Home | Category: First Modern Human Life / First Modern Human Art and Culture

EARLY MODERN HUMAN LIFESTYLE AND CULTURE

A lot of our information about early modern human culture comes from Europe, not necessarily because early man there was more culturally astute but because the region has been more intensively studied. The Aurignacian (42,000 to 28,000 years ago), Gravettian (28,000 to 22,000 years ago), Solutrean (22,000 to 18,000 years ago) and Magdalenian (18,000 to 10,000 years ago) cultures are all named French sites. Each site has tools, weapons and adornment associated with it.

Around 40,000 years ago, when modern humans began arriving in Europe in large numbers, glaciers covered most of Britain and Europe as far south as Germany. Animals included wooly rhinoceros, musk oxen, chamois, ibex, reindeer, saiga antelope, cave bears, horses, steppe bison, giant elk, wooly mammoths, red deer, lions, woodland bison, wild ass, salmon, fallow deer, ringed seals, and aurochs (large, long-horned wild oxen). By 15,000 years ago the Ice Age was largely over, large of herds of animals roamed steppe grasslands and forests, salmon was abundant in the rivers and the Neanderthals were long gone. By 12,000 years ago wetter weather dominated, enough glacial ice had melted to swamp coastal areas.

The first modern humans found shelter in Potok Cave, Slovenia , which encompasses nearly 7,010 meters (23,000 feet) of limestone tunnels, and used it as a ritual site or hunting station some 36,000 years ago. [Source: National Geographic]

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Paleolithic Revolution (The First Humans and Early Civilizations)” by Paula Johanson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Paleolithic Technologies (Routledge Studies in Archaeology)”

by Steven L. Kuhn Amazon.com;

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature” by Ludovic Slimak Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Human Culture”by Richard G. Klein (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Prehistory of the Mind: A Search for the Origins of Art, Religion and Science

by Prof Steven Mithen (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins” by Richard G. Klein Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow Amazon.com;

“Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind” by Colin Renfrew (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Culture: Based on an Interdisciplinary Symposium ‘The Nature of Culture’, Tübingen, Germany by Miriam N. Haidle (2016) Amazon.com;

“he Archaeology of Childhood: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on an Archaeological Enigma” by Güner Coşkunsu (2016) Amazon.com;

“Culture History and Convergent Evolution: Can We Detect Populations in Prehistory?

by Huw S. Groucutt (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sounds of Laughter, Shades of Life: Pleistocene to modern hominin occupations of the Bau de l'Aubesier rock shelter, Vaucluse, France” by Lucy Wilson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought”

by Pascal Boyer (2002) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age”

by Robert N. Bellah (2017) Amazon.com;

Population Trends Beginning About 100,000 Years Ago

100,000 Years Ago: Michael Balter wrote in Discover: Artistic Behavior Appears: Most researchers date the origins of Homo sapiens to between 200,000 and 160,000 years ago in Africa. Yet for their first 100,000 years, modern humans behaved like their more archaic ancestors, producing simple stone tools and showing few signs of the artistic sparks that would come to characterize human behavior. Scientists have long argued about this gap between when humans started looking modern and when they began acting modern. University College London archaeologist Stephen Shennan has proposed that cultural innovations were likely due to increased contact among humans as they began living in ever-larger groups. Shennan adapted Henrich’s Tasmanian model to much earlier human populations. When he plugged in estimates of prehistoric population sizes and densities, he found that the ideal demographic conditions for advancement began in Africa 100,000 years ago—just when signs of modern behavior first emerge.” [Source: Michael Balter, Discover October 18, 2012]

65,000 “Years Ago: Stone Tools Spread: Population size could explain why the same stone tool innovations show up at the same time across wide geographic regions. Lyn Wadley, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, has worked at the Middle Stone Age site of Sibudu in South Africa, where she found evidence of two sophisticated tool traditions dating to 71,000–72,000 years ago and 60,000–65,000 years ago. Similar tools pop up all across southern Africa at around the same time. Wadley says early humans did not have to migrate long distances for this kind of cultural transmission to take place. Instead, increasing population densities in Africa may have made it easier for people to keep in contact with neighboring groups, possibly to exchange mating partners. Such meetings would have exchanged ideas as well as genes, thus setting off a chain reaction of innovation across the continent.”

45,000 Years Ago: “Homo Sapiens Takes Europe: A bigger population may have helped H. sapiens eliminate its chief rival for domination of the planet: the Neanderthals. When modern humans began moving into Europe about 45,000 years ago, the Neanderthals had already been there for at least 100,000 years. But by 35,000 years ago, the Neanderthals were extinct. Last year Cambridge University archaeologist Paul Mellars analyzed modern human and Neanderthal sites in southern France. Looking at indicators of population size and density (such as the number of stone tools, animal remains, and total number of sites), he concluded that modern humans—who may have had a population of only a few thousand when they first arrived on the continent—came to outnumber the Neanderthals by a factor of ten to one. Numerical supremacy must have been an overwhelming factor that allowed modern humans to outcompete their larger rivals.”

45,000 Years Ago: “Homo Sapiens Takes Europe: A bigger population may have helped H. sapiens eliminate its chief rival for domination of the planet: the Neanderthals. When modern humans began moving into Europe about 45,000 years ago, the Neanderthals had already been there for at least 100,000 years. But by 35,000 years ago, the Neanderthals were extinct. Last year Cambridge University archaeologist Paul Mellars analyzed modern human and Neanderthal sites in southern France. Looking at indicators of population size and density (such as the number of stone tools, animal remains, and total number of sites), he concluded that modern humans—who may have had a population of only a few thousand when they first arrived on the continent—came to outnumber the Neanderthals by a factor of ten to one. Numerical supremacy must have been an overwhelming factor that allowed modern humans to outcompete their larger rivals.”

25,000 Years Ago: “Ice Age Exerts A Toll: By 35,000 years ago, H. sapiens appears to have had the planet to itself, with the possible exception of an isolated population of H. floresiensis—the “hobbit” people of Southeast Asia—and another newly discovered hominid species in China. But according to work led by University of Auckland anthropologist Quentin Atkinson, human population growth, at least outside of Africa, began to slow down around then, possibly due to the climate changes associated with a new ice age. In Europe, total human numbers may actually have declined as glaciers began to cover much of the northern part of the continent and humans retreated farther south. But population levels never dropped enough for humans to start losing their technological and symbolic innovations. When the Ice Age ended, about 15,000 years ago, population began to climb again, setting the stage for a major turning point in human evolution.”

11,000 Years Ago: “Farming Sparks a Boom: Farming villages first appeared in the Near East during the Neolithic period, about 11,000 years ago, and soon afterwards in many other parts of the world. They marked the beginning of a transition from the nomadic hunting and gathering lifestyle to a settled existence based on cultivating plants and herding animals. That transition helped catapult the world’s population from perhaps 6 million on the eve of the invention of agriculture to 7 billion today. Archaeologist Jean-Pierre Bocquet-Appel has surveyed cemeteries across Europe associated with early settlements and found that with the advent of farming came an increase in the skeletons of juveniles. Bocquet-Appel argues this is a sign of increased female fertility caused by a decrease in the interval between births, which probably resulted from both the new sedentary life and higher-calorie diets. This period marks the most fundamental demographic shift in human history.”

First Great Human Population Explosion: 60,000-80,000 Years Ago

Contrary to what had been previously thought the first human population explosion occurred with hunter-gatherers 60,000-80,000 years ago, not with the first farmers around 10,000-12,000, a genetic study suggested. Popular Archaeology reported: “The prevailing theory is that, as humans transitioned to domesticating plants and animals around 10,000 years ago, they developed a more sedentary lifestyle, leading to settlements, the development of new agricultural techniques, and relatively rapid population expansion from 4-6 million people to 60-70 million by 4,000 B.C. [Source: Popular Archaeology, September 24, 2013 \=/]

Contrary to what had been previously thought the first human population explosion occurred with hunter-gatherers 60,000-80,000 years ago, not with the first farmers around 10,000-12,000, a genetic study suggested. Popular Archaeology reported: “The prevailing theory is that, as humans transitioned to domesticating plants and animals around 10,000 years ago, they developed a more sedentary lifestyle, leading to settlements, the development of new agricultural techniques, and relatively rapid population expansion from 4-6 million people to 60-70 million by 4,000 B.C. [Source: Popular Archaeology, September 24, 2013 \=/]

“But hold on, say the authors of a recently completed genetic study. Carla Aimé and her colleagues at Laboratoire Eco-Anthropologie et Ethnobiologie, University of Paris, conducted a study using 20 different genomic regions and mitochondrial DNA of individuals from 66 African and Eurasian populations, and compared the genetic results with archaeological findings. They concluded that the first big expansion of human populations may be much older than the one associated with the emergence of farming and herding, and that it could date as far back as Paleolithic times, or 60,000-80,000 years ago. The humans who lived during this time period were hunter-gatherers. The authors hypothesize that the early population expansion could be associated with the emergence of new, more sophisticated hunting technologies, as evidenced in some archaeolocal findings. Moreover, they state, environmental changes could possibly have played a role. \=/

“The researchers also showed that populations who adopted the farming lifestyle during the Neolithic Period (10,200 – 3,000 B.C.) had experienced the most robust Paleolithic expansions prior to the transition to agriculture. “Human populations could have started to increase in Paleolithic times, and strong Paleolithic expansions in some populations may have ultimately favored their shift toward agriculture during the Neolithic,” said Aimé. The details of the study have been published in the scientific journal, Molecular Biology and Evolution, by Oxford University Press.” \=/

Early Modern Man Society

Early humans grouped together in family bands and subsisted mainly by gathering plants, scavenging, hunting and fishing. In Europe, early modern men were highly skilled nomadic hunters. Following seasonal migrations, they used the atlatl, or spear thrower, which greatly enhanced their prowess, and perhaps bow and arrow. Reindeer was favorite prey. They lived in caves and rock shelters, formed groups with perhaps as many as 50 to 75 members, and cooked in stone-lined pits. [Source: Kenneth Weaver, National Geographic, November 1985 [┹] .

The assumption that early homo sapiens struggled to survive and lived "short, nasty and brutish" lives is probably a little misleading. Studies of apes have shown that chimpanzees and gorillas spend as much time relaxing, playing and grooming as they do foraging for food. Anthropology studies have shown that the Machiguenga, simple horticulturists from the Peruvian Amazon, and bushmen — hunters and gatherers who live in the harsh Kalahari desert — spend less than three hours per person obtaining food.

Hominin remains shows that some members of a community were better off others. There are 20,000-year-old burial sites with graves with large numbers of ivory objects, beads and teeth from animals such as lions and bears and other grave sites with graves with virtually nothing indicated there may have social stratification based on wealth and status.

One thing that makes modern humans what they are is their prolonged childhood. Studies of Neanderthal teeth indicate they matured faster than humans with growth lines in the tooth of an eight-year-year old Neanderthal being equivalent to that of a 10- to 12-year-old human.

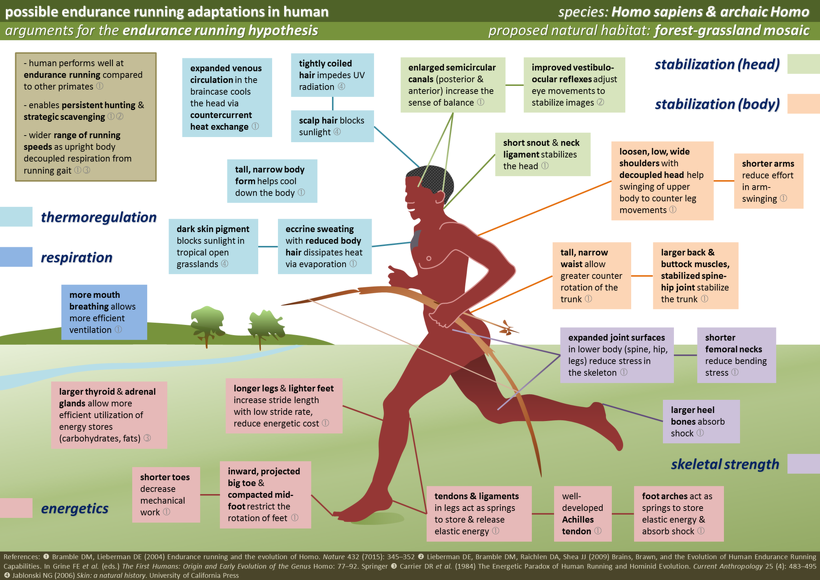

Man, the Long-Distance Runner

One characteristic of modern humans that may have played an important part in their ability to endure and prosper during prehistoric times was his prowess at long distance running. While modern humana are terrible sprinters (they can be outrun by lions cheetahs, dogs, horses, rabbits and even squirrels) their ability as long distance runners — at least that of seasoned marathon runners — is unparalleled. Over distances of several miles man can outlast many animals, even gazelles and horses. Some bushmen in Africa and Aboriginals in Australia still hunt by injuring prey, such as a gazelle or kangaroos, and following them for hours even days until the animals collapse from exhaustion.

One of the primarily mechanism that allows man to run such long distanced and have such extraordinary endurance is the human cooling system. Many animals rely on panting as a cooling mechanism but that interferes with respiration. This not a problem for sprintingg but it is for distance running,. Humans in the words of Harvard evolutionary biologies Daniel Lieberman are “specialized sweaters” — able to dispense heat using its dense network of sweat glands.

In his book “Manthropology” , Peter McAllister argues that 20,000-year-old footprint from the Australian outback shows that prehistoric Aborigines could have outrun Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt.

Early Modern Humans as Hunters and Gatherers

To gain insight into how early modern humans behaved and were organized, anthropologists have studied early hunter gather tribes such as bushman. In traditional hunter-gatherer societies the women and young usually gather roots, fruits, berries and plant food while men hunt for meat. Most of the calories come from the women's work. Men often come home empty-handed, which means that it falls to the women to provide much of the food. This kind of arrangement seems likely with early modern humans.

Early modern humans probably traveled in bands with 10 to 30 individuals, based on way modern stone age tribes behave. By diversifying tasks along gender and age lines and getting food from a variety of sources such groups were relatively flexible and adaptable. If one food source, for example, gave out they could easily find another. By contrast Neanderthal were specialized big game hunters and when big game gave out — possibly — so too did they.

Mary Stone of the University of Arizona told National Geographic, “By diversifying duties and having personnel who [did different tasks] you have a formula for spreading risk, and this is ultimately good news for pregnant women and for kids. So if one things falls through there’s something else.” More specialized individuals seem to have led to the organization of larger groups (her is evidence is the formation of larger groups as modern humans evolved) and the increased social activity led to more sophisticated language and brain development which in turn produced, the reasoning goes, a “culture of innovation” and longer life spans.

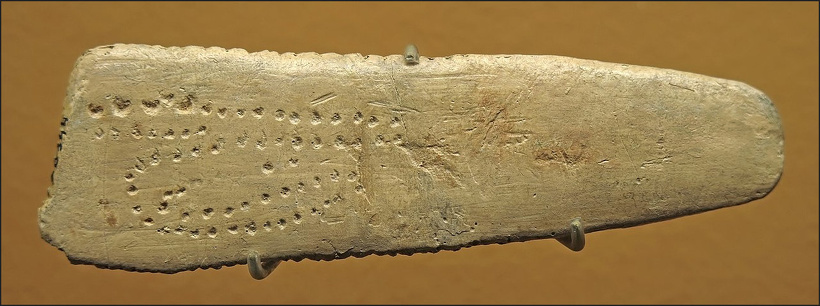

Fishing developed over 30,000 years ago. It took some skill to make fish hooks. Before that took place early man may have used nets or driven fish into areas where they could be speared. There is no real archaeological evidence to back this up however. Large accumulations of fish bones and shells found at early man sites indicates early man ate fish and shellfish. Collecting clams and other mollusks isn’t very difficult and was probably one of the easier food sources that early man could exploit. Two Paleolithic harpoons, said to be at least 60,000 years old and decorated with geometric figures, were discovered at Veyrier near Geneva.

Modern Humans Who Lived in French Rock Shelters 40,000 Years Ago

Abri Blanchard and Castanet are rock shelters that sit along a cliff face in the Castel Merle Valley, just beyond the small commune of Sergeac, in France’s Dordogne, which is famous for early modern human sites. Almost 40,000 years ago, Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: Abri Blanchard and Abri Castanet played host to families of hunter-gatherers who spent the winter huddled around fires, engaging in the exchange of objects and materials with their neighbors. The wealth of evidence uncovered points to the development of a highly structured domestic space with distinct areas for various activities. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

“The hunter-gatherers who assembled at Abri Castanet and Abri Blanchard would have primarily eaten reindeer, the bones of which make up more than 90 percent of the animal remains found. White speculates they would have been hunted one at a time. The rock shelters were likely one of many sites occupied during what White calls the typical hunter-gatherer pattern of aggregation and dispersal. “We’re a little perplexed about why all these symbolic activities are here,” White explains. “It’s a rather inhospitable place to live.” He notes that Castel Merle would have had cold air currents, causing it to be a few degrees cooler than the rest of the Vézère River valley.

“The preponderance of reindeer near the Vézère might have lured early Aurignacian people during the winter because the animals’ hides would have made ideal coverings and clothing. Summer occupation sites may have been as far flung as Brassempouy, 150 miles southwest, near France’s Atlantic coast. That site, famous for its Venus, the head of an ivory figurine dating back 25,000 years, includes some of the same ornamentation found at the Castel Merle sites. Faunal remains at Brassempouy are of reindeer, as well as horses and bovids, such as sheep, goats, and wild oxen. “We don’t have these people’s seasonal trajectory figured out,” says White, noting that the evidence of bead production seen at Abri Blanchard and Abri Castanet far outstrips that seen at other contemporary sites, like Brassempouy. Much of the material used to make beads and other ornamentation comes from far away. Soapstone from the central Pyrenees Mountains and seashells from both the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea have been found at Castel Merle. There’s no evidence that mammoths roamed southwestern France, so ivory could have come from southern Germany.

See Separate Article: HOMO ERECTUS LIFE, STRUCTURES, LANGUAGE, ART AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Modern Humans Activities at Abri Castanet 40,000 Years Ago

Tools found at Abri Castanet include keeled scrapers made of flint and spear points made of reindeer bones and antlers. Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: “There’s no evidence, however, of the production of blades, though Peyrony’s excavation notes include the discovery of many flint cores from which blades had likely been struck. White explains that this is further evidence of the organized distribution of disparate activities taking place throughout the site. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

White excavated the 300-square-foot “Castanet South,” as he calls it, until 2010, recovering 150,000 artifacts — from limestone blocks to burnt antler bones to tiny ornamental beads. His team is meticulous, excavating in two-and-a-half-square-foot blocks and retaining every particle down to 0.05 inches in size. There were four fire features uncovered in Abri Castanet’s southern sector. Using magnetic susceptibility, which identifies iron-rich patches of soil that are indicative of burning, the team was able to identify a central fire pit, roughly one foot in diameter and one foot deep, dug directly into the bedrock. It appeared to have been renovated continuously for multiple uses.

Nearly 40,000 years ago, Abri Castanet was a site where some of Europe's first modern humans made hundreds of basket-shaped beads from ivory.White notes there are distinct areas where certain types of artifacts are found, and specific activities were carried out around the central fire pit. To the northwest, toward the front of Castanet South, is an eight-square-foot section where 80 percent of the debris from the manufacturing of ornamental ivory beads was found. “This is prime bead-making area,” he says.“I first came here because these sites had yielded so many beads.”

“Claire Heckel, a Ph.D. candidate in archaeology at New York University, describes the beads, hundreds of which have been recovered, as “basket-shaped,” rounded at the base with a little handle. They measure a quarter of an inch on average and were likely sewn onto garments with horse hair or another plant or animal fiber. “What was probably driving the advent of this behavior were distant social networks coming together that required signaling your identity to people who may not know your status,” Heckel explains.

“One of the fire features is full of burnt antler bone that White believes was probably shaped into points with split bases for hand-thrown spear tips — the hunting weapon that predated the atlatl. Elsewhere, there are waste flint flakes that suggest it may have been a spot where stone tools were sharpened. Twenty percent of the tools at the site are made of flint from Bergerac, a commune roughly 40 miles west of Castel Merle, indicating that Aurignacians likely came here by way of Bergerac. Romain Mensan says the tool kit found at Castanet South includes end scrapers, keeled scrapers, and large blades with fish-scale patterns that could be up to nearly a foot in length.

an idiophone from Abri Castanet, played by running a stick along the well-worn notches on the top and bottom

Family Life 14,000 Years Ago Depicted in Footprints

Lydia Pyne wrote in Archaeology magazine: A rare view of family life some 14,000 years ago has been made possible by recent studies and 3-D modeling of the traces left by a group of five people who walked, crawled, and explored their way through Grotta della Basura in the Liguria region of northern Italy. [Source: Lydia Pyne, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

The cave was originally explored in the 1950s, but an international team of researchers recently modeled 180 footprints, as well as finger- and knee prints. They retraced the movements of the group — two adults, one preadolescent, one six-year-old, and a three-year-old — and reconstructed how they explored the cave.

They can be “seen” hugging the cave’s edge, crouching down and walkcrawling where the ceiling drops low, and falling into a single-file line, with the three-year-old at the back, in one of the cave’s narrow chambers. In the chamber farthest from the entrance, called the Room of Mysteries, smears of clay on a stalagmite — a sort of Paleolithic finger painting — were made by the two youngest children.

Ice Age Children Toys

Researchers, led by Dr Michelle Langley, an associate professor of archaeology at Griffith University in Queensland, published in an article in 2017 about “archaeologically invisible” Ice Age children and their toys. Archaeologists long thought it was impossible to find toys from so long ago and looking for children for evidence from this period is a relatively new archaeological endevour. Langley said by looking at what toys children in present-day hunter-gatherer communities played with they could identify likely playthings used by children who lived tens of thousands of years ago.“These playthings commonly include dolls or figurines, small spears or bows-and-arrows, small versions of the tools commonly used by their parents, and mud figures,” she said. “It was also found that often the parents or other family members will spend many hours making beautiful and often expensive toys for their children.” [Source: Griffith University, November 29, 2017]

In her paper in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Dr Langley writes that previously researchers had been able to find evidence for children learning how to make stone tools, and perhaps learning how to be artists. Her paper, studying the people who created the great cave art of France and Spain is, however, looking for more. “We know that playing with toys is a cultural universal, so we can expect that toys included by children in their games thousands of years ago should have made their way into the archaeological record, as everything used by people does,” Dr Langley said. “Knowing that they must be present, however, does not make them any easier to find.Archaeologists should be finding small dolls/animal figurines, small tools, and weapons in their sites – these may have been toys lost by children in the past.

“For the Palaeolithic period such dolls/figures have been found and are widely celebrated for their beauty and appeal to our modern Western aesthetics. Because of these factors, researchers have previously thought they were special art or ritual items for the use by adults – rather than a child’s toy. They were too beautiful, and took too much skill and effort to create to be simply given to children to play with.” Dr Langley said the new research suggested that at least some of these figurines may have instead been children’s toys. “Reinterpreting some of these figurines and other small items effectively makes the many children who grew up in the Ice Age visible again,” she said.

Early Man Hygiene, Diseases and Health Problems

There is evidence that men shaved as far back as 20,000 years ago. There are cave drawings with beardless men, Sharpened flints and shells have been found in graves that may have been used as razors.

Diseases like malaria were probably not as much of problem during Paleolithic times as they are today because hunter-gatherers at that time seemed to have preferred dry, open habitats to wetlands and rain forests. Also people lived in scattered groups which makes it much more difficult to pass on infectious diseases. Infant mortality rates were very high. Even so, some scientists have hypothesized that since infectious diseases were less of threat than in ancient urban areas if early modern humans managed to emerge from childhood unscathed they could look forward to a longer lifespan than Greeks and Romans.

The skeleton of one individual found at Cro-Magnon was judged to be male about 50 years old at the time of his death. Researchers observed damage to his bone structure, indicating he likely had a debilitating fungal infection. Some of the other skeletons had fused spines, indicating that they had endured "traumatic injury." One adult female seemed to have survived a period of time with a skull fracture. The injuries also show that early modern humans probably cared for one another, tending to each other's injuries perhaps so the entire group could benefit. [Source: Sara Novak, Discover Magazine, April 9, 2024]

Earliest Known Amputation — 31,000 Years Ago in Borneo

Evidence of the earliest known amputation comes from Liang Tebo Cave in East Kalimantan, Borneo Indonesia. Describing in a study published in September 2022 in Nature, the successful surgery was performed on a teenager 31,000 years ago, when the person’s lower left leg was skillfully removed. It is believed that the patient survived the procedure and lived for another six to nine years before succumbing to an unknown cause of death. The individual also displayed signs of a healed neck fracture and clavicle trauma, both of which may have occurred during the same event in which the leg was injured. The researchers concluded that the amputation was unlikely caused by an animal attack or other accident, as these typically cause crushing fractures. It is also unlikely the amputation had been carried out as a form of punishment, because the individual seems to have received careful treatment after surgery and in burial, according to the study. [Source: Archaeology magazine, January 2023]

Archaeologists located the skeleton in 2020 after returning to the site where some of the earliest rock art was previously found, searching for archaeological deposits that may overlap with this early rock art, Tim Maloney, an archaeologist at Griffith University in Australia and lead author of the study, said. The researchers "slowly and meticulously" studied the skeleton, removing the sediments surrounding the burial as well as laser scanning and photographing, Maloney said. Once it was excavated, it was "quite clear" that the skeleton's left foot was "entirely absent" and that an amputation occurred on the lower or distal third of their left leg, Maloney said. A paleopathologist confirmed the skeleton presented a strong case for matching clinical instances of deliberate amputation, Maloney said. Previously, the oldest known complex operation happened to a Neolithic farmer from France about 7,000 years ago, according to the study. The farmer's left forearm had been surgically removed and then partially healed.[Source: ABC News, September 7, 2022]

Tborno he finding was significant because amputations require a comprehensive knowledge of human anatomy and surgical hygiene, as well as significant technical skill, the researchers said. In addition, most people who underwent amputation surgery died from blood loss and shock or subsequent infection before modern clinical developments such as antiseptics, according to the study. In addition, the person who performed the amputation must have possessed detailed knowledge of limb structure, muscles and blood vessels to prevent fatal blood loss and infection, according to the study.

The findings suggest some early modern human foraging groups in Asia developed advanced medical knowledge and skills in the tropical rainforest environment in the Late Pleistocene period, which was connected to mainland Southeast Asia at the time that the individual who was found lived, Maloney said. The skills may have been required as a result of rapid rates of wound infection in the tropics stimulated the development of novel pharmaceuticals such as antiseptics, which were harnessed from the medicinal properties of the rich plant biodiversity in Borneo. "There's a very strong case we make for understanding of the needs for antiseptic and antimicrobial management to enable the patient this individual to survive," Maloney said.

Genetic Impact of Our Human Ancestors on Us Today

Many diseases and health problems that affect humans today — diabetes, hypertension and obesity — are partly the consequence of natural selection that took place long ago in a world that was far different than the one we live in today. Remnants of extinct retoviruses that infected our ancestors millions of years ago make up about 8 percent of our DNA. Scientists at the Aaraon Diamond AIDS Research Center in New York have recently put together pieces of one prehistoric virus — the 45-million-year-old HERV-K — creating an active, replicating retrovirus. They did this by comparing the genomes of 10 versions of the virus, identifying mutation in each, and deducing what a healthy virus must have looked like. They then assembled that version, tested it, and found it was able to replicate and infect cells in the lab.

Over the past 10,000 year several mutations have been “naturally selected” to protect humans from malaria. Behind the changes is the Darwinian concept that any mutation that protects a victim from an early death will allow them to reproduce and spread the mutation. Africans have developed a number of genetic mutations that protect them against malaria that became widespread even though they also caused sickle cell anemia , thalassemia and G6PD deficiency. Mutations that fight the disease have also been found in Thailand and New Guinea, where malaria is also prevalent.

A coronavirus epidemic 25,000 years ago could help treat modern coronavirus study finds. The Telegraph reported: Scientists have identified a set of 42 genes which were altered after coming into contact with coronavirus some 900 generations ago. The adaptations were caused by a "multigenerational coronavirus epidemic" among East Asian populations, the researchers from the USA and Australia concluded. “This likely triggered an "arms race", similar to today's worldwide rush to find a vaccine against Covid-19, the study suggests. The scientists studied 26 populations from five regions in East Asia using data from the 1000 Genomes Project — the largest public catalogue of human genomic data. [Source: Phoebe Southworth, The Telegraph, November 21, 2020]

“These findings could help scientists currently working on developing treatments for Covid-19, as drugs could be tailored to target the 42 genes identified as being impacted by the virus in the past, the researchers say. They also believe future pandemics could be prevented altogether. “Modern human genomes contain evolutionary information tracing back tens of thousands of years, which may help identify the viruses that have impacted our ancestors — pointing to which viruses have future pandemic potential," the study states. “By revealing the identity of our ancient pathogenic foes, evolutionary genomic methods may ultimately improve our ability to predict — and thus prevent — the epidemics of the future."

Five Caveman Desires That Remain with Us Today

Addressing was the consequences of living in the modern world with a Stone Age body, Harvard evolutionary biologist Jason Lieberman said during a public lecture in 2013 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. "Like it or not, we evolved to be sweaty, fat bipeds that are furless and big brained. We evolved to crave sugar, starch and fat. We evolved to be physically active, but we also evolved to be lazy." [Source: Laura Poppick, Live Science, November 12, 2013]

Laura Poppick wrote in Live Science: “During the talk, Lieberman described some of the ways that instincts humans inherited from the Stone Age — also known as the Paleolithic Period, stretching from between 2.6 million to about 10,000 years ago — now conflict with modern life and contribute to increasingly common lifestyle-induced diseases such as Type 2 diabetes and heart disease. Humans crave high-energy foods, like fats and carbohydrates, because such food was hard to come by in the Stone Age, but can now be consumed in great abundance to the detriment of the body. Meanwhile, humans typically opt out of energy-intensive habits, such as walking to destinations, because people also inherited brains hardwired to want to save energy. Here are five day-to-day decisions modern humans face that are made complicated by their Stone Age bodies.

“1) Stairs or escalator: The sight of a flight of stairs next to an escalator probably strikes up a similar internal dialogue within most people. "Hmm, stairs … yeah, I'll take the escalator. Although, I could probably use the exerci … no, I'll take the escalator." One study that measured the percentage of people in the United States who chose stairs over escalators when both were available side by side found that only 3 percent chose the stairs, Lieberman said. But a habit that modern people might view as lazy would have been considered smart by humanity's ancestors: Hunting and gathering was energy-intensive, and short breaks of inactivity offered the rare chance to save hard-earned calories. "If there were escalators in the Kalahari Desert, they would be using them too," Lieberman said during his talk, referring to human ancestors. "And it makes sense that they would."

“2) Walk all day or sit all day: Humans evolved to be a walking species. Whereas chimps walk an average of about 2 to 3 kilometers per day (1.2 to 1.9 miles) — spending most of their time foraging and chomping on vegetation — hunter-gatherers are thought to have walked 9 or more kilometers (5.6 miles) every day, Lieberman said. "We evolved to walk, run, climb, dig and throw," Lieberman said. "That's how hunter-gatherers got their dinner every day." Walking keeps humans healthy by stimulating blood flow and flushing oxygen through the body. But today, modern civilization thrives largely on long-term sitting, to the detriment of physical and mental health. People do have the option to exercise, and take time out of the day to work those muscles that were built to be used. But this conscious decision to burn excess energy is not a decision the human body evolved to need to make.

“4) Read or don't read: Nobody would argue that reading is bad for human health. But Lieberman pointed out that myopia — also known as nearsightedness, when far-away objects look blurry — has increased substantially with the advent of writing and reading. This is because the eye muscles, which are not made for prolonged up-close vision, must strain to look at things close to the face, and eventually they stretch and elongate to the point that they no longer function properly. Increasingly longer hours spent inside office buildings and homes, rather than visually stimulating landscapes like forests and other natural spaces, can also lead to sight problems, Lieberman said. But humans take this risk, and manage to get by fine with glasses.

“5) Sugar or veggies: Some estimates suggest the Paleolithic diet consisted of 4 to 8 lbs of sugar per year. Today, the average American consumes more than 100 lbs (45 kilograms) of sugar per year, Lieberman said. This drastic increase had been partially implicated in the rise of heart disease and diabetes as leading causes of death in the country over the past several decades. But cavemen weren't watching their calories; they just didn't have access to the huge quantities of sugar available today. Modern technology allows humans to extract sugar from a wide range of sources — including sugar cane, maple trees, beehives and corn stalks — and ship that sugar around the world in huge quantities and at unprecedented speeds. If given the chance to gorge on candy bars, Paleolithic children probably would have wanted to just as much as modern children do, Lieberman said. But they just didn't have that option. "That kid had no option but to eat healthy food and to exercise, because that is what she did every day," Lieberman said. "Now we have to teach our children to make choices for which we are not really prepared for from an evolutionary perspective."

Did Prehistoric Painters Purposely Deprive Themselves of Oxygen to Get High

Prehistoric cave dwellers in Europe starved themselves of oxygen on purpose to hallucinate while creating their wall paintings, according to a study by Tel Aviv University researchers published in the scientific journal "Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture" in April 2021.Researchers have long wondered why so many of the world's oldest paintings were located deep inside cave systems, where it is pitch-black dark, instead of closer to cave entrances. The study argues that the location was deliberate because it induced oxygen deprivation and caused cavemen to experience a state called hypoxia.

Business Insider reported: “Hypoxia can bring about symptoms including shortness of breath, headaches, confusion, and rapid heartbeat, which can lead to feelings of euphoria, near-death experiences, and out-of-body sensations. The team of researchers believes it would have been "very similar to when you are taking drugs", the Times reported. [Source: Sophia Ankel, Business Insider, April 12, 2021]

"It appears that Upper Paleolithic people barely used the interior of deep caves for daily, domestic activities. Such activities were mostly performed at open-air sites, rock shelters, or cave entrances," the study says, "While depictions were not created solely in the deep and dark parts of the caves, images at such locations are a very impressive aspect of cave depictions and are thus the focus of this study."

“According to Ran Barkai, the co-author of the study, the cavemen used fire to light up the caves, which would simultaneously also reduce oxygen levels. Painting in these conditions was done deliberately and as a means of connecting to the cosmos, the researcher says. "It was used to get connected with things," Barkai told CNN, adding that cave painters often thought of the rock face as a portal connecting their world with the underworld, which was associated with prosperity and growth. The researcher also suggested that cave paintings could have been used as part of a kind of initiation rite.

The study focused on decorated caves in Europe, mostly in Spain and France. The cave paintings, which date from around 40,000 to 14,000 years ago, depict animals such as mammoths, bison, and ibex. "It was not the decoration that rendered the caves significant but the opposite: The significance of the chosen caves was the reason for their decoration," the study reads, according to CNN.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated May 2024