Home | Category: First Modern Humans / Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe

MESOLITHIC PERIOD

reconstruction of a Mesolithic hunter gatherer's camp, circa 7000 BC, at Irish National Heritage Park

The Mesolithic Period (Middle Stone Age) was an archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic primarily used to describe Europe and the Middle East. It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures before the arrival of agriculture in these regions between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. It extends roughly from 15,000 to 5,000 years ago in Europe; and from 20,000 to 10,000 years ago in the Middle East. But other dates are used. Some say the the Mesolithic period extends from 10,000 to 4000 B.C. in Europe. The term is less used of areas farther east, and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus. The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia. [Source: Wikipedia]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Until recently, Mesolithic peoples have remained something of an enigma to archaeologists and have been largely overlooked. The people of the earlier Paleolithic period are lauded for their finely crafted stone tools and sophisticated art, such as the cave paintings in Lascaux, France, while the Neolithic age, which followed the Mesolithic, saw the widespread introduction of agriculture and the first permanent settlements. Because Mesolithic societies were mostly nomadic, they left behind very few identifiable archaeological sites. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

Their material culture consisted largely of small arrowheads and points, which scholars have considered unimpressive compared to those of the Paleolithic people who preceded them and the Neolithic people who followed. “They didn’t create beautiful cave art and they didn’t have settlements like the Neolithic farmers,” says Luc Amkreutz, curator of prehistoric collections at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden in the Netherlands. “In most cases, only the lithics survive, so it’s a very difficult story to tell.”

According to Live Science and National Geographic: The Mesolithic period for humans was a time of severe climate change across the world. At this time, the ice sheets that covered much of northern Europe, Asia and North America began to melt away, creating new lands that became populated by animal herds and people. About 14,500 years ago, as Europe began to warm, humans followed the retreating glaciers north. In the ensuing millennia, they developed more sophisticated stone tools and settled in small villages. [Sources: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019; Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 24, 2019]]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oxford Handbook of Mesolithic Europe” by Liv Nilsson Stutz, Rita Peyroteo Stjerna, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000–5000 BC” by Steven Mithen (2006) Amazon.com;

“Coastal Landscapes of the Mesolithic: Human Engagement with the Coast from the Atlantic to the Baltic Sea” by Almut Schülke (2020) Amazon.com;

“Doggerland: Lost World under the North Sea” by Luc W.S.W. Amkreutz and Sasja Van der Vaart-Verschoof (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesolithic Europe” by Geoff Bailey and Penny Spikins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene—Holocene Transition” by Lawrence Guy Straus, Berit Valentin Eriksen (1996) Amazon.com

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Iberia: Genetics, Anthropology, and Linguistics” by Jorge Martínez-Laso, Eduardo Gómez-Casado (2000) Amazon.com;

“The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World” by Paul Pettitt, Mark White Amazon.com;

Doggerland

Doggerland refers to a vast area between present-day England and the Netherlands that was exposed when the ice sheets there melted around 18,000 years ago was submerged by the sea about 12,000 years ago, when the level of the North Sea rose as more Ice Are glaciers melted. Archaeologists have found human remains and artifacts have been dredged up or pulled up by fishermen. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 24, 2019]

Fisherman working in North Sea primarily off the Dutch coast were the first to notice signs of Doggerland. They occasionally dragged up bones and artifacts that appeared to have been connected to people that lived during the last Ice Age when sea levels were lower and migrated to higher ground when sea levels rose.

Laura Spinney wrote in National Geographic: “When signs of a lost world at the bottom of the North Sea first began to appear, no one wanted to believe them. The evidence started to surface a century and a half ago, when fishermen along the Dutch coast widely adopted a technique called beam trawling. They dragged weighted nets across the seafloor and hoisted them up full of sole, plaice, and other bottom fish. But sometimes an enormous tusk would spill out and clatter onto the deck, or the remains of an aurochs, woolly rhino, or other extinct beast. The fishermen were disturbed by these hints that things were not always as they are. What they could not explain, they threw back into the sea. [Source: Laura Spinney, National Geographic, December 2012]

“The story of that vanished land begins with the waning of the ice. Eighteen thousand years ago, the seas around northern Europe were some 400 feet lower than today. Britain was not an island but the uninhabited northwest corner of Europe, and between it and the rest of the continent stretched frozen tundra. As the world warmed and the ice receded, deer, aurochs, and wild boar headed northward and westward. The hunters followed. Coming off the uplands of what is now continental Europe, they found themselves in a vast, low-lying plain.

See Separate Article: DOGGERLAND europe.factsanddetails.com

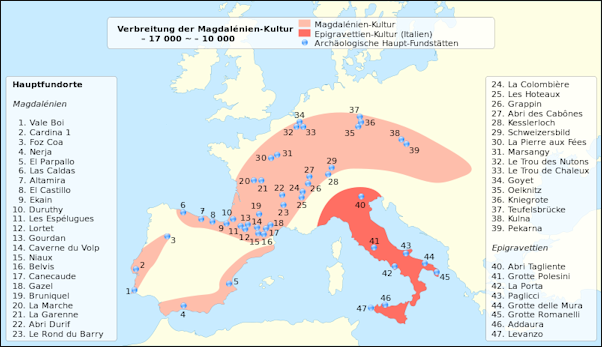

Magdalenian Culture

The Magdalenian Period (17,000 to 12,000 years ago) is named after the French site — La Madeleine, a rock shelter in the Vézère valley, in the Dordogne region of France — that tools associated with it were found. The site has tools, weapons and adornment associated with it. The culture existed toward the end of the last ice age.

According to Les Eyzies Tourist Information: “The Magdalenien is characterised by regular blade industries struck from carinated cores. Typologically the Magdalenian is divided into six phases which are generally agreed to have chronological significance. The earliest phases are recognised by the varying proportion of blades and specific varieties of scrapers, the middle phases marked by the emergence of a microlithic component (particularly the distinctive denticulated microliths) and the later phases by the presence of uniserial (phase 5) and biserial ‘harpoons’ (phase 6) made of bone, antler and ivory. [Source: leseyzies-tourist.info +/]

“By the end of the Magdalenian, the lithic technology shows a pronounced trend towards increased microlithisation. The bone harpoons and points are the most distinctive chronological markers within the typological sequence. As well as flint tools, the Magdalenians are best known for their elaborate worked bone, antler and ivory which served both functional and aesthetic purposes including bâtons de commandement. Examples of Magdalenian mobile art include figurines and intrically engraved projectile points, as well as items of personal adornment including sea shells, perforated carnivore teeth (presumably necklaces) and fossils. +/

Homo Sapiens in Europe Magdalenian distribution

“The sea shells and fossils found in Magdalenian sites can be sourced to relatively precise areas of origin, and so have been used to support hypothesis of Magdalenian hunter-gatherer seasonal ranges, and perhaps trade routes. Cave sites such as the world famous Lascaux contain the best known examples of Magdalenian cave art. The site of Altamira in Spain, with its extensive and varied forms of Magdalenian mobillary art has been suggested to be an agglomeration site where multiple small groups of Magdalenian hunter-gatherers congregated.” +/

Magdalenians Practiced Ritual Cannibalism

The Magdalenians made cave paintings, bone harpoons, sewing needles, and animal figurines sculpted from mammoth ivory. They also appear to may have practiced ritual cannibalism. Bridget Alex wrote in Archaeology magazine: While examining bones from the Magdalenian site of Gough’s Cave in England, Silvia Bello, a paleoanthropologist at London’s Natural History Museum, discovered human skulls shaped into cups, parts of skeletons that had been butchered and chewed, and an arm bone engraved with a zigzag pattern. Given the decorative flourishes on the human remains and the presence of bones from more appetizing animals, she concluded the cave’s inhabitants had held funerals involving cannibalism. “They were not just eating each other because they were hungry,” says Bello. “They were doing it as part of a ritual.” [Source: Bridget Alex, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

Questions lingered over whether cannibalism occurred only at Gough’s Cave or figured more widely in the culture. “Was it just a one-off?” asks Bello. To better understand how these people treated their dead, Bello and archaeogeneticist William Marsh, also of the Natural History Museum, reviewed archaeological evidence from 59 Magdalenian sites where human remains have been uncovered. Their study revealed that sites with evidence of cannibalism outnumbered those where deliberate burials with unmodified bones have been found. In addition, at a number of sites where cannibalism appeared to have taken place, DNA analysis showed that residents shared similar ancestry that differed from that of contemporaries who buried instead of consuming their dead.

See Cannibalism Common in Late Ice Age Northwest Europe Under CANNIBALISM AMONG OUR HUMAN ANCESTORS (1.5 MILLION TO 10,000 YEARS AGO) europe.factsanddetails.com

Ocher-Covered Female Magdalenian Burial

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: A team of archaeologists scoured El Mirón Cave in northern Spain starting in 1996 and found abundant remains of prehistoric people, primarily the Magdalenians, hunter-gatherers who lived across Western Europe at the end of the last Ice Age. But it wasn’t until 2010, when they investigated a narrow space behind a large limestone block, that the cave began to reveal its greatest secret: a significant portion of the skeleton of a Magdalenian woman who had died around 18,700 years earlier at the age of 35 to 40. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

“The team, led by Lawrence Straus of the University of New Mexico and Manuel González Morales of the University of Cantabria, found that the woman’s bones were coated with ochre, a red, iron-based pigment, earning her the moniker the “Red Lady of El Mirón.” Her skull and most of her long bones were missing, but a group of researchers led by José Miguel Carretero of the University of Burgos found that her skeleton was otherwise mostly intact, suggesting she had been buried there. “This is the first more-or-less substantial human skeleton of the Magdalenian culture found in the entire Iberian Peninsula,” says Straus.

“The limestone block next to the Red Lady’s burial spot has a large number of engravings on its outer face dating to around the time she died, including several that form a distinctive “V” shape, possibly meant to represent a female pubic triangle and to indicate that a woman had been buried nearby. In addition, the inner side of the block adjacent to the burial site was covered with ochre. “You could speculate that the block may have been a marker of her grave,” says Straus.

“The researchers are unsure why such apparent effort was expended on the Red Lady after her death. “Whoever she was,” says Straus, “she was given special treatment that was different from the norm. We don’t know what the Magdalenians normally did with their bodies, but by and large they were not burying them.”

First Britons

The first people to live in Britain were Stone-Age hunter-gatherers. During much of the Stone Age, Britain was connected to the European continent by a land bridge. People traveled back and forth between the two region, following the herds of deer and horses which they hunted. Britain became permanently separated from the continent by the English Channel about 10,000 years ago. Cheddar Man, a 9,000-year-old skeleton, was found near Cheddar, England. [Source: “Life in the United Kingdom, a Guide for New Residents,” 3rd edition, Page 15, Crown 2013 /]

Hunter-gatherers dressed in animal skins roamed around Hampstead Heath near London around 8,000 years ago. Numerous prehistoric sites between 4000 B.C. and 1500 B.C. have been discovered around Britain and Scotland. Many parts of Britain contain Neolithic burial mounds and standing stones, the most famous of which is Stonehenge. In 1997, scientists found a site twice as large as Stonehenge, with stone circles remains of timber temples, at Stanton Drew in Somerset. Archeologist have found evidence that bridge made from oak crossed the Thames, where Parliament now stands in 1,500 B.C. The bridge was two feet wide and stretched at least a third of the way across the river.

Around 4,000 years ago, people in Britain learned to make bronze, marking the beginning of the Bronze Age there. At that time people lived in roundhouses and buried their dead in tombs called barrows. They were skilled metalworkers who produced bronze and gold objects, including tools, ornaments and weapons. During the Iron Age that followed, people learned how to make weapons and tools out of iron. They continued to live in roundhouses but they were grouped together in larger settlements, and sometimes were defended by hill forts. A hill fort from this era can still be seen today at Maiden Castle, in Dorset. Most people spoke a Celtic language and were either farmers, craft workers or warriors. Celtic languages were spoken throughout Europe and one closely linked to those spoken in Britain are still spoken today in some parts of Wales, Scotland and Ireland. Iron Age Britons produced the first coins to be minted in Britain, some inscribed with the names of Iron Age kings. By some reckonings, this marks the beginnings of British history. /

See Separate Articles: FIRST BRITONS europe.factsanddetails.com and MESOLITHIC BRITONS (20,000 TO 5000 YEARS AGO) europe.factsanddetails.com

Cheddar Man and Humans Who Lived in Britain 20,000 to 10,000 Years Ago

Cheddar Man skull

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “In 1903, field researchers working in the cave’s entrance uncovered Cheddar Man, the oldest complete skeleton in Britain at more than 9,000 years old. A painting of a mammoth was found on the wall in 2007. Other artefacts from the site include an exquisitely carved mammoth ivory spearhead. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, February 16, 2011 |=|]

“Cheddar Man would have lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, making sharp blades from flints for butchering animals, using antlers to whittle harpoons for spear fishing and carving bows and arrows....Individuals inhabiting Gough’s Cave 5,000 years earlier... appear to have performed grisly cannibalistic rituals, including gnawing on human toes and fingers – possibly after boiling them – and drinking from polished skull cups. |=|

“The cave dwellers were among the first humans to return to Britain at the end of the last ice age. The island was unpopulated and almost completely under ice 20,000 years ago, but as the climate warmed, plants and animals moved across Doggerland, a now submerged land bridge that linked Britain to mainland Europe. Where food went, early humans followed and brought art, craft and toolmaking skills with them. |=|

“The ages of the remains at Gough Cave suggest it was home to humans for at least 100 years. The cave is well-sheltered and, with skin flaps over the entrance, would have made a cosy abode, Stringer said. The residents were ideally placed to hunt passing deer and wild boar, while up on the Mendip Hills roamed reindeer and horses. In the 1900s, several hundred tonnes of soil were removed from the cave to open it up as a tourist attraction, a move that may have destroyed priceless ancient remains. The skull cup and other bones unearthed in 1987 survived only because they were lodged behind a large rock.” |=|

13,000-Year-Old and 15,000-Year-Old Cultures in Switzerland

In 1998, construction workers excavating a parking lot in Chur, Switzerland, on the Rhine River near Liechtenstein, uncovered archaeological artifacts dating back to about 11,000 B.C. Chur is often described as “the oldest city in Switzerland.” If the artifacts are in fact evidence of a “village” or “city,” Chur would be 2,000 years older than Jericho. In Neuchâtel — at nearly the opposite, western end of Switzerland the country — archaeologists have found artifacts dating to about 13,000 B.C., some 2000 years older than those in Chur. [Source: Bill Harby, swissinfo, March 18, 2018 ***]

Switzerland is the home of other early historical milestones. Among the world's oldest examples of art are two Paleolithic harpoons, at least 60,000 years old, decorated with geometric figures discovered at Veyrier near Geneva. One of the oldest wheels ever found is a 4000-year old-wooden disc discovered at an archeological sight near Zurich. The wheel now can be seen in the Zurich Museum. Not many older wheels have been found. Wood usually rots to dust within a century or so, The Bernisches Historisches Museum is Bern houses a 4000-year-old ax with a jade blade and an antler socket and handle. The ax was made by people from the stick ax culture. The oldest known opium cultivators were the Neuchâtel shorline culture — people who lived around a Swiss lake in the forth millennium B.C. Traces of opium have been excavated from archeological sites there.

Alvastra pile dwelling

Bill Harby wrote in swissinfo, “It’s true that “Chur has certainly yielded some of the oldest archaeological finds in Switzerland”, says Professor Philippe Della Casa from the Institute for Archaeology at the University of Zurich. But they “belong to temporary camp sites, not to sedentary settlements”. To be called a “town”, certain criteria must be met, says Della Casa, including “centralized administration, complex planning and architecture, structured social organisation and specialised crafts”. By these criteria, “Chur is certainly not the ‘oldest town’ in Switzerland, since towns as such do not emerge before the Celtic Iron Age, the mid-first millennium B.C.”. ***

“Similarly, the earliest Neuchâtel shoreline artifacts are from “nomad camps of hunter-gatherers”, says Marc-Antoine Kaeser, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Neuchâtel and Director of Laténiumexternal link. Laténium is Switzerland’s largest archaeological museum. It stands by Lake Neuchâtel near where the oldest artifacts were found. In the archaeology park just outside the museum’s doors stand replicas of Neolithic lake dweller houses from 3810 B.C.. Inside, Laténium’s exhibits trace 500 centuries, beginning with the Neanderthals. ***

“Kaeser says the oldest permanent Neolithic settlements so far identified in Switzerland were in the Rhone valley and in the town of Bellinzona on the south side of the Alps. But “a real continuous occupation can only be attested from the Roman times on”. Professor Della Casa suggests we look to Zurich, Bern, Geneva or Baselexternal link as our oldest towns. “All these sites had fortified Celtic settlements in the second half of the first millenium B.C.,” he says. ***

“Thomas Reitmaier concurs with this timeline. Director of the Archaeological Service for canton Graubünden, Reitmaier’s office is in Chur. “This is quite tricky,” he says, but “generally the emergence of the earliest proto-urban and urban centres north of the Alps are dated to the first Millenium B.C.”. Therefore he adds it’s “difficult to determine the oldest Swiss town.” ***

What about Chur? “It seems clear: there are first late-Paleolithic Period (about 12,000 B.C.) remains of some camps, and some first settlements from the Neolithic Period (4,500 B.C.) onwards, till the Roman occupation and the founding of a rather small vicus [an ancient Roman settlement]”. But Reitmaier says “we should talk about the town of Chur from the medieval period at the earliest,” noting that the town walls weren’t constructed until the 13th century.

8,000-Year-Old Alpine Culture in the Alps

An international team of archaeologists led by experts from the University of York has uncovered evidence of human activity in the high slopes of the French Alps dating back over 8000 years. According to the University of York: “The 14-year study in the Parc National des Eìcrins in the southern Alps is one of the most detailed archaeological investigations carried out at high altitudes. It reveals a story of human occupation and activity in one of the world's most challenging environments from the Mesolithic to the Post-Medieval period. The work included the excavation of a series of stone animal enclosures and human dwellings considered some of most complex high altitude Bronze Age structures found anywhere in the Alps. The research, published in Quaternary International, was led by Dr Kevin Walsh, landscape archaeologist at the University of York in partnership with Florence Mocci of the Centre Camille Julian, CNRS, Aix-en-Provence. [Source: University of York, September 25, 2013]

“Dr Walsh explained: "High altitude landscapes of 2000 metres and above are considered remote and marginal. Many researchers had assumed that early societies showed little interest in these areas. This research shows that people, as well as climate, did have a role in shaping the Alpine landscape from as early as the Mesolithic period. "It has radically altered our understanding of activity in the sub-alpine and alpine zones. It is also of profound relevance for the broader understanding of human-environment interactions in ecologically sensitive environments." Excavations carried out by the team showed human activity shaped the Alpine landscape through the Bronze, Iron, Roman and Medieval ages as people progressed from hunting to more managed agricultural systems including the movement of livestock to seasonal alpine pastures, known as transhumant-pastoralism.

“"The most interesting period is the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age when human activity, particularly to support pastoralism, really begins to dominate the landscape," said Dr Walsh. "The Bronze Age buildings we studied revealed the clear development of seasonal pastoralism that appears to have been sustained over many centuries with new enclosures added and evidence of tree clearing to create new grazing land. "The evidence suggests the landscape was occupied over many centuries marking the start of a more sustained management of the alpine landscape and the development of the pastoral agricultural systems we see in the Alps today."

The study also uncovered evidence of Stone Age hunting camps in often inhospitable conditions in the upper reaches of the Alpine tree line at 2000 metres and above. Other finds included a Neolithic flint arrow head at 2475 metres, thought to be the highest altitude arrowhead discovered in the Alps.

The study was carried out by a team of British and French archaeologists and palaeoecologists. They surveyed over 300 sites across a number of valleys as well as studying pollen from cores taken from peat areas and lakes and carbonized wood remains Journal Reference: K. Walsh, M. Court-Picon, J.-L. de Beaulieu, F. Guiter, F. Mocci, S. Richer, R. Sinet, B. Talon, S. Tzortzis. A historical ecology of the Ecrins (Southern French Alps): Archaeology and palaeoecology of the Mesolithic to the Medieval period. Quaternary International, 2013; DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2013.08.060]

Mesolithic Alpine Crystal Hunters and Bronze Hand

According to Archaeology Magazine: In the winter of 2013, amateur geologist and expert crystal hunter Heinz Infanger was backcountry skiing in the mountains of central Switzerland’s canton of Uri when he came upon a rich vein of rock crystal exposed by a retreating glacier. Infanger soon discovered antler tools, wood fragments, and rock crystal artifacts, which suggested the outcropping had been visited by crystal hunters in the distant past. He reported his discovery to local heritage authorities, and a team led by archaeologist Marcel Cornelissen of the Institute of the Cultures of the Alps visited the site and conducted a thorough excavation. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

The team determined that hunter-gatherers living during the Alpine Mesolithic period (ca. 9000 — 5500 B.C.) visited the site as recently as 5900 B.C. and extracted rock crystal from the vein, after which it was covered by the advancing glacier. The closest known Mesolithic encampments are a two-day trek from the outcropping. Cornelissen and his colleagues have embarked on a broader field survey of the area, where warming conditions may have exposed more sites dating to this little-understood period.

Swiss archaeologists were baffled when they first saw the bronze hand wearing a gold foil bracelet. All the evidence — including radiocarbon dating of vegetable glue used to affix the gold foil and the style of a bronze dagger found along with the hand — suggests the unusual artifact was fashioned in the mid-second millennium B.C. But nothing like it is known from the period. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2019]

“At the site where the hand was found — a spectacular plateau in the shadow of the Alps and the Jura Mountains — archaeologists unearthed a man’s skeleton, along with a missing finger from the bronze hand as well as a bronze pin and spiral and several gold flakes. The hand’s purpose is enigmatic. “It may have been this man’s insignia,” says Andrea Schaer of the Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern, “and when he died it was buried with him.” She says the hand also may have served as a symbolic replacement for one perhaps lost by the man during his life, though it is too delicate to have been a practical prosthetic.

Mesolithic Palestine (12,000 to 10,000 B.C.)

Gerald A. Larue wrote: “Sometime between 14,000 and 12,000 years ago, the Mesolithic period or Middle Stone Age began in the Near East, and with it came a veritable social and technological revolution probably due, in part, to changes in climate at the close of the last Ice Age. The most dramatic evidence in Palestine has come from a site ten miles northwest of Jerusalem in the Wadi en-Natuf, which has given the name "Natufian" to the culture. In 1928, in a huge cave some 70 feet above the wadi, Miss Dorothy Garrod found evidence of a center of flint industry characterized by tiny crescents and triangles of flint known as micro-flints. [Source:Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Natufian sites, since found in other locations, suggest long periods of uninterrupted occupation and reveal a uniformity in art, industry, burial customs and artifacts that indicates close communication among groups, although it must be admitted that each site has its own distinctive features. Massive implements, such as huge basalt mortars weighing hundreds of pounds for grinding grain, were produced, as well as such delicate objects of bone as fish hooks, barbed harpoons and pins. A wide variety of tools, including adzes, sickles and picks, suggest the beginning of agriculture. Rock carvings portray men using lassoes and nets, and the imprint of matting on clay floors indicates the weaving of fibers.

“During this period the bow and arrow were used and, with better tools and weapons and having learned how to store food, it is possible that life became somewhat easier, providing time for artistic expression. Rock drawings and wall paintings depict men and animals with the precise pictorial representation so often characteristic of primitive art, but Natufian man moved beyond this phase into schematic and symbolic representation and geometric patterns. Skeletons were often decorated with necklaces, pendants, breast ornaments and headdresses of shell and bone. The curious custom of separating the skull from the rest of the skeleton has been variously interpreted as a cannibalistic rite, evidence of ancestor worship, a skull cult, or simply as an interesting hobby of collecting tokens of victory over enemies. Sea travel had begun, probably on rafts of bamboo or papyrus at first and later on more sophisticated ships, and the Near Eastern world was drawn more closely

See Separate Article: NATUFIANS (12,500-9500 B.C.): THE FIRST FARMERS? europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024