Home | Category: First Hominins in Europe / First Modern Humans

HOMO HEIDELBERGENSIS

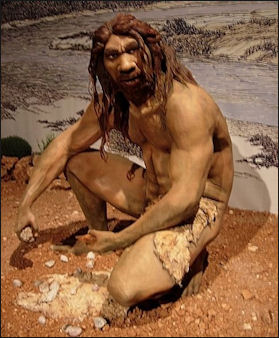

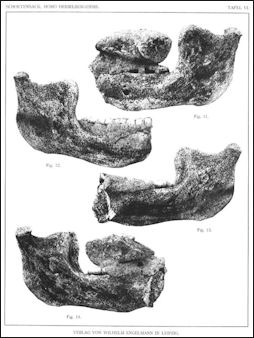

Homo Heidelbergensis Homo heidelbergensis (hy-dil-ber-GEN-sis) is a species of “Homo” named after a 500,000-year-old jawbone found in 1907 near Heidelberg, Germany that some scientists believe evolved into Neanderthals. Its tools included the Acheulan hand ax.

Some scientists believe that all their hominin remains found in Europe come from three species: “Homo erectus “, “Homo sapiens” and Neanderthals. Others believe that the “Homo “ tree is much more complex. They say other species such as “Homo heidelbergensis” and perhaps other hominin species not yet discovered may have existed as well.

Homo heidelbergensis was the first early human species to live in colder climates. It lived at the time of the oldest definite control of fire and use of wooden spears, and it was the first early human species to routinely hunt large animals. It was also the first species to build shelters, creating simple dwellings out of wood and rock. [Source: Smithsonian]

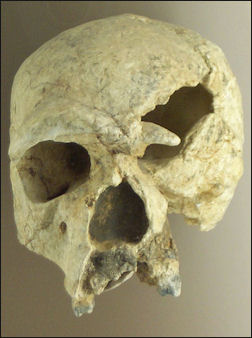

Homo heidelbergensis was discovered In 1908 near Heidelberg, Germany by a workman in the Rösch sandpit just north of the village of Mauer. The workman found a of nearly complete mandible (jawbone) except for the missing premolars and first two left molars. German scientist Otto Schoentensack was the first to describe the specimen and proposed the species name Homo heidelbergensis. Before the naming of this species, scientists referred to early human fossils showing traits similar to both Homo erectus and modern humans as ‘archaic’ Homo sapiens.

Geologic Age: 700,000 to 200,000 years ago, Size: males: 1.7 meters (5 feet 7 inches), 57 kilograms (125 pounds); females: 1.57 meters (5 feet 2 inches), 51 kilograms (112 pounds). Skull Features: large mandible, no chin, a very large browridge, and a larger braincase and flatter face than older early human species; Brain size: 1,200 cubic centimeters ( comparable to modern humans.); Body Features: Similar to modern humans but wider and more heavily built. Their relatively short, wide bodies were likely an adaptation to conserving heat. Discovery Sites: Europe; possibly Asia (China); Africa (eastern and southern). Heidelberg, Germany is the most famous discovery site and the source of its name

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“In search of Homo heidelbergensis: How Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and hobbits emerged by Christopher Seddon Amazon.com;

“European Origin of Homo Sapiens: Atapuerca” by Santiago Sevilla Amazon.com

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“The Earliest Europeans: A Year in the Life: Survival Strategies in the Lower Palaeolithic (Oxbow Insights in Archaeology) by Robert Hosfield (2020) Amazon.com;

“Earliest Italy: An Overview of the Italian Paleolithic and Mesolithic by Margherita Mussi Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

Archaic Homo Sapiens

Homo heidelbergensis is regarded as an Archaic Homo sapien. Archaic Homo sapiens is term used to describe hominins viewed as transitions between Homo erectus and modern man, and possibly Neanderthals too. These creatures came on the scene when big browed, jutting jaw hominins were still around. Homo sapien means "Wise Man."

Geologic Age: Variable estimates, ranging between 100,000 to 750,000 years. Most scientists believe modern man originated in Africa between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago. A 260,000-year-old Florisbad skull from South Africa had pronounced browridges but less of than its predecessors and was more like the brow of modern humans.

Size: males: 1.75 meters (5 feet 9 inches), 62 kilograms (137 pounds); females: 1.57 meters (5 feet 2 inches), 51 kilograms (112 pounds). Skull Features: bony chin and high forehead typical of modern humans but bigger face, weaker chin and a protruding browridge above the eyes. Body Features: Basically modern but more ruggedly built.

Discovery Sites: Found in Asia, Europe and Africa but not America and Australia. Most complete skull found in 1960 in Petralona, Greece by Greek villagers. Skull housed in Paleontological Museum, University of Thessaloniki. Good fossils also found in Zambia. [Source: Kenneth Weaver, National Geographic, November 1985 [┹]

José María Bermúdez de Castro at the National Research Centre on Human Evolution in Burgos, Spain told New Scientist that there is indirect evidence that hominins arrive in Europe more than 1,2 million years ago: “[Stone tools from] Pirro Nord in Italy may be older than Sima del Elefante,” dated to 1.1 million years old. “Likewise, the Barranco León and Fuente Nueva 3 Spanish sites have yielded stone tools probably 1.3 million years old.” [Source: Colin Barras, New Scientist, March 26, 2008]

Homo Heidelbergensis More Closely Related to Denisovans Than Neanderthals

Homo Heidelbergensis Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The story of this new work begins in northern Spain. There, a group of Spanish researchers at the site of Sima de los Huesos teamed up with geneticists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology to examine the oldest known hominin DNA sample, which comes from a 400,000-year-old Homo heidelbergensis thigh bone. They sequenced the bone’s mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is passed from mother to child. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2014]

“What we were expecting to see was Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA,” says Matthias Meyer of the Max Planck Institute, as Neanderthals would later occupy that part of Europe and might be expected to carry genetic material from the previous inhabitants. Surprisingly, the mtDNA is instead more closely related to that of a hominin who lived more than 50,000 years ago in Siberia’s Denisova Cave than it is to that of Neanderthals. The Denisovans were related to, but genetically distinct from, Neanderthals.

“According to Meyer, the Sima de los Huesos sample is old enough that it could represent an ancestor to both Denisovans and Neanderthals. However, it is also possible that Homo heidelbergensis is not ancestral to either group, but later interbred with the Denisovan lineage. Studies of nuclear DNA, which contains genetic information from both parents, will be needed to clarify the relationship, Meyer believes.

Life of Homo Heidelbergensis

According to the Smithsonian: There is evidence that H. heidelbergensis was capable of controlling fire by building hearths, or early fireplaces, by 790,000 years ago in the form of fire-altered tools and burnt wood at the site of Gesher Benot Ya-aqov in Israel. Why did they come together at these early hearths? Perhaps to socialize, to find comfort and warmth, to share food and information, and to find safety from predators. But despite living in colder climates, evidence of fire is minimal in the archaeological record until 400,000 to 300,000 years ago. Though it is possible fire remnants simply degraded.

In Europe, evidence of constructed dwellings — defined as firm surface huts with solid foundations built in areas mostly sheltered from the weather — goes way back in time. The earliest example is a 700,000-year-old stone foundation from Přezletice, Czech Republic. This dwelling probably featured a vaulted roof made of thick branches or thin poles, supported by a foundation of big rocks and earth. Other such dwellings have been postulated to have existed in in Bilzingsleben, Germany; Terra Amata, France; and Fermanville and Saint-Germain-des-Vaux in Normandy. Probably occupied during the winter, they were very small, averaging only 3.5 meters × 3 meters (11.5 feet × 9.8 fet) in area. They were probably only used for sleeping in, while other activities (including firekeeping) seem to have been done outside. Less-permanent tent technology may have been present in Europe in the Lower Paleolithic. [Source: Wikipedia]

H. heidelbergensis was also the first hunter of large game animals; remains of animals such as wild deer, horses, elephants, hippos, and rhinos with butchery marks on their bones have been found together at sites with H. heidelbergensis fossils. Evidence for this also comes from 400,000 year old wooden spears found at the site of Schöningen, Germany, which were found together with stone tools and the remains of more than 10 butchered horses.

One site in Atapuerca, northern Spain, dating to about 400,000 years ago, shows evidence of what may be human ritual. Scientists have found bones of roughly 30 H. heidelbergensis individuals deliberately thrown inside a pit. The pit has been named Sima de los Huesos (‘Pit of Bones’). Alongside the skeletal remains, scientists uncovered a single well-made symmetrical handaxe —illustrating the tool-making ability of H. heidelbergensis.

See Separate Article: HOMO ERECTUS LIFE, STRUCTURES, LANGUAGE, ART AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

700,000-Year-Old Homo Heidelbergensis Footprints from Ethiopia

Footprints left by children as young as 12 months found un Ethiopia and belong to an archaic homo sapien, perhaps Homo heidelbergensis, offer a glimpse of family dynamics 700,000 years ago. The prints at Melka Kunture were left by a group individuals gathered around a shallow pool, where evidence of stone tool knapping and the butchered carcass of a hippopotamus were also found. The small children’s footprints reveal how they tagged along as the adults carried out their daily activities, perhaps to observe and learn important survival skills such as hunting and toolmaking. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

Live Science reported: a 2018 study in the journal Scientific Reports documented a collection of human footprints and animal tracks was unearthed between 2013 and 2015 at a 700,000-year-old archeological site in Ethiopia called Melka Kunture. There, a cluster of tracks belonging to 11 adults and children potentially as young as 12 months old suggested that children were present when tools were made and animals butchered. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 17, 2023]

"Children and adult footprints were found on the border of a pond where other animals congregated and where hippos were butchered by hominins, suggesting that children were assisting adults and learning since their first years how to survive in the then wild environment," said Flavio Altamura, an archeologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany, who co-authored the 2018 study of the Ethiopian fossils.

300,000-Year-Old Homo Heidelbergensis Footprints Found with Those of Rhinos and Giant Elephants

Footprints belonging to Homo heidelbergensis adults and children were found at a site in Lower Saxony, Germany, called Schöningen, that was once on the shores of a lake where giant elephants, rhinos and other prehistoric beasts gathered to drink. Live Science reported: Three rare, 300,000-year-old footprints from a fossil site in northwestern Germany reveal that Homo heidelbergensis co-existed with prehistoric elephants and rhinos, whose footprints were also found at the site. This is the first footprint evidence of H. heidelbergensis from Germany and only the fourth record of the species' footprints worldwide. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 17, 2023]

"These three footprints represent a significant 'direct' proof of the hominin presence on the site," Altamura, the lead author of a study describing the fossils, told Live Science in an email. While one footprint clearly belonged to an adult, the others were much smaller. "Since two footprints are related to young individuals, this is also proof of the existence of children on the spot," Altamura said.

_01.jpg)

Homo Heidelbergensis The discovery is remarkable because signs of children at prehistoric sites are scarce. Most of the evidence researchers have about the earliest periods of humanity comes from tools, human remains and food waste in the form of animal bones, Altamura explained. "You have to look for children's bones, that are very rare, and it is very hard to link tools and food waste with children's activity. So it is very difficult to say something about their behavior and the kind of life they were [leading]. The newly found footprints provide clues about what it was like to be a child 300,000 years ago. "This is a rare snapshot of childhood in prehistory,

The footprints reveal aspects of our human relatives' daily lives, which researchers describe in a study published May 12 in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews. The findings show that long-extinct "Heidelberg people" dwelled on the shores of an ancient lake among herds of the largest land animals at the time — prehistoric elephants called Palaeoloxodon antiquus that had straight tusks and weighed up to 13 tons (12 metric tons).

The researchers also unearthed tracks belonging to a rhinoceros, which they identified as Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis or S. hemitoechus. They are the first footprints of either species ever found in Europe. The human footprints were probably left during a small family outing, Altamura said. "We may suggest that a small hominin group that included children was walking among elephants and other species on the muddy shore of an ancient lake, perhaps looking for and collecting food, or bathing, or just playing there."

Homo Heidelbergensis Evolution and Extinction

Homo heidelbergensis species may reach back to 1.3 million years ago, and include early humans from Spain (‘Homo antecessor’ fossils and archeological evidence from 800,000 to 1.3 million years old), England (archeological remains back to about 1 million years old), and Italy (from the site of Ceprano, possibly as old as 1 million years). Comparison of Neanderthal and modern human DNA suggests that the two lineages diverged from a common ancestor, most likely Homo heidelbergensis, sometime between 350,000 and 400,000 years ago — with the European branch leading to Neanderthals and the African branch (sometimes called Homo rhodesiensis) to H. sapiens.

According to research released in November 2020,, plummeting temperatures and changing rainfall may have been the "primary factor" behind the extinction of three human ancestor species: Neanderthals, Homo erectus, and Homo heidelbergensis. Business Insider reported: By examining more than 2,750 archaeological records, a team from Italy found that the climate cooled by up to 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) on average per year ahead of the species' disappearances. [Source: Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, December 12, 2020]

“As the climate changed and their preferred food sources suffered in the cold, both species of Homo lost half of their ecological niche in Africa, Asia, and Europe. Neanderthals, meanwhile, lost 25 percent, according to the study. “Even the brain powerhouse in the animal kingdom cannot survive climate change when it gets too extreme," study author Pasquale Raia, a paleontologist from the University of Naples, told ScienceAlert.

Homo Heidelbergensis and Elephant Hunting

Bones of elephants and rhinoceros and human tools, dated to 400,000 years ago, have been found by what use to be an ancient lake on the present-day route of the Chunnel rail link in Ebbsfleet, Kent southern England. The elephant weighed ten tons — making it twice the size of modern elephants. It is thought to have been brought down by spear-throwing hunters. After it was killed the elephant appears to have been butchered using flint tools and eaten raw.

More tools were found 25 meters away which implies that the ancient lake was a popular hunting ground, perhaps because it served as a water hole. No evidence of spears was found but hominins at that time did have spear technology. One can surmise that there was probably a big feast after the elephant kill. Francis Wenhan-Saith of the University of Southampton in Britain told the Times of London, “We can imagine these ancient people swarming over the elephant carcass to butcher it. The elephant was huge and it would have provided food for a lot of people — the problem would have been how much they could eat before it went off.”

A rhinoceros jawbone was found near the elephant bones. Jawbones were often removed from the carcass so the marrow could be sucked. The jawbone of the elephant was missing. The site is not that far from the site where Boxgrove Man was found. The homo species that dined on the elephant are thought to be Homo heidelbergensis like Boxgrove Man.

Homo Heidelbergensis, Language and Mass Burials

A study of fossils from “ Homo heidelbergensis” dated to 350,000 years ago indicate that it had ear bones similar to those of modern man and they were attuned to pick up the frequencies used in modern human speech. A team led by Ingacia of the University of Alcala in Spain argue that the capacity for human speech developed about 500,000 years but spoken language approaching the complexity of what were speak today did not develop until fairly recently.

The University of Alcala scientists studied the hammer, stirrup and anvil bones in the ears of a “ Homo heidelbergensis” skull found in Sima de los Huesos in the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain. They created models of the bones and then analyzed what frequencies they could hear and concluded they were especially good at discerning sounds in a range of 2 to 4 kHZ, the same as modern man ears. Chimpanzee ears by contrast are tuned to frequency peaks at 1khz and 8kHz. The reasoning behind this finding and language development goes that hominins would not have developed such sophisticated ears unless they were going to be used for sophisticated vocalizations.

Most of the 300,000-year-old remains of 27 individuals found in Sierra de Atapuerca were teenagers and young adults that had been thrown down a shaft. One of three skulls found at the site was large enough to house the brain of modern human. Perhaps, some archaeologists argue, that shaft was site of the first known ritual burial. This argument is based on the fact that the hominin s were buried together and a valuable stone ax was found with them. It has been reasoned that the ax had to have been put there for some higher purpose or why else would such valuable thing be used for no apparent functional reason. There was no wear on the ax to show it had ever been used to butcher meat or some other purpose.

500,000-Year-Old Stone Spear Tip Made by Homo Heidelbergensis?

Homo Heidelbergensis Stone spear tips thought have been made modern humans or Neanderthal are much older than previously thought — about 500,000 years old — and are so old scientists believe they may have even been created by an earlier ancestor. Malcom Ritter of Associated Press wrote: “Both Neanderthals and members of our own species, Homo sapiens, used stone tips - a significant development that made spears more effective, lethal hunting weapons. The new findings from South Africa suggest that maybe they didn't invent that technology, but inherited it from their last shared ancestor,Homo heidelbergensis. [Source: Malcom Ritter, Associated Press, December 2012 ++]

“The researchers put the date of the South African stone tips at about half-a-million years ago - 200,000 years earlier than other research has suggested. The new study involved analyzing stone points, a bit less than 3 inches long on average, that had been excavated about 30 years ago. Scientists had previously estimated they were about 500,000 years old, but it wasn't clear whether they were used as spear tips or some other kind of tool, said Jayne Wilkins, a researcher at the University of Toronto and lead author of the new report. So she and her co-authors looked for evidence that the artifacts were spear tips, focusing on the way they were shaped and fractured. The pattern of damage along their edges fit in with what researchers found when they made copies of the artifacts and thrust them into the carcasses of antelopes. ++

“From the age of the stone tips, the researchers suggest the technology may have been used by Homo heidelbergensis. Sally McBrearty, an anthropology professor at the University of Connecticut who was not involved in the study, said it's clear that the South African artifacts are spear points. She said she sees no logical reason to doubt the trove is 500,000 years old, but she said she'd like to see some firmer proof. "I would be happy to say that this is really half-a-million years old, I just want to be sure that it is," she said. There's some room for doubt because of assumptions required in the dating technique and the geology of the South African site where the points were found, she said. Further sampling and analysis could firm up the evidence for the age, she said.” ==

Alok Jha wrote in The Guardian: ““The use of spears for hunting has been dated back to at least 600,000 years ago, from sites in Germany, but the oldest spears are nothing more than sharpened sticks. The evidence for stone-tipped spears until now has been no more than 300,000 years old, from triangular stone tips found all over Africa, Europe and western Asia. "They're associated in Europe and Asia with Neanderthals and in Africa with humans and our nearest ancestors," said Wilkins. "Sometimes at these sites, they were used for other ways as well, sometimes for cutting or butchery or as knives or in processing hides or other materials."[Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, November 15, 2012 |=|]

Homo heidelbergensis used tools to hunt. Scientists have found a throwing stick measuring about 25 inches (64.5 centimeters) long presumably used by Homo heidelbergensis. Found in Germany and first reported in April 2020 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, it has been dated to be 300,000 years old and could have been used to wound or kill small prey, like rabbits, swans and ducks, according to the University of Tübingen. Homo heidelbergensis also used spears and long lances to hunt. Most of these wooden weapons are long gone, but the German site of Schöningen preserves exceptional examples of this ancient hunting tradition. [Source: LiveScience, October 12, 2023]

See First Spears Under HUNTING BY HOMININS 500,000 TO 100,000 YEARS AGO europe.factsanddetails.com

Studying the 500,000-Year-Old Stone Spear Tips

500,000-year-old spearpoints

Alok Jha wrote in The Guardian: “The invention of stone-tipped spears was a significant point in human evolution, allowing our ancestors to kill animals more efficiently and have more regular access to meat, which they would have needed to feed ever-growing brains. "It's a more effective strategy which would have allowed early humans to have more regular access to meat and high-quality foods, which is related to increases in brain size, which we do see in the archaeological record of this time," said Jayne Wilkins, an archaeologist at the University of Toronto who took part in the latest research. [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, November 15, 2012 |=|]

“The technique needed to make stone-tipped spears, called hafting, would also have required humans to think and plan ahead: hafting is a multi-step manufacturing process that requires many different materials and skill to put them together in the right way. "It's telling us they're able to collect the appropriate raw materials, they're able to manufacture the right type of stone weapons, they're able to collect wooden shafts, they're able to haft the stone tools to the wooden shaft as a composite technology," said Michael Petraglia, a professor of human evolution and prehistory at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the research. "This is telling us that we're dealing with an ancestor who is very bright." Before Homo heidelbergensis, Homo erectus was known to have used handheld stones as cutting tools. But they were not using, as far as anyone knows, spears. "This is a major innovation, getting into a new ecological niche," said Petraglia. |=|

“He added that the discovery also shed light on the development of modern human cognition. "Hominins – both Homo erectus and earlier humans – were into this meat-eating niche and meat-eating is something that is thought to be very important in terms of fuelling a bigger brain," said Petraglia. "In terms of our evolutionary history, that's been going on for millions of years. You have selection for a bigger brain and that's an expensive tissue and that protein from meat is a very important fuel, essentially. If you become a killing machine, using spears, you've come up with a technological solution where you can be reliant on meat-eating constantly. Homo heidelbergensis is known as a big-brained hominin, so having reliable access to meat-eating is important."

Murdered Homo Heidelbergensis?

Aout 430,000 years ago in northern Spain, the bodies of at least 28 Homo heidelbergensis found their way to the bottom of a 13-meter (43-foot) -deep shaft in the bedrock that archaeologists call Sima de los Huesos, or “Pit of the Bones.” Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: How the bodies got there is a mystery that Nohemi Sala, a paleoanthropologist at the Joint Center for Evolution and Human Behavior at the Institute of Health Carlos III in Madrid, has been trying to solve since 2007. Several explanations have been proposed: Carnivores might have dragged them there, or perhaps 28 separate hapless hominins accidentally fell down the shaft. In one particular case, the pit appears to have been used to dispose of the earliest known murder victim. [Source:Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

“Sala discovered the evidence of murder while studying breakage patterns of the bones — 6,700 in total. Most breaks had occurred over the millennia that the bones sat in the ground, but one skull had some very distinctive damage. Two breaks in the forehead appear to have occurred while the individual was alive. With no signs of healing, they indicate the individual did not survive long after being struck. The wounds had been made by a blunt object, and each blow was probably deadly on its own, which rules out the possibility of a hunting accident or unusual suicide attempt.

“Sala’s analysis was also important for what it did not reveal. The pit bones did not show much evidence of carnivore damage, or the type of breaks that might occur had people merely fallen in. Sala believes, instead, that Sima de los Huesos was purposefully used to dispose of the deceased, and that it may reflect the capacity of H. heidelbergensis for both violence and compassion. “They cared for the dead,” says Sala, “and this is a very human behavior.”

Homo Heidelbergensis Art

Homo heidelbergensis is generally estimated to have lived from around 600,000 years ago to 300,000 years ago. Modern humans are well known for producing etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value after this time. As of 2018, only handful of objects with postulated to have symbolic etching, predate 200,000 years ago. Among these are: 1) a 400,000 to 350,000 years old bone from Bilzingsleben, Germany; 2) three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; 3) a 250,000-year-old pebble from Markkleeberg, Germany; 4) 18 roughly 200,000-year-old pebbles from Lazaret (near Terra Amata); and 5) a roughly 200,000-year-old lithic from Grotte de l'Observatoire, Monaco. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the mid-19th century, French archaeologist Jacques Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes began excavation at St. Acheul, Amiens, France, (the area where the Acheulian was defined), and, in addition to hand axes, reported perforated sponge fossils (Porosphaera globularis) which he considered to have been decorative beads. This claim was completely ignored. In 1894, English archaeologist Worthington George Smith discovered 200 similar perforated fossils in Bedfordshire, England, and also speculated that their function was beads. In 2005, Robert Bednarik reexamined the material, and concluded that—because all the Bedfordshire P. globularis fossils are sub-spherical and range 10–18 mm (0.39–0.71 in) in diameter, despite this species having a highly variable shape—they were deliberately chosen.

Early modern humans and late Neanderthals made wide use of red ochre for presumably symbolic purposes as it produces a blood-like colour, though ochre can also have a functional medicinal application. Beyond these two species, ochre usage is recorded at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, where two red ochre lumps have been found; Ambrona where an ochre slab was trimmed down into a specific shape; and Terra Amata where 75 ochre pieces were heated to achieve a wide colour range from yellow to red-brown to red. Sima de los Huesos hominins are conspicuously associated with only a single stone tool, a carefully crafted hand axe made of high-quality quartzite (rarely used in the region). In some cases it appears these tools were purposefully and symbolically placed with the bodies as some kind of grave good. Supposed evidence of symbolic graves would not surface for another 300,000 years.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except 500,000-year-old spear heads from Scientific American

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024