Home | Category: The Gospels and Early Christian Texts

NAG HAMMADI MANUSCRIPTS

Gnostic Dag Hammadi

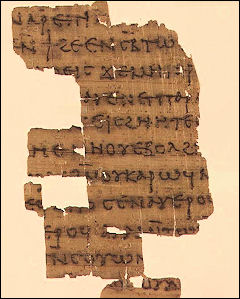

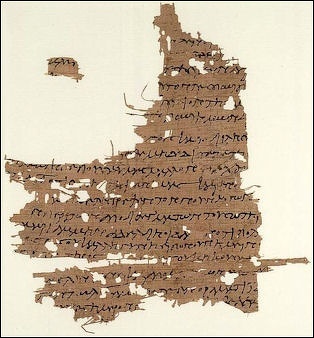

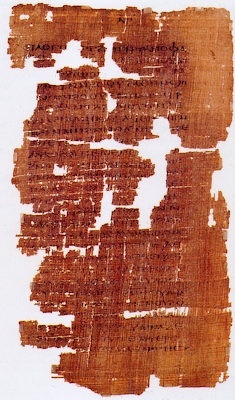

Dialogue of the Savior Many early Christian texts that remain with us today are Nag Hammadi manuscripts, a trove of ancient papyri books found in the village of Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt in 1945. Written in Coptic, the manuscripts consisted of 13 codexes (ancient books with pages) with 52 texts that were stored in a heavy waist-high clay jar and may have been stored there by monks from the nearby monasteries of St. Pachpmius.

Some regard the Nag Hammadi manuscripts to be as important as the Dead Sea scrolls. The 52 texts found there include previously unknown Gnostic gospels, epistles, apocalypses and other religious writings held sacred to early Christian groups . They had titles like “The Secret Book of James” , “The Apocalypse of Peter” , “The Gospel of Philip” and The “Gospel of Thomas” . Most were dated to the A.D. 4th century but are likely translations of Greek originals that dated back to as early as the A.D.1st century.

Initially the Nag Hammadi texts were only of interest to religious scholars, many of whom dismissed them as offering few new insights into the historical Jesus. But in recent years they have been reexamined and are now regarded as important materials to understanding the development of Christianity.

The Nag Hammadi manuscripts were found by an Arab peasant named Muhammed Ali al-Sammam while collecting dung as fertilizer for his fields. He took the texts home and tossed them in courtyard used by his animals. Before they made their way to antiques dealers and scholars some pages were used to light stoves and others were bartered for cigarettes.

See Separate Articles: GNOSTIC BELIEFS AND TEXTS factsanddetails.com and APOCRYPHA FROM THE NEW TESTAMENT europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Bible: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts” by Marvin W. Meyer, Elaine H. Pagels, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Gnostic Gospels” by Elaine Pagels, Lorna Raver, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Gnostics” by Jacques Lacarriere Amazon.com ;

“Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas” by Elaine Pagels Amazon.com ;

"Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It Into the New Testament" by Bart D. Ehrman Amazon.com ;

“The New Testament Apocrypha” by M R James Amazon.com ;

“The Apocryphal Gospels” by Simon Gathercole (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Gnostic Discoveries: The Impact of the Nag Hammandi Library” by Marvin W. Meyer Amazon.com ;

“The Complete 54-Book Apocrypha: 2022 Edition With the Deuterocanon, 1-3 Enoch, Giants, Jasher, Jubilees, Pseudepigrapha, & the Apostolic Fathers Amazon.com ;

“The Ultimate 84-Book Apocrypha - The Largest and Most Complete Collection of Lost Biblical Texts Amazon.com

Nag Hammadi Library

According to Time magazine: “The Nag Hammadi texts were packed away 16 centuries ago, perhaps to protect them from book-burning Christian opponents... Most of them ended up in Cairo's Coptic Museum. Yet because of scholarly rivalries and unsettled political conditions in Egypt, no comprehensive study of the entire find was undertaken until 1970, after Presbyterian Robinson, director of Claremont (Calif.) Graduate School's Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, got UNESCO to assemble a team for the painstaking process of piecing together and editing the 1,191 surviving pages. The first of eleven volumes of an English translation appeared” in 1975. [Source: Time, June 9, 1975 ++]

Elaine H. Pagels wrote: “There were 52 texts altogether, apparently, unless some of them were burned that we don't know about. And they contain, some of them, secret gospels, such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip. The Gospel of Mary Magdalene is a similar text that was found separately. They also contain conversations between Jesus and his disciples.... All kinds of literature from the early Christian era, a whole discovery of text rather like the New Testament but also very different. [Source:Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Mariane Bonz wrote: “The collection, now known as the Nag Hammadi Library, is of great importance for the understanding of the development of early Christian communities because it presents the social and religious perspectives of groups of Christians who did not prevail in the battles that eventually resulted in the formation of a single, unified church. Their differences with more orthodox Christians covered a wide range of issues, including whether Jesus' death on the cross was either real or relevant, and whether women were among Jesus' true disciples and, therefore, had the authority to teach and to baptize. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Before the emergence of the Nag Hammadi texts, the views expressed in such early Christian writings as the Gospel of Mary, the Apocryphon (secret teaching) of John, and the Dialogue of the Savior were known only from the distorted descriptions found in the writings of their opponents. Since these opponents were famous church leaders such as Irenaeus, Hippolytus, and Tertullian, it is not surprising that their writings were not preserved by the church. Because of the discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library, modern Christians have a much more complete picture of their spiritual family tree.

“The common thread that unites the disparate writings of the Nag Hammadi collection is an emphasis on secret, saving knowledge (gnosis), as well as an other worldly estrangement from human society in general and a desire to withdraw from the corruption of the material world. James Robinson likens the spirit of these writings to the counter-culture movements begun in the 1960s: disinterest in the goods of a consumer society, withdrawal into communes of the like-minded. . . sharing an in-group's knowledge, both of the disaster-course of the [mainstream] culture and of an ideal, radical alternative. . . .This is the real challenge rooted in such materials as the Nag Hammadi library.

Discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library

Mariane Bonz wrote: “As was the case with the Dead Sea Scrolls, the discovery of the literary treasures of Nag Hammadi was largely accidental. Several hundred miles south of Cairo, where the Nile River bends sharply east, beyond the ancient monastery of Pachomius at Chenoboskion, a group of local farmers were digging up the rich soil surrounding the river bed to use as fertilizer for their crops. One of these farmers, Mohammed Ali, happened upon a large storage jar. Hoping that it might contain gold or an equally precious coin hoard, he broke open the jar. Out tumbled twelve large, leather-bound codices. The year was 1945, two years before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Professor Elaine H. Pagels told PBS: “Mohammed Ali going with his brothers on an ordinary errand. They saddled up their camels and they rode out from their village, a small town in the barren stretches of upper Egypt. They took their camels and rode up to a cliff nearby, which is honeycombed with thousands of caves. These caves were used as burial caves in antiquity, thousands of years ago. But they were digging under the cliffs for fertilizer, that is, for bird droppings which fertilized the crops. And Mohammed Ali said he struck something when he was digging underground. And, curious, he kept digging, and he was startled to find a six foot jar sealed. And next to it was buried a corpse. [Source: Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Mohammed Ali said he hesitated to break the jar because he thought there might be a jinn in it. But hope overcame fear; he said he picked up his mattock and smashed the jar, and saw particles of gold fly out of it, much to his delight. But a moment later he realized it was only fragments of papyrus. Inside the jar were 13 volumes, bound in tooled gazelle leather. Thirteen volumes of papyrus text. Now Mohammed Ali could not read these texts. He doesn't read Arabic, which is his own language. And these texts were in some strange archaic language. They were actually Coptic, which is the Egyptian language of 1400 years ago. But he nevertheless put them in his backpack, slung them along and took them home and threw them on the ground in his house near the stove. Later his mother said that she took some of them and threw them into the fire for kindling when she was baking bread. What we didn't know until much later is that these contained some of the most precious texts of the 20th century. That they have uncovered for us a whole new way of seeing the early Christian world.

Bonz wrote: “Mohammed gave one of the books to his brother-in-law Raghib, who eventually sold it to a Cairo museum. Of the remaining eleven books, one was partially burned by Mohammed's wife, and the rest fell into the hands of local merchants. It took over thirty years for the Nag Hammadi codices to be recovered, collected, and edited for the public. They were finally published in English translation in 1978, thanks to the tireless efforts of James M. Robinson of the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity at Claremont Graduate School in California.

“Unfortunately, we know nothing of the history of the group who gathered together this particular collection of writings. We know only what we have been able to learn from the writings themselves. The twelve original codices each contained a number of shorter compositions or tractates, fifty-two in all. They are Coptic copies of writings that were originally composed in Greek. (Coptic is a version of the ancient Egyptian language adapted to the Greek alphabet that was in use in Egypt during the early Christian period.) These writings cover a wide variety of subjects, and they seem to have been composed originally by a number of different authors, at different times, and in a variety of locations.

Contents of and Books About the Nag Hammadi Library

This immensely important discovery includes a large number of primary "Gnostic Gospels" – texts once thought to have been entirely destroyed during the early Christian struggle to define "orthodoxy" – scriptures such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Truth. Many scriptures in the Nag Hammadi collection were influenced by Valentinus (c. 100–160 AD) and his tradition of Gnosis. The discovery and translation of the Nag Hammadi library, initially completed in the 1970's, has provided impetus to a major re-evaluation of early Christian history and the nature of Gnosticism. [Source: Gnostic Society]

According to the Gnostic Society: “For an introduction to the Nag Hammadi discovery and the texts in this ancient library, first, read an excerpt from Elaine Pagels' excellent popular introduction to the Nag Hammadi texts, The Gnostic Gospels. Then, for an overview of the Gnostic scriptures and a discussion of ancient Gnosis, read this excerpt from Dr. Marvin Meyer's introduction to The Gnostic Bible. For another brief general overview, we offer an Introduction to Gnosticism and the Nag Hammadi Library by Lance Owens. [Source: Gnostic Society]

The Nag Hammadi Scriptures, edited by Marvin Meyer and published in 2007, provides authoritative translations for all of the Nag Hammadi texts, along with introductions and notes on the translations. We also highly recommend The Gnostic Bible, edited by Willis Barnstone and Marvin Meyer; this comprehensive volume includes excellent introductory material and provides beautiful translations for the most important Nag Hammadi scriptures.

All the texts discovered at Nag Hammadi are available in the Gnostic Society Library; the collection is indexed in alphabetical order, and by location in the original codices. For many of the major writings in the Nag Hammadi collection more than one translation is provided in our library. If you would like to see the ancient manuscripts themselves, digital images of the original Nag Hammadi Codices are available online at the Claremont Colleges Digital Library.

Important Nag Hammadi Scriptures

Gospel of Mary

According to the Gnostic Society: “ When analyzed according to subject matter, there are roughly six separate major categories of writings collected in the Nag Hammadi codices: 1) Writings of creative and redemptive mythology, including Gnostic alternative versions of creation and salvation: The Apocryphon of John; The Hypostasis of the Archons; On the Origin of the World; The Apocalypse of Adam; The Paraphrase of Shem. (For an in-depth discussion of these, see the Archive commentary on Genesis and Gnosis.) [Source: Gnostic Society]

2) “Observations and commentaries on diverse Gnostic themes, such as the nature of reality, the nature of the soul, the relationship of the soul to the world: The Gospel of Truth; The Treatise on the Resurrection; The Tripartite Tractate; Eugnostos the Blessed; The Second Treatise of the Great Seth; The Teachings of Silvanus; The Testimony of Truth. 3) “Liturgical and initiatory texts: The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth; The Prayer of Thanksgiving; A Valentinian Exposition; The Three Steles of Seth; The Prayer of the Apostle Paul. (The Gospel of Philip, listed under the sixth category below, has great relevance here also, for it is in effect a treatise on Gnostic sacramental theology). ^

4) “Writings dealing primarily with the feminine deific and spiritual principle, particularly with the Divine Sophia: The Thunder, Perfect Mind; The Thought of Norea; The Sophia of Jesus Christ; The Exegesis on the Soul. 5) Writings pertaining to the lives and experiences of some of the apostles: The Apocalypse of Peter; The Letter of Peter to Philip; The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles; The (First) Apocalypse of James; The (Second) Apocalypse of James, The Apocalypse of Paul. 6) Scriptures which contain sayings of Jesus as well as descriptions of incidents in His life: The Dialogue of the Saviour; The Book of Thomas the Contender; The Apocryphon of James; The Gospel of Philip; The Gospel of Thomas. ^

“This leaves a small number of scriptures of the Nag Hammadi Library which may be called "unclassifiable." It also must be kept in mind that the passage of time and translation into languages very different from the original have rendered many of these scriptures abstruse in style. Some of them are difficult reading, especially for those readers not familiar with Gnostic imagery, nomenclature and the like. Lacunae are also present in most of these scriptures – in a few of the texts extensive sections have been lost due to age and deterioration of the manuscripts. ^

“The most readily comprehensible of the Nag Hammadi scriptures is undoubtedly The Gospel of Thomas, with The Gospel of Philip and the The Gospel of Truth as close seconds in order of easy comprehension. (Thankfully, these texts were all very well preserved and have few lacunae.) There are now several published editions and translations of most of these scriptures available; the standard complete edition is the The Nag Hammadi Scriptures, edited by Marvin Meyer, published in 2007.” ^

List of Nag Hammadi Texts

Complete list of codices found in Nag Hammadi

Gospel of Phillip

Codex I (also known as The Jung Codex):

The Prayer of the Apostle Paul

The Apocryphon of James (also known as the Secret Book of James)

The Gospel of Truth

The Treatise on the Resurrection

The Tripartite Tractate

Codex II:

The Apocryphon of John

The Gospel of Thomas a sayings gospel

The Gospel of Philip

The Hypostasis of the Archons

On the Origin of the World

The Exegesis on the Soul

The Book of Thomas the Contender

Codex III:

The Apocryphon of John

Holy Book of the Great Invisible Spirit named The Gospel of the Egyptians

Eugnostos the Blessed

The Sophia of Jesus Christ

The Dialogue of the Savior

Codex IV:

The Apocryphon of John

Holy Book of the Great Invisible Spirit named The Gospel of the Egyptians

Codex V:

Eugnostos the Blessed

The Apocalypse of Paul

The First Apocalypse of James

The Second Apocalypse of James

The Apocalypse of Adam

Codex VI:

The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles

The Thunder, Perfect Mind

Authoritative Teaching

The Concept of Our Great Power

Republic by Plato - The original is not gnostic, but the Nag Hammadi library version is heavily modified with then-current gnostic concepts.

The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth - a Hermetic treatise

The Prayer of Thanksgiving (with a hand-written note) - a Hermetic prayer

Asclepius 21-29 - another Hermetic treatise

Codex VII:

The Paraphrase of Shem

The Second Treatise of the Great Seth

Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter

The Teachings of Silvanus

The Three Steles of Seth

Satellite view of Nag Hammadi, source of the Nag Hammadi texts

Codex VIII:

Zostrianos

The Letter of Peter to Philip

Codex IX:

Melchizedek

The Thought of Norea

The Testimony of truth

Codex X:

Marsanes

Codex XI:

The Interpretation of Knowledge

A Valentinian Exposition, On the Anointing, On Baptism (A and B) and On the Eucharist (A and B)

Allogenes

Hypsiphrone

Codex XII

The Sentences of Sextus

The Gospel of Truth

Fragments

Codex XIII:

Trimorphic Protennoia

On the Origin of the World

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024