Home | Category: Neanderthals

RANGE AND SIZE OF NEANDERTHAL POPULATIONS

Range of Neanderthals

Neanderthals lived mainly in Europe and migrated as far south as Israel and Spain during the ice ages. Flourishing in a relatively cold ice-age climate for 200,000 years, they lived in Europe at that time when it was covered by woods and grasslands that supported large herds of horses, reindeer, bison and species adapted for cold weather. During occasional subtropical periods that lasted for around 10,000 years or less, hippos lived in the Thames and hyenas and lions roamed parts of Russia. Scientists theorize that the Neanderthals arrived from a place with a warm climate, perhaps migrating south during the winter until they adapted to the colder climate.

Neanderthal remains have been found as far east as Uzbekistan, the Altai region and Siberia as far south as Israel and Spain, as far west as England and as far north as northern Germany, the Czech Republic and the Arctic Circle of Russia Scientists estimated that even at the height of their occupation of western Europe there were never more than 15,000 of them. This conclusion was reached from DNA studies that show very little genetic diversity, a sign of a small population.

The remains of more than 400 Neanderthal individuals, including 30 relatively complete skeletons, have been found. Many specimens have been found in Germany, Italy, Spain and France. Famous discovery site include the Neander Valley, near Dusseldorf, Germany, where the first Neanderthal was discovered in 1856; La Ferrassie, France, where a complete skull was found in 1909 (Housed in Musée de l'Homme, Paris).

Well-preserved Neanderthals have been found in El Sidron in Spain, Mezmaiskaya in Russia and Feldhofer in the Neander Valley of Germany. The remains of 75 Neanderthals were found in Vindija cave in the Croatian village of Krapina, 30 miles north of Zagreb. The remains include 874 bones fragments. All these specimens have given scientists a lot of material to work from, which is why we know a lot more about Neanderthals than we do about other species of early man.

In 1994, one hundred forty 43,000-year-old Neanderthal bones were found in El Sidorn cave, in an area of upland forests in the Spanish province of Asturias, just south of the Bay of Biscay after some spelunkers noticed two human mandibles jutting out of the soil in a gallery of the cave. After entering the cave by lowering oneself on a rope it takes about 10 minutes to reach “Gallery of Bones.” As of 2008. 1,500 bone fragments had been recovered from at least nine Neanderthals — including five young adults, two adolescents and a three-year-old child. Shortly after the nine died the ground below them collapsed, depositing their remain in limestone hollow where a flood covered them with sediment, allowing some of their DNA to be preserved.

The oldest Neanderthal remains, believed to between 230,000 and 300,000 years old, come from the bottom of a 160 foot shaft in Sierra de Atapurca in northern Spain. The remains can not be precisely dated so scientists have based their age estimate because their faces have "pre-Neanderthal" features. There is some debate as to whether they are Neanderthals or archaic homo sapiens or “Homo heidelbergensis”. See Homo heidelbergensis.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthals in the Levant: Behavioural Organization and the Beginnings of Human Modernity” by Donald O. Henry Amazon.com;

“The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science Is Rewriting Their Story”

by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body”

by Steven Mithen (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature” by Ludovic Slimak Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

When Neanderthal’s Lived

Neanderthals are believed to have lived between roughly 350,000 and 30,000 years ago, occupying an area that extended from Portugal in the west and central Asia in the east. They lived both in the interglacial and the glacial periods. After an ice age that covered half of Europe in glaciers, the interglacial period began around 130,000 years ago with a climate that was actually warmer than today’s; then, 85,000 years ago the last ice age began, ending 11,500 years ago. Neanderthal vanished from the fossil record around the time modern humans arrived in Europe.

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: Neanderthals are “a separate, shorn-off branch of our family tree. We last shared an ancestor at some point between 500,000 and 750,000 years ago. Then our evolutionary trajectory split. We evolved in Africa, while the Neanderthals would live in Europe and Asia for 300,000 years. Or as little as 60,000 years. It depends whom you ask. It always does... What is clearer is that roughly 40,000 years ago, just as our own lineage expanded from Africa and took over Eurasia, the Neanderthals disappeared. Scientists have always assumed that the timing wasn’t coincidental. Maybe we used our superior intellects to outcompete the Neanderthals for resources; maybe we clubbed them all to death. Whatever the mechanism of this so-called replacement, it seemed to imply that our kind was somehow better than their kind. We’re still here, after all, and their path ended as soon as we crossed paths. [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017]

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: Neanderthals are “a separate, shorn-off branch of our family tree. We last shared an ancestor at some point between 500,000 and 750,000 years ago. Then our evolutionary trajectory split. We evolved in Africa, while the Neanderthals would live in Europe and Asia for 300,000 years. Or as little as 60,000 years. It depends whom you ask. It always does... What is clearer is that roughly 40,000 years ago, just as our own lineage expanded from Africa and took over Eurasia, the Neanderthals disappeared. Scientists have always assumed that the timing wasn’t coincidental. Maybe we used our superior intellects to outcompete the Neanderthals for resources; maybe we clubbed them all to death. Whatever the mechanism of this so-called replacement, it seemed to imply that our kind was somehow better than their kind. We’re still here, after all, and their path ended as soon as we crossed paths. [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017]

Some scientists divide Neanderthals into three subcategories: 1) early or pre-Neanderthals who lived between 430,000 and 130,000 years ago, followed by the classic Neanderthals who lived from 130,000 to 47,000 years ago, then the late Neanderthals who lived between 47,000 to 28,000 years ago.

Neanderthal Timeline:

250,000 years ago — The first Neanderthals appear in Europe.

300,000 years ago — The first modern humans appear in Africa.

70,000 to 60,000 years ago — the first major wave of modern humans leave Africa.

50,000 to 60,000 years ago — Modern humans and Neanderthals share territory in Middle East.

45,000 years — Modern humans enter Europe in significant numbers.

Earliest Evidence of Neanderthals

The oldest potential Neanderthal bones date to 430,000 years ago, but the classification of these remains from Israel and France is uncertain. Neanderthals are known from numerous fossils, especially from after 130,000 years ago.

Tautavel Man refers to the archaic humans which — from approximately 550,000 to 400,000 years ago—inhabited the Caune de l’Arago, a limestone cave in Tautavel, France. The fossils found here are generally classified as homo erectus but some consider them pre-Neanderthal. Some fossils found in Israel and elsewhere dating to around the same period have tentatively been labeled as Homo heidelbergensis but are also seen as pre-Neanderthal.

The Saccopastore skulls refers to two fossil crania were discovered in a quarry in gravel and sand beds along the Aniene River Valley of Northern Rome, Italy in 1929 and 1935. In 2015, the fossils were re-dated and found to be much older than previously thought. The 2015 study estimated the fossils to be around 250,000 years old, pushing back their age by over 100,000 years and thus surpassing Altamura Man as the earliest evidence for Neanderthals in Italy. [Source: Wikipedia]

La Cotte à la Chèvre, a small cave near Grosnez on the north coast of Jersey, a small island between Britain and France that was connect by land bridges to the European continent during the ice ages. Some experts say the site suggests that Neanderthals lived and hunted in Jersey 250,000 years ago. [Source: BBC, April 8, 2023]

Paleolithic Period

Neanderthals like modern humans and homo erectus in the Paleolithic Period (about 3 million years to 10,000 B.C.). This period — also spelled Palaeolithic Period and also called Old Stone Age — is a cultural stage of human development, characterized by the use of chipped stone tools. The Paleolithic Period is divided into three period: 1) Lower Paleolithic Period (2,580,000 to 200,000 years ago); 2) Middle Paleolithic Period (about 200,000 years ago to about 40,000 years ago); 3) Upper Paleolithic Period (beginning about 40,000 years ago). The three subdivisions are generally defined by the types of tools used — and their corresponding levels of sophistication — in each period. The period is studied through archaeology, the biological sciences, and even metaphysical studies including theology. Archaeology supplies sufficient information to provide some insight into the minds of Neanderthals and early Modern Humans (i.e. Cro Magnon Man) who lived during this time.

wooly mammoths were plentiful when Neanderthals lived

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica: “The onset of the Paleolithic Period has traditionally coincided with the first evidence of tool construction and use by Homo some 2.58 million years ago, near the beginning of the Pleistocene Epoch (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago). In 2015, however, researchers excavating a dry riverbed near Kenya’s Lake Turkana discovered primitive stone tools embedded in rocks dating to 3.3 million years ago—the middle of the Pliocene Epoch (some 5.3 million to 2.58 million years ago). Those tools predate the oldest confirmed specimens of Homo by almost 1 million years, which raises the possibility that toolmaking originated with Australopithecus or its contemporaries and that the timing of the onset of this cultural stage should be reevaluated. “Throughout the Paleolithic, humans were food gatherers, depending for their subsistence on hunting wild animals and birds, fishing, and collecting wild fruits, nuts, and berries. The artifactual record of this exceedingly long interval is very incomplete; it can be studied from such imperishable objects of now-extinct culture. [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica ^]

“At sites dating from the Lower Paleolithic Period (2,580,000 to 200,000 years ago), simple pebble tools have been found in association with the remains of what may have been some of the earliest human ancestors. A somewhat more-sophisticated Lower Paleolithic tradition known as the Chopper chopping-tool industry is widely distributed in the Eastern Hemisphere and tradition is thought to have been the work of the hominin species named Homo erectus. It is believed that H. erectus probably made tools of wood and bone, although no such fossil tools have yet been found, as well as of stone.^

“About 700,000 years ago a new Lower Paleolithic tool, the hand ax, appeared. The earliest European hand axes are assigned to the Abbevillian industry, which developed in northern France in the valley of the Somme River; a later, more-refined hand-ax tradition is seen in the Acheulean industry, evidence of which has been found in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Some of the earliest known hand axes were found at Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) in association with remains of H. erectus. Alongside the hand-ax tradition there developed a distinct and very different stone tool industry, based on flakes of stone: special tools were made from worked (carefully shaped) flakes of flint. In Europe the Clactonian industry is one example of a flake tradition. ^

“The early flake industries probably contributed to the development of the Middle Paleolithic flake tools of the Mousterian industry, which is associated with the remains of Neanderthals. Other items dating to the Middle Paleolithic are shell beads found in both North and South Africa. In Taforalt, Morocco, the beads were dated to approximately 82,000 years ago, and other, younger examples were encountered in Blombos Cave, Blombosfontein Nature Reserve, on the southern coast of South Africa. Experts determined that the patterns of wear seem to indicate that some of these shells were suspended, some were engraved, and examples from both sites were covered with red ochre. [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica ^]

Ice Age Europe

Ice Ages

Neanderthals and early modern humans lived at a time when Ice Ages were shaping the climate and landscape of the places they lived in Europe and elsewhere. I Ice Ages are periods of time when huge continental glaciers (sheets of ice) have crept down from the Arctic and covered much of North America and Europe. The Pleistocene Age, which lasted from 2.6-2.3 million to 11,700 years ago, is regarded as an ice age, within which there were glacial periods, which many people think of ice ages, when glaciers grew and shrunk during different periods. The first Ice Age glaciers began appearing long ago. Large glaciers have covered landmasses for millions of years at different times before the Pleistocene Age.

There has been at least five major ice ages. The first one occurred about 2 billion years ago and lasted about 300 million years. The most recent one started about 2.6 million years ago, and technically is still going on. Denise Su wrote: When most people talk about the “ice age,” they are usually referring to the last glacial period, which began about 115,000 years ago and ended about 11,000 years ago with the start of the current interglacial period. During that time, the planet was much cooler than it is now. At its peak, when ice sheets covered most of North America, the average global temperature was about 46 degrees Fahrenheit (8 degrees Celsius). That’s 11 degrees F (6 degrees C) cooler than the global annual average today. That difference might not sound like a lot, but it resulted in most of North America and Eurasia being covered in ice sheets. Earth was also much drier, and sea level was much lower, since most of the Earth’s water was trapped in the ice sheets. Steppes, or dry grassy plains, were common. So were savannas, or warmer grassy plains, and deserts. [Source: Denise Su, Associate Professor, Arizona State University, The Conversation, June 27, 2022]

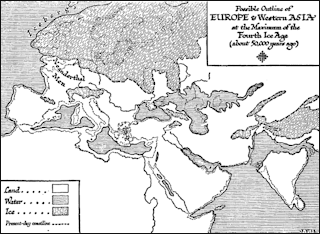

The four main glacial periods ("ice ages") are (the names refer to the southern limit of the glaciers in Europe and, in parentheses, the United States): 1) the Günz (known in the U.S. as the Nebraskan) occurred around 2 million years ago); 2) the Mindel (known in the U.S. as the Kansan) occurred around 1.25 million years ago); 3) the Riss (known in the U.S. as the Illinoisian) occurred around 500,000 years ago); and 4) the Würm (known in the U.S. as the Wisconsin) occurred around 100,000 years ago).

See Separate Article ICE AGES AND ICE AGE GLACIERS factsanddetails.com

Last Glacial Period (Ice Age)

Europe's 4th Ice Age Around 125,000 years ago, in the middle of major warm, interglacial period, sea levels were 20 to 30 feet higher than they are today. Areas of Africa, the Middle East and West Asia that are desert today were covered by tropical deciduous forests and savanna dotted with numerous lakes.

After that the climate began getting colder. By around 100,000 years a new Ice Age had begun. About 65,000 years, in the middle of the ice age, glaciers covered nearly 17 million square miles, including much of northern Europe and Canada, and sea levels were more than 400 feet lower that they are today. Many islands and land masses that are now separated by ocean water were connected by land bridges. Among the land masses that were connected were Australia and Indonesia, and Alaska and Siberia.

Around 40,000 years ago glaciers began to melt. At that time they still covered most of Britain and extended into Europe as far south as Germany. By around 17,000 years ago they had retreated from Germany. Around 13,000 they had retreated from Sweden. The Ice Age officially ended about 10,000 years ago.

The landscape of Europe was covered by ice. But it was also altered in other ways not directly related to the ice. As the glaciers moved southward, for example, forests were replaced with tundra and steppe.

During the last ice age Europe was covered mostly by open steppe which is an ideal habitat for grazing animals like horses, rhinos, deer, mammoth, reindeer and bison. Vast herds of these animals, fed on steppe grasses, roamed across Europe and Asia. As the Ice Ages ended and the climate warmed up, the habitant for the large animals herds declined as the grasslands were replaced by birch and evergreen forests.

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: “Among ecologists, the prevailing view of Europe in its natural, which is to say pre-agrarian, state is that it was heavily forested. (The continent’s last stands of old-growth forest are found on the border of Poland and Belarus, in the Bialowieza Forest, which the author Alan Weisman has described as a “relic of what once stretched east to Siberia and west to Ireland.”)” An ecologist named Frans “Vera argues that, even before Europeans figured out how to farm, the continent was more of a parklike landscape, with large expanses of open meadow. It was kept this way, he maintains, by large herds of herbivores—aurochs, red deer, tarpans, and European bison. (The bison, also known as wisents, were hunted nearly to extinction by the late eighteen-hundreds.) [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker , December 24 & 31, 2012 ||*||]

“Vera has written up his argument in a dense, five-hundred-page treatise that has received a good deal of attention from European naturalists, not all of it favorable. A botany professor at Dublin’s Trinity College, Fraser Mitchell, has written that an analysis of ancient pollen “forces the rejection of Vera’s hypothesis.” Vera, for his part, rejects the rejection, arguing that, precisely because they ate so much grass, the aurochs and the wisents skewed the pollen record. “That is a scientific debate that is still going on,” he told me.”

Neanderthals in the Middle East

Neanderthals lived in Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Palestine, Iraq, and Iran — the southernmost area of the known Neanderthal range. Their arrival in Asia is not well-dated. Around 100,000 years ago, Homo sapiens immigrants appear to have replaced them in one of the first expansions of modern humans out of Africa. In turn, starting around 80,000 years ago, Neanderthals appear to have replaced Homo sapiens in the Middle East. They inhabited the region until about 55,000 years ago. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ann Gibbons wrote in Science: Researchers have long known the Middle East was a busy crossroads for modern humans and Neanderthals. Although fossils of modern humans in Israel date back 130,000 years, recognizable Neanderthals don't show up in the fossil record of the region until about 60,000 to 70,000 years ago. Both fossils and ancient DNA have suggested Neanderthals arose more than 400,000 years ago in Europe and spread later into the Middle East, where they likely met and mated with modern humans who had migrated out of Africa. [Source: Ann Gibbons, Science, June 24, 2021]

Neanderthal sites in the Middle East that have yielded skeletal remains including1) Karain in Turkey; 2) Ksâr 'Akil and El Masloukh in Lebanon; 3) Kebara, Tabun, Ein Qashish, Shovakh, Shuqba. and Amud in Palestine-Israel; Dederiyeh in Syria; Shanidar in Iraq and Bisitun and Wezmeh in Iran. Remains in Turkey, Lebanon, and Iran are fragmentary. No Neanderthal skeletal remains have ever been found to the south of Jerusalem. There are Middle Palaeolithic Levallois points in Jordan and in the Arabian peninsula, it is unclear whether these were made by Neanderthals or modern humans. No attempt at extracting DNA from Southwest Asian Neanderthals has ever been successful.

One of the southernmost Neanderthals is a fossil from Tabun Cave, Israel, dated to 120.000-50.000 B.C.. Other known hominin fossils in Southwest Asia older than 100,000 include Shanidar 2 and 4, as well as Tabun C1. All three have at one point been classified as Neanderthals, although the latter two are now usually called pre-Neanderthals. In part because none are well-dated these attributions have all been challenged.

A modern human skull found in Manot Cave in western Galilee in northern Israel is thought to be from 55,000-year-old female. Skeletons of Neanderthals from the same time have been recovered from Amud cave 40 kilometers (24 miles) to the east of Manot cave, and from Kebara cave 50 kilometers (30 miles) to the south. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, January 28, 2015 |=|]

See Shanidar Cave in FAMOUS NEANDERTHAL SITES factsanddetails.com

Primitive Neanderthal with Modern Tools in Israel

In June 2021, scientists announced the discovery of fossils of a primitive-looking, probable Neanderthal with a relatively modern set of tools dated to 120,000 to 140,000 years ago. Finding modern tools with such a primitive-looking toolmaker at this time in the main passage between Africa and Eurasia makes this "a major discovery," writes paleoanthropologist Marta Mirazón Lahr of the University of Cambridge in an accompanying commentary. [Source: Ann Gibbons, Science, June 24, 2021]

Ann Gibbons wrote in Science: The new fossils and tools were found over the past few years in a sinkhole in a limestone quarry in central Israel, after a construction crew uncovered the first tools from the site in 2010. Over the next 5 years, a team led by archaeologist Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem excavated the open-air site at Nesher Ramla and found pieces of an ancient skull, a nearly complete jawbone, and a molar, all likely from the same individual. They also dug up animal bones and flint tools from the same layer of sediments, which date to 120,000 to 140,000 years ago, according to one of two papers published today in Science.

The stone tools were made with a so-called Levallois method: typical of the area's modern humans, as well as of Neanderthals who appeared later in the region. But the fossils were clearly not Homo sapiens, says Tel Aviv University paleoanthropologist Hila May. And they didn't look like early or late Neanderthals in the Middle East or Europe, says co-author María Martinón-Torres, a paleoanthropologist at CENIEH, the national center for research on human evolution. "They didn't fit with anything," she says.

Instead, the fossils show a "weird" mix of archaic and Neanderthal-like traits, May says. For example, the robust jaw and molar were similar to Neanderthals, but the parietal skull bones were thicker, and more like those in archaic members of Homo, May says. Dental anthropologist Rachel Sarig, also at Tel Aviv University, says the inner structure of the molars reminds her of the teeth of archaic members of the Homo genus found at Qesem Cave in Israel, dating to about 400,000 years ago. This suggests the fossils belonged to the "late survivors" of a previously unknown population of Homo, or to another Neanderthal lineage that lived in the Middle East. They could have also belonged to a hybrid who was a mix of Neanderthal and archaic Homo, says paleoanthropologist Israel Hershkovitz of Tel Aviv University, which would add another member to the diverse cast of hominins that ranged across Eurasia and Africa during the Middle Pleistocene, some 790,000 to 130,000 years ago.

Neanderthals in Central Asia

Teshik-Task from Uzbekistan

The easternmost remains of a Neanderthal — the Teshik-Tash child — were found in Man-Kuan cave near Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Dated to between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago, the fossils are the oldest known hominid remains in Central Asia. Belonging to a Neanderthal child, estimated to be nine or ten years old, they were discovered in 1938 by A.P. Okladnikov in Teshik-Tash – a cave situated in the branches of the Hissar Range south of Samarkand, Uzbekistan, about 1500 meters above sea level. [Source: Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Erhnography ^=^]

Middle Paleolithic (Mousterian) tools and numerous bones of wild goats and other animals were found in the cave deposits. It appears that people living in the grotto mostly hunted mountain goats. Horns of goats, arranged pairwise, were found around the skeleton. They might have been placed intentionally (some, judging by their position, had been stuck into the ground). If so, rather than merely abandoning the bodies of their dead, the Neanderthals buried them according to a rite reflecting some ideas of the other world. ^=^

There was initially some debate as to whether the fossils belonged to a “classical” Neanderthal” or “an evolutionary line leading to anatomically modern humans. The structure of DNA extracted from the bones of the Teshik-Tash child links him with Neanderthals rather than with Homo sapiens. The famed Russian scientist M.M. Gerasimov has reconstructed the complete appearance of the Teshik-Tash child. The skull, in his words, “is much larger and heavier than that of a modern child of the same age. The browridge is much more robust than in a modern adult. The forehead is retreating . The head is large and heavy, especially in the facial part, the stature is low, and the trunk is long. While being 9-10, he looks older. The disproportion between the head and the rest of the body combines with very powerful shoulders and a peculiarly stooped trunk. The arms are very strong. The legs are short and muscular. This trait combination is typical of Neanderthals.” ^=^

A fossilized tooth found decades ago in the Zagros Mountains first identified as belong to modern humans it turns out belongs to a Neanderthal child who lived between 70,000 and 40,000 years ago. A reexamination in the late 2010s using modern techniques established the new dating and identification. The researchers said it was is the first evidence that Neanderthals once lived in this area of present-day Iran. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2019]

Neanderthals in Russia and Siberia

Neanderthals reached the Russian plain around 120,000 years ago. They reached sites as far north as 52 degrees north. During the last ice age Neanderthals retreated to the Crimean peninsula and the Caucasus Mountains. They are believed to have disappeared from the area between 25,000 and 30,000 years ago (that is when the disappeared from the Iberian peninsula).

Well-preserved Neanderthals have been found in Mezmaiskaya in Russia Neanderthals lived mainly in Europe and migrated as far south as Israel and Spain during the ice ages. Flourishing in a relatively cold ice-age climate for 200,000 years, they lived in Europe at that time when it was covered by woods and grasslands that supported large herds of horses, reindeer, bison and species adapted for cold weather. Scientists theorize that the Neanderthals arrived from a place with a warm climate, perhaps migrating south during the winter until they adapted to the colder climate.

Archaeology magazine reported: The first known family of Neanderthals was identified by researchers who sequenced the DNA of 11 individuals from Chagyrskaya Cave in southern Siberia. The small group likely lived together 54,000 years ago. The genetic analysis determined that 2 of the cave’s inhabitants were a father and his teenage daughter, the first time such a relationship between Neanderthals has been established. The study also concluded that 2 other adult males, an adult female, and a small boy were part of their extended family. [Source: Archaeology Magazine, January 2023]

University of Valencia researchers discovered that Neanderthals reached all the way to the Altai Mountains where, Siberia, Mongolia and Kazakhstan all cone together. Here Neanderthals interacted with with their enigmatic Asian cousins, the Denisovans, in a regions consisting of mountains and Siberian forest steppe, which is drier and colder than their western counterparts.. [Source: Asociacion RUVID, phys.org, Ancientfoods June 10, 2021]

Neanderthal remains dated to 60,000 to 50,000 years ago BP from the site of Chagyrskaya in the Altai Mountains in Southern Siberia, located just 100 kilometers from the Denisova Cave. “The steppe lowlands of the Altai Mountains were suitable for the habitation of the Neanderthals 60,000 years ago. Despite the sparse vegetation and its seasonal nature, the absence of tundra elements and relatively mild climate allowed eastern Neanderthals to keep the same food strategies as their western relatives,” says Natalia Rudaya, head of PaleoData Lab of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography Siberian Branch Russian Academy of Science.

According to Archaeology magazine: “Max Planck Institute scientists sequenced the genome of a second individual who lived at Denisova more than 50,000 years ago. They discovered that the individual was actually a Neanderthal, not a Denisovan. It is the most complete Neanderthal genome yet recovered, and it has given geneticists a novel point of comparison among various human lineages. The new analysis shows that occasional interbreeding between Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo sapiens probably took place in more than one time and place, and that the Denisovans also interbred with an unknown archaic hominin group — possibly Homo heidelbergensis.[Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2014]

Siberian Neanderthals Ate Both Plants and Animals, See NEANDERTHAL FOOD AND DIET factsanddetails.com ; and Denisova Cave in FAMOUS NEANDERTHAL SITES factsanddetails.com

Neanderthal sites

Neanderthals In the Arctic?

Evidence of Neanderthal has been found near the Arctic Circle in the Ural mountains of Russia. Archaeology magazine reported: In the northern Ural Mountains, archaeologists have discovered Mousterian stone tools and butchered mammoth bones, which are associated with Neanderthals in Europe (though modern humans in southwest Asia used similar technology). The artifacts are dated to 28,500 years ago, 8,000 years after Neanderthals are thought to have disappeared, suggesting that some mastered living in cold environments and held on long after modern humans had usurped the rest of their range. The research was published in Science in May 13, 2011. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2011]

AFP reported: “The French, Russian and Norwegian researchers discovered more than 300 stone tools and the remains of several mammals, including mammoths, black bears and woolly rhinos that appear to have been butchered. The remains were unearthed during several excavations at the Byzovaya site in the foothills of the Urals on the right bank of the Pechora River. In addition to radiocarbon dating, the researchers used a technique known as optically stimulated luminescence, which allows them to tell when sediment has been exposed to light for the last time. [Source: AFP, May 12, 2011 ]

While Neanderthal Man occupied Eurasia at lower latitudes, Byzovaya could have been their last Nordic refuge before their extinction, according to the study's authors. Until now, Neanderthal remains have all come from areas at least 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) south of Byzovaya. The objects discovered at Byzovaya, which appears to have been occupied just once in 3,000 years, belong to the Mousterian tool tradition used by Neanderthal Man, according to the authors. This culture developed during the Middle Paleolithic era in Eurasia 300,000 to 37,000 years ago and is distinguished by a wide range of stone tools.

Dan McLerran wrote in Popular Archaeology: “While excavating at Byzovaya, Russia, an archaeological site in the cold western foothills of the Ural Mountains at the edge of the Arctic Circle, Dr. Ludovic Slimak of the Université de Toulouse le Mirail, France, along with a team of colleagues, had unearthed a total of 313 human artifacts, along with a massive accumulation of remains of mammoths and other animals, (such as reindeer, wooly rhinoceros, musk ox, horse, wolf, polar fox, and bear). Examination of the mammoth remains indicated that they had been butchered using human-made tools. But these artifacts, a stone tool technology known as Mousterian and associated most commonly with Neanderthals, were dated to about 28,500 BP, too late for the Neanderthals. The dating didn't seem to match the nature of the technology, as the newly discovered artifacts defined a toolkit that belonged primarily to the Middle Paleolithic period (300,000 to 40,000 years ago), and Neanderthals are generally thought to have become extinct after that time period — replaced, as many scientists have suggested, by Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) around 75,000 to 50,000 years ago with a more advanced stone tool industry. [Source: Dan McLerran, Popular Archaeology, May 12, 2011 -]

Neanderthals in California, 130,000 Years Ago?

In 2017, scientists made the startling claim that the first known Americans arrived more than 115,000 years than they earlier thought — and maybe they were Neanderthals. Associated Press reported: “Researchers say a site in Southern California shows evidence of humanlike behavior from about 130,000 years ago, when bones and teeth of an elephantlike mastodon were evidently smashed with rocks. [Source: Associated Press, April 26, 2017~||~]

“The earlier date means the bone-smashers were not necessarily members of our own species, Homo sapiens. The researchers speculate that these early Californians could have instead been species known only from fossils in Europe, Africa and Asia: Neanderthals, a little-known group called Denisovans, or another human forerunner named Homo erectus. “The very honest answer is, we don’t know,” said Steven Holen, lead author of the paper and director of the nonprofit Center for American Paleolithic Research in Hot Springs, South Dakota. No remains of any individuals were found. ~||~

“Whoever they were, they could have arrived by land or sea. They might have come from Asia via the Beringea land bridge that used to connect Siberia to Alaska, or maybe come across by watercraft along the Beringea coast or across open water to North America, before turning southward to California, Holen said in a telephone interview. Holen and others presented their evidence in a paper released by the journal Nature . Not surprisingly, the report was met by skepticism from other experts who don’t think there is enough proof. ~||~

“The research dates back to the winter of 1992-3. The site was unearthed during a routine dig by researchers during a freeway expansion project in San Diego. Analysis of the find was delayed to assemble the right expertise, said Tom Demere, curator of paleontology at the San Diego Natural History Museum, another author of the paper. ~||~

“The Nature analysis focuses on remains from a single mastodon, and five stones found nearby. The mastodon’s bones and teeth were evidently placed on two stones used as anvils and smashed with three stone hammers, to get at nutritious marrow and create raw material for tools. Patterns of damage on the limb bones looked like what happened in experiments when elephant bones were smashed with rocks. And the bones and stones were found in two areas, each roughly centered on what’s thought to be an anvil. The stones measured about 8 inches (20 centimeters) to 12 inches (30 centimeters) long and weighed up to 32 pounds (14.5 kilograms). They weren’t hand-crafted tools, Demere said. The users evidently found them and brought them to the site. The excavation also found a mastodon tusk in a vertical position, extending down into older layers, which may indicate it had been jammed into the ground as a marker or to create a platform, Demere said. The fate of the visitors is not clear. Maybe they died out without leaving any descendants, he said. ~||~

“Experts not connected with the study provided a range of reactions. “If the results stand up to further scrutiny, this does indeed change everything we thought we knew,” said Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London. Neanderthals and Denisovans are the most likely identities of the visitors, he said. But “many of us will want to see supporting evidence of this ancient occupation from other sites, before we abandon the conventional model of a first arrival by modern humans within the last 15,000 years,” he wrote in an email. Erella Hovers of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University in Tempe, who wrote a commentary accompanying the work, said in an email that the archaeological interpretation seemed convincing. Some other experts said the age estimate appears sound. ~||~

“But some were skeptical that the rocks were really used as tools. Vance Holliday of the University of Arizona in Tucson said the paper shows the bones could have been broken the way the authors assert, but they haven’t demonstrated that’s the only way. Richard Potts of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, said he doesn’t reject the paper’s claims outright, but he finds the evidence “not yet solid.” For one thing, the dig turned up no basic stone cutting tools or evidence of butchery or the use of fire, as one might expect from Homo sapiens or our close evolutionary relatives.” ~||~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024