Home | Category: Neanderthal Life

NEANDERTHAL MEAT EATING

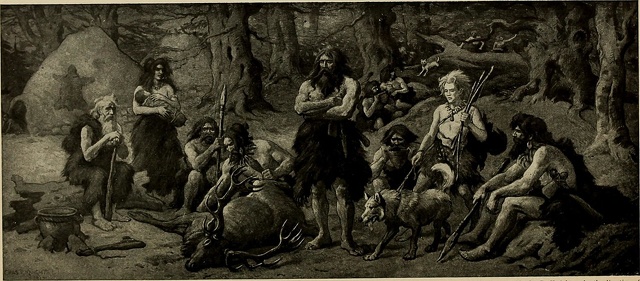

Extinct cave bear

Based on the presence of animal bones at Neanderthal sites, Neanderthals ate large animals such as cave bears,aurochs (large, long-horned wild oxen), bison, elk and even wooly mammoths. It was previously thought Neanderthals scavenged these animals and were incapable of hunting them, but recent evidence suggests that they hunted these animals in groups (See Below).

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: The bones of large herbivores found at Neanderthal sites across Europe and Asia seem to indicate that their meals consisted of one course: meat. Several new studies, however, reveal a wider variety of menu options. Isotope analysis of bones from Kudaro 3 in the Caucasus Mountains (in a disputed area of Georgia) show that Neanderthals there dined on salmon. Fish was also on the menu in southeastern France, at Abri du Maras, where analysis of the residue left on stone tools shows that Neanderthals also ate duck and rabbit.[Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2014]

Bones found at Neanderthal sites have marks from stone tools, most likely made when removing meat from them. A hearth found in one Neanderthal cave is not believed to have been used in cooking but rather to prepare the carcasses (heating the bones, for example, makes it easier break them to remove the marrow inside). It has been suggested that fire may have been used not so much to cook food but to defrost frozen meat so it could eaten.

Ewen Callaway wrote in NewScienceLife: “Chemical signatures locked into bone suggest the Neanderthals got the bulk of their protein from large game, such as mammoths, bison and reindeer. The anatomically modern humans that were living alongside them had more diverse tastes. As well as big game, they also had a liking for smaller mammals, fish and seafood. “It seems modern humans had a much broader diet, in terms of using fish or aquatic birds, which Neanderthals didn’t seem to do,” says Michael Richards, a biological anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany and the University of British Columbia in Canada.” [Source: Ewen Callaway, NewScienceLife, August 12, 2009]

See Separate Articles:

DIET OF OUR HUMAN ANCESTORS europe.factsanddetails.com;

STUDYING PREHISTORIC DIETS factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL FOOD AND DIET europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL HUNTING: METHODS, PREY AND DANGERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FOOD OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS (100,000-10,000 YEARS AGO) factsanddetails.com;

MEAT EATING BY MODERN HUMANS 200,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO europe.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING: BOWS, ARROWS AND ECOLOGY factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING AND MEAT PROCESSING TECHNIQUES europe.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALOPITHECUS AND EARLY HOMININ FOOD, DIET AND EATING HABITS ; factsanddetails.com ;

HOMO ERECTUS FOOD factsanddetails.com ;

HOMININS, HOMO ERECTUS AND FIRE factsanddetails.com ;

HOMININS, HOMO ERECTUS AND COOKING factsanddetails.com ;

MEAT EATING BY HOMININS 500,000 to 80,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Arrowpoints, Spearheads, and Knives of Prehistoric Times” by Thomas Wilson (2022) Amazon.com

“A View to a Kill: Investigating Middle Palaeolithic Subsistence Using an Optimal Foraging Perspective” (2008) by G. L. Dusseldorp Amazon.com

“Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human” by Richard Wrangham Amazon.com;

“Evolution's Bite: A Story of Teeth, Diet, and Human Origins” by Peter Ungar (2017) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Cookery, Recipes and History,” by Jane Renfrew (English Heritage, 2006) Amazon.com

“Meat-Eating and Human Evolution” by Craig B. Stanford, Henry T. Bunn Amazon.com;

“Evolution of the Human Diet: The Known, the Unknown, and the Unknowable” by Peter S. Ungar Amazon.com;

The Paleo Diet Revised: by Loren Cordain Amazon.com;

“The Smart Neanderthal: Bird catching, Cave Art, and the Cognitive Revolution”

by Clive Finlayson Amazon.com;

:Prehistoric Investigations: From Denisovans to Neanderthals; DNA to stable isotopes; hunter-gathers to farmers; stone knapping to metallurgy; cave art .by Christopher Seddon Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science Is Rewriting Their Story”

by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse (2022) Amazon.com;

Neanderthals Were 'Top-Level Carnivores,' Tooth Analysis Suggests

Tooth analysis suggests. Neanderthals were “top-level carnivores”. Ben Turner wrote in Live Science: Scientists made the discovery by analyzing the concentrations of different versions, or isotopes, of zincs in a Neanderthal tooth found in Gabasa, Spain. That analysis revealed that the tooth's owner was a "top-level carnivore", the researchers wrote, in a study published Oct. 17, 2022, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and was far less reliant on eating plants than previously surveyed Neanderthals in the region. [Source: Ben Turner, Live Science, October 29, 2022]

To study the diets of ancient homininians — relatives of humans more closely related to us than chimpanzees — scientists usually look at the concentrations of nitrogen isotopes in bone collagen. The body absorbs and stores nitrogen from food in this collagen. Plants vary in how much nitrogen-15 they absorb, but as you go up the food chain, animal tissues accumulate more and more nitrogen-15 relative to nitrogen-14. If an animal has higher ratios of nitrogen-15 to nitrogen-14, it is likely that the animal ate more meat. But the technique isn't perfect: It only works on bones less than 50,000 years old that were preserved in temperate climates; and it doesn’t differences in the baseline level of nitrogen-15 in different plants.

As the Gabasa tooth could be anywhere between 100,000 to 200,000 years old, the researchers turned to a new technique that analyzed zinc isotopes in the teeth enamel. As animals go up the food chain, their tissue tends to store more zinc-64 relative to zinc-66. The scientists found that the Neanderthal tooth had very low levels of the isotope zinc-66, meaning the tooth was probably from a dedicated meat eater.

Further analysis of the isotopes in the enamel, taken alongside analyses of broken bones found at the site, also reveal that the neanderthal group ate bone marrow but did not consume the blood of their prey. Other chemical clues from the tooth like calcium, taken with the zinc values from the oldest part of the enamel, point to its past owner having been weaned off milk before the age of two. To confirm their theory that most Neanderthals had carnivorous diets, the researchers plan to use their analysis technique on more teeth from Neanderthals found in other parts of Europe, where different ecosystems may have stretched their diets to include plants. Whether any of these populations munched on enough plants to be classified as omnivores is still an open question.

"Plant consumption existed, but it was probably a very minor part of Neanderthal's diets," first author Klervia Jaouen, a researcher at Géosciences Environnement Toulouse in France, told Live Science. "However, we need more investigations to confirm this. So far, isotope researches suggest that Neanderthal's diets were quite homogeneous (terrestrial carnivores) but other approaches reveal much more diversity."

Neanderthal Diet: 80 Percent, Usually Fresh, Meat

Fossil analysis suggests Neanderthals ate a diet that was 80 percent meat. Brooks Hays of UPI wrote: “New isotopic analysis suggests prehistoric humans ate mostly meat. As detailed in a new study published in the journal Quaternary International, the Neanderthal diet consisted of 80 percent meat, 20 percent vegetables. Researchers in Germany measured isotope concentrations of collagen in Neanderthal fossils and compared them to the isotopic signatures of animal bones found nearby. In doing so, scientists were able to compare and contrast the diets of early humans and their mammalian neighbors, including mammoths, horses, reindeer, bison, hyenas, bears, lions and others.\~/ [Source: Brooks Hays, UPI, March 19, 2016 \~/]

Lead researcher Herve Bocherens, a professor at the University of Tubingen’s Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment, said: “Previously, it was assumed that the Neanderthals utilized the same food sources as their animal neighbors. However, our results show that all predators occupy a very specific niche, preferring smaller prey as a rule, such as reindeer, wild horses or steppe bison, while the Neanderthals primarily specialized on the large plant-eaters such as mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses.” \~/

All of the Neanderthal and animal bones, dated between 45,000 and 40,000 years old, were collected from two excavation sites in Belgium. Researchers have long debated the precise diet of early humans, but the latest study is the first to nail down precise percentages. Bocherens and his colleagues are hopeful their research will shed light on the Neanderthals’ extinction some 40,000 years ago. “We are accumulating more and more evidence that diet was not a decisive factor in why the Neanderthals had to make room for modern humans,” he said. \~/

Similar research in France published in the journal PNAS in 2019 indicated Neanderthals favored fresh herbivores and eschewed rotten meat. According to Cosmos.org: The finding, based on measures of nitrogen and carbon isotopes in two samples of Neanderthal collagen gathered from two sites in France, confirm a carnivorous diet. It also does not support previously published suggestions that Neanderthals dined on putrid carrion left behind by other carnivores, or freshwater fish. The latest research, led by Klervia Jaouen from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, tested carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios on single amino acids from collagen samples from Neanderthals recovered from sites at Les Cottés and Grotte du Renne. They conducted similar tests on faunal remains recovered from the same area. [Source: Cosmos magazine.com, Ancientfoods March 2, 2019]

The Neanderthal collagen, showed “exceptionally high [nitrogen] isotope ratios in their bulk bone or tooth collagen”. The results, Jaouen and colleagues report, were wholly consistent with “mammal meat consumption”. There was no need to invoke other food sources, such as fish or mushrooms, nor food processes, such as cooking or fermentation arising from rot, to explain the readings. The scientists acknowledge that their results do not preclude the occasional consumption of other food types and sources. However, they say, the isotope values of the Neanderthals strongly supports the contention that their main protein sources was “due to the consumption of different herbivores from different environments”.

Meat Diet Gave Neanderthals Barrel Bodies?

Neanderthals ate plants but subsisted on animals, leading to larger livers and kidneys and wider thoraxes, Israeli scientists assert. Ruth Schuster wrote on haaretz.com,. Neanderthals and humans” had their anatomical differences, among them wider pelvises and rib-cages. Now archaeologists from Tel Aviv University suggest that the reason for these anatomical discrepancies is that Neanderthals ate mostly meat, while Homo sapiens has had a more variegated diet. [Source: Ruth Schuster, haaretz.com, May 21, 2016 ]

“It isn’t new that the Neaderthal ribcage and pelvis are wider than man’s. But until now scientists had assumed that had to do with Neanderthals having greater energetic demands than Homo sapiens. Whether or not that was a factor, the Tel Aviv archaeologists think the reason may have been more diet-oriented. Studies of coprolites (fossil feces) have shown that Neanderthals also ate plant matter. But a range of studies have shown the Neanderthal diet to be heavily biased towards protein – meat and fat. Chemical studies of their bones has indicated that a bigger proportion of their diet came from meat than cave bears found at the same sites; analysis of the isotopes in Neanderthal collagen shows their diet consisted mainly of herbivores, and megafauna, such as sloths, mammoths and prehistoric rhinoceroses, as well as plants.

“In the frigid winters of the Ice Age, large animals may have flourished, but their fat content would have been reduced. A theoretical model created by the Israeli scientists predicts that during glacial winters, when carbohydrates weren’t available and fat was scarce, the Neanderthals needed to get more caloric intake meat, and evolved to better convert the protein into life-giving energy.

“To contend with all that protein, their livers, which are responsible for protein metabolism, had to become larger. So their lower thoraxes did too. The more protein is metabolized, the more toxins such as urea need removal from the body. As their protein metabolism increased, the Neanderthals needed more renal capacity – an enlarged bladder and kidneys – to get rid of the toxins, could, evolutionarily, be the reason why the Neanderthal pelvis is wider than ours.

“Given that high protein consumption is associated with larger liver and kidneys in animal models, it appears likely that the enlarged inferior section of the Neanderthals’ thorax and possibly, in part, also his wide pelvis, represented an adaptation to provide encasement for those enlarged organs,” write the scientists. “Early indigenous Arctic populations who primarily ate meat also displayed enlarged livers and the tendency to drink a lot of water, a sign of increased renal activity,” Ben-Dor points out.”

Neanderthal Mammoth Buffet in England 215,000 Years Ago?

In 2021, scientists announced they had discovered Britain’s oldest “buffet”, likely consumed by Neanderthals, while examining the remains of mammoth hunt. The Telegraph reported: “A mammoth graveyard unearthed in Wiltshire has been found to be 215,000 years old, with the four-meter-tall animals perishing during a period when the British Isles were on the cusp of an Ice Age “The discovery of stone axes near mammoth bones with potential cut marks could indicate the site of a “massive buffet”, experts have said, and implements used to carve up the feast suggest Britain’s Neanderthals had outdated tools compared to their continental cousins.

Research into the site features in a new BBC documentary with Sir David Attenborough and the University of East Anglia‘s Prof Ben Garrod. “Prof Garrod said: “This is gold dust. It could be that Neanderthals were camping there, maybe they caused the deaths of these animals, chasing them into the mud and enjoying basically a massive buffet. “Maybe they found them there already and got a free meal.” [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, December 18, 2021]

“Research covered in the programme reveals that 215,000 years ago the site was a slow-moving part of the prehistoric River Thames. It was treacherous enough to trap the steppe mammoths, which may have been corralled into the river. The silty conditions of the waterway have perfectly preserved the site, with Prof Garrod saying: “It is like a crime scene, nothing has been moved. “We have these stone tools, we have these bodies, and we do have evidence or what looks like (butchery) marks on the bones — but we have to be very careful that we eradicate all other suspects. “If the lab shows the cut-marks are human made, our site will be one of the oldest scientifically excavated sites with Neanderthals butchering mammoths in Britain.”

“While experts will assess whether the Neanderthals butchered the mammoths in situ on the banks of the river, early analysis has indicated that the stone axes they were using were not the height of Middle Palaeolithic technology, compared with stone tools found elsewhere in Europe.“Prof Garrod said: “What we have found is that these Neanderthals in Britain were using stone tools that were, you could say, ‘old fashioned’ compared to the technology you would expect from that time and place. “It was a bit like my parents using an old Nokia when I’m using an iPhone. It might have been a case of if it ain’t broke don’t fix it, or it could indicate they were quite separated from other tool-making cultures.”

Neanderthals in Southern Spain Lived Mainly on Seafood 150,000 Years Ago

Neanderthals occupying caves in southern Spain lived on a diet of seafood earlier than previously thought — 150,000 years ago — archaeological findings show. Fiona Govan wrote in The Telegraph: “Archaeological examination of a cave in Torremolinos unearthed early tools used to crack open shellfish collected off rocks along the Iberian coast and found fossilised remains of the early meals. The discovery is the earliest of its kind in northern Europe and shows that early man were fish eaters in Europe some 100,000 years earlier than previously thought and that that early coastal cavemen supplemented their hunter/gatherer diet of nuts, fruits and meat from animals such as antelopes and rabbits with seafood. [Source: Fiona Govan, The Telegraph, September 15, 2011 /~/]

“A team of archaeologists from Seville University and scientists from the National Council for Scientific Investigation (CSIC) published their research this week after a lengthy investigation involving the scientific dating of fossilised remains from the cave. The Cueva Bajondillo on Andalusia’s southern coast near Malaga contained remains of burned mussel shells and barnacles indicating that Middle Paleolithic hominins had collected and cooked the shellfish for consumption. /~/

“The discovery suggests that Neanderthals in Europe and Archaic Homo sapiens in Africa were following parallel behavioural trajectories but with different evolutionary outcomes, the paper claims. “It provides evidence for the exploitation of coastal resources by Neanderthals at a much earlier time than any of those previously reported,” said Miguel Cortés Sánchez who led the Seville University team. “The use of shellfish resources by Neanderthals in southern Spain started some 150,000 years ago,” the paper concluded. “It was almost contemporaneous to Pinnacle Point (in South Africa) when shellfishing is first documented in archaic modern humans.”“ /~/

Hominins Ate Elephants' Meat and Bone Marrow in Madrid 80,000 Years Ago

According to the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology: “Humans that populated the banks of the river Manzanares (Madrid, Spain) during the Middle Palaeolithic (between 127,000 and 40,000 years ago) fed themselves on pachyderm meat and bone marrow. This is what a Spanish study shows and has found percussion and cut marks on elephant remains in the site of Preresa (Madrid). It is not clear which hominins consumed the meat and marrow, but you would assume it was Neanderthals as they were established in the region around 80,000, while modern humans didn’t really start to make their presence felt until around 40,000 years ago, [Source: Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology, April 24, 2012, Paper: Yravedra, J.; Rubio-Jara, S.; Panera, J.; Uribelarrea, D.; Pérez-González, A. "Elephants and subsistence. Evidence of the human exploitation of extremely large mammal bones from the Middle Palaeolithic site of PRERESA (Madrid, Spain)". Journal of Archaeological Science 39 (4): 1063-1071, april 2012. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2011.12.004]

“In prehistoric times, hunting animals implied a risk and required a considerable amount of energy. Therefore, when the people of the Middle Palaeolithic (between 127,000 and 40,000 years ago) had an elephant in the larder, they did not leave a scrap. Humans that populated the Madrid region 84,000 years ago fed themselves on these prosbocideans' meat and they consumed their bone marrow, according to this new study. Until now, the scientific community doubted that consuming elephant meat was a common practice in that era due to the lack of direct evidence on the bones. It is still to be determined whether they are from the Mammuthus species of the Palaleoloxodon subspecies.

“The researchers found bones with cut marks, made for consuming the meat, and percussion for obtaining the bone marrow. "There are many sites, but few with fossil remains with marks that demonstrate humans' purpose" Jose Yravedra, researcher at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) and lead author of the study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science points out to SINC.

“This is the first time that percussion marks that showed an intentional bone fracture to get to the edible part inside have been documented. These had always been associated with tool manufacturing but in the remains found, this hypothesis was discarded. The tools found in the same area were made of flint and quartzite. The team, made up of archaeologists, zooarchaeologists and geologists from UCM, the Institute of Human Evolution in Africa (IDEA) in Madrid and the Spanish National Research Centre for Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, collected 82 bones from one elephant, linked to 754 stone tools, in an area of 255 metres squared, in the site of Preresa, on the banks of the river Manzanares.

“In the case of the cut marks on the fossil remains, these add to the "oldest evidence of exploiting elephants" in the site of Áridos, close to the river Jarama, according to another study published by Yravedra in the same journal. "There are few records about the exploitation of elephants in Siberia, North America and central Europe", the zooarchaeologist explains.

“The internal organs were what the predator ate first, be they human or any kind of carnivore. The prehistoric signs of the banquet help researchers to find out who was the first to sit down at the table, as the risk of hunting an elephant posed the question as to whether humans hunted it or were scavengers. "This is the next mystery to be solved" Yravedra replies, who reminds us that there is evidence of hunting in other smaller animals in the same site. However, due to the thickness of fibrous membranes and other elephant meat tissues, humans did not always leave marks on the bones. "And for this reason, sometimes it is difficult to determine if humans used their meat".

Neanderthals Ate Sharks, Seals. Eels and Dolphins

Neanderthals in present-day Portugal ate sharks, dolphins, fish, mussels and seals according to a study published in March 2020 in the journal Science.. The BBC reported: Scientists found evidence for an intensive reliance on seafood at a Neanderthal site in southern Portugal. Neanderthals living between 106,000 and 86,000 years ago at the cave of Figueira Brava near Setubal were eating mussels, crab, fish — including sharks, eels and sea bream — seabirds, dolphins and seals. [Source: Paul Rincon, Science editor, BBC News website, 26 March 2020]

The research team, led by Dr João Zilhão from the University of Barcelona, Spain, found that marine food made up about 50 percent of the diet of the Figueira Brava Neanderthals. The other half came from terrestrial animals, such as deer, goats, horses, aurochs (ancient wild cattle) and tortoises.

Some of the earliest known evidence for the exploitation of marine resources by modern humans (Homo sapiens) dates to around 160,000 years ago in southern Africa. A few researchers previously proposed a theory that the brain-boosting fatty acids seafood contributed to enhanced cognitive development in early modern humans. This, the theory goes, could help account for a period of marked invention and creativity that started among modern human populations in Africa around 200,000 years ago. It might also have assisted modern humans to outcompete other human groups such as the Neanderthals and Denisovans.

But the researchers found that the Neanderthal inhabitants of Figueira Brava relied on the sea in a scale comparable to modern human groups living at a similar time in southern Africa. Commenting on the findings, Dr Matthew Pope, from the Institute of Archaeology at UCL, UK, said: "Zilhão and the team claim to have identified 'middens'. This is a shorthand for humanly created structures (piles, heaps, mounds) formed almost entirely of shell. "They are important as they suggest a systematic and organised behaviour, from collection to processing to discard." Dr Pope added: "In later periods across the world, coastal shell-hunter-gatherers seem to invest in these structures in monumental ways, even having burials within them. So to describe these accumulations as 'middens' is a bold and loaded step. Certainly, they make a strong case that these are comparable to similar accumulations in the Middle Stone Age of Africa."

Neanderthals Cooked Brown Crabs 90,000 Years Ago in Portugal

Neanderthals who occupied Gruta de Figueira Brava in Portugal 90,000 years ago seemed to be especially fond of cooking and eating brown crabs (Cancer pagurus). Mariana Nabais, a zooarchaeologist who studies animal remains that are found at archaeological sites, reported on this in a study published February 7, 2024 in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology. Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: She and her team studied the deposits of stone tools, shells, and bones uncovered at Figueira Brava, south of the capital city of Lisbon. While they found a wide variety of shellfish in the deposits, remnants of brown crab were the most common in the deposits. Neanderthals possibly used low tide pools during the summer to harvest the crustaceans, according to the team. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, February 7, 2023]

Most of the crabs were adults which would yield roughly seven ounces of meat. “I was very surprised about the unexpected large amount of crab remains, and their large size, similar to those we eat today,” says Nabais. The team looked at the patterns of damage on the crab’s shells and claws and did not find any marks from rodents or evidence that birds had broken into the shells. When looking for signs of butchery and percussion marks from tools, they found fracture patterns in the shells that indicate that the shells were intentionally broken up to access the meat.

Burns were found on about eight percent of the crab shells, indicating that Neanderthals were roasting the crabs in addition to harvesting them. Comparing the black burns on the shells with studies of other mollusks showed that the crabs were heated to 572 to 932 degrees Fahrenheit, a typical temperature for cooking. “Our results add an extra nail to the coffin of the obsolete notion that Neanderthals were primitive cave dwellers who could barely scrape a living off scavenged big-game carcasses,” Nabais said in a statement. “Neanderthals in Gruta da Figueira Brava were eating a lot of other marine resources, like limpets, mussels, clams, fish, as well as other terrestrial animals, such as deer, goats, aurochs and tortoises,” According to Nabais, it is impossible to know why Neanderthals chose to harvest brown crabs or if they attached any significance to eating them, but consuming them would have given added nutritional benefits.

Neanderthals Ate Salmon in the Caucasus 45,000 Years Ago

Phys.org reported: “In a joint study, Professor Hervé Bocherens of the University of Tübingen, Germany, together with colleagues from the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg, Russia and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels, Belgium have found at a cave in the Caucasus Mountains indirect hints of fish consumption by Neandertals. Bone analyses ruled out cave bears and cave lions to have consumed the fish whose remains were found at the Caucasian cave. [Source: phys.org, September 17, 2013 =]

“On the northern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains, called Kudaro 3, the bone fragments of large salmon, migrating from marine water to their freshwater spawning places, were found in the Middle Palaeolithic archaeological layers, dated to around 42 to 48,000 years ago, and probably deposited by Neandertals. Such remains suggested that fish was consumed by these archaic Humans. However, large carnivores, such as Asiatic cave bears (Ursus kudarensis) and cave lions (Panthera spelaea) were also found in the cave and could have brought the salmon bones in the caves. =

“To test this hypothesis, the possible contribution of marine fish in the diet of these carnivores was evaluated using carbon, nitrogen and sulphur isotopes in faunal bone collagen, comparing these isotopic signatures between predators and their potential prey. The results indicate that salmons were neither part of the diet of cave bears (they were purely vegetarian, like their European counterparts) or cave lions (they were predators of herbivores from arid areas). =

“This study provides indirect support to the idea that Middle Palaeolithic Hominins, probably Neandertals, were able to consume fish when it was available, and that therefore, the prey choice of Neandertals and modern humans was not fundamentally different,” says Hervé Bocherens. He assumes that more than diet differences were certainly involved in the demise of the Neandertals.” =

Neanderthals Got 'Surfer's Ear,' Suggesting They Swam and Dived for Seafood in Cold Water

Research published in PLOS One in August 2019 revealed that abnormal bony growths in the ear canal, also called "surfer's ear" and often seen in people who take part in water sports in colder climates, occurred frequently in Neanderthals. The findings seems to suggest they were frequently involved in fishing and gathering seafood. "It reinforces a number of arguments and sources of data to argue for a level of adaptability and flexibility and capability among the Neanderthals, which has been denied them by some people in the field," lead author Erik Trinkaus of Washington University told AFP. [Source: AFP, August 15, 2019]

AFP reported: “That's because in order to be successful at fishing or hunting aquatic mammals, "you have to be able to have a certain minimal level of technology, you need to be able to know when the fish are going to be coming up the rivers or going along the coast — it's a fairly elaborate process," he said.Trinkaus and his colleagues, Sebastien Villotte and Mathilde Samsel from the University of Bordeaux, looked at well-preserved ear canals in the remains of 77 ancient humans including Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens found in Europe and west Asia. While early modern humans had similar frequencies of the bony growths as humans today do, and which are known medically as "external auditory exostoses," the condition was present in about half the 23 Neanderthal remains from 100,000 to 40,000 years ago.

“Exostoses are often asymptomatic but can produce earwax impaction and lead to infections and progressive loss of hearing. Such growths were first noted by French paleontologist Marcellin Boule in a classic 1911 monograph on the Neanderthal skeleton, but were never studied systematically until now. The authors wrote that their finding builds on previous scattered observations of Neanderthals exploiting aquatic resources, though archaeological proof in the form of fish remains are harder to come by because many of the former coastal sites are now underwater.

In 2020, Archaeology magazine reported: Analysis of shell tools from Grotta dei Moscerini suggests that, 100,000 years ago, some Neanderthals were capable of diving for clams in shallow water. While the cave’s Neanderthal inhabitants are known to have collected dead clams on the seashore, the new research indicates that some of the bivalves were harvested live, directly from the seafloor. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

Neanderthals — First Known Bird Eaters — Fond of Pigeons

Neanderthals are the first known hominin bird eaters. They appear to have caught, butchered and cooked wild pigeons long before modern humans regularly are bird meat a study, published in the journal Scientific Reports in August 2014, said, on Thursday. Brian Reyes wrote in phys.org: “Close examination of 1,724 bones from rock doves, found in a cave in Gibraltar and dated to between 67,000 and 28,000 years ago, revealed cuts, human tooth marks and burns, said the study. This suggested the doves may have been butchered and then roasted, wrote the researchers—the first evidence of hominins eating birds. [Source: Brian Reyes, phys.org, August 7, 2014 ^*^]

“And the evidence suggested Neanderthals ate much like a latter-day Homo sapiens would tuck into a roast chicken, pulling the bones apart to get at the soft flesh. “They liked what we like and went for the breasts, the drumsticks and the wings,” study author Clive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar Museum, told journalists of the bone analysis. “They had the knowledge and technology to do this.”

“The scarred remains were from rock doves—a species that typically nests on cliff ledges and the entrance to large caves—and the ancestors of today’s widespread feral pigeon. The discarded remains were from a time that the cave was occupied by Neanderthals and subsequently by humans. It was long thought that modern humans were the first hominins to eat birds on a regular basis. Yet at Gorham’s Cave, “Neanderthals exploited Rock Doves for food for a period of over 40,000 years, the earliest evidence dating to at least 67,000 years ago,” said the paper. ^*^

“And these were not sporadic meals, as borne out by “repeated evidence of the practice in different, widely spaced” parts of the cave. “Our results point to hitherto unappreciated capacities of the Neanderthals to exploit birds as food resources on a regular basis,” the team wrote. “More so, they were practising it long before the arrival of modern humans and had therefore invented it independently.” Finlayson said the bone analysis added to a growing body of evidence that Neanderthals were more sophisticated than was once widely believed. “This makes them even more human,” he said. ^*^

“Only a small proportion of bones found in regions of the cave inhabited by Neanderthals had cut marks on them, but the authors pointed out that rock doves were small and easy to eat without utensils. “After skinning or feather removal, direct use of hands and teeth would be the best way to remove the meat and fat/cartilage from the bones,” they wrote. “The proof of this is the human toothmarks and associated damage observed on some dove bones.” It was not known how the birds were captured, though the team speculated they would have been relatively easy to snatch from their nests “by a moderately skillful and silent climber” The researchers conceded the scorch marks were not conclusive proof of cooking, as they could be from waste disposal or accidental burning.” ^*^

Neanderthal Hunting

To keep their stocky bodies going in a cold climate, Duke University paleoanthropologist Steven Churchill estimates that a typical Neanderthal male needed to burn 5,000 calories a day, almost what cyclists competing in the Tour de France burn each day. To achieve this end some scientists argue Neanderthal needed to hunt large and medium-size game such as horses, deer, bison and wild cattle.

Studies of nitrogen levels found in a 33,000-year-old Neanderthal jawbone and skull, indicate that Neanderthals mostly ate animals, not plants. An inference that can be drawn from this is that Neanderthals were active hunters not scavengers and thus had an organized society that could hunt large animals. If they were scavengers they would more like have had to eat other kinds of food to tide them over when they couldn't find meat.

Scientists believe that Neanderthals initially competed with wolves, hyenas, lions and other predators for easy kills such as newly born calves and later developed strategies for hunting larger prey in groups.

Neanderthal tools were found with mammoth bones at the site of an ancient water hole in southern England. The mammoth bones showed the presence of carcass beetles and carnivore bites which suggests that maybe the Neanderthals scavenged rather than hunted the mammoths.

See Separate Article: NEANDERTHAL HUNTING factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024