Home | Category: Neanderthals, Denisovans and Modern Humans / Neanderthals, Denisovans and Modern Human

DENISOVANS, MODERN HUMANS AND NEANDERTHALS

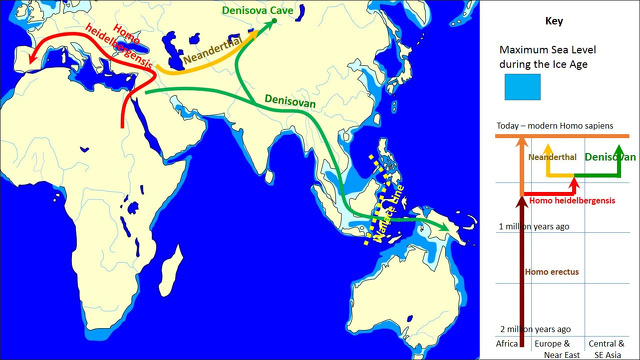

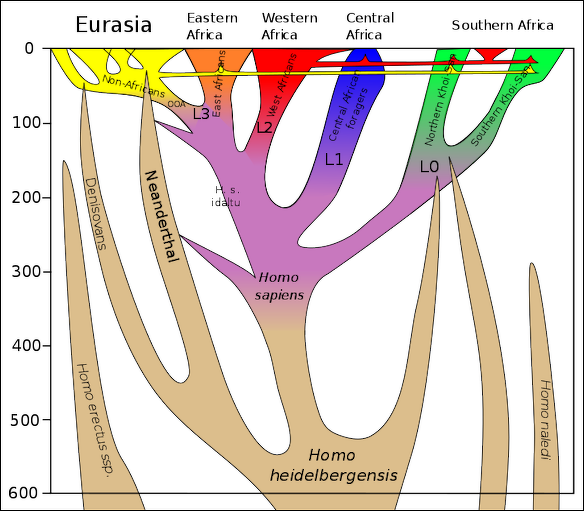

secondary human expansion

Genome studies have shown that our species, Homo sapiens, interbred with Denisovans as recently as 30,000 years ago. As a result, some modern people share about 5 percent of their DNA with Denisovans including indigenous populations in Papua New Guinea, Australia and the Philippines, with smaller DNA percentages among the broader Southeast Asian populations.

Denisovans are an extinct group of hominins who coexisted with the Neanderthals and modern humans around 30,000 to 50,000 years ago and originated at least 200,000 years ago. Not much is known about them other than what can be gleaned from their DNA and a few rare fossils. Scientists first learned of their existence from an incomplete finger bone and two molars discovered in the Denisova Cave in the the Altai region — where Kazakhstan, Mongolia, China and Russia all come together.

The existence of Denisovans was unknown until the tip of a finger bone about 40,000 years old was found in 2010. Three molars have been found at that site. A partial Denisovan jawbone from about 160,000 years ago subsequently was discovered in a Tibetan cave. A Denisovan tooth was later found in Laos [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, May 18, 2022]

RELATED ARTICLES: DENISOVANS: CHARACTERISTICS, DISCOVERY AND DNA europe.factsanddetails.com ; WHERE DENISOVANS LIVED europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Secret World of Denisovans: The Epic Story of the Ancient Cousins to Sapiens and Neanderthals” by Silvana Condemi and François Savatier (2025) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Investigations: From Denisovans to Neanderthals; DNA to stable isotopes; hunter-gathers to farmers; stone knapping to metallurgy; cave art .by Christopher Seddon Amazon.com;

“In search of Homo heidelbergensis: How Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and hobbits emerged" by Christopher Seddon Amazon.com;

“The World Before Us: How Science is Revealing a New Story of Our Human Origins”

By Tom Higham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Them and Us: How Neanderthal Predation Created Modern Humans” by Danny Vendramini (2014) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala and Camilo J. Cela-Conde (2017) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

Denisovan, Modern Human and Neanderthal DNA Analysis

DNA Research has indicated that Denisovans, Neanderthals and modern humans interbred. Scientists believe that interbreeding with the Denisovans contributed to the development of the modern human immune system and possibly made humans living today susceptible to allergies.

According to DNA taken from a 50,000-year-old a fossilized Neanderthal toe bone found in a Siberian Cave: 2 percent of the DNA of modern people not of African descent came from Neanderthals and 0.5 percent of Denisovan DNA came from Neanderthals, and that an estimated 0.2 percent of the DNA of mainland Asians and Native Americans comes from Denisovans. [Source: Monte Morin, Los Angeles Times, December 18, 2013 \=]

Marlowe Hood of AFP wrote: “Among the genetic legacy of Denisovans to some modern humans is a variant of the gene EPAS1 that makes it easier for the body to access oxygen by regulating the production of haemoglobin, according to a 2014 study. Nearly 90 percent of Tibetans have this precious variant, compared with only nine percent of Han Chinese, the dominant — and predominantly lowland — ethnic group in China.” [Source: Marlowe Hood, AFP, August 23, 2018 \=/]

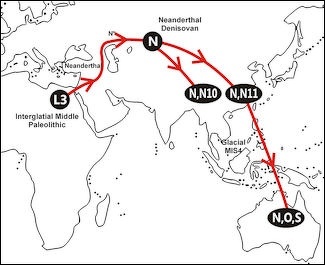

Global Distribution of Denisovan Genes

Genetic analysis suggests the ancestors of modern humans interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans. Neanderthal DNA makes up 1 to 4 percent of modern Eurasian genomes, Denisovans are most closely related to one group of living humans – the Melanesians of southeast Asia and their Australian neighbours. These groups carry Denisovan DNA from interbreeding event that must have happened as their ancestors passed through southern Asia over 40,000 years ago. and Denisovan DNA makes up 4 to 6 percent of modern New Guinean and Bougainville Islander genomes in the Melanesian islands.

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology: “A new technique for sequencing ancient DNA has allowed a multinational research team to reconstruct the genome of a person who lived in Siberia’s Denisova Cave between 30,000 and 82,000 years ago—with the same level of accuracy as genomes from modern people. This new DNA sequence gives researchers a clearer picture of how early hominins such as the Denisovans and Neanderthals were related to modern humans and to each other. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology, December 17, 2012]

The analysis showed that Denisovans were much more closely related to Neanderthals than to Homo sapiens, and that in spite of coming from a small population, they managed to contribute genes to modern populations in Island Southeast Asia and Australia. According to David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and a member of the research team, the new DNA sequence also shows that Native Americans and people from East Asia have more Neanderthal DNA, on average, than Europeans. Archaeologists have long thought that the largest population of Neanderthals lived in Europe, so the finding complicates the picture of the way modern people and Neanderthals are related. Either there was a separate event in which Neanderthals interbred with people in Asia, or the genetic contribution of Neanderthals in Europe was diluted by later migrations of Homo sapiens.

DNA from Neanderthal Toe Reveals Interbreeding with Humans and Denisovans

secondary human expansion

A 50,000-year-old toe bone from a Neanderthal, discovered in Denisova Cave in Siberia, gave up DNA indicating interbreeding between Neanderthals, modern humans and Denisovans scientists reported in the journal Nature. DNA from the Neanderthal toe fossil was compared to the genomes of 25 present-day human and a group of Denisovans. According to their analysis, Neanderthals contributed roughly 2 percent of their DNA to modern people outside Africa and half a percent to Denisovans, who contributed 0.2 percent of their DNA to Asian and Native American people.[Source: Monte Morin, Los Angeles Times, December 18, 2013 \=]

Monte Morin wrote in the Los Angeles Time: “The biggest surprise, though, was the finding that a fourth hominin contributed roughly 6 percent of the DNA in the Denisovan genome. The identity of this DNA donor remains a mystery. “It is possible that this unknown hominin was what is known from the fossil record as Homo erectus,” said lead study author Kay Prufer, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. “Further studies are necessary to support or reject this possibility.” \=\

“Geneticists and anthropologists said the inch-long bone and resulting analysis have greatly illuminated a period of time roughly 12,000 to 126,000 years ago. It does seem that Eurasia during the Late Pleistocene was an interesting place to be a hominin, with individuals of at least four quite diverged groups living, meeting and occasionally having sex,” biologist Ewan Birney of the European Bioinformatics Institute and Stanford geneticist Jonathan Pritchard wrote in a commentary that accompanied the study. \=\

“The toe bone was discovered in an ancient natural shelter called Denisova Cave, in Siberia’s Altai Mountains. It was in the same cave that archaeologists discovered evidence of the Denisovans, who were recognized as a distinct group in 2010. Based on DNA taken from the toe bone, researchers were able to determine that it belonged to a female Neanderthal. They could also tell that her parents were very closely related, and “were either half siblings who had a mother in common, double first cousins, an uncle and a niece, an aunt and a nephew, a grandfather and a granddaughter, or a grandmother and a grandson,” they wrote in the study.

“Such inbreeding might have been necessary because the Neanderthal population was very small, perhaps already well on the road toward extinction, the study authors suggested. “The data are consistent with the population being small enough that breeding among relatives was reasonably common,” said UC Berkeley biologist Montgomery Slatkin, a member of the research team. DNA analysis of additional Neanderthal remains would be needed to confirm that hunch, Slatkin said.

“The study authors estimated that the ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans split from the lineage that led to modern humans roughly 600,000 years ago, and then split between each other roughly 400,000 years ago. Based on the genomes of each group, researchers concluded that all of their populations were in decline at least 1 million years ago. Sometime after that, our ancestors began to grow in number while the Neanderthal and Denisovan populations continued to shrink. Researchers estimate that Homo sapiens became the planet’s sole surviving humans roughly 30,000 years ago.

While the study’s conclusions were sure to fire the imagination of the general public, at least one outside expert said the anthropological sleuthing had just begun. John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said it was very difficult to pin down the timing and number of groups involved in genetic mixing. We could really be looking at mixture from multiple different populations with different histories,” Hawks said.

Study authors hope that by mapping the Neanderthal genome they might gain insights into the evolution of modern humans. The list of DNA sequences that distinguish us from Neanderthals is relatively short, according to the study’s senior author, Svante Paabo, director of the Max Planck Institute’s department of genetics. It’s a catalog of the genetic features that sets all modern humans apart from all other organisms living or extinct,” Paabo wrote in a statement released by the institute. “I believe that in it hide some of the things that made the enormous expansion of human populations and human culture and technology in the last 100,000 years possible.”

Denisova cave artifacts

Humans Bred with Denisovans More than Once, Study Shows

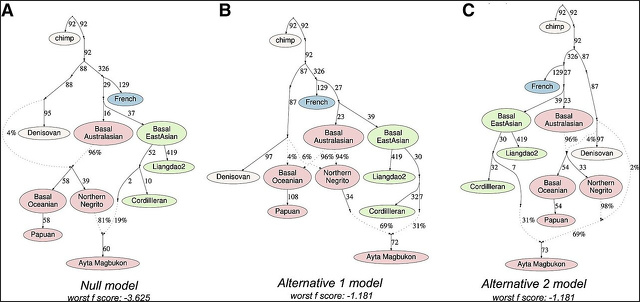

A study published in the journal Cell in March 2018, shows modern humans appear to have mated with Denisovans in Siberia and a separate group of Denisovans as they traveled across South Asia “This is a breakthrough paper,” said David Reich, the Harvard University geneticist who was not involved with the study. “It’s a definite third interbreeding event,” one that adds to the previously known Denisovan and Neanderthal mixtures. [Source: Ben Guarino, Washington Post, March 16, 2018 ^||^] Ben Guarino wrote in the Washington Post: “A team of scientists, led by University of Washington biostatistician Sharon Browning, took an approach that Reich called a “technical tour de force.” In the new study, Browning and her colleagues examined more than 5,500 genomes of modern humans from Europe, Asia and Oceania, looking for any possible archaic DNA. “We’re looking for segments of DNA in an individual that look quite different from the rest of the variation in the population,” Browning said. ^||^

“After the team fished out the DNA variations, the researchers matched the segments to Denisovan and Neanderthal sequences, known from samples in Siberia’s Altai Mountains. All groups studied, from British and Bengali people to Peruvians and Puerto Ricans, had a dense cluster that closely matched the Altai Neanderthals. Some populations also had a cluster that matched the Altai Denisovans, which was particularly pronounced in East Asians. The surprise was a third cluster – not like the Neanderthal DNA and only partially resembling the Altai Denisovans. ^||^

“This, the authors concluded, was a second and separate pulse of Denisovan genes into the DNA blender. “The geography is quite suggestive,” Browning said. The authors hypothesize that, as ancestral humans migrated eastward, they came across two different Denisovan populations. One pulse, to the north, shows up in people from China, Japan and Vietnam. The other Denisovan pulse appears to the south. “Maybe it was down in the southeast corner of Asia,” Browning said. “It could possibly have been on an island en route to Papua New Guinea, but we clearly don’t know.” ^||^

“Reich said he would not be surprised if methods similar to this one revealed additional mixtures. “I am sure there are others,” he said, considering the wide range of archaic groups across Eurasia. Browning plans to continue to hunt for additional mixtures, including among people of African descent who were excluded from this study because the warm continental climate makes finding archaic DNA a challenge. “We’re interested in other populations around the world, especially Africa,” she said.” |=|

Denny, the Neanderthal-Denisovan Love Child

Denny was an inter-species love child, with a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father, scientists reported in the journal Nature. Nicknamed by Oxford University scientists, Denisova 11 — her official name — was at least 13 when she died, for reasons unknown. "There was earlier evidence of interbreeding between different hominin, or early human, groups," said lead author Vivian Slon, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. "But this is the first time that we have found a direct, first-generation offspring," she told AFP. [Source: Marlowe Hood, AFP, August 23, 2018 \=/]

Lydia Pyne wrote in Archaeology magazine: Genetic testing of a single, 90,000-year-old sliver of bone from an approximately 13-year-old girl has confirmed something researchers had long suspected: It has provided clear evidence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and Denisovans. Earlier analysis of the girl’s mitochondrial DNA had shown that her mother was of Neanderthal ancestry. Later research examined her entire genome. They then compared it to previously sequenced paleogenomes, including those of other ancient humans. The results were unambiguous — the girl’s DNA matched Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes to an equal degree. She had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. [Source: Lydia Pyne, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2019]

Marlowe Hood of AFP wrote: “Denny's surprising pedigree was unlocked from a bone fragment unearthed in 2012 by Russian archeologists at the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia. "I initially thought that they must have screwed up in the lab," said senior author and Max Planck Institute professor Svante Paabo, who identified the first Denisovan a decade ago at the same site. Worldwide, fewer than two dozen early human genomes from before 40,000 years ago — Neanderthal, Denisovan, Homo sapiens — have been sequenced, and the chances of stumbling on a half-and-half hybrid seemed vanishingly small. \=/

“Or not. "The very fact that we found this individual of mixed Neanderthal and Denisovan origins suggests that they interbred much more often than we thought," said Slon. Paabo agreed: "They must have quite commonly had kids together, otherwise we wouldn't have been this lucky." A 40,000 year-old Homo sapiens with a Neanderthal ancestor a few generations back, recently found in Romania, also bolsters this notion. But the most compelling evidence that inter-species hanky-panky in Late Pleistocene Eurasia may not have been that rare lies in the genes of contemporary humans...Neanderthals and Denisovans might have intermingled even more but for the fact that the former settled mostly in Europe, and the latter in central and East Asia, the researchers speculated.” \=/

Laborious Discovering Denny

Denisovan research faces a basic problem of a paucity of fossils in Denisova Cave in Siberia.“It is a wonderful site,” says Tom Higham, deputy director of Oxford University’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit told The Guardian. “It is cool inside, so DNA in bones does not disintegrate too badly. However, nearly all the bones there have been chewed up by hyenas and other carnivores.” As a result, Denisova’s cave floor is littered with tiny, unidentifiable bone fragments. “You cannot tell whether a piece comes from a mammoth or a sheep – or a man or woman,” adds Higham. “Only a very few will be human, though they are certainly worth finding – they could tell us so much.” Current techniques for identifying bone fragments involve the time-consuming process of extracting and sequencing DNA. “That takes far too long to be practical,” says Higham. “There are tens of thousands of bits of bones here.”[Source: Robin McKie, The Guardian, November 24, 2018]

Higham and project leader Katerina Douka, of the Max Planck Institute in Jena, used a new technology called Zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry – ZooMs. Robin McKie wrote in The Guardian: Developed by Mike Buckley, at Manchester University, the technique, which is derived from food science research, exploits the fact that collagen, a protein fibre found in bone, can survive for hundreds of thousands of years. Every major mammal group has a distinctive type of collagen, and ZooMs can read its structure like a molecular barcode, identifying which animal was the originator of a particular bone. This makes it ideal for differentiating human and animal remains.

“We asked Anatoly Derevyanko and Mikhail Shunkov, who direct the cave’s excavations, for samples – and they gave us a big bag full of bits of bones. All the fragments were considered to be unidentifiable,” says Douka. The team began to prepare the bones. A 20mg slice was cut from each and placed in a test tube and given an identification code. After three months, 150 samples had been prepared. “That was nowhere near enough,” says Higham. So Douka and Higham asked their postgraduate students for a volunteer to work on the project. “No one came forward,” says Higham. “A week went by, then a fortnight. I was beginning to get worried. Then an Australian student, Samantha Brown, knocked on my door and volunteered to work the bones as part of her master’s dissertation. She saved the day.”

Over the next few weeks, Brown undertook the laborious task of cutting and labelling tiny slices from each bone fragment. “I eventually prepared about 700 samples,” she recalls. These were then taken to Manchester for analysis in Buckley’s laboratory. “The results showed we had a lot of cow bones, a few other animals but no humans,” says Brown. “It was very disappointing.” At that point, Brown could have left the project with honour. But she chose to go on. “Thank God she did,” says Higham. A further 1,500 Denisova bone samples were prepared by her and then taken to Manchester. This time, the results were spectacularly different. One bone, number 1,227, was identified as being from a human species. “We could not believe that it had actually worked. It was wonderful,” says Douka. Brown was also overjoyed. “It was unbelievably exciting. We had not only shown the technique works but we had found a hominin. And I had been prepared for the worst.”

It was tremendous news for the team. But their discovery lacked a key piece of information. Yes, they had found a human of some kind, but which species? To find out, the sample was taken to Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, whose team had sequenced the first Denisovan genome in 2010. Initial analysis showed that the bone was more than 50,000 years old and from a person who had been 13 or older when they died.

Neanderthals and Denisovans Interbred with a Mysterious Hominin 700,000 Years Ago.

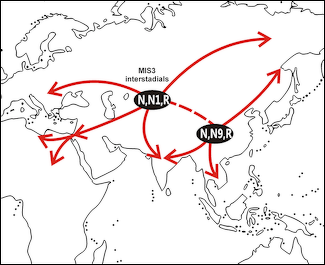

A study published in February 2020 showed that the ancestors of those Neanderthals and Denisovans once interbred with a mysterious population of ancient humans in Eurasia 700,000 years ago. “This continues the story that we've been seeing in studies throughout the past decade: There's lots more interbreeding between lots of human populations than we were aware of ever before," Alan Rogers, an anthropologist at the University of Utah and the lead author of the study, previously told Business Insider. "This discovery has pushed the time depth of those interbreedings much further back." [Source: Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, December 12, 2020]

In 2013 Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: “Scientists discovered that apparently Denisovans interbred with an unknown human lineage, getting as much as 2.7 to 5.8 percent of their genomes from it. This mystery relative apparently split from the ancestors of all modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans between 900,000 years and 4 million years ago, before these latter groups started diverging from each other. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, December 18, 2013]

Kay Prüfer, a computational geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, said enigmatic lineage could even potentially be Homo erectus, the earliest undisputed predecessor of modern humans. There are no signs this unknown group interbred with modern humans or Neanderthals. "Some unknown archaic DNA might have caught a ride through time by living on in Denisovans until we dug the individual up and sequenced it," Prüfer told LiveScience. "It opens up the prospect to study the sequence of an archaic (human lineage) that might be out of reach for DNA sequencing."

Oldest Known Human DNA Linked to Denisovans

homo sapien lineage

The oldest known human DNA — from the bone of a hominin living in what is now the Sima de los Huesos in Northern Spain, dated to approximately 400,000 years ago — appears to have belong to an unknown hominin, presumably a common ancestor of Denisovans and Neanderthals but with closer links to Denisovans than Neanderthals. Scientists detailed their findings on this in the December 5, 2013 issue of the journal Nature. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, December 4, 2013 \=]

Charles Q. Choi of Live Science wrote: “To discover more about human origins, researchers investigated a human thighbone unearthed in the Sima de los Huesos, or "Pit of Bones," an underground cave in the Atapuerca Mountains in northern Spain. The bone is apparently 400,000 years old. "This is the oldest human genetic material that has been sequenced so far," said study lead author Matthias Meyer, a molecular biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. "This is really a breakthrough — we'd never have thought it possible two years ago that we could study the genetics of human fossils of this age." Until now, the previous oldest human DNA known came from a 100,000-year-old Neanderthal from a cave in Belgium. \=\

“The Sima de los Huesos is about 100 feet (30 meters) below the surface at the bottom of a 42-foot (13-meter) vertical shaft. Archaeologists suggest the bones may have been washed down it by rain or floods, or that the bones were even intentionally buried there. This Pit of Bones has yielded fossils of at least 28 individuals, the world's largest collection of human fossils dating from the Middle Pleistocene, about 125,000 to 780,000 years ago. "This is a very interesting time range," Meyer told LiveScience. "We think the ancestors of modern humans and Neanderthals diverged maybe some 500,000 years ago." The oldest fossils of modern humans found yet date back to about 200,000 years ago.\=\

”The researchers reconstructed a nearly complete genome of this fossil's mitochondria — the powerhouses of the cell, which possess their own DNA and get passed down from the mother. The fossils unearthed at the site resembled Neanderthals, so researchers expected this mitochondrial DNA to be Neanderthal. Surprisingly, the mitochondrial DNA reveals this fossil shared a common ancestor not with Neanderthals, but with Denisovans, splitting from them about 700,000 years ago. This is odd, since research currently suggests the Denisovans lived in eastern Asia, not in western Europe, where this fossil was uncovered. The only known Denisovan fossils so far are a finger bone and a molar found in Siberia. "This opens up completely new possibilities in our understanding of the evolution of modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans," Meyer said.” \=\

Neanderthals and Denisovans Strengthened Our Immune System?

Research from Stanford, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the Institute Pasteur have suggested interbreeding with the Neanderthals strengthened the immune system of modern humans. Linda Marsa wrote in Discover: “When our ancestors mated with Neanderthals and Denisovans, a recently discovered archaic human group, they picked up some of their genes. Now researchers say that DNA inherited from these extinct hominins may have fortified the modern immune system. A team at Stanford University focused on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class 1 genes, which play a vital role in rallying the immune system to fight off bacteria and viruses. Because diseases can be endemic to specific regions of the world, these genes exist in thousands of versions, known as alleles. [Source: Linda Marsa, Discover, December 22, 2011

“To analyze the origin of these alleles, the scientists looked at bone marrow registries containing the HLA genes of millions of people from all parts of the globe. By comparing DNA from modern populations with the reconstructed genomes of Neanderthals and Denisovans, they discovered that several HLA variants from the archaic groups are still around. For example, the ancient gene for HLA-A, which helps the body resist viruses like Epstein-Barr, is present in half of all modern Europeans, more than 70 percent of Asians, and up to 95 percent of people in Papua New Guinea. Other ancient alleles are involved in the regulation of natural killer cells, essential for immune defense.

“Our ancestors’ liaisons with Neanderthals and Denisovans may have made them less susceptible to local infections, proposes Stanford immunologist Laurent Abi-Rached, giving them a survival advantage as they migrated out of Africa to Europe and Asia. “Breeding with our evolutionary cousins may have facilitated the spread of modern humans by preventing them from getting sick.”“

Human-Neanderthal-Denisovan Interbreeding: the Cause of Modern Allergies ?

Three genes inherited from Neanderthal may have given modern humans overly-sensitive immune systems, making them susceptible to allergies Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “Passionate encounters between ancient humans and their burly cousins, the Neanderthals, may have left modern people more prone to sneezes, itches and other allergies, researchers say. The curious legacy comes from three genes that crossed into modern humans after their distant ancestors had sex with Neanderthals, or their close relatives the Denisovans, more than 40,000 years ago. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian January 7, 2016]

“The three genes are among the most common strands of Neanderthal and Denisovan-like DNA found in modern humans, suggesting they conferred an evolutionary advantage. They probably boosted the immune system, since the genes are involved in the body’s first line of defence against pathogens such as bacteria and fungi. But people who carry the three genes seem to pay a price in the form of an overly-sensitive immune system. One study by the US genetics company 23andme found that carriers of the genes were more likely to have asthma, hay fever and other allergies. |=|

“The genes are thought to have spread through modern humans when small groups of pioneers who left Africa met and had sex with Neanderthals already long at home in Eurasia. Unlike the new arrivals, the Neanderthals had spent 200,000 years adapting to life in the region, and their immune systems had become tuned to the new infections they faced. “A small group of modern humans leaving Africa would not carry much genetic variation,” said Janet Kelso, who led the research at the Max Planck Institute for evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. “You can adapt through mutations, but if you interbreed with the local population who are already there, you can get some of these adaptations for free.” |=|

“Kelso’s team scanned the genomes of modern day humans for evidence of Neanderthal or Denisovan genes and then looked at how common they were in people from around the world. Among the three immune system genes that stood out, two closely matched Neanderthal DNA. The most common was found in all non-Africans, the other only in Asians. The third gene was more similar to Denisovan DNA and much rarer, found in only a handful of people from Asia who took part in the study.

“The findings suggest that modern humans inherited Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in three waves depending on where and when the groups met. The genes proved so beneficial that they remain in our genomes to this day. The study is reported in the American Journal of Human Genetics.The work is backed up by separate research published in the same journal by scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. Geneticist Lluis Quintana-Murci analysed DNA from participants in the 1000 Genomes Project and compared their DNA with ancient human genomes. He focused specifically on 1500 immune genes and found that most adaptations occurred in the past 6,000 to 13,000 years, when humans shifted from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to farming. |=|

“But Quintana-Murci said the most striking discovery was of the same three genes that Kelso found. In his study, the trio of genes were among the most common Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA found in modern people. “Interbreeding with archaic humans does indeed have functional implications for modern humans,” Kelso said. “The most obvious consequences have been in shaping our adaptation to our environment - improving how we resist pathogens and metabolise novel foods.” “For all the benefits they bring, the downsides of Neanderthal genes might not be so bad. “They might have increased our susceptibility,” said Kelso. “But I wouldn’t go so far as to say Neanderthals gave us allergies.” |=|

Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA Found in Ancient South Americans

Scientists investigating the genomes of ancient South Americans were surprised to find the presence of DNA from Neanderthals and Denisovans there. The research — which interrogated human remains from Brazil, Panama, and Uruguay and also revealed migration patterns of these early South Americans across the continent — is the first time that Denisovan or Neanderthal ancestries have been reported in ancient South Americans. The research is published in November 2022 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B [Source: Isaac Schultz, Gizmodo, November 4, 2022].

“The presence of these ancestries in ancient Native American genomes can be explained by episodes of interbreeding between anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals and Denisovans, which should have occurred millennia before the first human groups entered the Americas through Beringia,” said Andre Luiz Campelo dos Santos, an archaeologist at Florida Atlantic University and the study’s lead author. The research affirmed archaeological evidence of north-to-south migration toward South America, but also indicated migrations occurred in the opposite direction, along the Atlantic coast.

Gizmodo reported: In the recent work, the team compared genomes from ancient human remains found in Brazil, Panama, and Uruguay with ancient remains from across the United States (including Alaska, to represent ancient Beringia), Peru, and Chile. Two ancient whole genomes from teeth found in northeast Brazil that were included in the study were newly sequenced. In addition to the ancient human genomes featured in the analysis, the team looked at present-day worldwide genomes and DNA sequences taken from Denisovan and Neanderthal remains from Russia. The latter remains are over tens of thousands of years old (Neanderthals disappear from the fossil record around 40,000 years ago), but some of the human remains are just 1,000 years old, according to the team’s analysis.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the analysis revealed chunks of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA in the ancient South American genomes, as well as Australasian signals in the remains of one individual from Panama. The Australasian signal was previously detected in ancient remains in southeastern Brazil and is present today in the Sirui people of Amazonia. The ancient individuals in Panama and Brazil had more Denisovan ancestral signals in their genomes than they did Neanderthal-specific ancestry. Today, the opposite is the case in humans around the world: We have more Neanderthal in us than Denisovan.

According to study co-author John Lindo, an anthropologist at Emory University, the Denisovan ancestry was mixed into the South American humans as long as 40,000 years ago, and its signal persisted in the remains of a 1,500-year-old individual from Uruguay. “The Australasian ancestry in the Americas is perplexing, as this has been reported for isolated samples widely separated by space and time and doesn’t show a clear pattern,” said Iosif Lazaridis, a geneticist at Harvard University who was not affiliated with the work, in an email to Gizmodo. “Such ancestry may have spread with Austronesian migrations across the Pacific (a non-Beringian route), as Austronesians were able seafarers,” Lazaridis added, noting that, despite the possibility, there is no evidence Austronesians made it to the Americas.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024