Home | Category: Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe / Bronze Age Europe / Life and Culture in Prehistoric Europe

11,000-YEAR-OLD REINDEER HUNTING STRUCTURE FOUND IN THE BALTIC SEA

Ashley Strickland of CNN wrote: Researchers and students from Kiel University in Germany first came across the surprising row of stones located about 69 feet (21 meters) underwater during a marine geophysical survey along the seafloor of the Bay of Mecklenburg, about 6 miles (9.7 kilometers) off the coast of Rerik, Germany. The discovery, made in the fall of 2021 while aboard the research vessel RV Alkor, revealed a wall made of 1,670 stones that stretched for more than half a mile (1 kilometer). The stones, which connected several large boulders, were almost perfectly aligned, making it seem unlikely that nature had shaped the structure. A study describing the structure was published in February 2024 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.[Source: Ashley Strickland, CNN, February 13, 2024]

The team determined that the wall was likely built by Stone Age communities to hunt reindeer more than 10,000 years ago. “Our investigations indicate that a natural origin of the underwater stonewall as well as a construction in modern times, for instance in connection with submarine cable laying or stone harvesting are not very likely. The methodical arrangement of the many small stones that connect the large, non-moveable boulders, speaks against this,” said lead study author Dr. Jacob Geersen, senior scientist at the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research in Germany, in a statement.

The wall was likely built along the shoreline of a lake or a bog, according to the study. Rocks were plentiful in the area at the time, left behind by glaciers that had moved across the landscape. But studying and dating submerged structures is incredibly difficult, so the research team had to analyze how the region has evolved to determine the approximate age of the wall. They collected sediment samples, created a 3D model of the wall and virtually reconstructed the landscape where it was originally built.

Sea levels rose significantly after the end of the last ice age about 8,500 years ago, which would have led to the wall and large parts of the landscape being flooded, according to the study authors. “At this time, the entire population across northern Europe was likely below 5,000 people. One of their main food sources were herds of reindeer, which migrated seasonally through the sparsely vegetated post-glacial landscape,” said study coauthor Dr. Marcel Bradtmöller, research assistant in prehistory and early history at the University of Rostock in Germany, in a statement. “The wall was probably used to guide the reindeer into a bottleneck between the adjacent lakeshore and the wall, or even into the lake, where the Stone Age hunters could kill them more easily with their weapons.” The hunter-gatherers used spears, bows and arrows to catch their prey, Bradtmöller said.

A secondary structure may have been used to create the bottleneck, but the research team hasn’t found any evidence of it yet, Geersen said. However, it’s likely that the hunters guided the reindeer into the lake because the animals were slow swimmers, he said. And the hunter-gatherer community seemed to recognize that the deer would follow the path created by the wall, the researchers said. “It seems that the animals are attracted by such linear structures and that they would rather follow the structure instead of trying to cross it, even if it is only 0.5 meters (1.6 feet) high,” Geersen said.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Early Neolithic of Northern Europe: New Approaches to Migration, Movement and Social Connection” by Daniela Hofmann, Vicki Cummings, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“An Ethnography of the Neolithic: Early Prehistoric Societies in Southern Scandinavia” by Christopher Tilley (1996) Amazon.com;

“Woodland in the Neolithic of Northern Europe: The Forest as Ancestor” by Gordon Noble (2017) Amazon.com;

“Paths Towards a New World: Neolithic Sweden” by Mats Larsson and Geoffrey Lemdahl (2014) Amazon.com;

“Monuments in the Making: Raising the Great Dolmens in Early Neolithic Northern Europe” by Vicki Cummings and Colin Richards (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings” by Jean Manco (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic: Relations and Descent” by Alasdair Whittle, Joshua Pollard (2023) Amazon.com;

“Seeking the First Farmers in Western Sjælland, Denmark: The Archaeology of the Transition to Agriculture in Northern Europe” by T. Douglas Price (2022) Amazon.com;

“Foragers and Farmers: Population Interaction and Agricultural Expansion in Prehistoric Europe” by Susan A. Gregg (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Transition and the Genetics of Populations in Europe (Princeton Legacy Library)” by Albert J. Ammerman and L L Cavalli-sforza (2016) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe” by Chris Fowler, Jan Harding, Daniela Hofmann (2015) Amazon.com;

“Northern Archaeology and Cosmology: A Relational View” by Vesa-Pekka Herva, Antti Lahelma Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Shamanism: Spirit Work in the Norse Tradition” by Raven Kaldera (2012) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Northern Europe” by H.R. Ellis Davidson (1965) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Rock Art in Scandinavia: Agency and Environmental Change” by Courtney Nimura (2015) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age Rock Art in Iberia and Scandinavia: Words, Warriors, and Long-distance Metal Trade” by Johan Ling, Marta Díaz-Guardamino, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“In the Darkest of Days: Exploring Human Sacrifice and Value in Southern Scandinavian Prehistory” by Matthew J. Walsh , Sean O'Neill, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Seaways to Complexity: A Study of Sociopolitical Organisation Along the Coast of Northwestern Scandinavia in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age” by Austvoll and Knut Ivar (2020) Amazon.com;

“Organizing Bronze Age Societies: The Mediterranean, Central Europe, and Scandanavia Compared” by Timothy Earle, Kristian Kristiansen Amazon.com;

“European Societies in the Bronze Age” by A. F. Harding (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age” by Anthony Harding and Harry Fokkens (2020) Amazon.com;

Reindeer Hunters in Norway Used Arrows with Quartzite Tips 4,000 Years Ago

In September 2023, archaeologists said they had discovered a "very rare" ancient arrow that still has its quartzite arrowhead and feather fletching in place.in Norway's mountains have It's likely that reindeer hunters used the weapon up to 4,000 years ago, archaeologist Lars Pilø, who heads the Secrets of the Ice project in the Jotunheimen Mountains of central Norway's Oppland region, said. Archaeologists with the project had previously found human-made hunting blinds used by reindeer hunters. "There are no hunting blinds in the immediate vicinity, but this arrow was found along the upper edge of the ice, so the hunters may simply have been hiding behind the upper ridge," Pilø told Live Science. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, September 28, 2023]

Live Science reported: Secrets of the Ice glacial archaeologist Espen Finstad discovered the arrow on September 13, 2023. Due to human-caused climate change, the snow and ice in the Jotunheimen Mountains is melting, exposing artifacts from hundreds to thousands of years ago. If archaeologists don't find these human-made items quickly after being exposed, the artifacts can deteriorate in the elements.Finstad found the arrow during a targeted survey, when he and colleagues "checked newly exposed areas along the edge of the ice," Pilø said.

An analysis revealed that the arrow's shaft was made of birch and that it still had an aerodynamic fletching with three preserved feathers. Hunters use fletching to help guide the arrow in flight, but these typically decay over time. The quartzite arrowhead at the front of the shaft "is barely visible because pitch covers most of the arrowhead," Pilø said. "The pitch was used for securing the arrowhead to the shaft and to smooth the front of the arrow, allowing for better penetration. Arrows with preserved arrowheads still attached are not uncommon during the Iron Age on our ice sites, but this early they are very rare." The pitch likely came from birch charcoal, he added. Despite its well-preserved arrowhead and feathers, the rest of the arrow fared slightly worse. The roughly 2.9-foot-long (90 centimeters) arrow broke into three pieces along its shaft, "probably due to snow pressure," Pilø said.

Pilø told Business Insider the arrow likely ended up in the ice while hunters were pursuing reindeer, which gathered near ice and snow on hot days to avoid botflies. "The ancient hunters knew this and would have hunted the reindeer en route to and on the ice patch," said Pilø. "Sometimes, when an arrow missed its target, it burrowed itself deep into the snow and was lost. Sad for the hunter but a bull's eye for archaeology!" [Source: Sebastian Cahill, Business Insider, September 9, 2023]

Earliest Evidence of Fermentation — 9000-Year-Old Fish — Found in Sweden

In 2016, osteologists studying a 9,200-year-old lakeside site in Sweden said they found the earliest known example of fermentation — an important method of food preservation and a way to make wine and beer — in a large storage area.. Archaeology reported: Below an area thick with fish bones they found a 10-foot-long pit surrounded by postholes. Evidence led them to conclude that these early Mesolithic people were fermenting fish 1,500 years before fermentation was used anywhere else in the world — to make wine. The finding also suggests people may have formed settlements here 3,000 years earlier than previously thought. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

large-scale storage for fermented fish dating back to 7,200 BC; here is the gutter after 50 percent of it had been removed; notice the stark contrast with the surrounding clay under the gutter as well as between the stakeholes and the surrounding clay

A team led by Dr. Boethius of Lund University found roughly 200,000 fish bones at Norje Sunnansund, an Early Mesolithic settlement site in the Blekinge province in southeast Sweden, dated to around 9,600 – 8,600 years ago on the shores of the ancient Lake Vesan, next to a two- kilometer long outlet leading to the Baltic basin. Dr. Boethius said, “We’d never seen a site like this with so many well preserved fish bones, so it was amazing to find,” he added. [Source: Enrico de Lazaro, sci-news.com, February 9, 2016]

The archaeologists also uncovered a long pit surrounded by small stake holes and completely filled with fish bones. “It was really strange, and because of all the fish bones in the area we knew something was going on even before we found the feature,” Dr. Boethius said. “At first we had no idea what it was so we rescued it from the area to investigate.”

According to sci-news.org “He analyzed the feature and the contents and discovered the fish bones were from freshwater fish such as cyprinids (the carps, the true minnows, and their relatives), the European perch (Perca fluviatilis), the northern pike (Esox lucius), the ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernua), the European eel (Anguilla anguilla), the burbot (Lota lota) and other species.

He also showed the fish had been fermented — a skillful way of preserving food without using salt. “The fermentation process is also quite complex in itself,” said Dr. Boethius, who is an author of a paper published online February 6 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

“Because people did not have access to salt or the ability to make ceramic containers, they acidified the fish using, for example, pine bark and seal fat, and then wrapped the entire content in seal and wild boar skins and buried it in a pit covered with muddy soil. This type of fermentation requires a cold climate.”

“The discovery is unique as a find like this has never been made before,” he added. “That is partly because fish bones are so fragile and disappear more easily than, for example, bones of land animals. In this case, the conditions were quite favorable, which helped preserve the remains.”

“The amount of fish we found could have supported a large community of people,” the archaeologist said. The findings are important as it is usually argued that people in the north lived relatively mobile lives, while people in the Levant became settled and began to farm and raise cattle much earlier. “These findings suggest that people who survived by foraging for food were actually more advanced than assumed,” Dr. Boethius said.

7,000-Year-Old Fish Traps Used in a Norway Lake

In the summer of 2022, Reidar Marstein, a hiker and amateur archaeologist, was admiring the view on the bank of a lake in Norway. He glanced down and laid eyes a series of wooden poles plunged into the dry . The poles turned out to be part of a 7,000-year-old fishing trap.according to a September 2022 news release from the Cultural History Museum. The a receding shoreline exposed the trap. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, June 23, 2023]

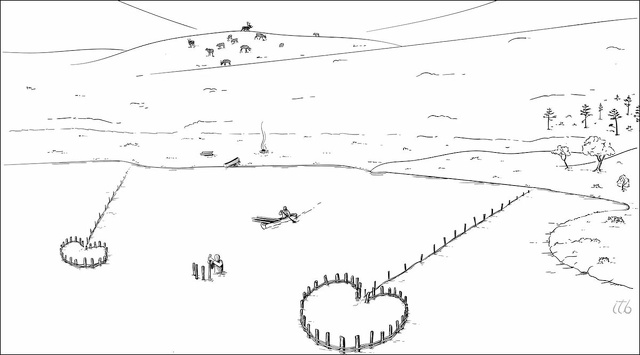

Archaeologists dated the trap’s wooden logs to 5000 B.C., making them the oldest fish traps in Norway and the oldest trap of their kind in northern Europe. Aspen Pflughoeft wrote in the Miami Herald: The fish traps were made of sharpened wooden poles plunged into the lakebed. The traps sat in shallow water and likely had a lollipop-like shape, according to the release. Fish were funneled along a wooden fence and into the main circular trap chamber. Once inside, ancient fishermen could haul in their catch from a boat or by wading into the cold water, the release said. An illustration shows what the traps probably looked like. But the lake’s rising water levels submerged the Stone Age traps before archaeologists could excavate last summer. Water levels in Tesse lake, about 180 miles northwest of Oslo, fluctuate seasonally, the Cultural History Museum said. The lake shrinks in the early summer when it’s drained to produce power and refills as summer weather melts the surrounding snow.

Archaeologists located four fish traps and fully excavated one, the museum said in a June 21, 2023 update. They unearthed more than 50 incredibly well preserved wooden poles. The poles were chopped, sharpened and plunged deep into the lakebed, “The poles are pointed at the end and were clearly driven into the seabed with quite a bit of force,” Axel Mjærum, the archaeologist managing the excavation, told Science in Norway. “The pointed ends are slightly damaged at the tip.”

Excavations also uncovered materials that sat between the poles, made the chamber of the trap tight and prevented fish from escaping, the museum said. The ancient hunters who built and used these fish traps likely followed reindeer into the mountains, the release said. “Fishing is safe and predictable,” Mjærum told Science in Norway. “Hunting reindeer with a bow and arrow is perhaps more prestigious, but also more unpredictable. It is not the fish that have drawn these people to the mountains… but the fish have made it possible to engage in reindeer hunting, which we know has been important to them.” Previous excavations around Tesse lake had uncovered ruins of Stone Age settlements, Science in Norway reported.

Did Norwegians Hunt Bluefin Tuna and Whales with Bone Harpoons 5,000 Years Ago?

In the 1930s, a farmer at Jortveit farm in southern Norway found bones from a bluefin tuna and a killer whale along with huge fish hooks and harpoons made of bones in the middle an inland wetland that were dated between 3700 and 2500 years B.C.. The tools ended up in the University Museum of Antiquities in Oslo, where they were studied by archaeologists, and bones were examined by geologists at the Natural History Museum. In the 2010s, Svein Vatsvåg Nielsen, a PhD candidate from the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History, decided to take a closer look. [Source: Ingrid Spilde, Science Norway, June 26, 2020]

Five thousand years the sea was higher than today in Scandinavia, and the area where the farmer’s wetland field is located was probably a lagoon. At around 125 centimeters below the surface, Nielsen found piles of mostly bluefin tuna bones and reported his findings in the Journal of Wetland Archaeology, which included arrowheads, fish hooks and harpoons. But mostly bones. Some of the bones are from cod or small whales, but they are mainly from bluefin tuna — a large fish.

Together, the bones and the implements tell a story, Nielsen told Science Norway. People from nearby settlements fished in the lagoon. Occasionally, bluefin tuna followed schools of herring or mackerel into the lagoon. Then people were probably able to hunt them from boats. All the bones at the bottom may be due to the fact that the fishermen cleaned the fish before they went ashore. Or they may be the remains of fish that escaped but were too injured to survive. “It’s unlikely that so many bluefin tuna just ended up there by chance,” says Nielsen. If some natural phenomenon had killed the fish in the lagoon, there would be bones from many different species there, not just from bluefin tuna.

The harpoons from the wetland are also very similar to harpoons that archaeologists know were used solely to catch big fish or small whales. “There could have been people out in boats hundreds of times a year. And there are signs that there has been activity on the site over a period of a thousand years,” he says. “It’s a risky endeavour to catch a bluefin with harpoon from a boat,” says Nielsen. The fish are very strong. If the foot of an unlucky fisherman got stuck in the fishing line, it is not unlikely that his story would have ended at a depth of nine meters.

7,000-Year-Old Woman — One Sweden's Last Hunter-Gatherers

Kristin Romey wrote in National Geographic: To the archaeologist who excavated her remains, she’s Burial XXII. To the staff at Sweden’s Trelleborg Museum she’s known as the “Seated Woman”. The woman was buried upright, seated cross-legged on a bed of antlers. A belt fashioned from more than 100 animal teeth — including those of deer, wild boar, and moose — hung from her waist and a large slate pendant from her neck. A short cape fashioned from crow, magpie, gull, jay, goose, and duck feathers covered her shoulders. [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, November 12, 2019]

From her bones, archaeologists were able to determine that she stood a bit under five feet tall and was between 30 and 40 years old when she died. DNA extracted from other individuals in the burial ground where she was found confirmed what we know about Mesolithic peoples in Europe — that they were dark skinned and pale eyed.

Lars Larsson recalls excavating Burial XXII at the archaeological site of Skateholm, near Trelleborg, in the early 1980s. It was one of more than 80 ancient graves recorded at Skateholm, which ranged in dates from roughly 5,500 to 4,600 B.C. and included a variety of burial types, including people interred in pairs or with dogs, and individual dogs buried with rich grave offerings. Burial XXII was one of only a handful of seated interments, however, and archaeologists decided to excavate the burial as a single block that would to be transported to a lab for further investigation.

5,200-Year-Old Vittrup Man — the Scandinavian Vagabond

About 5,200 years ago, a bog man known as “Vittrup Man,” the oldest known immigrant in Denmark’s history, ended his life violently in a peat bog in Vittrup in northwest Denmark. In 1915, hiis right anklebone, lower left shinbone, jawbone and fragmented skull were found alongside a wooden club by peat cutters. Researchers estimate that he died after being hit over the head at least eight times with the wooden club sometime between 3100 B.C. and 3300 B.C.. Scientists analyzed Vittrup Man’s remains as part of a study published in Nature about Denmark’s genetic prehistory in which the genomes of 317 ancient skeletons were sequenced. Some of the same researchers decided to conduct an individual study of Vittrup Man after his DNA revealed that he was genetically distinct from the other.r. A study detailing their findings appeared in February 2024 in the journal PLOS One. [Source: Ashley Strickland, CNN, February 16, 2024]

“I wanted to make an anonymous skull speak (and) find the individual behind the bone. The initial result(s) were ‘almost too good to be true’, which made me apply additional and alternative methods. The outcome was this surprising life history,” said lead study author Anders Fischer, project researcher in the department of historical studies at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden and director of Sealand Archaeology,.

Ashley Strickland wrote in CNN: The research team, eager to uncover as many clues as possible about the life of Vittrup Man, analyzed his tooth enamel, tartar and bone collagen using cutting-edge analytical methods. The combined detection of specific chemical elements within his enamel, such as strontium, nitrogen, carbon and oxygen, as well as a protein analysis of his teeth and bones, revealed how Vittrup Man’s diet went from being that of a hunter-gatherer to a farmer before dying between the ages of 30 and 40.

Vittrup Man was likely born and grew up along the coast of the Scandinavian Peninsula, perhaps within the frigid climes of Norway or Sweden. He was genetically closest to people from those regions and had darker skin than the Stone Age communities in Denmark. In Scandinavia, Vittrup Man likely belonged to a northern hunter-gatherer community that enjoyed a diet of fish, seals and even whales, which suggests that the foragers had vessels that enabled them to fish in the open sea. And then, something caused his life to change drastically, and by the age of 18 or 19, Vittrup Man was in Denmark and subsisting on the diet of a farmer, eating sheep and goat.

His journey to a farming peasant society in Denmark “indicates extensive travel by boat,” the study authors said. Vittrup Man’s long-distance movements were unusual, “but may say something about ongoing exchanges between Danish farmers and northern hunter-gatherers,” said study coauthor Karl-Göran Sjögren, researcher in the department of historical studies at the University of Gothenburg.

Why Vittrup Man made such a long voyage is unknown, but the researchers have a couple of theories. It’s possible that he was a captive or a slave who became part of local society in Denmark. Or Vittrup Man was a trader who settled in Denmark. Archaeologists have known that flint axes were traded from Denmark to the Arctic Circle in Norway, said study coauthor Lasse Sørensen, head of research of ancient cultures of Denmark and the Mediterranean at the National Museum in Copenhagen. “The study adds a concrete human being of flesh and blood to this finding,” Sørensen said.

Egtved Girl — the 3,300 Female Scandinavian Vagabond

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Since her remains were discovered in 1921 near the town of Egtved, Denmark, almost 3,300 years after she died at around 17, the young woman was thought to have been a local, and became known as the “Egtved Girl.” But new research has undermined this assumption. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

“Based on the strontium isotope signature of one of the girl’s first molars, which was fully formed by age four, a team led by Karin Frei of the National Museum of Denmark has determined that she could not have grown up on the Jutland Peninsula, where Egtved is located. Instead, she was most likely raised in the Black Forest region of southern Germany, some 500 miles away. There were well established ties between the two areas at the time, and the researchers believe the girl was sent to marry a chieftain in Jutland to further the alliance.

“Strontium isotope signatures from the girl’s hair and fingernail provide a detailed record of her travels in the last two years of her life. During this period she appears to have moved from her homeland to Jutland, back to where she grew up, and then to Jutland once again shortly before she died. “This tells us that people in the Bronze Age really moved around,” says Frei, “not only men, but women as well.”

6,500-Year-Old Arctic Graveyard Found in Finland

In an article published December 1, 2023 in the journal Antiquity, archaeologists said they may have found one of the largest prehistoric hunter-gatherer cemeteries in northern Europe just south of the Arctic Circle. According to Live Science: In 1959, local workers stumbled on stone tools in Simo, Finland, which is near the northern edge of the Baltic Sea just 50 miles (80 kilometers) south of the Arctic Circle. The archaeological site, called Tainiaro, was partially excavated in the 1980s, revealing thousands of artifacts, including animal bones, stone tools and pottery. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, December 1, 2023]

Archaeologists also noticed 127 possible pits of various sizes that have since been filled in with sediment. Some contained evidence of burning, and some had traces of red ochre, a natural pigment from iron that is a key characteristic of many Stone Age burials. Without evidence of skeletons, which decay quickly in this region's acidic soil, however, the identification of Tainiaro as a cemetery was never proved. But after reanalyzing old records and undertaking new fieldwork, a team of researchers is proposing that Tainiaro was most likely a large cemetery dating back to the fifth millennium B.C., making it the northernmost Stone Age cemetery ever found.

For most of prehistory, this area of the world was occupied by people practicing a mainly foraging lifestyle as hunters, gatherers and fishers. Archaeologists found thousands of burnt animal bones at Tainiaro; most were from seals, but some came from beaver, salmon and reindeer, hinting at the variety of meat in the Stone Age diet and a probable domestic occupation of the site.

But initially, archaeologists were unsure if the pit features were hearths, graves or a mix of both. To clarify the nature of the 127 pits, the team, led by Aki Hakonen, an archaeologist at the University of Oulu in Finland, compared the pits' sizes and contents to those of hundreds of Stone Age graves across 14 cemeteries. They determined that at least 44 of the pits were likely to have contained human burials; the rounded-edged rectangular shapes of the pits, coupled with traces of red ochre and an occasional artifact, suggest a high probability that the pits were indeed graves. "Tainiaro should, in our opinion, be considered to be a cemetery site," the authors wrote, "even though no skeletal material has survived at Tainiaro."

Based on the shapes of burial pits at other sites, the deceased at Tainiaro may have been buried on their backs or on their sides, with their knees bent, Hakonen said. "There would have been furs," he told Live Science, and "the deceased could have been wrapped in [seal] skins." Food, grave goods and red ochre also could have been mixed into the grave or the fill dirt, Hakonen noted.

Ulla Moilanen, an archaeologist at the University of Turku in Finland told Live Science that the authors' interpretations of Tainiaro are convincing. "Sometimes, it is difficult to say what kind of features can be interpreted as graves," she said, but "this paper provides excellent tools for studying poorly preserved material and is a very good starting point to study this and other similar sites more carefully." "This study is much welcomed," Marja Ahola, an archaeologist at the University of Oulu, who was not involved in the present study, told Live Science. Hakonen and colleagues can use the information they learned in this study to "bring forth important new insights into Stone Age funerary practices in the subarctic north of the Baltic Sea," Ahola said.

Only one-fifth of Tainiaro has been excavated, so the total number of graves could be higher — possibly more than 200. But the team is still testing whether ground-penetrating radar, which uses radar pulses to detect underground anomalies, could be helpful, because "no one wants to destroy the whole site," Hakonen said. There is even a chance, according to Hakonen, that future work may reveal human skeletons, particularly if a grave was covered in red ochre, as it can preserve organic remains.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except fermented fish from Adam Boethius, Lund University and fish traps from Museum of Cultural History in Oslo (KHM)

Text Sources: National Geographic, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024