Home | Category: The Gospels and Early Christian Texts

TRANSLATIONS OF THE BIBLE

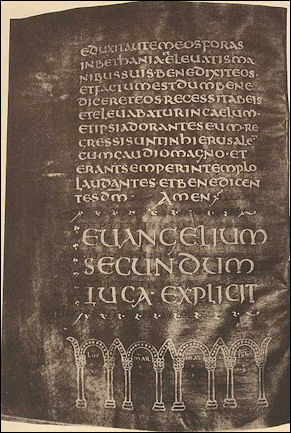

Luke Codex Brixianus The original Old Testament was written in Hebrew. The Torah, or Hebrew Bible, used by Jews today is a 10th century translation of Greek translation which in turn was based on translations of Hebrew and Aramaic text. By the A.D. 1st century few Jews — which by that time had been dispersed around the Mediterranean — spoke Hebrew anymore. Aramaic was the dominant language in Palestine while Greek had been the language of culture since Alexander the Great conquests in the 4th century B.C.

Many modern translations of the Christian Bible are based on Greek translations of the Hebrew original. The Septuagint is a famous Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible made in the 3rd century B.C. It contains 13 documents not included in the original Hebrew Bible. The Septuagint became the Old Testament for Christians.

The Septuagint (from Latin for “70") is so named because according to tradition it was assembled by 72 Jewish translators called to Alexandria by the Greek-Egyptian ruler Ptolemy II (285-246 B.C.) to help put it together — an assertion that appears to be untrue based on research that indicates different parts of it were written at different times in different places. In any case the Septuagint remains the authoritative Old Testament of the Orthodox and Catholic churches. From Greek not Hebrew it has been translated into Old Latin, Coptic, Armenian, Arabic and a host of other languages. Protestants have used the Hebrew Bible for its translations into vernaculars.

The Masoretic (traditional Hebrew) texts — on which English translations of the Bible are based — is in turned based on manuscripts of the Torah, the Hebrew Bible, transcribed in the beginning of the 11th century in what is known as the Leningrad Codex.

The Vulgate is the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church. It is an early translation of the Bible into Latin by St. Jerome, who lived around A.D. 400 and uses both Greek texts and Hebrew texts for his translations. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The Vulgate is a late-fourth-century translation attributed to the priest and theologian Jerome. Pope Damasus I commissioned Jerome to update the “Old Latin” (Vetus Latina) version of the Gospels used by the Roman Church. Jerome went one better, compiling a translation of the entire Bible. The influence of the Vulgate is enormous–over a thousand years later, at the Council of Trent, the Roman Catholic Church would affirm that it was the “authentic” Bible.

Many Protestant versions of the Bible have been translated into the vernacular languages of ordinary people. This tradition dates back to the time of Martin Luther. After the Diet of Worms in 1521 Luther was "abducted" by sympathetic knights and taken to Frederick the Wise's Wartburg Castle for protection. Disguised as a bearded squire he stayed there for a about year and made the most of his time translating the New Testament into vernacular German (which took only 11 weeks) and codifying his beliefs (which are the foundation of the Lutheran religion). While working on the translation Luther is said to have been tempted by the Devil and got rid of him by throwing an inkwell at him.

Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers thedailybeast.com ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Bible: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“King James Version Bible”, Black Leather-Look (imitation leather) Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Bible in English easy to read version” Amazon.com ;

“Eerdman's Dictionary of the Bible” by David Noel Eerdman Amazon.com ;

“How to Read the Bible” by James Kugel Amazon.com ;

“The New Testament in Its World: An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians” by N. T. Wright and Michael F. Bird Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Bible: The Story of the World's Most Influential Book”

by John Barton, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Who Wrote the Bible?” by Richard Friedman, Julian Smith, et al.

Amazon.com ;

“The Complete Guide to the Bible” by Stephen M. Miller Amazon.com ;

“Oxford History of the Biblical World” by Michael D. Coogan Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce Metzger and Michael D. Coogan Amazon.com

Controversy Over Bible Translations

There is a long history of controversy about translating the Word of God. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: “Among Christians, there are a variety of perspectives about the status of the Bible — whether or not it is the verbatim word of God, inerrant, divinely inspired, or just high-status ethically-significant literature. And the loftier one’s view of the Bible and its authorship is, the more problematic the question of its translation becomes. Until the end of the Middle Ages the Roman Catholic Church used the Latin Vulgate while Eastern Orthodox Churches used the Greek Byzantine text. The translation of the Bible into vernacular languages was the cause of considerable controversy. In the late fourteenth century, a number of translations of the Bible into Middle English began to circulate in England. They were attributed to Oxford scholar John Wycliffe, the founder of the Lollard movement, who was critical of the clergy and monasticism and argued that the Bible was the only reliable guide to the nature and will of God. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 05, 2016]

Wycliffe’s ideas and the translations ascribed to him (it is thought that they are the work of several hands) landed him in hot water at the Vatican, but during his lifetime he escaped relatively unscathed. It was only after his death in 1415 that he was declared a heretic. William Tyndale, a leading figure in the Protestant reformation, was not so lucky. He was executed by strangulation and subsequently burned at the stake. His translation was the first English Bible to draw directly from the Hebrew and the Greek and it became a foundational text for many other versions. Among them is the 1611 King James Bible, which continues to be viewed as the inerrant word of God by many fundamentalist Protestants.

The scandal of Biblical translation is the question of its ability to properly confer, without alteration or error, the sanctity and intent of a presumably divine author. Whatever we learned in elementary school, words have different valences in different languages. When people are pouring over a text trying to decipher a deeper meaning, those different valences become increasingly important. If a valence is present in a translation that is not in the original language, it’s effectively a mistake.

The desire for vernacular translations is easy to understand. In the Middle Ages when Roman Catholics heard the Mass and Biblical readings in Latin, only a small percentage of the congregation understood what was being read to them. Translating the Bible into the vernacular makes the Bible accessible. Perhaps emojis do the same, but it is an imprecise and almost self-consciously satirical language. To pose an overly serious question of the project, is there a theological problem with using the halo emoji to represent God?

The intention to make the Bible accessible to all can have a dark side, though. In the past two hundred years, numerous Bible translations have focused on missionary activity. Biblical translation coincided with colonialization and the imposition of both power and the culture of the translators. Numerous studies on how translation impacts communities in Africa, in South America, and among the Inuit have shown how Biblical translations often strip indigenous peoples of their autonomy and own ability to interpret. There’s a great deal of colonial interference in Biblical translation, and that leads to the imposition of Western values that sometimes have very little to do with the ancient Mediterranean world.

William Tynesdale and Early English Translations of the Bible

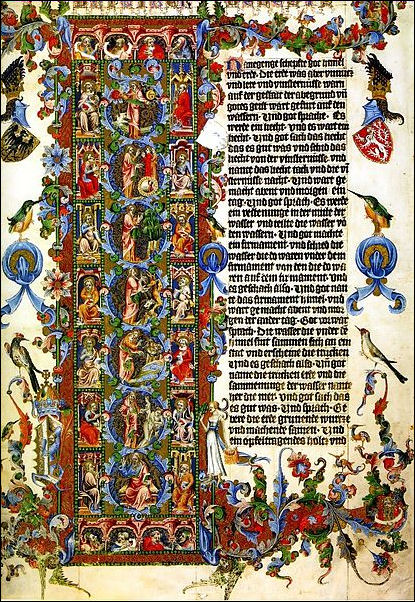

Vaclav Bible There are hundreds of translations of the Bible in English. Some of the earliest English translations were made in the 7th century date by Caedmom, the earliest English poet whose name is known. In A.D. 735 the venerable English monk St. Bede worked on a translation of the Gospel of St. John even though he was fatally ill. Upon finishing his task, it is said, he died. The first English Bible was translated from the Vulgate in 1382. It was thought to have been the work of some early scholars led by John Wycliffe. These scholars were branded as heretics because they dared to translate the word of God. These Bibles were widely circulated even though they were prohibited by Law.

Much of what we read in English Bibles today was written by William Tyndale (1494-1536), an Englishman who first translated the Bible into English from the original Greek and Hebrew texts and gave us the words and expressions: “Jehovah,” “scapegoat,” “the salt of the earth,” “Am I my brother’s keeper”,” “Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven,” and “Ask and it shall be given you. Seek and ye shall find. Knock and it shall be opened unto you.” Much of the King James Bible was derived directly or indirectly from Tyndale’s work.

Tyndale was a priest from Gloucester, England. To translate the entire Bible took him about 20 years. Because he couldn’t find anyone to publish his work in England his work was published mostly in Germany and smuggled to Britain. He too was regarded as a heretic and was threatened with being burned at the stake.

Miles Covendale produced an authorized English version of the Bible in 1535 that was based in part of Tyndale’s translation. “The Great Bible” ordered by Henry VIII in 1538 was based on Covendale’s work. One of the oldest existing Bible in the world is the Coverdale Bible. It was published in 1535 in English. Compiled by Myles Coverdale and produced in Zurich, Switzerland or Antwerp, Belgium, it is the oldest English translation of the full Bible and contains both the Old and the New Testaments. There were at least 20 editions of the Coverdale Bible, with the final edition being published in 1553. Myles Coverdale did much of the work to create early English Bibles. He made a career out of Bible printing and was involved in making other famous Bibles such as the Geneva Bible and the Great Bible.

King James Bible

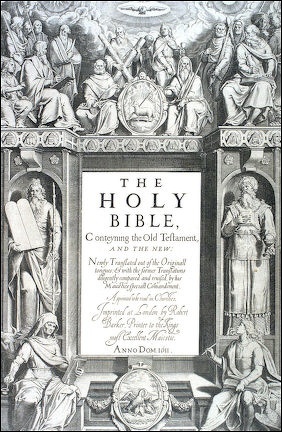

The King James Bible is one of the most popular versions of the Bible in print today. It was published in 1611, helped bring an end to the dominance of Latin as the language of Christianity and provided readers with a self-explanatory text. It was assembled by a group of 54 churchmen and scholars who met a conference at Hampton Roads. When came across problems they did their best and moved on. Much of it was derived directly or indirectly from Tyndale’s work.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The King James Version of the Bible is the most popular and influential version of the world’s most printed book. And today millions of Christians turns to the King James, or Authorized Version, of the Bible when they look for religious inspiration and guidance. It’s the Bible of choice for fundamentalist Protestants, great figures of literature, and numerous American presidents. But who is responsible for the most popular version of the Bible? And did they have any idea how influential their work would be? [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, April 29, 2018]

Adam Nicolson wrote in National Geographic: “First printed 400 years ago, it molded the English language, buttressed the “powers that be”—one of its famous phrases—and yet enshrined a gospel of individual freedom. No other book has given more to the English-speaking world...Here is the miracle of the King James Bible in action. Words from a doubly alien culture, not an original text but a translation of ancient Greek and Hebrew manuscripts, made centuries ago and thousands of miles away, arrive in a dusty corner of the New World and sound as they were meant to—majestic but intimate, the voice of the universe somehow heard in the innermost part of the ear. [Source: Adam Nicolson, National Geographic, December 2011 ]

“You don't have to be a Christian to hear the power of those words—simple in vocabulary, cosmic in scale, stately in their rhythms, deeply emotional in their impact. Most of us might think we have forgotten its words, but the King James Bible has sewn itself into the fabric of the language. If a child is ever the apple of her parents' eye or an idea seems as old as the hills, if we are at death's door or at our wits' end, if we have gone through a baptism of fire or are about to bite the dust, if it seems at times that the blind are leading the blind or we are casting pearls before swine, if you are either buttering someone up or casting the first stone, the King James Bible, whether we know it or not, is speaking through us. The haves and have-nots, heads on plates, thieves in the night, scum of the earth, best until last, sackcloth and ashes, streets paved in gold, and the skin of one's teeth: All of them have been transmitted to us by the translators who did their magnificent work 400 years ago.

Origin of the King James Bible

Title page of the first edition of the King James Bible in 1611

Adam Nicolson wrote in National Geographic: “The extraordinary global career of this book, of which more copies have been made than of any other book in the language, began in March 1603. After a long reign as Queen of England, Elizabeth I finally died. This was the moment her cousin and heir, the Scottish King James VI, had been waiting for. Scotland was one of the poorest kingdoms in Europe, with a weak and feeble crown. England by comparison was civilized, fertile, and rich. When James heard that he was at last going to inherit the throne of England, it was said that he was like "a poor man?…?now arrived at the Land of Promise." [Source: Adam Nicolson, National Geographic, December 2011 ]

“In the course of the 16th century, England had undergone something of a yo-yo Reformation, veering from one reign to the next between Protestant and anti-Protestant regimes, never quite settling into either camp. The result was that England had two competing versions of the Holy Scriptures. The Geneva Bible, published in 1560 by a small team of Scots and English Calvinists in Geneva, drew on the pioneering translation by William Tyndale, martyred for his heresy in 1536. It was loved by Puritans but was anti-royal in its many marginal notes, repeatedly suggesting that whenever a king dared to rule, he was behaving like a tyrant. King James loved the Geneva for its scholarship but hated its anti-royal tone. Set against it, the Elizabethan church had produced the Bishops' Bible, rather quickly translated by a dozen or so bishops in 1568, with a large image of the Queen herself on the title page. There was no doubt that this Bible was pro-royal. The problem was that no one used it. Geneva's grounded form of language ("Cast thy bread upon the waters") was abandoned by the bishops in favor of obscure pomposity: They translated that phrase as "Lay thy bread upon wette faces." Surviving copies of the Geneva Bible are often greasy with use. Pages of the Bishops' Bible are usually as pristine as on the day they were printed.

“This was the divided inheritance King James wanted to mend, and a new Bible would do it. Ground rules were established by 1604: no contentious notes in the margins; no language inaccessible to common people; a true and accurate text, driven by an unforgivingly exacting level of scholarship. To bring this about, the King gathered an enormous translation committee: some 54 scholars, divided into all shades of opinion, from Puritan to the highest of High Churchmen. Six subcommittees were then each asked to translate a different section of the Bible.

Compilers of the King James Bible

Adam Nicolson wrote in National Geographic: “Although the translators were chosen for their expertise in the ancient languages (none more brilliant than Lancelot Andrewes, dean of Westminster), many of them had already enjoyed a rich and varied experience of life. One, John Layfield, had gone to fight the Spanish in Puerto Rico, an adventure that left him captivated by the untrammeled beauty of the Caribbean; another, George Abbot, was the author of a best-selling guide to the world; one, Hadrian à Saravia, was half Flemish, half Spanish; several had traveled throughout Europe; others were Arab scholars; and two, William Bedwell and Henry Savile, a courtier-scholar known as "a magazine of learning," were expert mathematicians. There was an alcoholic called Richard "Dutch" Thomson, a brilliant Latinist with the reputation of being "a debosh'd drunken English-Dutchman." [Source: Adam Nicolson, National Geographic, December 2011 ]

King James

“Among the distinguished churchmen was a sad cuckold, John Overall, dean of St. Paul's, whose friends claimed that he spent so much of his life speaking Latin that he had almost forgotten how to speak English. Overall made the mistake of marrying a famously alluring girl, who deserted him for a presumably non-Latin-speaking courtier, Sir John Selby. The street poets of London were soon dancing on the great man's misfortune:

“The dean of St. Paul's did search for his wife

And where d'ye think he found her?

Even upon Sir John Selby's bed,

As flat as any flounder.

“This was a world in which there was no gap between politics and religion. A translation of the Bible that could be true to the original Scriptures, be accessible to the people, and embody the kingliness of God would be the most effective political tool anyone in 17th-century England could imagine. "We desire that the Scripture may speake like it selfe," the translators wrote in the preface to the 1611 Bible, "that it may bee understood even of the very vulgar." The qualities that allow a Brother Rome Wager to connect with his cowboy listeners—a sense of truth, a penetrating intimacy, and an overarching greatness—were exactly what King James's translators had in mind.

“They went about their work in a precise and orderly way. Each member of the six subcommittees, on his own, translated an entire section of the Bible. He then brought that translation to a meeting of his subcommittee, where the different versions produced by each translator were compared and one was settled on. That version was then submitted to a general revising committee for the whole Bible, which met in Stationers' Hall in London. Here the revising scholars had the suggested versions read aloud—no text visible—while holding on their laps copies of previous translations in English and other languages. The ear and the mind were the only editorial tools. They wanted the Bible to sound right. If it didn't at first hearing, a spirited editorial discussion—extraordinarily, mostly in Latin and partly in Greek—followed. A revising committee presented a final version to two bishops, then to the Archbishop of Canterbury, and then, notionally at least, to the King.

Struggles and Methods Used in Making of the King James Bible

King James I of England commissioned more than 40 translators to produce an accurate vernacular translation of the Greek and Hebrew texts. Those translators divided into “companies” that worked on various sections of the Bible and then reconvened to collate and revise their translations. How they actually translated the Bible has always been shrouded in mystery. According to some fundamentalist Christians, these translators were guided by the Holy Spirit and miraculously agreed on the wording of the text. Biblical scholars and historians, including evangelical Christian scholars, have been pushing back against this view for over a century. But the discovery of new manuscripts in the archives of some of Europe’s oldest libraries is shedding light on how the KJV came to be, with some surprising results. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, April 29, 2018]

French scholar Isaac Casaubon and English translator John Bois were two of the 40 translators involved in the project. In trying to produce accurate translations that made sense of the Greek, Bois and Causaubon used methods that today would be called “historical-critical.” They struggled with inconsistencies in the chronology of books of the Hebrew Bible and used Greek literature to deduce the meaning and function of passages of the Bible. In their correspondence Bois points to an article Causabon had written on riddles in Greek literature as a parallel to a passage in the Old Testament apocrypha (a part of the King James Version people often don’t know exists). That they are using historical methodologies is stunning; not only because we tend to associate these techniques with the Enlightenment period and the rise of science, but also because, today, conservative fundamentalists consider these methods to be an attack on the Bible itself.

Contrary to the mythology that persists among some “King-James-Only” Christians today, far from producing identical texts, the translators of the KJV disagreed with one another and wrestled with textual issues all the way into the final stages of revising the King James Version. Dr. Nicholas Hardy, an early modern scholar at the University of Birmingham, and expert on the King James Bible, told The Daily Beast, was much more confused than is usually thought: “people were drafted in very late in the process, they disagreed with each other a lot and reached awkward compromise solutions.” All of the confusion is one of the reasons that the KJV was revised so many times. The modern version is based on the 1769 revision.

Success of the King James Bible

Adam Nicolson wrote in National Geographic: “The new translation of the Bible was no huge success when it was first published. The English preferred to stick with the Geneva Bibles they knew and loved. Besides, edition after edition was littered with errors. The famous Wicked Bible of 1631 printed Deuteronomy 5:24—meant to celebrate God's "greatnesse"—as "And ye said, Behold, the Lord our God hath shewed us his glory, and his great asse." The same edition also left out a crucial word in Exodus 20:14, which as a result read, "Thou shalt commit adultery." The printers were heavily fined. [Source: Adam Nicolson, National Geographic, December 2011 ]

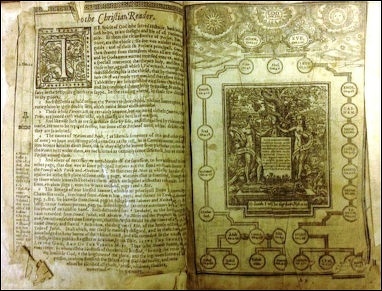

Second oldest King James Bible, from 1612

“But by the mid-1600s the King James had effectively replaced all its predecessors and had come to be the Bible of the English-speaking world. As English traders and colonists spread across the Atlantic and to Africa and the Indian subcontinent, the King James Bible went with them. It became embedded in the substance of empire, used as wrapping paper for cigars, medicine, sweetmeats, and rifle cartridges and eventually marketed as "the book your Emperor reads." Medicine sent to English children during the Indian Mutiny in 1857 was folded up in paper printed with the words of Isaiah 51 verse 12: "I, even I, am he that comforteth you." Bible societies in Britain and America distributed King James Bibles across the world, the London-based British and Foreign Bible Society alone shipping more than a hundred million copies in the 80 years after it was founded in 1804.

“The King James Bible became an emblem of continuity. U.S. Presidents from Washington to Obama have used it to swear their oath of office (Obama using Lincoln's copy, others, Washington's). Its language penetrated deep into English-speaking consciousness so that the Gettysburg Address, Moby Dick, and the sermons and speeches of Martin Luther King are all descendants of the language of the English translators.

“But there was a dark side to this Bible's all-conquering story. Throughout its history it has been used and manipulated, good and bad alike selecting passages for their different ends. Much of its text is about freedom, grace, and redemption, but those parts are matched by an equally fierce insistence on vengeance and control. As the Bible of empire, it was also the Bible of slavery, and as such it continues to occupy an intricately ambivalent place in the postcolonial world.

“Pious Rastafarians read the King James Bible every day. Lorne has read it "from cover to cover." Evon Youngsam, who is a member of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, a Rastafarian "mansion" in Kingston, its headquarters opposite Bob Marley's old house in the city, learned to read with the King James Bible at her grandmother's knee. She taught her own children to read with it, and they, now living in England, are in turn teaching their children to read with it. "There is something inside of it which reaches me," she says, smiling, the Bible in her hand, its pages marked with blue airmail letters from her children on the other side of the ocean.”

Devil’s Bible?

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast, What is the secret to the longevity and brilliance of the largest surviving medieval manuscript? Lucifer himself is said to have made it. We have all heard that the Bible is the Word of God—but what if it were actually the work of Satan? Sure, there are various heretical groups throughout history that have thought that parts of the Bible were false, but in the case of the world’s largest surviving medieval manuscript some believe that Satan himself is the book’s scribe. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, May 29, 2016 /=/]

Devil's Bible

“While the technical name for the manuscript is Codex Gigas (literally “giant book” in Latin), it is better known as the ‘Devil’s Bible.’ It is currently housed in the National Library in Stockholm, but it was created in the twelfth century in Bohemia (the modern Czech Republic), possibly at the Benedictine monastery of Podlažice. It was transported to Sweden as part of the booty seized at the conclusion of the Thirty Years’ war in 1648. It would have taken two men to steal it, as the book is around a meter tall and weighs almost 165 pounds. /=/

“It’s not just the scale of the book that make it unusual, but also its contents. In addition to the Vulgate (the Latin version of the Bible), it contains a copy of the Jewish historian Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities, Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies, ancient medical texts, and a copy of The Chronicle of Bohemia by Cosmas of Prague (1050). Ten pages are missing, however, and as all of the works contained in the codex are complete, there’s some speculation about what they contained. Some say they held a transcription of a prayer to Satan, while scholars—the spoilsports—hypothesize they held the rules of the monastic community from which the book originated. /=/

“It is known as the Devil’s Bible for two reasons. The first is apparent to anyone who visits it: the recto of folio 290 (that’s the reverse side of the 290th leaf in the book) is blank except for a large half-meter tall illustration of the devil. The Devil is pictured with a green face, talons, and horns, crouching in a squat, almost as if he were in a yoga pose. /=/

“The second reason for its name is due to the story of its composition. According to legend, the enormous book was the work of a single monk who had been sentenced to death by inclusion (being walled up alive). In an effort to delay or forestall his execution, the monk promised to produce in a single night a manuscript that would bring glory to the monastery. The task, it is said, was too enormous, and he turned to Satan for help. The Devil completed the manuscript, presumably in exchange for the monk’s soul, and out of gratitude to Satan the monk added the large illustration of the Prince of Darkness. The monk survived but became remorseful and turned to the Virgin Mary, asking her for help. The Virgin agreed, but just as he was on the verge of being freed from his pact, he died. /=/

“Legend has it that ill fortune befalls anyone who possesses the manuscript. A nineteenth-century collection of anecdotes tells a macabre version of Night at the Museum in which a porter at the national library where the book was housed was locked in for the night after falling asleep in the main reading room. When he woke up he saw the books moving around of their own accord and dancing. A large broken clock suddenly sprang back to life and started to chime the hours. In the morning the porter was found crouched under a table in terror and spent the rest of his days in an asylum. /=/

Scientific testing of the book revealed that it does appear to be the work of a single scribe: the handwriting is remarkably consistent and uniform throughout. As you might expect, it’s unlikely to have been produced in a single night: a National Geographic study concluded that a single person working 24 hours a day (without the help of a malevolent demon) would take five years to complete it. Assuming that that person also ate and slept, it is estimated that it would take approximately 25-30 years to complete. /=/

“The origins of the story of the monk who sold his soul to the Devil are unknown, but it is remarkably similar to the medieval tale of Theophilus the Penitent. Theophilus was a sixth-century archdeacon who, with the help of a necromancer, made a pact with the devil that allowed him to become bishop. He later repented of his decision, beseeched the Virgin Mary for help, fasted for seventy-three days, and died (from joy, or perhaps starvation) once his contract with the Devil was burned. /=/

“The story was popular in medieval art from the eleventh century onward and served as the inspiration for the legend of Dr. Faustus. And it’s likely that the same thing has happened with the Devil’s Bible. The application of this legend to Codex Gigas is really a sign of how inspiring the book is: it is so remarkable that people imagined that it must have been made with supernatural help. /=/

“Satanic inspiration doesn’t stop here. There are numerous other pieces of art for which he is rumored to have served as a muse. While he has yet to receive a shout-out in an Academy Award speech, rumors of demonic influence often surround exceptional pieces of work. For example, in 1713 the composer Giuseppe Tartini told a friend that his Sonata in G minor was composed after a dream in which he made a pact with the devil. In the dream, he handed the Devil his violin and the Prince of Darkness began to play a haunting melody. Tartini awoke and recaptured the melody on his violin, dubbing it the Devil’s Trill. The Sonata was Tartini’s favorite, but he said that it was vastly inferior to the one he heard playing in his dream.” /=/

Modern Translations of the Bible

The Devil in the Devil's Bible

There are about 900 English translations of the Bible. The trend in recent years has been to produce Bibles that are easy to read and understand and are full of modern idioms. These include a hip-hop version called “ Rappin With Jesus” . One version by the American Bible Society has Jesus being wrapped "in baby clothes" and laid in "a bed of hay" instead of wrapped "in swaddling clothes" and laid in "a manger." There is also a “Complete Idiot’s Guide to the Life of Christ” and a “Complete Idiot’s Guide to Understanding Judaism.”

The emoji Bible (subtitled “Scripture 4 Millenials”) a 3,300-page translation of the King James Version of the Bible became available on the iTunes store for $2.99 in June 2016. A politically-correct version of the Bible refers to God as the "Parent" rather "Father" and starts the Lord prayer with "Father, Mother." The book calls Jesus the "child" of God rather than the "son" of God. References to "darkness" (an affront to Blacks) and right-handedness have also been removed.

Religious publishing is big business backed by skillful marketers that produced things like waterproof outdoor Bibles for cowboys and camouflage version for war zones as well as Jesus dolls that recite passages, Bible bingo games and coloring books, Bible-zines for teenagers; and the — God’s Little Princess Devotional Bible — for four-year-old girls. Such materials are nothing new. A comic-book-like version of the Bible, called “ Bible for the Poor” , was printed during the Reformation.

The scholar Robert Alter has called the tendency to modernize the language of Bible a "trap" because the original Hebrew Bible had "spare and verb-centered diction," which "has a unique feel that is not easily captured in a modern tongue" and "is quite varied in style and sometimes unclear."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Bible Development Timelines, Relevancy 22 and New Testament Canon, Bible Diagrams

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024