Home | Category: Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe

NESS OF BRODGAR

Ring of Brodgar

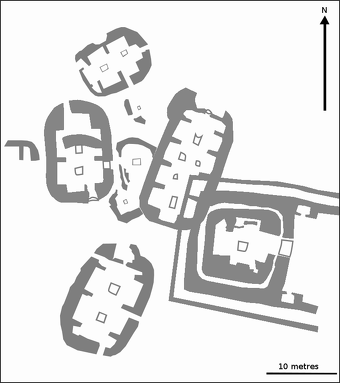

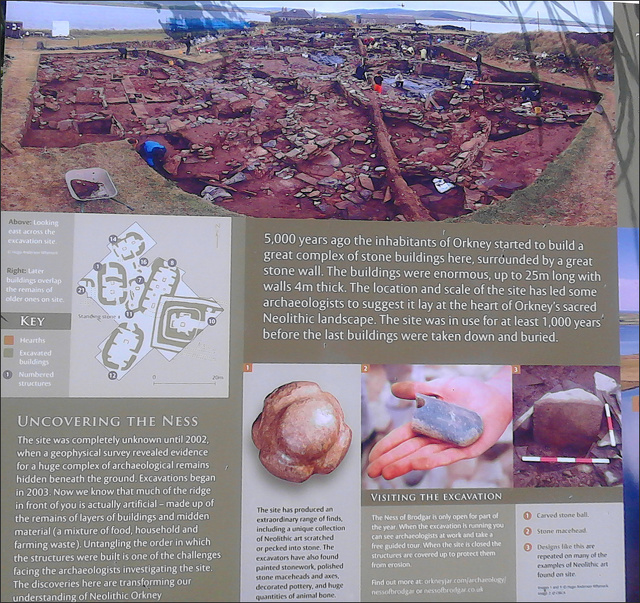

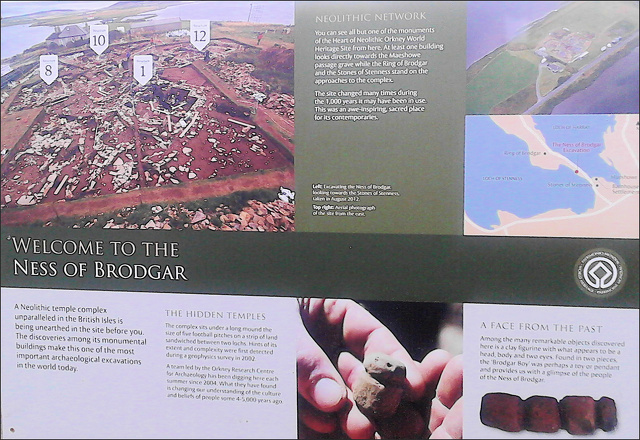

The Ness of Brodgar is an archaeological site covering 2.5 hectares (6.2 acres) between the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness in the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site on the main Island of Orkney, Scotland. First surveyed in 2003, with major excavations beginning in 2008, .the site features decorated stone slabs, a six-meter (20-foot) thick wall with foundations, and a large building described as a Neolithic temple. Carbon dating of animal bone, wood, and charcoal indicates at the site was continuous occupied for least 1,000 years from around 3300 to 2300 B.C., and probably used longer than that. There are many examples of one structure built on top of another structure.

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: Seen from a specially erected viewing platform, the site is a crazy patchwork of overlapping rectangles, like a carelessly scattered pack of cards, with each rectangle delineated by a substantial stone wall. Peeking out from the bottom of this pile are the early structures, and later additions slice over them, culminating in a vast, double-walled building. Hundreds of panels of elaborately carved artwork have emerged from this spectacular construction — marking it as a truly extraordinary place. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

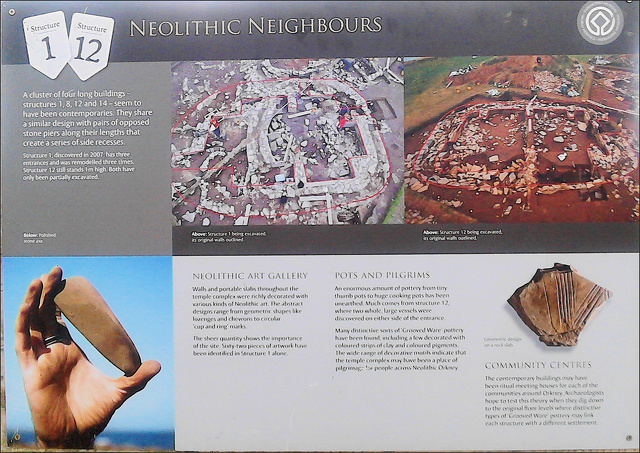

The earliest structures are a series of oval-shaped stone buildings dating to around 3000 B.C. In most cases, only fragments of the buildings have been excavated, with the remainder still buried beneath later structures. However, the fragments suggest that the buildings were divided into different areas by upright slabs arranged in a radial pattern like the spokes on a bicycle wheel. In at least one of these buildings there was a hearth in the center, and in some there were a few sherds of what is known as “Grooved Ware” pottery.

“What really sets these buildings apart from other known Neolithic settlements is the enclosure by a massive stone wall — 13 feet wide — with a ditch running along the outside of it. “The wall has beautiful stonework on the side facing the Ring of Brodgar,” says archaeologist Nick Card. Meanwhile, south of the site, what is assumed to be the continuation of this wall has also been uncovered, rising to at least six feet tall, with similarly exquisite stonework and a flagstone pathway at its base. “The walls emphasize the importance of what was happening here, and as with us today, the Neolithic people approaching this enclosure must have felt a sense of wonderment and awe,” he continues.

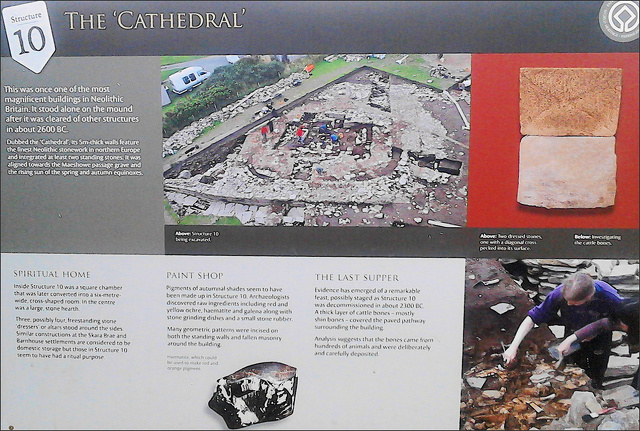

The southern boundary wall at the Ness of Brodgar rises to at least two meters high and features immaculate stonework. A layer of flat stone slates is what remains of a roof that collapsed around 2800 B.C. It is the earliest known slate roof in Britain, and one of Orkney’s many Neolithic innovations. The cross-shaped chamber at the center of Structure 10, also known as the “cathedral,” represents the final phase of architectural development at the Ness of Brodgar.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Orcadia: Land, Sea and Stone in Neolithic Orkney” by Mark Edmonds (2019) Amazon.com;

“Orkney: A Historical Guide” (Birlinn Historical Guides) by Caroline Wickham-Jones (2015) Amazon.com;

“Monuments of Orkney: A Visitor's Guide” (Explore Scottish Monuments)

by Caroline Wickham-Jones Amazon.com;

“Skara Brae” (Historic Scotland: Official Souvenir Guide) Illustrated, (2020)

Amazon.com;

“Skara Brae: Prehistoric Village” by Olivier Dunrea (1986) Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Britain: The Transformation of Social Worlds” (Oxford Handbooks)

by Keith Ray and Julian Thomas (2018) Amazon.com;

“The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World” by Paul Pettitt, Mark White Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Cultures of the British Isles” by Stuart Piggott (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic of Britain and Ireland” by Vicki Cummings (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Stonehenge People: An Exploration of Life in Neolithic Britain 4700-2000 BC”

by Rodney Castleden (2002) Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Life and Death in the Yorkshire Dales (British)” (2024) by Deborah Hallam Amazon.com;

“Wild Ruins B.C.: The Explorer's Guide to Britain's Ancient Sites” by Dave Hamilton (2019) Amazon.com

“The Old Stones: A Field Guide to the Megalithic Sites of Britain and Ireland” by Andy Burnham (2018) Amazon.com;

“Stonescapes: A Field Guide to Sacred Stones of Ireland and Scotland” by Aaron B. Christian PhD (2025) Amazon.com;

“Life in Copper Age Britain” by Julian Heath (2013) Amazon.com;

“Fragments of the Bronze Age: The Destruction and Deposition of Metalwork in South-West Britain and Its Wider Context” by Matthew G. Knight (2022) Amazon.com;

“Personifying Prehistory: Relational Ontologies in Bronze Age Britain and Ireland” by Joanna Bruck (2019) Amazon.com;

“Secret Britain: Unearthing Our Mysterious Past” by Mary-Ann Ochota (2020) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age Worlds: A Social Prehistory of Britain and Ireland” by Robert Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

Monuments of the Orkney Islands

The Orkney Islands is a group of quiet, wind blown islands just off the north of Scotland. They are arguably the place where British culture began. According to UNESCO: “The Orkney Islands lie 15 kilometers north of the coast of Scotland. The group of Neolithic monuments on Orkney consists of a large chambered tomb (Maes Howe), two ceremonial stone circles (the Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar) and a settlement (Skara Brae), together with a number of unexcavated burial, ceremonial and settlement sites. The group constitutes a major prehistoric cultural landscape which gives a graphic depiction of life in this remote archipelago in the far north of Scotland some 5,000 years ago. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage sites website =]

“The monuments are in two areas, some 6.6 kilometers apart on the island of Mainland, the largest in the archipelago. The group of monuments that make up the Heart of Neolithic Orkney consists of a remarkably well-preserved settlement, a large chambered tomb, and two stone circles with surrounding henges, together with a number of associated burial and ceremonial sites. The group constitutes a major relict cultural landscape graphically depicting life five thousand years ago in this remote archipelago. =

“The four monuments that make up the Heart of Neolithic Orkney are unquestionably among the most important Neolithic sites in Western Europe. These are the Ring of Brodgar, Stones of Stenness, Maeshowe and Skara Brae. They provide exceptional evidence of the material and spiritual standards as well as the beliefs and social structures of this dynamic period of prehistory. =

See Separate Articles: ORKNEY ISLANDS NEOLITHIC SITES: HISTORY, TOMBS, ART, BUILDINGS europe.factsanddetails.com

Temple Complex of Ness of Brodgar

On the temple complex of the Ness of Brodgar, Robin McKie wrote in The Observer: “Its size, complexity and sophistication have left archaeologists desperately struggling to find superlatives to describe the wonders they found there. "We have discovered a Neolithic temple complex that is without parallel in western Europe. Yet for decades we thought it was just a hill made of glacial moraine," says discoverer Nick Card of the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology."In fact the place is entirely manmade, although it covers more than six acres of land." [Source: Robin McKie, The Observer, October 6, 2012 |+|]

“Once protected by two giant walls, each more than 100m long and 4m high, the complex at Ness contained more than a dozen large temples – one measured almost 25m square – that were linked to outhouses and kitchens by carefully constructed stone pavements. The bones of sacrificed cattle, elegantly made pottery and pieces of painted ceramics lie scattered round the site. The exact purpose of the complex is a mystery, though it is clearly ancient. Some parts were constructed more than 5,000 years ago. "This wasn't a settlement or a place for the living," says archaeologist Professor Colin Richards of Manchester University, who excavated the nearby Barnhouse settlement in the 1980s. "This was a ceremonial centre, and a vast one at that. But the religious beliefs of its builders remain a mystery." |+|

Standing stones as the Ring of Brodgar

“What is clear is that the cultural energy of the few thousand farming folk of Orkney dwarfed those of other civilisations at that time. In size and sophistication, the Ness of Brodgar is comparable with Stonehenge or the wonders of ancient Egypt. Yet the temple complex predates them all. The fact that this great stately edifice was constructed on Orkney, an island that has become a byword for remoteness, makes the site's discovery all the more remarkable. For many archaeologists, its discovery has revolutionised our understanding of ancient Britain. |+|

“But it is not just the dimensions that have surprised and delighted archaeologists. Two years ago, their excavations revealed that haematite-based pigments had been used to paint external walls – another transformation in our thinking about the Stone Age. "We see Neolithic remains after they have been bleached out and eroded," says Edmonds. "However, it is now clear from Brodgar that buildings could have been perfectly cheerful and colourful." |+|

“Equally puzzling was the fate of the complex. Around 2,300 B.C., roughly a thousand years after construction began there, the place was abruptly abandoned. Radiocarbon dating of animal bones suggests that a huge feast ceremony was held, with more than 600 cattle slaughtered, after which the site appears to have been decommissioned. Perhaps a transfer of power took place or a new religion replaced the old one. Whatever the reason, the great temple complex – on which Orcadians had lavished almost a millennium's effort – was abandoned and forgotten for the next 4,000 years.” |+|

Features of the Buildings at Ness of Brodgar

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: One of the buildings, known as Structure 8, has been excavated down to floor level across half of the interior, providing clues as to how the building was used. The building, which measures 60 by 29 feet, contains four pairs of stone piers, creating 10 alcoves. The central area contains at least three hearths, and is divided by a number of upright slabs. “These buildings really have architecture: They have been planned, laid out, and designed,” says Card. Interestingly, a similar architecture is seen in many of Orkney’s Neolithic tombs, such as the Midhowe and Unstan tombs. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

“The combination of hearths, piers, and upright slabs would have guided people’s passage through the buildings and defined how different parts of the building were used,” explains Roy Towers of the University of the Highlands and Islands.“Inside the building, Card and his colleagues found evidence of interior decoration. A number of stones are incised with geometric patterns, and others have remnants of different-colored pigments on them — the oldest evidence of painted walls in northern Europe.

Archaeologists also uncovered a layer of hundreds of thin rectangular stone slates, just above the floor level. They all had carefully trimmed edges; the only plausible explanation was that they were slates from a roof that collapsed in 2800 B.C. This is the first evidence for a Neolithic slate roof in Britain, and contradicts the prior assumption that all roofs from this period were thatched. Unlike steeper modern slate roofs, this one probably had a low pitch, with clay used to seal gaps. Orkney doesn’t have many large trees, but roof trusses may have been made with wood from Scandinavia and the Baltic, as well as big pieces of North American driftwood riding the Gulf Stream.

“Some archaeologists speculate that different buildings at the Ness of Brodgar would have belonged to different “clans” or settlements. “Just as stones from different places form the Ring of Brodgar, I suspect that particular groups are present at the Ness site by way of ‘big houses,’ or ‘holy houses’ as they have been called,” says Colin Richards from the University of Manchester, who excavated the Barnhouse settlement.

Artifacts Found at Ness of Brodgar

Sherds of “Grooved Ware” pottery have been found at the Ness of Brodgar site. The style may have originated in Orkney before spreading across Britain and Ireland. A beautifully polished stone ax is among many exceptional objects recovered from inside ceremonial buildings at the Ness of Brodgar. Its workmanship and location suggest some sort of ritual purpose.

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The roof collapse appears to have taken place while the building was still in use, encasing a variety of unusual items exactly where they had been left 4,800 years ago. In some of the alcoves, Card and his team have found exotic items, including a whalebone mace-head, stone mace-heads, a whale tooth, and polished stone axes and tools, along with more familiar items such as animal bones and pottery.

The unusual assemblage appears to have been positioned deliberately and carefully. “It looked like people had left these things and intended to come back to them, or they were votive offerings to mark the end of this building,” says Card. Similar prized objects have also emerged from the other contemporary structures, including a stunning polished stone ax discovered in another building, Structure 14, during the 2012 dig season. “It is a magnificently colored metamorphic rock, bluey-black as a background, interleaved with puffy white clouds of quartz. Looking at it is like lying on your back gazing at a summer sky,” Towers says. The huge amount of time, effort, and energy that went into making these highly prized items, their location within the buildings, and the special status of the buildings themselves, all point toward these objects being used in some kind of ceremony or ritual.

Design of the Main Temple at Ness of Brodgar

The main Ness of Brodgar temple is sometimes called the "Cathedral". Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Measuring 82 by 66 feet (roughly the size of two tennis courts), and with walls nearly 13 feet thick, this structure was a serious status symbol. “This definitely wasn’t an ordinary building; it was way beyond the norm. It would have been the finest bit of architecture in northern Europe at the time,” says Card. The “Neolithic cathedral,” as it has been nicknamed (Structure 10, formally), had a wide flagstone pavement around the outside of it and an entrance forecourt, leading to a doorway flanked by two standing stones. Inside the building, archaeologists have traced the remnants of a square central chamber about 26 feet across. The masonry was exceptional, with extensive use of dressed stone and imperfections removed by pecking them away with stone hammers. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

“Standing in front of the remains of the Neolithic cathedral, it seems barely plausible that such a building could have been built using only stone tools. More incredible still is that enough men could be spared for its construction (as they had been for the two mammoth stone circles nearby). “The scale of the structures tells us that it was a society that could mobilize lots of people and provide for them by creating surpluses,” says Card. Despite living in a seemingly remote place, this thriving population of linked communities appears to have been Stone Age movers and shakers. They came up with new ideas, designs, beliefs, and ways of doing things that spread far and wide across Britain. The Ness of Brodgar ceremonial complex, including the Ring of Brodgar and Standing Stones of Stenness, is a fine example of a new social and cultural trend, with the Ness predating England’s most famous stone circle and ceremonial complex at Stonehenge by at least a couple of hundred years. Meanwhile, Neolithic Grooved Ware — style pottery is also thought to have had its origins in Orkney before spreading across Britain and Ireland. And inside their buildings the Neolithic people of Orkney started a colorful trend, decorating sections of their walls with red, black, and white paints.

“The design of the cathedral may have been on the cutting edge of Neolithic Britain, but it didn’t stay the same for long. By around 2400 B.C., the original inner chamber was remodeled, and a cross-shaped chamber, 21 feet across, was put in its place, incorporating colorful local red and yellow sandstone. Strangely, though, the masonry wasn’t up to previous standards, making the walls a bit uneven. “It is a bit perplexing, as this secondary phase is a bit of a ‘cowboy’ build,” says Card. The inconsistency in the walls might be due to subsidence into earlier underlying structures, and the remodeling may have been an attempt to shore the walls up. “Throughout the period, the buildings reflect a gradual rise and centralization of power, and the rise of an elite culminating in a truly hierarchical society by the time of Structure 10,” explains Card.

Construction of a Ness Brodgar Temple

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Over time, the interaction of the different communities at the Ness of Brodgar may have contributed to a more cohesive, less fragmented form of society — a transition also visible in the architecture of the site. Around 2500 B.C., construction began on a single, truly gargantuan building. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

Roff Smith wrote in National Geographic: “One long-ago day around 3200 B.C., the farmers and herdsmen on Scotland’s remote Orkney Islands decided to build something big. They had Stone Age technology, but their vision was millennia ahead of their time. [Source: Roff Smith, National Geographic, August 2014 ]

“They quarried thousands of tons of fine-grained sandstone, trimmed it, dressed it, then transported it several miles to a grassy promontory with commanding views of the surrounding countryside. Their workmanship was impeccable. The imposing walls they built would have done credit to the Roman centurions who, some 30 centuries later, would erect Hadrian’s Wall in another part of Britain. \=/

“Cloistered within those walls were dozens of buildings, among them one of the largest roofed structures built in prehistoric northern Europe. It was more than 80 feet long and 60 feet wide, with walls 13 feet thick. The complex featured paved walkways, carved stonework, colored facades, even slate roofs—a rare extravagance in an age when buildings were typically roofed with sod, hides, or thatch. Although it’s usually referred to as a temple, it’s likely to have fulfilled a variety of functions during the thousand years it was in use. It’s clear that many people gathered here for seasonal rituals, feasts, and trade. \=/

“For a thousand years, a span longer than Westminster Abbey and Canterbury Cathedral have stood, the temple complex on the Ness of Brodgar cast its spell over the landscape—a symbol of wealth, power, and cultural energy. To generations of Orcadians who gathered there, and to the travelers who came hundreds of miles to admire it and conduct business, the temple and its walled compound of buildings must have seemed as enduring as time itself. \=/

Purpose of Ness of Brodgar

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The presence of this imposing wall suggests that the buildings at the Ness of Brodgar were more than ordinary family homes. Furthermore, the location, on a natural land bridge that links the Ring of Brodgar to the Stones of Stenness (both constructed around the same time as the boundary wall), seems significant. “It feels very central to the landscape here, in the middle of a huge natural amphitheater created by the hills around, and with water on either side. There is nowhere else quite like it,” says Card. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

“This spectacular setting, the relationships among the Ness buildings, the imposing exterior wall, and the proximity to other ceremonial sites, including the stone circles and Maes Howe tomb, suggest that the Ness of Brodgar held a powerful place in the spiritual lives of these people. While excavations at villages such as Skara Brae and Barnhouse have revealed much about their everyday lives, little is known of the political and spiritual aspects of their culture and society.

One suggestion, put forward by Mike Parker Pearson, an archaeologist at University College London, is that the Ness ceremonial complex separated the “land of the living” at the Stones of Stenness, from the “land of the ancestors” at the Ring of Brodgar, and thus represented a place of transition. Card thinks this is plausible, and wonders if each nearby community had its own special building at the Ness site. “I think that these communities may have been fiercely competitive, each trying to outdo each other, with visible shows of prestige and power,” he says.

Worship at the Main Temple at Ness of Brodgar

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: “So what did these “elite” people do in the cathedral? Inside each of the recesses of the central chamber, Card and his team have uncovered stone shelves (locally known as “dressers,” and also found in high-status buildings at a number of other Neolithic sites), which may have functioned like altars. In the center of the chamber was a hearth with a cow skull placed upside down in the middle. And like the earlier buildings with piers and alcoves, a number of exotic items, such as beautifully polished stone axes and mace-heads have emerged from the cruciform chamber. Could these objects have been some kind of ritual offerings? Were the people entering this inner sanctum the Neolithic equivalent of priests? [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

“We’ll never know exactly what happened inside these unusual buildings, but whatever it was it came to an abrupt, perhaps spectacular, end. When Card and his colleagues excavated down to the pavement level around Structure 10, they were stunned to recover the shinbones of hundreds of cattle — enough to have fed thousands of people.

Carbon dating of the bones has revealed that this huge feast took place around 2300 B.C. — approximately the same time as the very large eruption of an Icelandic volcano called Hekla, which may have had cataclysmic climate consequences across northern Europe. The timing could be a coincidence, or possibly this feast was the Orkney way of ushering in the end of the world. Alternatively, this “decommissioning” of the cathedral may have been a celebration of a fresh start, ushering in Bronze Age technology, new forms of pottery, new beliefs, and new burial practices. For now, the answers remain underground.

How the Temples at Ness of Brodgar Were Used

Robin McKie wrote in The Observer: “The men and women who built at the Ness also used red and yellow sandstone to enliven their constructions. (More than 3,000 years later, their successors used the same materials when building St Magnus' Cathedral in Kirkwall.) But what was the purpose of their construction work and why put it in the Ness of Brodgar? Of the two questions, the latter is the easier to answer – for the Brodgar headland is clearly special. "When you stand here, you find yourself in a glorious landscape," says Card. "You are in the middle of a natural amphitheatre created by the hills around you." [Source: Robin McKie, The Observer, October 6, 2012 |+|]

“The surrounding hills are relatively low, and a great dome of sky hangs over Brodgar, perfect for watching the setting and rising of the sun, moon and other celestial objects. (Card believes the weather on Orkney may have been warmer and clearer 4,000 to 5,000 years ago.) Cosmology would have been critical to society then, he argues, helping farmers predict the seasons – a point supported by scientists such as the late Alexander Thom, who believed that the Ring of Brodgar was an observatory designed for studying the movement of the moon. |+|

“These outposts of Neolithic astronomy, although impressive, were nevertheless peripheral, says Richards. The temple complex at the Ness of Brodgar was built to be the most important construction on the island. "The stones of Stenness, the Ring of Brodgar and the other features of the landscape were really just adjuncts to that great edifice," he says. Or as another archaeologist put it: "By comparison, everything else in the area looks like a shanty town." |+|

“For a farming community of a few thousand people to create such edifices suggests that the Ness of Brodgar was of profound importance. Yet its purpose remains elusive. The ritual purification of the dead by fire may be involved, suggests Card. As he points out, several of the temples at Brodgar have hearths, though this was clearly not a domestic dwelling. In addition, archeologists have found that many of the stone mace heads (hard, polished, holed stones) that litter the site had been broken in two in exactly the same place. "We have found evidence of this at other sites," says Richards. "It may be that relatives broke them in two at a funeral, leaving one part with the dead and one with family as a memorial to the dead. This was a place concerned with death and the deceased, I believe." |+|

Archaeological Work at Ness of Brodgar

Nick Card of the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology head the excavation of Ness of Brodgar. Since 2008 he and his team have dug for six weeks at the site every summer. Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology magazine: As of 2013, they had identified more than 20 structures, and observed even more through geophysical tests such as magnetometer surveys and ground-penetrating radar, all enclosed by the remains of a thick boundary wall delineating a six-acre complex — the size of three soccer pitches. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

The whole thing is sitting on a jelly of earlier structures,” says Card. “What we are seeing really is just the tip of the iceberg.” So far the archaeologists have concentrated on a small portion of the site and only excavated down to the floor level of the uppermost structures. In the layers of building foundations, Card and his team are seeing a clear progression in building style and architecture — a pattern they think may reflect some of the changes occurring in Neolithic society over that time.

Roff Smith wrote in National Geographic: “The first hint of big things underfoot at the Ness came to light in 2002, when a geophysical survey revealed the presence of large, man-made anomalies beneath the soil. Test trenches were dug and exploratory excavations begun, but it wasn’t until 2008 that archaeologists began to grasp the scale of what they had stumbled upon. As of 2014, only 10 percent of the Ness has been excavated, with many more stone structures known to be lurking under the turf nearby. [Source: Roff Smith, National Geographic, August 2014 ]

Card told The Observer: "Being given World Heritage status meant we had to think about the land surrounding the sites. "We decided to carry out geophysical surveys to see what else might be found there." Robin McKie wrote in The Observer: Such surveys involve the use of magnetometers and ground-penetrating radar to pinpoint manmade artefacts hidden underground. And the first place selected by Card for this electromagnetic investigation was the Ness of Brodgar. [Source: Robin McKie, The Observer, October 6, 2012 |+|]

“The ridge was assumed to be natural. However, Card's magnetometers showed that it was entirely manmade and bristled with features that included lines of walls, concentric pathways and outlines of large buildings. "The density of these features stunned us," says Card. At first, given its size, the team assumed they had stumbled on a general site that had been in continuous use for some time, providing shelter for people for most of Orkney's history, from prehistoric to medieval times. "No other interpretation seemed to fit the observations," adds Card. But once more the Ness of Brodgar would confound expectations. |+|

“Test pits, a metre square across, were drilled in lines across the ridge and revealed elaborate walls, slabs of carefully carved rock, and pieces of pottery. None came from the Bronze Age, however, nor from the Viking era or medieval times. Dozens of pits were dug over the ridge, an area the size of five football pitches, and every one revealed items with a Neolithic background.

Then the digging began in earnest and quickly revealed the remains of buildings of startling sophistication. Carefully made pathways surrounded walls – some of them several metres high – that had been constructed with patience and precision. "It was absolutely stunning," says Colin Richards. "The walls were dead straight. Little slithers of stones had even been slipped between the main slabs to keep the facing perfect. This quality of workmanship would not be seen again on Orkney for thousands of years." |+|

“Slowly the shape and dimensions of the Ness of Brodgar site revealed themselves. Two great walls, several metres high, had been built straight across the ridge. There was no way you could pass along the Ness without going through the complex. Within those walls a series of temples had been built, many on top of older ones. "The place seems to have been in use for a thousand years, with building going on all the time," says Card.

“More than a dozen of these temples have already been uncovered though only about 10% of the site has been fully excavated so far. "We have never seen anything like this before," says York University archaeologist Professor Mark Edmonds. "The density of the archaeology, the scale of the buildings and the skill that was used to construct them are simply phenomenal. There are very few dry-stone walls on Orkney today that could match the ones we have uncovered here. Yet they are more than 5,000 years old in places, still standing a couple of metres high. This was a place that was meant to impress – and it still does."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024