Home | Category: First Hominins in Europe / First Modern Humans

FIRST HOMININS IN BRITAIN, 850,000 YEARS AGO

Homo Antecessor The earliest evidence of hominin (human ancestors) in Britain is found at Happisburgh in Norfolk, where lithic artefacts and fauna have eroded from coastal deposits. The site is dated to 850,000 years old or older. Environmental data suggesting a relatively cold climate at the time of occupation. The Happisburgh site is particularly significant as it has pushed back the estimate of human presence in Northern Europe. It is also the location of the oldest hominin footprints located outside of Africa. [Source: University College London]

Archaeologists digging on a Norfolk beach in found the flint tools that show the first humans were living in Britain much earlier than previously thought. Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: While digging along the, archaeologists discovered 78 pieces of razor-sharp flint shaped into primitive cutting and piercing tools. The stone tools were unearthed from sediments that are thought to have been laid down either 840,000 or 950,000 years ago, making them the oldest human artefacts ever found in Britain. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, July 7 2010]

Researchers led by the Natural History Museum and British Museum in London began excavating sites near Happisburgh in 2001 as part of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain project and soon discovered tools from the stone age beneath ice-age deposits. So far, though, they have found no remains of the ancient people who made them. "This would be the 'holy grail' of our work," said Stringer. "The humans who made the Happisburgh tools may well have been related to the people of similar antiquity from Atapuerca in Spain, assigned to the species Homo antecessor, or 'pioneer man'."

According to the BBC: Because of the missing fossil evidence, it is unclear what species of humans were in Happisburgh, but later remains in other parts of Europe suggest they may have been a more advanced species called Homo antecessor. The Happisburgh species of humans might have evolved into the Neanderthals, who were well established by 400,000 years ago.

In neighbouring Suffolk lies another site, Pakefield, which is dated to 700,000 years old, with fauna and environmental data suggesting a Mediterranean climate. No hominin remains have been recovered from these sites; however, the dates, human-made tools, and the size of the hominin footprints may indicate a Homo antecessor or a similar hominin (Ashton et al. 2014). [Source: University College London]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World” by Paul Pettitt, Mark White Amazon.com;

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“The Paleolithic Revolution (The First Humans and Early Civilizations)” by Paula Johanson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Paleolithic Technologies (Routledge Studies in Archaeology)”

by Steven L. Kuhn Amazon.com;

“Continuity and Discontinuity in the Peopling of Europe” by Silvana Condemi, Gerd-Christian Weniger (2011) Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala and Camilo J. Cela-Conde (2017) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene—Holocene Transition” by Lawrence Guy Straus, Berit Valentin Eriksen (1996) Amazon.com

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

Early Hominins Migrated North Earlier than Thought

The discovery of the 850,000 year-old tools in the river deposit in Happisburgh in the Norfolk area on north-east coast of East Anglia on England's east coast indicated that early humans migrated north earlier than thought and providing valuable information on dispersal of early humans out of Africa. Associated Press reported: “It had been assumed that humans — thought to have emerged from Africa around 1.75 million years ago — kept mostly to relatively warm tropical forests, steppes and Mediterranean areas as they spread across Eurasia. But the discovery of a collection of flint tools some 135 miles northeast of London shows that quite early on, man braved colder climes. "What we found really undermines traditional views about how humans spread and reacted to climate change," said Simon Parfitt, a University College London researcher. "It just shows how little we know about the movement out of Africa." [Source: Associated Press, July 7, 2010 |+|]

“About 75 flint tools have been found at the site near Happisburgh, a seaside hamlet in Norfolk, Parfitt and colleagues report in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature. The researchers dated the artifacts to somewhere between 866,000 to 814,000 years ago or 970,000 to 936,000 years ago. That's at least 100,000 years before the earliest known date for British settlement, in nearby Pakefield. “Exactly what kind of humans made these tools is unknown. "It is impossible to guess who those people were without fossil evidence," said Eric Delson, an anthropologist at Lehman College of the City University of New York, who was not involved in the research. Mammoths and saber-toothed cats roamed the area at that time, and the River Thames flowed into the sea there - about 150 kilometers (90 miles) to the north of where its mouth is today. The climate was a little colder than now, at least during the winter. |+|

“The Natural History Museum's Chris Stringer, another of the paper's authors, said living in such an environment would have been challenging. Thick forests meant a poor supply of edible plants and dispersed prey. In the winter, there would be less daylight for hunting and foraging. Then of course there was the cold. "For humans that have not long emerged from the tropic and the subtropics, that is something," Stringer said. "There's always been the view that that the cold was holding them back." But the find suggests that it didn't. So how did these humans adapt? The researchers said the mix of a tidal river, marshes and coastline at the site might have helped, providing seaweed, tubers, and shellfish when prey was scarce. "We could imagine these people exploiting the slow-flowing banks of the Thames, just as today," Stringer said. |+|

“Co-author Nick Ashton, with the British Museum in London, said that there was still considerable uncertainty about how they adapted. "Have they got effective clothing? Have they got effective shelters? Have they got controlled use of fire?" he said, adding that the find "provides more questions than answers." Delson said that the discovery helped complete Europe's patchy prehistoric record. "We don't know much, but we're increasing our knowledge of the earliest phases of what went on in Europe," he said. "It's one more piece of the puzzle." Stringer, meanwhile, said he hoped more discoveries could be made along the coastline. He noted that he had already seen the chronology of human habitation in Britain pushed back, and then pushed back again. "Now I'm thinking: 'Who knows, can we go back even further?"' |+|”

Hominins Migrated to Cold Northern Regions 800,000 Years Ago Without Fire

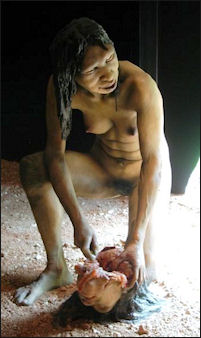

Homo Antecessor female

According to a study published in the March 14, 2011 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Paola Villa, a curator at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History, and Professor Wil Roebroeks of Leiden University in the Netherlands was that early hominins in Europe pushed into the continent’s colder northern latitudes more than 800,000 years ago without the habitual control of fire, said Roebroecks. [Source: University of Colorado Boulder, March 14, 2011 ^^^]

According to the University of Colorado: “Archaeologists have long believed the control of fire was necessary for migrating early humans as a way to reduce their energy loss during winters when temperatures plunged below freezing and resources became more scarce. "This confirms a suspicion we had that went against the opinions of most scientists, who believed it was impossible for humans to penetrate into cold, temperate regions without fire," Villa said. ^^^

“Recent evidence from an 800,000-year-old site in England known as Happisburgh indicates hominins — likely Homo heidelbergenis, the forerunner of Neanderthals — adapted to chilly environments in the region without fire, Roebroeks said. The simplest explanation is that there was no habitual use of fire by early humans prior to roughly 400,000 years ago, indicating that fire was not an essential component of the behavior of the first occupants of Europe's northern latitudes, said Roebroeks. "It is difficult to imagine these people occupying very cold climates without fire, yet this seems to be the case."” ^^^

800,000-year-old foot prints in England near low tide

Hominins Who Made the 850,000-Year-Old Tools in England

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “The flints were probably left by hunter-gatherers of the human species Homo antecessor who eked out a living on the flood plains and marshes that bordered an ancient course of the river Thames that has long since dried up. The flints were then washed downriver and came to rest at the Happisburgh site. The early Britons would have lived alongside sabre-toothed cats and hyenas, primitive horses, red deer and southern mammoths in a climate similar to that of southern Britain today, though winters were typically a few degrees colder. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, July 7, 2010 |=|]

Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, told The Guardian: "These tools from Happisburgh are absolutely mint-fresh. They are exceptionally sharp, which suggests they have not moved far from where they were dropped," The population of Britain at the time most likely numbered in the hundreds or a few thousand at most. "These people probably used the rivers as routes into the landscape. A lot of Britain might have been heavily forested at the time, which would have posed a major problem for humans without strong axes to chop trees down," Stringer added. "They lived out in the open, but we don't know if they had basic clothing, were building primitive shelters, or even had the use of fire." |=|

Until now, the earliest evidence of humans in Britain came from Pakefield, near Lowestoft in Suffolk, where a set of stone tools dated to 700,000 years ago were uncovered in 2005. More sophisticated stone, antler and bone tools were found in the 1990s in Boxgrove, Sussex, which are believed to be half a million years old. "The flint tools from Happisburgh are relatively crude compared with those from Boxgrove, but they are still effective," said Stringer. Early stone tools were fashioned by using a pebble to knock large flakes off a chunk of flint. Later humans used wood and antler hammers to remove much smaller flakes and so make more refined cutting and sawing edges.” |=|

Implication of the 850,000-Year-Old Tools in England

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “The discovery overturns the long-held belief that early humans steered clear of chilly Britain – and the rest of northern Europe – in favour of the more hospitable climate of the Mediterranean. The only human species known to be living in Europe at the time is Homo antecessor, or "pioneer man", whose remains were discovered in the Atapuerca hills of Spain in 2008 and have been dated to between 1.1 million and 1.2 million years old. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, July 7, 2010 |=|]

The early settlers would have walked into Britain across an ancient land bridge that once divided the North Sea from the Atlantic and connected the country to what is now mainland Europe. The first humans probably arrived during a warm interglacial period, but may have retreated as temperatures plummeted in subsequent ice ages. The great migration from Africa saw early humans reach Europe around 1.8 million years ago. Within 500,000 years, humans had become established in the Mediterranean region. Remains have been found at several archaeological sites in Spain, southern France and Italy. |=|

“In an accompanying article in Nature, Andrew Roberts and Rainer Grün at the Australian National University in Canberra, write: "Until the Happisburgh site was found and described, it was thought that these early humans were reluctant to live in the less hospitable climate of northern Europe, which frequently fell into the grip of severe ice ages." |=|

“The latest haul of stone tools was buried in sediments that record a period of history when the polarity of the Earth's magnetic field was reversed. At the time, a compass needle would have pointed south instead of north. The last time this happened was 780,000 years ago, so the tools are at least that old. Analysis of ancient vegetation and pollen in the sediments has revealed that the climate was warm but cooling towards an ice age, which points to two possible times in history, around 840,000 years ago, or 950,000 years ago. Both dates are consistent with the fossilised remains of animals recovered from the same site. "Britain was getting cooler and going into an ice age, but these early humans were hanging in there. They may have been the remnants of an ancient population that either died out or migrated back across the land bridge to a warmer climate," said Stringer.” |=|

800,000-year-old foot prints in England near high tide

800,000-Year-Old Hominin Footprints — Earliest Outside of Africa — Found in England

In 2014, scientists announced that they had discovered the earliest evidence of human footprints outside of Africa, on the Norfolk Coast in the East of England. Direct evidence of the earliest known humans in northern Europe. The footprints are more than 800,000 years old and were found on the shores of Happisburgh. Details of the findings were published in the science journal Plos One. [Source: Pallab Ghosh, BBC News, February 7, 2014 |::|]

Pallab Ghosh of BBC News wrote: “The footprints have been described as "one of the most important discoveries, if not the most important discovery that has been made on [Britain's] shores," by Dr Nick Ashton of the British Museum. "It will rewrite our understanding of the early human occupation of Britain and indeed of Europe," he told BBC News. The markings were first indentified in May last year during a low tide. Rough seas had eroded the sandy beach to reveal a series of elongated hollows. |::|

“Dr Ashton recalled how he and a colleague stumbled across the hollows: "At the time, I wondered 'could these really be the case? If it was the case, these could be the earliest footprints outside Africa and that would be absolutely incredible." Such discoveries are very rare. The Happisburgh footprints are the only ones of this age in Europe and there are only three other sets that are older, all of which are in Africa. "At first, we weren't sure what we were seeing," Dr Ashton told me, "but it was soon clear that the hollows resembled human footprints." |::|

“The hollows were washed away not long after they were identified. The team were, however, able to capture the footprints on video that will be shown at an exhibition at London's Natural History Museum later this month. The video shows the researchers on their hands and knees in cold, driving rain, engaged in a race against time to record the hollows. Dr Ashton recalls how they scooped out rainwater from the footprints so that they could be photographed. "But the rain was filling the hollows as quickly as we could empty them," he told me. |::|

“The team took a 3D scan of the footprints over the following two weeks. A detailed analysis of these images by Dr Isabelle De Groote of Liverpool John Moores University confirmed that the hollows were indeed human footprints, possibly of five people, one adult male and some children. Dr De Groote said she could make out the heel, arch and even toes in some of the prints, the largest of which would have filled a UK shoe size 8 (European size 42; American size 9) . "When I was told about the footprints, I was absolutely stunned," Dr De Groote told BBC News. "They appear to have been made by one adult male who was about 5ft 9in (175cm) tall and the shortest was about 3ft. The other larger footprints could come from young adult males or have been left by females. The glimpse of the past that we are seeing is that we have a family group moving together across the landscape."” |::|

800,000-year-old foot prints in England

Who Made the 800,000-Year-Old Footprints in England?

Pallab Ghosh of BBC News wrote: “It is unclear who these humans were. One suggestion is that they were a species called Homo antecessor, which was known to have lived in southern Europe. It is thought that these people could have made their way to what is now Norfolk across a strip of land that connected the UK to the rest of Europe a million years ago. They would have disappeared around 800,000 years ago because of a much colder climate setting in not long after the footprints were made. [Source: Pallab Ghosh, BBC News, February 7, 2014 |::|]

“It was not until 500,000 years ago that a species called Homo heidelbergensis lived in the UK. It is thought that these people evolved into early Neanderthals some 400,000 years ago. The Neanderthals then lived in Britain intermittently until about 40,000 years ago - a time that coincided with the arrival of our species, Homo sapiens. |::|

“There are no fossils of antecessor in Happisburgh, but the circumstantial evidence of their presence is getting stronger by the day. In 2010, the same research team discovered the stone tools used by such people. And the discovery of the footprints now all but confirms that humans were in Britain nearly a million years ago, according to Prof Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum, who is also involved in the research at Happisburgh. "This discovery gives us even more concrete evidence that there were people there," he told BBC News. "We can now start to look at a group of people and their everyday activities. And if we keep looking, we will find even more evidence of them, hopefully even human fossils. That would be my dream".” |::|

700,000-Year-Old Stone Tools and Mammals in Suffolk

In December 2006, the journal Nature announced the discovery of 700,000-year-old stone tools in Suffolk. The stone tools were flints found by Paul Durbidge and Bob Mutch, two amateur fossil hunters, near a river and beach in Akefeild in eastern England on the foreshore at Pakefield, south of Lowestoft, where winter storms periodically rear up and expose new layers of sediments, sometimes rich in fossils. Thirty-two black flint tools found in river sediments dated to 700,000 years ago are among the the oldest evidence of hominins living in northern Europe. The tools date to a time when England was warm and lions, elephants and saber tooth tigers lived there. Scientists think the humans most likely migrated there during a warm period and did not colonize the area. Before the tools were discovered the earliest evidence of early humans in northern Europe was Boxgrove Man dated to 500,000 years ago.

Mike Pitts wrote in The Guardian: Late in 2001, they hit the jackpot: during an excavation, they found a small flint flake. To the uninitiated, it's just a chip of stone, the sort of thing you might prise out of your sandal. But the two friends saw it for what it was: a diamond amid dross. That little chip of flint had been shaped by the hand of one of the very first Europeans. These flints prove humans to have been there, but it's the animal bones, plant remains, beetles and sediment studies that allow us to picture what it was like. What would it be like, then? Tony Stuart, a leading specialist in ice-age mammals at the University of Durham and UCL, says that at first you would think you were in modern Britain as it might be if it was still wilderness, with broadleaved woodland opening on to marsh around a meandering river rich with pike, tench and rudd — though you might feel a little warm. [Source: Mike Pitts, The Guardian, January 6, 2006

However, he says, "in a short while, familiarity would have given way to astonishment." As a lion roared and hyenas whooped, a mammoth would crash through the undergrowth on its way to the river, upsetting the hippos sunning themselves on the bank. The roster of creatures would make a theme park drawl with envy: an extinct giant beaver, wild boar, three different extinct giant deer, a giant moose, an extinct bison, two species of horse, an extinct rhino, the enormous straight-tusked elephant (larger than any elephant alive today) and the mammoth itself, an ancestor of the (smaller) woolly mammoth of the later ice ages.

There were humans out there, but so few as to be almost unnoticed. The animals' chief concerns were the more vicious carnivores: lion, spotted hyena (Durbidge and Mutch have found not just bones, but droppings too), wolf, bear and the spectacular sabretooth cat. In fact, humans were so rare, it's normal in such work to find a huge range of animals but no fossil hominins.

And what were these early humans like? Well, they predate Neanderthals by hundreds of thousands of years, but still would have been much more like us than our closest living relatives today, the chimpanzees. At Boxgrove in West Sussex a few fossils have been found of Homo heidelbergensis, dating from 500,000 years ago. Pakefield hominins may be their ancestors, and ultimately the Neanderthals' too.

500,000-Year-Old Boxgrove Man

A 500,000-year-old shinbone from a towering six-foot-tall, 200-pound hominin was found near the town of Boxgrove a few miles inland from the English Channel in southern England in 1994. Named Boxgrove Man, the bone was initially heralded by British scientists as belonging to "the earliest European" but later downgraded to belonging to the "first Briton." Boxgrove Man is believed to have arrived between 478,000 and 524,000 years ago, when the British Isles were connected to the European continent by a land bridge.

The shinbone and numerous stone tools found with it were dated by the presence of a vole with molar that disappeared about half million years. The bone was tentatively identified as belonging to “Homo heidelbergensis”. It contain faint chew marks that may have been left by a wild animal that scavenged the corpse. The oldest British remains before that time was a 300,000-year-old skull found in Swanscombe, England.

Europe's Oldest Bone Tools — 500,000 Years Old — Found in Britain

In August 2020, archaeologists announced they say they had identified the earliest known bone tools — including a bone hammer used to make the fine flint bifaces — in Europe. “The bone tools came from a horse that humans butchered for its meat at the site — the famous Boxgrove site in West Sussex, which was excavated in the 1980s and 90s and revealed of thousands of stone tools and fossils dated to around 500,000 years ago, including Boxgrove Man. Some of the tools have scraping marks used to prepare the bone as well as pitting left behind from its use in making flint tools. The findings were detailed in the a book “The Horse Butchery Site.” [Source: Paul Rincon, BBC, August 12, 2020]

The BBC reported: “Flakes of stone in piles around the animal suggest at least eight individuals were making large flint knives for the job. “Researchers also found evidence that other people were present nearby — perhaps younger or older members of a community — shedding light on the social structure of our ancient relatives. They were made by the species Homo heidelbergensis, a possible ancestor for modern humans and Neanderthals. Researchers found a shin bone belonging to one of them — it's the oldest human bone known from Britain.

Project lead, Dr Matthew Pope, from UCL's Institute of Archaeology, said: "This was an exceptionally rare opportunity to examine a site pretty much as it had been left behind by an extinct population, after they had gathered to totally process the carcass of a dead horse on the edge of a coastal marshland. “Incredibly, we've been able to get as close as we can to witnessing the minute-by-minute movement and behaviours of a single apparently tight-knit group of early humans: a community of people, young and old, working together in a co-operative and highly social way."

“The researchers were able to reconstruct the precise type of stone tool that had been made from the chippings left at the site. However, the humans must have taken the tools with them — as they had not been recovered. The researchers believe other members of the group — which could have numbered 30 to 40 people -were nearby. They might have joined the hunting party to butcher the horse carcass. This might explain how it was so completely torn apart: the Boxgrove humans even smashed up the bones to get at the marrow and liquid grease. Dr Pope said that, far from being an activity for a handful of individuals in a hunting party, butchering could have been a highly social event for these ancient humans.

Did Hominins in Germany Wear Bear-Skin Ponchos to Stay Warm 300,000 Years Ago?

Brendan Rascius wrote in the Miami Herald: In order to endure Europe’s frigid winters, Stone Age humans likely wrapped themselves in ponchos fashioned from cave bear skins, according to a study published in the Journal of Human Evolution on December 23, 2022. Researchers came to this conclusion after examining hundreds of prehistoric skeletal remains found in Schöningen, Germany, a small town about 120 miles west of Berlin. “What we could actually show based on cut marks on cave bear bones, is that 300,000 years ago people were skinning bears,” Ivo Verheijen, one of the study’s coauthors, told McClatchy News. “The most plausible reason why people would skin a bear, is to use the pelt for protection against cold weather.” [Source: Brendan Rascius, Miami Herald,, January 10, 2023]

The simplest way to use the pelt would be to “make one cut on the back and wear it like a poncho,” Verheijen said. The findings are significant because clothing does not preserve well over long time periods, meaning there is scant and conflicting evidence of Stone Age garments, according to the study. Specific cut marks found on the bones of cave bears, which went extinct about 25,000 years ago, indicate that the animal was methodically skinned. A series of scrapes on phalanges, an area with little muscle tissue or nutritional value, point toward the skinning and butchering of bear paws, among other body parts.

Specialized tools were likely used to procure the hide, including scrapers and smoothers. Scrapers were employed to remove pieces of meat and tissue, and smoothers were used after to stretch the skin, turning it into a soft, flexible finished product. The skins would’ve had “highly insulating properties,” according to Verheijen, allowing early humans to maintain their body temperatures in the face of cold weather and snow cover.

Creating these bear pelts, an undoubtedly valuable resource, may have been instrumental in allowing humans to survive the inhospitable conditions of Northern Europe, paving the way for their ancestors to settle the continent, according to the researchers. Other prehistoric groups around the world likely wore bear pelts as well, including Native Americans. Their use was illustrated in the movie “The Revenant,” a film set in the uncharted wilderness of the American west, in which Leonardo DiCaprio wears a “similar type of bear poncho,” Verheijen said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Spanish ax from Nature

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024