Home | Category: First Modern Human Life / First Modern Human Art and Culture

HOMES OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS

Modern humans generally didn't live in caves, it is thought, because they were too dark although cave mouths may have been used for shelter. Caves, some archaeologist contend, were used primarily for religious and artistic purposes.

There is evidence that around 400,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers, probably members of the species Homo heidelbergensis, constructed a camp with huts on a beach at Terra Amata, now a suburb of Nice, France. The largest hut was about 10 meters feet long, and consisted of an oval-shaped arrangement of saplings stuck in the ground, held up stones. Presumably on leaves or skins were placed to form a roof. A break in the ring show where a door of some sort must have been. Just inside here was a hearth. [Source: Ian Tattersall, Nautlius, December 5, 2013]

It has been theorized that modern human families lived in small settlements made up of moss-covered huts during the winter and carried reindeer skin tents with them when they followed game during the summers. Families may have slept under bearskin bedding and children may have been rocked to sleep in reindeer-skin cradles. Their equivalent of hot chocolate may have reindeer fat mixed with boiling water. [Source: John Pfieffer, Smithsonian magazine, October 1986]

A central platform at Star Carr, a 10,000-year-old site in North Yorkshire, England, was excavated by a research team studying past climate change events at the Middle Stone Age. Star Carr is home to the oldest evidence of carpentry in Europe and of built structures in Britain. [Source: Ashley Strickland, CNN, May 2, 2018]

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLIEST HOUSES, BUILDINGS AND WOODEN STRUCTURES factsanddetails.com;

NEANDERTHAL LIFE: CLOTHES, HOMES, LANGUAGE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HOMO ERECTUS LIFE, STRUCTURES, LANGUAGE, ART AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Paleolithic Revolution (The First Humans and Early Civilizations)” by Paula Johanson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Paleolithic Technologies (Routledge Studies in Archaeology)”

by Steven L. Kuhn Amazon.com;

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature” by Ludovic Slimak Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Human Culture”by Richard G. Klein (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Prehistory of the Mind: A Search for the Origins of Art, Religion and Science

by Prof Steven Mithen (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins” by Richard G. Klein Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow Amazon.com;

“Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind” by Colin Renfrew (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Culture: Based on an Interdisciplinary Symposium ‘The Nature of Culture’, Tübingen, Germany by Miriam N. Haidle (2016) Amazon.com;

“he Archaeology of Childhood: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on an Archaeological Enigma” by Güner Coşkunsu (2016) Amazon.com;

“Culture History and Convergent Evolution: Can We Detect Populations in Prehistory?

by Huw S. Groucutt (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sounds of Laughter, Shades of Life: Pleistocene to modern hominin occupations of the Bau de l'Aubesier rock shelter, Vaucluse, France” by Lucy Wilson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought”

by Pascal Boyer (2002) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age”

by Robert N. Bellah (2017) Amazon.com;

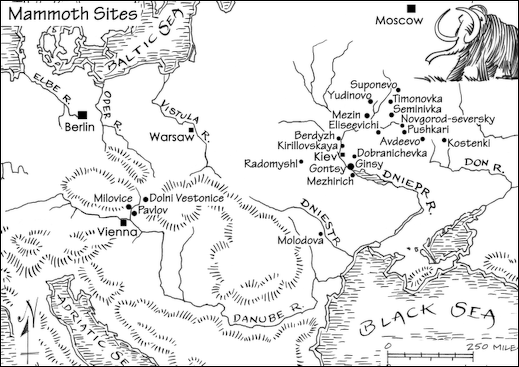

20,000-Year-Old, Mammoth-Bone Circles in Freezing Cold Russia

Around 70 mysterious bone circles have been built in Ukraine and the West Russian plain. The bones at one site indicate is is more than 20,000 years old. Yahoo News reported: “Researchers believe that ancient people built the circles with bones from animal graveyards, with 64 mammoth skulls used in the 9-x-9 meter (30-x-30 foot) structure, with other bones from animals including horses, bears wolves and arctic foxes. [Source: Rob Waugh, Yahoo News UK, March 18, 2020]

Archaeologists from the University of Exeter found for the first time the remains of charred wood and other soft non-woody plant remains within the circular structure, situated just outside the modern village of Kostenki, about 500 kilometers south of Moscow. This shows people were burning wood as well as bones for fuel, and the communities who lived there had learned where to forage for edible plants during the Ice Age.

“Dr Alexander Pryor, who led the study, said: "Kostenki 11 represents a rare example of Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers living on in this harsh environment. “What might have brought ancient hunter gatherers to this site?” “One possibility is that the mammoths and humans could have come to the area on masse because it had a natural spring that would have provided unfrozen liquid water throughout the winter — rare in this period of extreme cold.. These finds shed new light on the purpose of these mysterious sites. “Archaeology is showing us more about how our ancestors survived in this desperately cold and hostile environment at the climax of the last ice age. Most other places at similar latitudes in Europe had been abandoned by this time, but these groups had managed to adapt to find food, shelter and water."

The last ice age, which swept northern Europe between 75-18,000 years ago, reached its coldest and most severe stage at around 23-18,000 years ago, just as the site at Kostenki 11 was being built. Climate reconstructions indicate at the time summers were short and cool and winters were long and cold, with temperatures around -20 degrees Celsius or colder.

Abri Blanchard and Abri Castanet Rock Shelters in France

The Dordogne region of France is believed to have been inhabited by modern humans since 40,000 years ago. Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: “New York University archaeologist Randall White has spent many years here investigating two collapsed rock shelters once inhabited by some of Europe’s first modern humans.Abri Blanchard and its neighbor to the south,Abri Castanet, sit along a cliff face in the Castel Merle Valley, just beyond the quiet, 190-person commune of Sergeac.[Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

By carefully studying the microstratigraphy and composition of the limestone of the collapsed roof, White’s team estimates that Abri Castanet was about six-and-a-half feet high, 100-feet wide, and about 20 feet deep, with a ceiling reachable by Aurignacians standing on tiptoes, allowing them to modify it. Several blocks found at Abri Castanet during Peyrony’s excavations, as well as White’s, bear deep gouges in them that formed raised ring shapes known as anneaux. According to White, the anneaux appear both on blocks that would have been on the floor of the shelter and on parts of the collapsed roof. So far a total of 30 of them have been found on 18 different slabs. The working hypothesis is that they were used to string up reindeer hides, so that the Aurignacian people could close off the front of the shelters and effectively heat the space.

Abri Blanchard and Castanet once housed extended families who congregated possibly for the purpose of finding mates, group hunting, and other activities necessary for survival. At Abri Castanet, a steep slope covered by a pile of fallen rocks, soil, and debris extends to the top of the cliff. Immediately to the south is a vast clearing. White says that occupation might have extended south along the cliff face and deep into the clearing. White says, “This was Grand Central Station for reasons that are not very clear except for these deep rock shelters.”

“Forty thousand years ago, Europe was undergoing the so-called Middle Upper Paleolithic transition. As many as 5,000 years earlier, modern humans, or Homo sapiens, began to enter the continent from Africa. Other hominins, specifically Neanderthals, were already in Europe. Over the next 15,000 years, modern humans ventured further west onto the continent. Their encroachment scattered Neanderthals to the Iberian Peninsula in the west and into the Caucasus Mountains in the east. Neanderthals eventually died out roughly 30,000 years ago.

“There is no archaeological evidence pointing to any Neanderthal occupation in the rock shelters of Castel Merle Valley. Additionally, White and his colleagues hypothesize that there might have been only a relatively short window of time between formation of the rock shelters from climatic and geologic processes and their collapse. “White believes the area was a wide-open steppe with about 10 percent forest cover. The Vézère River is less than 200 yards away from the rock shelters and a freshwater spring still flows just in front of them. The average temperature in the region would have been anywhere from five to 20 degrees cooler than the roughly 50 degrees Fahrenheit it is today.

Mammoth Bone Huts and Skin Dwelling from 30,000 to 10,000 B.C.

Archaeological evidence from 30,000 to 10,000 B.C. shows that early homo sapiens built 40-foot-long and 12-foot-wide animal skin dwellings in southern Russia. Winter dwellings found in Czechoslovakia that back to 10,000 B.C. had round plans, animal-skin rugs, beds and hearths made with bones and animal dung.

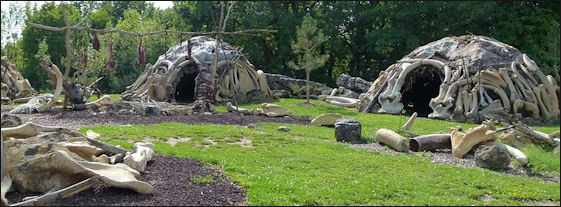

A 15,000-year-old modern human hut was excavated in the Ukraine southeast of Kiev at the junction of two Dnieper River tributaries. About eight feet high and the size of a small bedroom, it was held up with a retaining wall made of stacked mammoth bones. This is the oldest example of human's living in a shelter other than a cave. [Source: John Pfieffer, Smithsonian magazine, October 1986]

Four 15,000-year-old huts made from mammoth bones and tusks near the village Mezhirich in Ukraine were quite sophisticated. The walls were made of leg bones and skulls piled one another. The roof was made of tusks likely covered by hide. They contained the mandibles or more than a hundred mammoths, probably taken from a nearby mammoth "graveyard." Some have described them as proto yurts. Pits were dug in to the permafrost nearby may have been used to store frozen meat for a year-round meat supply. The site is viewed by some as an early village.

Mladec Caves, the World’s Oldest “Village”?

The Mladeč Caves is the Czech Republic is regarded by some as the world’s oldest “village.” Bones found there, dated to 31,000 years before present, are claimed to be the oldest human bones that clearly represent a human settlement in Europe. Located 10 kilometers from Hanácké Benátky, which is not far from the Morava river, the town of Litovel and the protected nature landscape area of Litovelské Pomoraví, the caves comprise a complex, multi-floor labyrinth of fissure passages, caves and domes inside the calcit hill Třesín. Some of the underground spaces are richly decorated. [Source: CzechTourism, Wikipedia]

The Mladeč Caves are located at an elevation of 343 meters (1,125 feet). The humans that lived there were early modern humans (Cro-Magnon) of the Upper Paleolithic period and Aurignacian culture. The site was discovered by Josef Szombathy and excavated in 1881-1882 and 1903-1922. It is currently managed by the Cave Administration of the Czech Republic Highlights include "Nature’s Temple" and the "Virgin Cave" but the caves associated with early humans are not open to the public.

The limestones in Mladeč Karst belong geologically to one of the belts of the Devonian rocks in the Central Moravian part of the Bohemian Massif (the Konice-Mladeč Devonian). The caves consist primarily of horizontal and very broken labyrinth of corridors, domes and high chimneys with remarkable modelling of walls and ceilings, and stalactites and stalagmites. There are numerous block cave-ins, with some steep corridors which extend even below the level of the underground water. +

replicas of mammoth bone huts

They archaeological remains found in Mladec caves represent the oldest, largest and most northern settlements yet found of early modern humans in Europe. These people lived here 31,000 years ago. The large number of bones from Stone Age human skeletons, Pleistocene vertebrates along with a large a number of fireplaces and stone instruments means that a fairly large number of people used the cave, making it an early settlement or “village.”

Szombathy recorded his visits and excavations to the cave in his diary, the sole source of information on the early excavations at the site. The first human fossil, the skull of Mladeč 1, was discovered during the first excavation in 1881. Other fossils discovered during this excavation include Mladeč 2, Mladeč 3, Mladeč 7, Mladeč 12-20 and Mladeč 27.] Mladeč 8, Mladeč 9 and Mladeč 10 were discovered during a second excavation in 1882. Later excavations revealed more human skulls and bones. In the early 20th century, large amounts of sediment were removed from the caves without the guidance of archaeologists, destroying a great deal of valuable potential information on the cave. Many of the discoveries at Mladeč have been lost or destroyed over time, due to unauthorized looting and excavations, disappearances into private collections, and the large destruction of artefacts stored at Mikulov Castle, which was set on fire by the Germans at the end of World War II.[9] Ironically, the anthropological collection from the Moravské zemské muzeum, which included a large collection of fossil artefacts from Mladeč, had been moved to Mikulov Castle during the war for safekeeping purposes. Out of the 60 human fossils from Mladeč stored at Mikulov Castle, only 5 could be recovered following the fire. +

Artifacts Found at the Mladec Caves

Forty bone points have been discovered at Mladec Caves but only a few stone artefacts were found. The bone points at Mladeč have been found at other Central European sites in an Aurignacian context. None of the bone points from Mladeč have a split base. Rather they have a massive base. These artefacts are referred to as Mladeč-type bone points or bone projectiles. When found at other sites with split base bone points occurring in a separate layer, the layer with Mladeč-type bone points is always found above the layer with split base bone points. The Mladeč-type bone points appear in an Aurignacian context after 40,000 years ago. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Other artefacts include 22 perforated mammalian teeth, likely used as pendants. Perforated animal teeth used as pendants are frequently found at Aurignacian sites. The perforated teeth from Mladeč came from wolves, bears, and uncommonly, beavers and moose. The few stone tools can clearly be ascribed as Aurignacian. The remains of carbonized rope were discovered in 1882 by Szombathy. In 1981, archaeologists discovered ochre-colored marks on some of the walls at Mladeč. A total of 632 bones from large mammals have been discovered at Mladeč. These come primarily from bovids (primarily steppe bison, but a few from aurochs), bears (primarily Ursus deningeri, but a few from Ursus spelaeus), reindeer, horses and wolves. +

More than 100 human fossil fragments were discovered at Mladeč. Researchers failed to extract usable DNA from the Mladeč human fossils for the purposes of aDNA analysis. However, two (out of twelve) of the Mladeč specimens, Mladeč 2 and Mladeč 25c, yielded a limited amount of mtDNA, which did not contain Neanderthal mtDNA sequences. Direct AMS dating of the human fossils from Mladeč yielded uncalibrated dates of around 31,190 years ago for Mladeč 1, 31,320 years ago for Mladeč 2, 30,680 years ago for Mladeč 8 and 26,330 years ago for Mladeč 25c.

Dolní Vestonice and Other Mammoth Age sites

Dolní Vestonice

Dolní Věstonice is another candidate for the world’s oldest “village” based on its age and the large amount artisanship and activity that went on there. An Upper Paleolithic archaeological site near the village of Dolní Věstonice, Moravia in the Czech Republic,on the base of 549-meter-high Děvín Mountain, it thrived 26,000 years ago based on radiocarbon dating of objects and remains found there. The site is unique and special because of the large number of prehistoric artifacts (especially art), dating from the Gravettian period (roughly 27,000 to 20,000 B.C.) Found there. The artifacts include includes carved representations of men, women, and animals, along with personal ornaments, human burials and enigmatic engravings. [Source: Wikipedia]

Most scholars argue that Dolni Vestonice is too small and too rudimentary to qualify as a village or town. It and nearby Pavlov are regarded as hill sites and the home of prehistoric seasonal camps. In any case a number of important discoveries related to early man have been found there.

The stone-age men at Dolni Vestonice and Pavlov sites in the Czech Republic had textiles, ceramics, cords, mats, and baskets. Evidence of these things are impressions left on clay chips recovered from clay floors hardened by a fire. The impressions of textiles indicate that these people may have made wall hangings, cloth, bags, blankets, mats, rugs and other similar items.

Ancient men at Dolni Vestonice and Pavlov in the Czech republic ate a lot of meat. They cooked stews and gruel in pits lined with hide and heated with hot rocks. In October 2004, team of European and Israeli archaeologists announced unearthed the oldest known clay fireplaces made by humans at a dig in southern Greece have. The hearths, excavated from the Klisoura Cave, in the northwest Peloponnesus, are at least 23,000 to 34,000 years old and were probably used for cooking by prehistoric residents of the area, according to the archaeology journal Antiquity. The study said that remnants of wood ash and plant cells had also been found in the hearths. The discovery, experts say, helps explain the transition from the oldest known hearths, made of stone, to clay structures like the ones at Dolni Vestonice in the Czech Republic. [Source: Anthee Carassava, New York Times]

Humans of the of the Upper Pleistocene have been characterized mammoths hunters who used spears. Indentations of netting on the clay floors of the huts at Dolni Vestinice strongly suggest the people there were using nets to catch smaller prey. The discovery of shells at the site that originated from the Mediterranean suggests people traveled far to collect them or traded goods with other groups.

Dolni Vestonice Artworks and Ceramics

Some of earliest known ceramics were found at Dolni Vestonice and Pavlove. Thousands of fragments of human figures, as well as the kilns that produced them have been found in sites in Slovakia, Russia and the Czech Republic. Some have been dated to be 26,000 years old. The figurines were made from moistened loess, a fine sediment, and fired at high temperatures. Predating the first known ceramic vessels by 10,000 years, the figurines, some scientists believe, were produced and exploded on purpose based on the fact that most of the sculptures have been found in pieces.

Thousands of ceramic artifacts, many of them animals, have been found at site. The animals molded in the clay include lions, rhinoceroses, and mammoths. They have been interpreted to have been of some ceremonial significance. Two figurines depicting women were found. One of the figurines, known as the Black Venus, was found on a hillside amongst charred mammoth bones; the other depicted a woman with a deformed face. The remains of some of the clay animals were stabbed as if hunted. Other pieces of blackened pottery still bear the fingerprints of the potter.

Dolni Vestonice is the site of the earliest known potter’s kiln. Carved and molded images of animals, women, strange engravings, personal ornaments, and decorated graves have been found scattered over several acres at the site. In the main hut, where the people ate and slept, two items were found: a goddess figurine made of fired clay and a small and cautiously carved portrait made from mammoth ivory of a woman whose face was drooped on one side. The goddess figurine is the oldest known baked clay figurine. On top of its head are holes which may have held grasses or herbs. The potter scratched two slits that stretched from the eyes to the chest which were thought to be the life-giving tears of the mother goddess. [Source: mnsu.edu/emuseum/archaeology/sites/europe/dolni_vestonice]

Some of the sculpture may represent the first example of portraiture (representation of an actual person). One such figure, carved in mammoth ivory, is roughly three inches high. The subject appears to be a young man with heavy bone structure, thick, long hair reaching past his shoulders, and possibly the traces of a beard. Particle spectrometry analysis dated it to be around 29,000 years old. [Source: Wikipedia]

female figurines from Dolni Vestonice

Buildings and Burials at Dolni Vestonice

Dolni Vestonice was located along a stream in a swampy area at the confluence of two rivers near the Moravian mountains near present-day the village of Dolni Vestonice. Its people saved the bones of the mammoths and other animals they hunted and and herded and used them to construct a fence-like boundary. The perimeter of the site was easy to distinguish. At the center of the enclosure was a large bonfire. Huts were grouped together within the bone fence. [Source: Wikipedia]

At an isolated site 80 meters upstream was a lean-to shelter dug into an embankment. The remains of a kiln was found inside. The door of the small hut faced towards the east. Scattered around the oven were many fragments of fired clay. An estimated 2,300 clay figurines of various animals were found in and around the remains of a kiln there.

In 1986, the remains of three teenagers were discovered in a common grave dated to be around 27,650 years old. Two of the skeletons belonged to heavily built males while the third was judged to be a female based on its slender proportions. Archaeologists who examined her skeletal remains found evidence of a stroke or other illness which left her painfully crippled and her face deformed. The two males had died healthy, but remains of a thick wooden pole thrust through the hip of one of them suggests a violent death.

A woman’s skeleton was found buried under the scapula of a mammoth, with a fox pelt and red ochre. Such a burial is believed to have been reserved by people of high status. The female skeleton was ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. The bones and the earth surrounding it contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull and one hand held the body of a fox. Some see this as evidence indicates that it was the burial site of a shaman. If so it would be the oldest evidence of a female shaman.

200,000 and 77,000 Year-Old Beds Found in South Africa

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: The people living in South Africa’s Border Cave up to 200,000 years ago knew how to make a cozy home. Excavations that took place between 2015 and 2019 have revealed that the cave’s residents slept on bedding that was made by piling broad-leafed grass on top of a layer of ash from the many fireplaces within the cave. The ash may have kept crawling insects from disturbing sleepers, says Lyn Wadley of the University of the Witwatersrand. Wadley believes that this type of bedding was very common in the distant past, but that it rarely survives in the archaeological record. The research team removed layers of the cave’s sediment in blocks and excavated them in the lab, which enabled them to examine their contents under a microscope. This meticulous approach revealed tiny pieces of ash and plant fibers that made up the bedding used by the cave dwellers between 200,000 and 35,000 years ago. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

In 2011 scientists announced that they had discovered sleeping mats made that were about 77,000 years old in a South African cave. “Microscopic analysis of the bedding suggested the inhabitants repeatedly refurbished the mats. Starting about 73,000 years ago, the site's inhabitants apparently also burned the bedding regularly, "possibly as a way to remove pests," said researcher Christopher Miller, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany. Miller said. "This would have prepared the site for future occupation and represents a novel use of fire for the maintenance of an occupation site." These mats were used for more than just slumber. "The bedding was not just used for sleeping, but would have provided a comfortable surface for living and working," researcher Lyn Wadley, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, said. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, December 8, 2011]

“Beginning about 58,000 years ago, the layers of bedding at the site became more densely packed, and the number of hearths and ash dumps rose dramatically as well. The archaeologists believe this is evidence of a growing population, perhaps corresponding with other population changes within Africa at the time. By approximately 50,000 years ago, modern humans began expanding out of Africa, eventually replacing now-extinct forms of humans in Eurasia, including the Neanderthals.

“The age of the oldest mats are roughly contemporaneous with other South African evidence of modern human behavior, such as the use of perforated shell beads, sharpened bone points likely used for hunting, bow and arrow technology, the use of snares and traps and the production of glue for attaching handles onto stone tools. "These discoveries show the creativity and diversity of behavior that these early humans practiced," Miller told LiveScience.

77,000 Year-Old Bedding from South Africa Repelled Insects

In 2011 scientists announced that they had discovered the oldest known bedding made of mosquito-repellant evergreens (about 77,000 years old) in a South African cave. The use of medicinal plants in this way, together with other artifacts at the cave, showed how clever our human ancestors could be, the scientists said. The findings were detailed in the December 9, 2011 issue of the journal Science. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, December 8, 2011]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: “ An international team of archaeologists discovered the stack of ancient beds at Sibudu, a cave in a sandstone cliff in South Africa. They consist of compacted stems and leaves of sedges, rushes and grasses stacked in at least 15 layers within a chunk of sediment 10 feet (3 meters) thick."The inhabitants would have collected the sedges and rushes from along the uThongathi River, located directly below the site, and laid the plants on the floor of the shelter," said researcher Lyn Wadley, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. The oldest mats the scientists discovered are approximately 50,000 years older than other known examples of plant bedding. All told, these layers reveal mat-making over a period of about 40,000 years. "The preservation of material at Sibudu is really exceptional," said Miller.

“Many of the plant remains are species of Cryptocarya, evergreen plants that are used extensively in traditional medicines. The beds appeared to be mostly composed of river wild-quince (Cryptocarya woodii), whose crushed leaves emit insect-repelling scents. "The selection of these leaves for the construction of bedding suggests that the early inhabitants of Sibudu had an intimate knowledge of the plants surrounding the shelter, and were aware of their medicinal uses," Wadley said. "Herbal medicines would have provided advantages for human health, and the use of insect-repelling plants adds a new dimension to our understanding of behavior 77,000 years ago."

Massive 25,000-Year-Old Ice Box in Russia

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: When a circular structure measuring more than 13 meters (40 feet) in diameter, made entirely from mammoth bones, was discovered in western Russia in 2014, its purpose was unclear. Now, researchers have investigated debris from the site of Kostenki, which is located along the Don River just south of the Russian city of Voronezh and was inhabited by hunter-gatherers some 25,000 years ago. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2020]

By separating possible evidence of human habitation, such as charcoal produced by fires, from sediment, they determined that the structure was likely not used for shelter. “The density of this debris was far less than we’d expect to see if it was an intensively occupied dwelling,” says archaeologist Alexander Pryor of the University of Exeter. It would have been difficult to build a roof on such a large structure, he adds. Furthermore, many of the bones used to build it appear to have had fat and cartilage still attached to them, which would have created a smelly, unhygienic environment. Instead, Pryor suggests, the structure may have been used to store food, possibly allowing the community to eat well while remaining at the site for weeks or even months at a time.

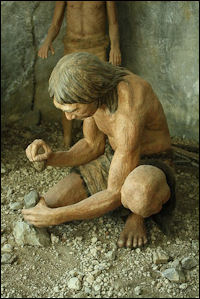

Fire and Debate about Which Hominins First Started Cooking

L.V. Anderson wrote on Slate.com: According to Harvard primatologist Richard Wrangham, “H. erectus must have had fire—just look at their anatomy! H. erectus had smaller jaws and teeth (and smaller faces in general), shorter intestinal tracts, and larger brains than even earlier hominins, such as Australopithecus afarensis, for instance, who were boxier, more apelike, and probably duller. Wrangham argues that H. erectus would not have developed its distinctive traits if the species hadn’t been regularly eating softer, cooked food. [Source: L.V. Anderson, Slate.com, October 5, 2012 \~/]

“If H. erectus didn’t bring fire mastery to Europe, who did? Archaeologists Wil Roebroeks of Leiden University in the Netherlands and Paola Villa of the University of Colorado Museum found evidence for frequent use of fire by European Neanderthals between 400,000 and 300,000 years ago. Roebroeks and Villa looked at all the data collected at European sites once inhabited by hominins and found no evidence of fire before about 400,000 years ago—but plenty after that threshold. Evidence from Israeli sites put fire mastery at about the same time. H. sapiens arrived on the scene in the Middle East and Europe 100,000 years ago, but our species didn’t have a discernible impact on the charcoal record. Roebroeks and Villa conclude that Neanderthals must have been the ones who mastered fire. \~/

“One of the beautiful things about the archaeological record is that archaeologists are always willing to debate about it. Attributing fire to Neanderthals is an overly confident reading of the evidence, according to archaeologist Dennis Sandgathe of British Columbia’s Simon Fraser University. Of course the number of campsites with evidence of fire increased between 1 million and 400,000 years ago, he says—the number of campsites, period, increased during this time in proportion with population growth. But that doesn’t mean the use of fire was universal among European hominins—there are plenty of Neanderthal campsites out there that show little or no evidence of fire, and Sandgathe has personally excavated some of them. What’s more, Sandgathe told me when I asked him about Roebroeks’ and Villa’s data, “We actually have better data than they do when it comes to Neanderthal use of fire.” \~/

“According to Sandgathe and his colleagues, hominins didn’t really master fire until around 12,000 years ago—well after Neanderthals had disappeared from the face of the planet (or merged into the human gene pool via interbreeding, depending on your view). Sandgathe and his colleagues excavated two Neanderthal cave sites in France and found, surprisingly, that the sites’ inhabitants used hearths more during warm periods and less during cold periods. Why on earth would Neanderthals not build fires when it was freezing outside? In “On the Role of Fire in Neandertal Adaptations in Western Europe: Evidence from Pech de l’Aze´ IV and Roc de Marsal, France,” Sandgathe advances the hypothesis that European Neanderthals simply didn’t know how to make fire. All they could do was harvest natural fires—those caused by lightning, for instance—to occasionally warm their bodies and cook their food. (This explains why Sandgathe found more evidence of fire from warm periods: Lightning is far less common during cold spells.) \~/

“Roebroeks and Villa think Sandgathe’s reasoning is flawed: After all, there isn’t evidence of fire at every modern human campsite, either, when you look at sites from the Upper Paleolithic period, which concluded about 10,000 years ago. “However, nobody would argue that Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers were not habitual users of fire,” they wrote in a response to Sandgathe et al.’s criticism of their work. Wrangham, meanwhile, thinks both Sandgathe et al. and Roebroeks et al. ignore some critical nonarchaeological evidence: his point that contemporary humans can’t survive on a diet of uncooked food. Accepting Sandgathe’s hypothesis, Wrangham wrote in an email, “means that the contemporary evidence is wrong, or that humans have adapted to need cooked food only in the last 12,000 years. Both suggestions are very challenging!” \~/

DNA Adaptation Helped Early Humans Deal with Toxic Fumes

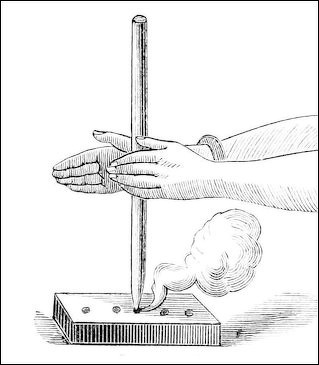

Ancient fire-making method

In a study published in Molecular Biology and Evolution in 2016 scientists said early humans may have developed a genetic mutation that shielded them from the harmful cancer-causing hydrocarbons fume from campfire smoke and this gave them an advantage over Neanderthals. Naomi Stewart wrote in The Guardian: “Researchers at Pennsylvania State University looked at what is called the aryl hydrocarbon receptor gene which plays a role in the breakdown of certain noxious substances. When organic matter such as meat or wood is burned it releases polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which can mutate DNA and cause cancer, as the World Health Organisation cautioned against in 2015. The PAHs are absorbed when we eat grilled meats or breathe in smoke. Once inside the body, their presence triggers aryl hydrocarbon receptors into producing enzymes that break them down so they can be flushed out. [Source: Naomi Stewart, The Guardian, August 2, 2016]

“But according to the research’s author Gary Perdew , when we breathe in too many toxic substances, just as we would in smoky caves, enzyme production goes into overdrive. The extra enzymes create a slew of toxic by-products that Perdew describes as “uber-toxicity”. The mutation Perdew and his team identified appears to slow down enzyme production to a rate that limits the risk of this toxicity. They theorise this may have made humans less sensitive to smoke’s harmful effects, allowing them to be around fires more often and offered an evolutionary advantage. Neanderthals, who appear to lack the mutation, would have struggled with more smoke-related respiratory infections, fertility problems, and mortality. “We prospered because of this mutation,” Perdew said. “I wouldn’t say Neanderthals died out because of it, but it could have been a contributing factor.” |=|

“The forerunner of modern humans and Neanderthals, Homo erectus, learned to control fire for warmth and cooking at least 1.9 million years ago in Africa. Both picked up the practice from this common ancestor, but with fire came greater exposure to smoke in enclosed caves. “They weren’t the greatest cooks,” said Perdew. “And it wasn’t easy to start a fire, so they might have kept a little fire burning all the time. They were probably burning grasses, whatever they could get their hands on.” |=|

“The scientists studied the gene in nine modern humans, including one from 45,000 years ago, three Neanderthals, and one member of the related but mysterious Denisovans in Siberia. The mutation was not present in the Neanderthals or Denisovan, but it was found in all of the modern humans. If the claims hold up it would be one of the first examples of human evolution in response to environmental pollution. However, given the small sample size of Neanderthals and the threadbare fragments of their DNA, the hypothesis is still tentative. |=|

“David Wright, an archaeologist at Seoul National University and the University of York, was cautious about the interpretation, and said that historical evidence does not seem to line up with the theory. “Neanderthals were the ultimate cave-dwelling fire users. If there was some selective disadvantage against this, then they would have died out a long time before they did. But they were actually one of the more successful stories in human evolution and lasted a really long time compared to other hominins,” he said. “That somehow Homo erectus and Neanderthals and dozens of other hominin species couldn’t handle sitting around a fire, it doesn’t make any sense to me,” he added. “The problem is it’s really difficult to test, because we can’t take a Neanderthal and sit them next to a fire to see how they react.” |=|

“Emily Monosson, an environmental toxicologist at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst said: “It wouldn’t be unexpected that being exposed to a contaminant that makes you sick would be a selective pressure on humans.” However, she agreed with being cautious: “You’re talking about one helpful adaptation against one chemical, but there’s a lot of other harmful particulates in smoke.” |=|

Lamps, Boats and Early Modern Human Possessions

Ancient men at the 24,000-year-old Dolni Vestonice and Pavlov sites in the Czech Republic had textiles, ceramics, cords, mats, and baskets. Evidence of these things are impressions left on clay chips recovered from clay floor that was hardened by a fire. The impressions of textiles indicate that these people may have made wall hangings, cloth, bags, blankets, mats, rugs and other similar items. Small items tha have been recovered from modern humans sites include drilled animals teeth, cloak pins and horse figurines.

In October 2004, team of European and Israeli archaeologists announced unearthed the oldest known clay fireplaces made by humans at a dig in southern Greece have. The hearths, excavated from the Klisoura Cave, in the northwest Peloponnesus, are at least 23,000 to 34,000 years old and were probably used for cooking by prehistoric residents of the area, according to the archaeology journal Antiquity. The study said that remnants of wood ash and plant cells had also been found in the hearths. The discovery, experts say, helps explain the transition from the oldest known hearths, made of stone, to clay structures like the ones at Dolni Vestonice in the Czech Republic. [Source: Anthee Carassava, New York Times]

No boats or rafts from the period when people arrived in Australia — around 60,000 years ago — have been found. Remains of boats found in Australia, Sardinia and Crete show that men have been crossing seas for more than 10,000 years. The oldest known boat is a dugout found in Denmark dated to 6000 B.C. The oldest known vessels with planks were found in Egypt and date to about 3000 B.C.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Blombos Cave objects from Blombos Cave website

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated May 2024