natufian culture, (10,800-8,300 B.C) onwards. Classical civilizations, notably the Persians, Parthians, Indians, Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese fielded large numbers of archers in their armies. Arrows were destructive against massed formations, and the use of archers often proved decisive. The Sanskrit term for archery, dhanurveda, came to refer to martial arts in general.

RELATED ARTICLE: EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING: BOWS, ARROWS AND ECOLOGY factsanddetails.com

Oldest Neolithic Bow Discovered in Europe

In 2012 researchers announced they had discovered the oldest Neolithic bow in Europe at La Draga Neolithic site in Banyoles. The complete bow measures 108 centimeters long and was constructed of yew wood. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona reported: “Archaeological research carried out at the Neolithic site of La Draga, near the lake of Banyoles, has yielded the discovery of an item which is unique to the western Mediterranean and Europe. The item is a bow dating from the period between 5400-5200 B.C., corresponding to the earliest period of settlement. It is the first bow to be found intact at the site. It can be considered the most ancient bow of the Neolithic period found in Europe.The bow is 108 centimeters long and presents a plano-convex section. It is made out of yew wood (Taxus baccata) as were the majority of Neolithic bows in Europe. [Source: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, June 29, 2012 ==]

“In previous archaeological digs, fragments of two bows were found (in 2002 and 2005) also from the same time period, but since they are fragmented it is impossible to analyze their characteristics in depth. The current discovery opens new perspectives in understanding how these farming communities lived and organized themselves. These bows could have served different purposes, such as hunting, although if one takes into account that this activity was not all that common in the La Draga area, it cannot be ruled out that the bows may have represented elements of prestige or been related to defensive or confrontational activities. Remains have been found of bows in Northern Europe (Denmark, Russia) dating from between the 8th and 9th centuries B.C. among hunter-gatherer groups, although these groups were from the Paleolithic period, and not the Neolithic. ==

“The majority of bows from the Neolithic period in Europe can be found in central and northern Europe. Some fragments of these Neolithic bows from central Europe date from the end of the 6th millennium B.C., between 5200-5000 B.C., although generally they are from later periods, often more than a thousand years newer than La Draga. For this reason archaeologists can affirm that the three bows found at La Draga are the most ancient bows in Europe from the Neolithic period. ==

“La Draga is located in the town of Banyoles, belonging to the county of Pla de l'Estany, and is an archaeological site corresponding to the location in which one of the first farming communities settled in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula. The site is located on the eastern part of the Banyoles Lake and dates back to 5400 and 5000 B.C.. The site occupies 8000 sq meters and stretches out 100 meters along the lake's shore and 80 meters towards the east. Part of the site is totally submerged in the lake, while other parts are located on solid ground. The first digs were conducted between the years 1990 and 2005, under the scientific leadership of the County Archaeological Museum of Banyoles. Since 1994, excavations were also carried out by the Centre for Underwater Research (Museum of Archaeology of Catalonia). The current project (2008-2013) includes participation by the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Spanish National Research Council. ==

“The site at La Draga is exceptional for several reasons. Firstly, due to its antiquity, which is considered to be one of the oldest of the Neolithic period existing in the Iberian Peninsula. Secondly, because it is an open-air site with a fairly continuous occupation. Lastly, and surely most remarkably, because of the exceptional conditions in which it is conserved. The archaeological levels are located in the phreatic layer surrounding Lake Banyoles, giving way to anaerobic conditions which favour the conservation of organic material. These circumstances make La Draga a unique site in all of the Iberian Peninsula, since it is the only one known to have these characteristics. In Europe, together with Dispilo in Greece and La Marmota in Italy, it is one of the few lake settlements from the 6th millennium B.C..” ==

weapon tips made from human bone from Doggerland

Doggerland Weapons Carved from Human Bone

About 11,000 years ago, Stone Age hunters in Doggerland crafted sharp weapons out of human bone, a new study finds. Doggerland refers to a vast area between present-day England and the Netherlands that was exposed when the ice sheets covering the land there melted around 18,000 years ago and was submerged by the sea about 12,000 years ago, when the level of the North Sea rose as more Ice Are glaciers melted. When it was above sea level Doggerland was inhabited by herds of animals and humans, whose remains and artifacts sometimes wash ashore in the Netherlands or are dredged up by fishing boats. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, December 24, 2020]

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science, An analysis of 10 Doggerland bone weapons revealed that eight were carved from red deer (Cervus elaphus) bone and antlers, and two were crafted from human bone. "We expected to find some deer, but humans? It wasn't even in my wildest dreams that there would be humans among them," study lead researcher Joannes Dekker, a Master's student of archaeology at Leiden University in the Netherlands, told Live Science.

It's a mystery why these weapons, known as barbed points, were carved from human bone. The research team couldn't think of a practical reason — human bones were likely hard to come by (unlike deer remains) and human bone isn't an especially great material for crafting sharp weapons — deer antler is much better, Dekker said. Rather, "there were probably cultural rules on what species to use for barbed point production," he said. "We think it was a conscious choice ... [that had to do] with the connotations and associations that people had with those [deceased] people as symbols."

The study on the Doggeland bones was published in the February 2021 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. Dekker noted his study was small, and only larger analyses may reveal how common human bone weapons were in Mesolithic Doggerland. It's also unclear which anatomical bone they came from, but one of the long leg or arm bones would have probably worked best, given the weapons' sizes, he said. One thing is clear: These bones were carved soon after the person's death, because fresh human bones are much easier to carve than dry, brittle ones, Dekker said. Although "the use of human bone for bone tools is so rare," it's not without precedent, Dekker said.New Guinea warriors, for instance, used daggers made from human thigh bones, but only from very important people.

Otzi, the Iceman's Weapons and Bow and Arrows

Otzi's ax

Otzi the Iceman is the name given to a 5,300-year-old mummified body of a man that was found in a glacier near the border of Italy and Austria. He is the best-preserved prehistoric man ever discovered with his own equipment and clothing. Among the items found with Iceman were his copper-blade ax, 14 arrows, a firestarter, a dagger with an ash handle and flint blade and a sheath, a half-finished yew-wood long bow (longer than a man is tall), a quiver filled with mostly half-finished arrows, an arrow repair kit, and pieces of antler used to make arrows. According to Archaeology magazine: The 14 arrows found in Ötzi’s doeskin quiver were made from branches of the wayfaring tree. Two of these arrows were ready to be fired, a trio of feathers still stuck to their ends with birch tar glue and nettle fibers. This design, with feathers arranged to produce a straight flight path, has remained virtually unchanged since. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

The copper ax was made from malachite — a copper carbonate that appears bluish-green on rock and cliff sides — that was scraped and flaked of the rock and smelted in a crucible over a campfire. The heat of the fire was increased by blowing oxygen through bellows. The nearly pure copper was then poured into a stone mold. This ax showed that people in Alpine possessed technology that was more sophisticated than previously thought. The fact that Otzi possessed such a fine weapon indicated that he was probably an elder in his village, and perhaps a leader.

Otzi’s hand slings and the design of his long, lightweight arrows indicate that he specialized in hunting ibex and mountain goats that live high above the tree line. Arrows of his design would not work well in the forest where they can get tangled up in brush. The feathers of the arrows indicate that people in Otzi’s time understood that the aerodynamic principal of a rotating arrow could be shot more accurately.

Otzi’s ash-handled flint dagger was probably used to cut leather and slice game. X-ray, CT scans and chemical analysis showed the unfinished bow was made of a yew tree cut lower down the mountain and arrows were tied to their shafts with sinew. Evidence shows also that Otzi retied his arrows, butchered animals with his flint knife and worked to reposition his copper ax head in its handle.

Otzi’s curved spike, edge sharpeners for his stone tools, and quiver were made from red deer skin or antler. Red deer bones were often fond in Neolithic sites. They were are common source of meat. Some scholars have speculated that Europe’s first forests were purposely cleared to create ideal conditions for hunting large red deer.

Composite Bow

4th century B.C.

Scythian archer The composite bow has been a formidable weapon for over 4,000 years. Described by the Sumerians in the third millennia B.C. and favored by steppe horsemen, the early versions of these weapons were made of slender strips of wood with elastic animal tendons glued to the outside and compressible animal horn glued on the inside. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Tendons are strongest when they are stretched, and bone and horn are strongest when compressed. Early glues were made from boiled cattle tendons and fish skin and were applied in very precise and controlled manner; and sometimes they took a year to dry properly.

Advanced bows that appeared centuries after the first composite bows appeared were made of pieces of wood laminated together and steamed into a curve, then bent into a circle opposite the direction it was going to be strung. Steamed animal horn was glued onto the "back," to make it hold its position. When the bow had "cured" a great amount of strength was required to bend it back to be strung. The finished product was nearly a hundred times stronger than a bow made from a sapling.

Long bows, used by medieval Europeans, employed the same principles of the composite bow but used heart and sap wood instead of tendons and horn. Long bows were just as powerful as composite bows but their large size and long arrows made them impractical to use from a horse. Both weapons could easily shoot an arrow over 300 years and piece armor at 100 yards. An advantage of the composite bow is that an archer could carry many more of the smaller arrows.

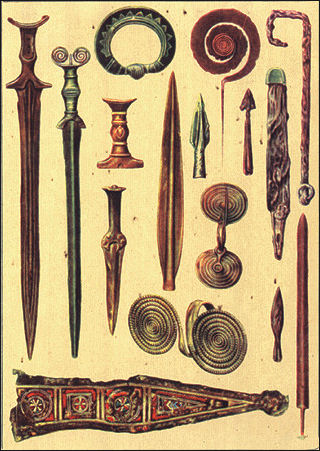

Copper Age and Bronze Age Weapons

Some natural copper contains tin. During the forth millennium in present-day Turkey, Iran and Thailand man learned that these metals could be melted and fashioned into a metal — bronze — that was stronger than copper, which had limited use in warfare because copper armor was easily penetrated and copper blades dulled quickly. Bronze shared these limitations to a lesser degree, a problem that was rectified until the utilization of iron which is stronger and keeps a sharp edge better than bronze, but has a much higher melting point. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

In Copper Age Middle East Period people living primarily in what is now southern Israel fashioned axes, adzes and mace heads, from coppers. In 1993, archaeologists found a skeleton of a Copper Age warrior in a cave near Jericho. The skeleton was found in a reed mat and linen ocher-died shroud (probably woven by several people with a ground loom) along with a wooden bowl, leather sandals, a long flint blade, a walking stick and a bow with tips shaped like a ram's horns. The warrior’s leg bone showed a healed fracture.

The Bronze Age lasted from about 4,000 B.C. to 1,200 B.C. During this period everything from weapons to agricultural tools to hairpins was made with bronze (a copper-tin alloy). Weapons and tools made from bronze replaced crude implements of stone, wood, bone, and copper. Bronze knives are considerable sharper than copper ones. Bronze is much stronger than copper. It is credited with making war as we know it today possible. Bronze sword, bronze shield and bronze armored chariots gave those who had it a military advantage over those who didn't have it.

Scientists believe, the heat required to melt copper and tin into bronze was created by fires in enclosed ovens outfitted with tubes that men blew into to stoke the fire. Before the metals were placed in the fire, they were crushed with stone pestles and then mixed with arsenic to lower the melting temperature. Bronze weapons were fashioned by pouring the molten mixture (approximately three parts copper and one part tin) into stone molds.

Bronze Age Dagger Made of Flint and Bark

Bronze Age weapons from RomaniaA Bronze Age dagger made of flint and bark and found in Rødbyhavn, Denmark was dated to 1700-500 B.C. and is 20 centimeters (7.8 inches) long. According to archaeology: Beginning in about 1700 B.C., a new material became available in northern Europe that would change the way entire classes of objects were made and how wealth and status were expressed. In Denmark, bronze, which was imported through extensive trade networks with southern Europe, became the material of choice for tools, weapons, ceremonial objects, and jewelry for more than a thousand years. But for the early years of the Bronze Age, when these networks were still developing, the toolmakers of Denmark were faced with a problem — not enough bronze. [Source: Archaeology magazine, January-February 2015]

Though scholars have long been aware of the shortage of raw materials, it wasn’t until fall 2014 that archaeologists from the Museum Lolland-Falster in southern Zealand discovered a unique artifact — a Bronze Age hafted dagger that wasn’t made of bronze. In fact, it was fashioned from flint. “We know this type of dagger existed,” says museum archaeologist Anders Rosendahl, “but to find an example is simply fantastic.” Although ordinarily an indispensable and valuable object such as a dagger would have been taken by its owner to his grave, the Rødbyhavn knife was found on an ancient seabed.

“The dagger is modeled after its bronze counterparts and demonstrates the skill that tool and weapon makers had developed during the preceding Neolithic period. The find is even more exciting, explains Rosendahl, because, in addition to the stone blade, the dagger’s shaft and even the birch bark wrapped around the handle to give the user a better grip were preserved after several thousand years.

Researchers Study Bronze Age Swords by Having Sword Fights with Copies

Bronze Age bronze swords much less strong and durable than their Iron Age iron counterparts. Bronze Age fighters developed combat styles and ways to use their less durable weapons, scientists have deduced, by engaging in mock combat using copies of real Bronze Age weapons. Their methodology and results were reported in a study in published in April 2020 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. “Unlike spears, arrows and axes, all of which have uses beyond combat, swords were “invented purely to kill someone,” Raphael Hermann, study lead author and an archaeologist at the University of Göttingen, told Science.[Source: Caroline Delbert, Popular Mechanics, April 25, 2020]

Caroline Delbert wrote in Popular Mechanics: “For a long time, archaeologists have assumed the countless bronze swords they’ve found were almost definitely for ceremonial use only. After all, bronze is super soft compared to almost any metal that came after in humankind’s development. To make accurate Bronze Age swords of different shapes and types, the researchers asked a “traditional bronzesmith” to make both a variety of swords and a variety of tools. Next, a traditional woodworker used those tools to craft sword handles, wooden shields, and other period-correct protective gear.

“The researchers then took cross sections of the weapons to make sure their interior composition matched what a Bronze Age process would produce. The team basically made microscope slides the same way other disciplines do, by mounting the object in a medium (epoxy resin, this time) and grinding the whole thing down to micro-thinness for examination.

“With the spirit of sportsmanship in mind, the research team recruited “members of a local club dedicated to medieval European combat,” Smithsonian reports, and had them act out choreographed swordplay using period-correct weapons made by a specialty blacksmith. By using these weapons in traditional ways, like a German method where opponents lock swords and almost wrestle rather than fight, the archaeologists ended up with patterns of nicks and wear that match up to the real antique weapons.

The scientists concluded: “The research has generated new understandings of prehistoric combat, including diagnostic and undiagnostic combat marks and how to interpret them; how to hold and use a Bronze Age sword; the degree of skill and training required for proficient combat; the realities of Bronze Age swordplay including the frequency of blade-on-blade contact; the body parts and areas targeted by prehistoric sword fencers; and the evolution of fighting styles in Britain and Italy from the late 2nd to the early 1st millennia B.C..”

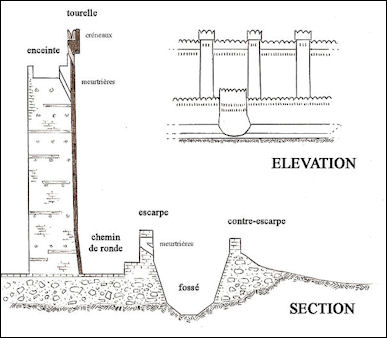

Early Defenses

Much is made about medieval castles as a defensive vehicle, but the technoloy they utilized — the moat, the fortress wall and observation towers — have been around since Jericho was established in 7000 BC. The ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians used siege devises — battering rams, scaling ladders, siege towers, mineshafts) between 2500 and 2000 BC. Some of the battering rams were mounted on wheels and had roofs to shield soldiers from arrows. The difference between siege towers and scaling ladders in that former resembled a protected staircase; mineshafts were built under walls to undermine their foundation and makes the wall collapse. There were also siege ramps and siege engines. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Fortress were usually made with the materials at the hand. The walled city of Catalhoyuk Hakat (7500 B.C). in Turkey and early Chinese fortresses were made of packed earth. The main purpose of a moat was not to stop attackers from climbing the wall but rather to keep them collapsing the base of the wall by mining underneath it.

Ancient Egyptian fort Pre-Biblical Jericho had an elaborate system of walls, towers and moats in 7,500 B.C. The circular wall that surrounded the settlement had a circumference of 700 feet and was10-feet-thick and 13-feet-high. The wall in turn was surrounded by 30-foot-wide, 10-foot-deep moat. Thirty-foot-high stone observation tower required thousands of man hours to build. The technology used to build them was virtually the same as those used in medieval castles. The original walls of Jericho appear to have been built for flood control rather defensive purposes. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The Greeks introduced catapults in the forth century BC. These primitive projectile throwers hurled stones and other object with torsion springs or counterweight (that operated a bit like a fat kid on one end of seesaw hurling another kid into the air). Catapults were generally ineffective as fortress breaking device because they were difficult to aim and didn't launch objects with much force. After gunpowder was introduced, cannons could blast walls in a particular place and the cannon balls traveled with a flat powerful trajectory.

Seizing a fortress was difficult. An army of hundreds inside a castle or strongholds could easily hold off thousands of attackers. The main assault strategy was to attack with a large number of men, hoping to spread the defenses thin and take advantage of a weak point. This strategy rarely worked and usually ended with a massive amount of casualties for the attackers. The most effective means of seizing a castle was bribing somebody on the inside to let you in, exploiting a forgotten latrine tunnel, making a surprise attack or setting up a position outside the castle and starving the defenders out. Most castles had huge stores of food (enough to last several hundred men at least a year) and often it was the attackers who ran out of food first.

Castles could be built relatively quickly. As time went on, fortification advances including the construction of inner and outer walls; towers outside the walls which gave defenders more positions to shoot from; maintain strongholds built outside the walls to defend vulnerable points like gates; elevated fighting platforms behind the walls which defenders could fire weapons from; battlements which were sort of like shields above walls. Advanced artillery fortifications of the 16th to 18th century had multi-level moats to trap attackers if they attempted to scale the walls, plus they were shaped like snowflakes or stars which gave the defenders all shorts of angles to shoot at their attackers.

World's Oldest Known Fort — Made 8,000 Years Ago by Hunter-Gatherers in Siberia

Hunter-gatherers built the oldest known fort about 8,000 years ago in Siberia, according to the study, published December 1, 2023 in the journal Antiquity, debunking the assumption that fortresses were associated with permanent agricultural settlements. These hunter-gatherers "defy conventional stereotypes that depict such societies as basic and nomadic, unveiling their capacity to construct intricate structures," study co-author Tanja Schreiber, an archaeologist at Free University of Berlin, told Live Science. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, December 20, 2023]

Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: Located along the Amnya River in western Siberia, remains of the Amnya fort include roughly 20 pit-house depressions scattered across the site, which is divided into two sections: Amnya I and Amnya II. Radiocarbon dating confirmed that the settlement was first inhabited during the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age, according to the study. When constructed, each pit house would have been protected by earthen walls and wooden palisades — two construction elements that suggest "advanced agricultural and defensive capabilities" by the inhabitants, the archaeologists said in a statement. "One of the Amnya fort's most astonishing aspects is the discovery that approximately 8,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers in the Siberian Taiga built intricate defense structures," Schreiber said. "This challenges traditional assumptions that monumental constructions were solely the work of agricultural communities."

It's unknown what triggered the need for these fortified structures in the first place, but the strategic location overlooking the river would have not only been an ideal lookout point for potential threats but also allowed hunter-gatherers to keep tabs on their fishing and hunting grounds, the researchers noted. "It remains uncertain whether these constructions were commissioned by those in authority or if the entire community collaborated in constructing them for the purpose of protecting people or valuables," Schreiber said. "Ethnohistorical records offer a nuanced comprehension of these forts, disclosing various potential reasons for fortifying residences."

Ancient forts were built for a number of reasons, according to these records, "such as securing possessions or individuals, handling armed conflicts, addressing imbalances in attacker-defender ratios, thwarting raids and functioning as elaborate signals by influential chiefs," Schreiber said.

Mysterious 3,000-Year-Old ‘Semi-Buried Boulders’ in Italy — Part of a Fort

About 50 years ago, archaeologists using aerial photography to investigate the ruins of a 3,000-year-old island village on the Italian island of Ustica, north of Sicily, were perplexed by the presence of peculiar “semi-buried boulders” on the outskirts of the settlement. They couldn’t figure out why the boulders were there. A study published in the January 2024 issue of the Journal of Applied Geophysics provided an explanation: the boulders were once part of a “complex” fortification system, serving as a first layer of defense for the already enclosed village, according to [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, January 6, 2024]

The remnants of the wall were discovered outside the village of Faraglioni, which was established on the volcanic island of Ustica around 1400 B.C., archaeologists said. The village was mysteriously abandoned around 1200 B.C. Experts consider the site one of the best-preserved Mediterranean settlements of the Bronze Age, according to a January 5, 2024 release from the Austria Press Agency. The village had a sophisticated urban layout, with dozens of huts lining narrow streets.

The village was positioned on the edge of a cliff, so one side was naturally protected by the cliffside and ocean. The inland edge of the village was guarded by a “massive fortified wall” that is still standing, archaeologists said. Researchers said the “mighty curved” wall is about 820 feet long and 13 feet tall. It resembles a “fish hook” and connects to the huts through a passage.

The peculiar boulders were found about 20 feet from the standing inner wall, “discontinuously” following the same structure and shape of the inner wall, the study said. Archaeologists also discovered the remains of a tower between the standing wall and the boulders that appears to be connected to both structures. Using photographs and various survey methods, it was determined that the boulders were actually remnants of an exterior wall that likely served as a first defense for the huge Bronze Age settlement, according to experts.

“The defensive system of the Faraglioni Middle Bronze Age village at Ustica consisted of two main elements: a large peripheral outwork, and an internal wall reinforced by buttresses, both having an arched design and mutually distant (19 to 22 feet),” archaeologists said. “Their construction was aimed at isolating the marine terrace and the village from the Tramontana plain.” Archaeologists said the defense system’s purpose was likely two-fold: It defended the village while also establishing the settlement’s borders and creating a social structure.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Otzi Museum, Doggerland from Dekker J, et al. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, National Museum of Antiquities Leiden

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books) and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024