Home | Category: First Modern Human Life / Life and Culture in Prehistoric Europe

EARLY MODERN HUMAN LANGUAGE

It is not known when language first emerged. According to some theories it emerged around 50,000 years and developed hand in hand with the development of behavioral modern human beings. Some believe this happened when some genetic change occurred allowing one group to develop speech and this group advanced, dominated other groups and multiplied.

Gregory D.S. Anderson, director of the Living Tongues Institute, told the Washington Post, “In the pre-agricultural state, the norm was to have lots and lots of little languages. As humans developed with agriculture, larger population groups were able to aggregate together, and you get large languages developing."

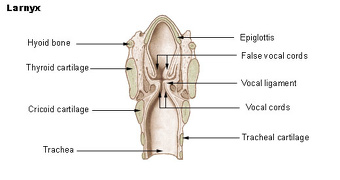

Scientists believe that Neanderthals may have had a spoken language based on the fact that they had hyoid bones---which hold up the voice box in modern humans---virtually identical to those in modern humans and a hypoglossal canal---a bony canal in the occipital bone of the skull theorized role to have a role in speech;. Christopher Stringer of the Natural History Museum of London told National Geographic, "They may not have had language as complex as ours. We have symbolism. They may not have all had all that, but at least they could talk to each other." Some scientists dismiss the presence of the hypoglossal canal as evidence of speech, pointing out that monkeys and apes have the same size canal. Neanderthals posses the same version of the gene FOXP2, which has been linked it speech and language, as humans.

The development of language appears to have a genetic component. A strong can be made that gene called FOXP2 is involved human language. When a certain mutation occurs to the gene humans lose their ability to make sense of language and produce coherent speech. The gene occurs across the animal kingdom, When FOXP2 is disrupted in birds, their songs are messed upped. With bats, it affects echolocation. How the gene affects language is not known. The amino acid sequence between humans and chimpanzees is the same, except in two of the 715 sequences, with a mutation possibly the key behind why humans have spoken language and chimps don’t

See Separate Article: EVOLUTION OF LANGUAGE IN OUR HUMAN ANCESTORS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“On the Origins of Human Speech and Language”

By George Poulos Amazon.com;

“The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World's Oldest Symbols”

by Genevieve von Petzinger Amazon.com

“The Evolution of Human Consciousness and Linguistic Behavior: A Synthetic Approach to the Anthropology and Archaeology of Language Origins” by Karen A. Haworth and Terry J. Prewitt Amazon.com

How Language Began: The Story of Humanity's Greatest Invention

by Daniel L. Everett (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour of Mankind's Greatest Invention”

by Guy Deutscher (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Social Conquest of Earth” by Edward O. Wilson (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Paleolithic Revolution (The First Humans and Early Civilizations)” by Paula Johanson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Paleolithic Technologies (Routledge Studies in Archaeology)”

by Steven L. Kuhn Amazon.com;

“Numbers and the Making of Us: Counting and the Course of Human Cultures” by Caleb Everett Amazon.com

Modern Remnants of a 15,000-Year-Old Language

David Brown wrote in the Washington Post: “You, hear me! Give this fire to that old man. Pull the black worm off the bark and give it to the mother. And no spitting in the ashes!’ It’s an odd little speech. But if you went back 15,000 years and spoke these words to hunter-gatherers in Asia in any one of hundreds of modern languages, there is a chance they would understand at least some of what you were saying. That’s because all of the nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs in the four sentences are words that have descended largely unchanged from a language that died out as the glaciers retreated at the end of the last Ice Age. Those few words mean the same thing, and sound almost the same, as they did then.[Source: David Brown, Washington Post, May 6, 2013 +]

“The traditional view is that words can’t survive for more than 8,000 to 9,000 years. Evolution, linguistic “weathering” and the adoption of replacements from other languages eventually drive ancient words to extinction, just like the dinosaurs of the Jurassic era. A new study, however, suggests that’s not always true. A team of researchers has come up with a list of two dozen “ultraconserved words” that have survived 150 centuries. It includes some predictable entries: “mother,” “not,” “what,” “to hear” and “man.” It also contains surprises: “to flow,” “ashes” and “worm.” +

“Mark Pagel, an evolutionary theorist at the University of Reading in England and three collaborators studied “cognates,” which are words that have the same meaning and a similar sound in different languages. Father (English), padre (Italian), pere (French), pater (Latin) and pitar (Sanskrit) are cognates. Those words, however, are from languages in one family, the Indo-European. The researchers looked much further afield, examining seven language families in all.” +

“Proto-Eurasiatic” Language

David Brown wrote in the Washington Post: “The existence of the long-lived words suggests there was a “proto-Eurasiatic” language that was the common ancestor to about 700 contemporary languages that are the native tongues of more than half the world’s people. “We’ve never heard this language, and it’s not written down anywhere,” said Pagel who headed the study published in May 2013 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “But this ancestral language was spoken and heard. People sitting around campfires used it to talk to each other.” [Source: David Brown, Washington Post, May 6, 2013 +]

“In all, “proto-Eurasiatic” gave birth to seven language families. Several of the world’s important language families, however, fall outside that lineage, such as the one that includes Chinese and Tibetan; several African language families, and those of American Indians and Australian aborigines. That a spoken sound carrying a specific meaning could remain unchanged over 15,000 years is a controversial idea for most historical linguists. +

““Their general view is pessimistic,” said William Croft, a professor of linguistics at the University of New Mexico who studies the evolution of language and was not involved in the study. “They basically think there’s too little evidence to even propose a family like Eurasiatic.” In Croft’s view, however, the new study supports the plausibility of an ancestral language whose audible relics cross tongues today. +

“In addition to Indo-European, the language families included Altaic (whose modern members include Turkish, Uzbek and Mongolian); Chukchi-Kamchatkan (languages of far northeastern Siberia); Dravidian (languages of south India); Inuit-Yupik (Arctic languages); Kartvelian (Georgian and three related languages) and Uralic (Finnish, Hungarian and a few others). They make up a diverse group. Some don’t use the Roman alphabet. Some had no written form until modern times. They sound different to the untrained ear. Their speakers live thousands of miles apart. In short, they seem unlikely candidates to share cognates.” +

Indo-European languages

Starting with 200 Words That Are Core Vocabulary of All Languages

David Brown wrote in the Washington Post: “Pagel’s team used as its starting material 200 words that linguists know to be the core vocabulary of all languages. Other researchers had searched for cognates of those words in members of each of the seven Eurasiatic language families. They looked, for example, for similar-sounding words for “fish” or “to drink” in the Altaic family of languages or in the Indo-European languages. When they found cognates, they constructed what they imagined were the cognates’ ancestral words — a task that requires knowing how sounds change between languages, such as “f” in Germanic languages becoming “p” in Romance languages. [Source: David Brown, Washington Post, May 6, 2013 +] “Those made-up words are called “proto-words.” Pagel’s team compared them among language families. They made thousands of comparisons, asking such questions as: Do the proto-word for “hand” in the Inuit-Yupik language family and the proto-word for “hand” in the Indo-European language family sound similar? +

“Surprisingly, the answer to that question and many others was yes. The 23 entries on the list of ultraconserved words are cognates in four or more language families. Could they sound the same purely by chance? Pagel and his colleagues think not. Linguists have calculated the rate at which words are replaced in a language. Common ones disappear the slowest. It’s those words that Pagel’s team found were most likely to have cognates among the seven families. In fact, they calculated that words uttered at least 16 times per day by an average speaker had the greatest chance of being cognates in at least three language families. If chance had been the explanation, some rarely used words would have ended up on the list. But they didn’t. +

“As a group, the ultraconserved words give a hint of what has been important to people over the millennia. “I was really delighted to see ‘to give’ there,” Pagel said. “Human society is characterized by a degree of cooperation and reciprocity that you simply don’t see in any other animal. Verbs tend to change fairly quickly, but that one hasn’t.” +

“Of course, one has to explain the presence of “bark.” “I have spoken to some anthropologists about that, and they say that bark played a very significant role in the lives of forest-dwelling hunter-gatherers,” Pagel said. Bark was woven into baskets, stripped and braided into rope, burned as fuel, stuffed in empty spaces for insulation and consumed as medicine.“To spit” is also a surprising survivor. It may be that the sound of that word is just so expressive of the sound of the activity — what linguists call “onomatopoeia” — that it simply couldn’t be improved on over 15,000 years. As to the origin of the sound of the other ultraconserved words, and who made them up, that’s a question best left to the poets.

Are the “F” and “V” Sounds the Result of Agriculture

Lydia Pyne wrote in Archaeology magazine: Try saying “f” and “v” and pay close attention to your lower lip and upper teeth. Would it surprise you to learn that these sounds are relatively recent additions to human languages? Languages, of course, develop over time as usage, meaning, and pronunciation change. But what about the ways our bodies have changed over the millennia? Could this also contribute to changes in language? In a new study, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of Zurich have used evidence from paleoanthropology, speech biomechanics, ethnography, and historical linguistics to determine that, in fact, it is a combination of factors — both cultural and biological — that produces changes in language and has contributed to the diversity of languages that exist today. [Source: Lydia Pyne, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2019]

Indo-European languages

“In the Neolithic period, starting about 10,000 years ago, when the lifestyle of people in Europe and Asia changed dramatically as a result of the large-scale adoption of farming in place of hunting and gathering, their biology changed, too. Prior to this shift, the consumption of gritty, fibrous foods such as nuts and seeds, staples of the pre- Neolithic diet, put a great deal of force on children’s growing mandibles and wore down their molars. In response to the biomechanical stress of chewing these tough foods, people’s jawbones grew larger and larger over their lifetimes, and their molars drifted toward the front of the mouth, eliminating their childhood overbites. With the development of farming, easily chewable foods such as processed dairy products and milled grains were introduced into people’s diets. As the prevalence of these foods increased, people began to retain their childhood overbites well into adulthood.

“What humans eat has had profound impacts on our biological and cultural history for thousands of years, and will certainly continue to do so. “I think the results from this study show that when it comes to the debate of ‘Are humans still evolving?’ the answer is clearly yes,” says archaeologist Suzanne Pilaar Birch of the University of Georgia. “[Language] is yet another relatively recent example that corresponds to the deep and multifaceted influences of the development of an agricultural lifestyle on humanity. We are only just beginning to understand how complex and intertwined these sociobiological impacts are.”

Research That Linked the “F” and “V” Sounds to Agriculture

Lydia Pyne wrote in Archaeology magazine: “In the 1980s, a linguist named Charles Hockett proposed that this physical change helped lead to a change in the sorts of sounds included in languages, but his theory gained little traction. The current team, led by linguists Damián Blasi and Steven Moran, set out to test Hockett’s theory. They anticipated finding that he had been incorrect. The team used computer models of jaws and teeth exhibiting different bite patterns to investigate the linguistic consequences of the move to a diet of softer foods. Specifically, they wanted to test the implications of an extended overbite against the pre-Neolithic edge-to-edge bite. “I think that we largely use this idealized notion of humans as coming with a fixed, uniform biological profile, which is a reasonable starting point,” Blasi says. “But the copious evidence for human adaptation at the biological level to different diets, behaviors, and ecologies needs to be considered more seriously if we want to have an integral view of the factors shaping the structure of languages.” [Source: Lydia Pyne, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2019]

“Blasi, Moran, and their team demonstrated, to their surprise, that how a person’s teeth align can lead to significant differences in the sounds they tend to make. Most importantly for their study, they showed that people with retained overbites could more easily articulate a range of consonants called labiodentals — produced when the lower lip comes into contact with the upper teeth. Examples of labiodentals include “f” and “v.” An overbite, they found, enables people to make these sounds with 29 percent less muscular effort than doing so with an edge-to-edge bite. At the same time, an overbite makes it harder to produce bilabials, such as “b” and “p,” which require the lips to be pressed together. As a result, these sounds frequently morphed into labiodentals. The addition of the labiodentals contributed, in turn, to the proliferation of languages after the Neolithic, so much so that thousands of years later, these speech sounds are present in 76 percent of the several hundred extant languages of the Indo- European family. These include most of the languages of modern Europe, as well as many of Asia.

“The researchers then examined modern languages and found that hunter-gatherer languages, such as those found in parts of northwestern Australia, Greenland, and southern Africa, use only one-fourth as many labiodentals as the languages of agricultural or farming societies. “Our new research suggests that a biological perspective is indeed necessary to resolve why languages have the range of sounds they have,” says Moran. Taken together, these lines of evidence paint a compelling picture of language diversification being tied to diet.

Eurastic Language Tree

Indo-European Languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family that originated in western and southern Eurasia. It includes most of the languages of Europe as well as ones from northern Indian subcontinent and the Iranian English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Danish, Dutch, Spanish, Hindi, Farsi, Greek, Italian are all Indo-Europe languages. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic. An additional six subdivisions are now extinct. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Indo-European family of language includes most languages spoken from Ireland to Russia to the northern half of India. Around 46 percent of the world's population (3.2 billion people) speaks an Indo-European language as a first language, far and away the largest of any language family. According to Ethnologue, there are about 445 Indo-European languages still spoken today, with over two-thirds of them in the Indo-Iranian branch. The most widely-spoken individual Indo-European languages are English, Hindustani, Spanish, Bengali, French, Russian, Portuguese, German, Persian and Punjabi, each with over 100 million speakers. Among the Indo-European languages that are small and in danger of extinction are Cornish, which has fewer than 600 speakers.

All Indo-European languages are descended from a single prehistoric language, reconstructed as Proto-Indo-European (PIE), spoken sometime in the Neolithic to early Bronze age. The Indo-European family is not known to be linked to any other language family through any more distant genetic relationship, although several disputed proposals to that effect have been made

See Separate Article: INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except blue-eyed black girl, Afritorial

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024