Home | Category: Early History of Christianity / Early Christian Theology, Councils and Practices

FIRST COUNCIL OF NICAEA IN A.D. 325

First Council of Nicaea In A.D., 325, the Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea (present-day Iznik In Turkey), inaugurating the ecumenical movement. Called by Constantine to combat heresy and settle questions of doctrine, it attracted thousands of priests, 318 bishops, two papal lieutenants and the Roman Emperor Constantine himself. The attendees discussed the Holy trinity and the eventual linkage of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, argued whether Jesus was truly divine or just a prophet (he was judged divine), and decided that Easter would be celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox.

Nicaea is not far from Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). After originally being scheduled to meet in Ancyra (also in Turkey), the council was moved to Nicaea, where 318 bishops met in June 325 A.D. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In the ancient world, Nicaea was a locus for commerce and politics. It was part of the Roman province of Bithnyia and Pontus and competed with rival city Nicomedia for the seat of the Roman governor (a kind of ancient capital city). Though it was sacked in the third century, by the fourth century it had again risen to prominence as a military and administrative center for the eastern part of the Roman empire. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, Sep. 15, 2018]

In 325 A.D,, following decades of tense and heated theological debate, the emperor Constantine convened a meeting of bishops in Nicaea to decide upon the central religious debates of the day. Constantine, like other Roman emperors and administrators, was a strong believer in the principles of unity and uniformity. Theological disagreements about the nature of the relationship between Jesus and God the Father had already bubbled into public controversy in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, and Constantine wanted to put an end to the discord, which he saw as fractious and divisive. There had been Church councils before Nicaea, but this was the first that endeavored to reach a consensus by involving global representatives. According to the Christian historian Sozomen, Constantine had Hosius of Cordoba (in Spain) invite the “most eminent men of the churches in every country.”

The Council of Nicaea gave us the Roman version of Christianity rather the Nestorian. The most important decision was the rejection of Arius’s arguments and the adoption of Nicene creed: the assertions that Christ’s divinity, the Virgin Birth and the Holy Trinity were truths and the denial of Christ’s divinity was a heresy. This became the basis of all church doctrine from that time forward. Anyone who departed from the creed was branded a heretic.

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “The first of the ecumenical councils held at Nicea in 325 A.D. has ever aroused the interest of historians and theologians alike. Not only did it establish the precedent for conciliar authority in the Church, but it also introduced the mixed blessing of imperial patronage and control. The bishops who attended did so at imperial command and expense, and its decrees were enforced with imperial assistance. Despite the evils attendant upon this precedent, the council's great importance lay in its decrees against Arianism, the first of the great heresies, an aberation of the Gospel which cut out the very heart of Christianity. Since indeed this heresy reappears among us in subtler forms in every generation, we do well to reconsider the actions of our Fathers who first met this foe and expelled it from the Church. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu]

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Decoding Nicea: Constantine Changed Christianity and Christianity Changed the World”

by Paul Pavao, Alan Sisto, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea” by Young Richard Kim Amazon.com ;

“The Seven Ecumenical Councils” by Henry R Percival, Philip Schaff, et al Amazon.com ;

“The General Councils: A History of the Twenty-One Church Councils from Nicaea to Vatican II by Christopher M. Bellitto Amazon.com ;

“The Church and the Roman Empire (301–490): Constantine, Councils, and the Fall of Rome” by Mike Aquilina Amazon.com ;

“The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire” by Alan Kreider Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Great” by Michael Grant Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Great: And the Christian Revolution” by G. P. Baker Amazon.com ;

“When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers” by Marcellino D'Ambrosio Amazon.com ;

“Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers” by Andrew Louth and Maxwell Staniforth Amazon.com ;

“Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years” by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Walter Dixon, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

Reasons the First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325 Was Held

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “The Council of Nicea, which took place in 325, was a response to a crisis that developed in the church over the teachings of a presbyter, or priest, of the church in Alexandria. And his teachings suggested that Jesus was not fully divine, that Jesus was certainly a supernatural figure of some sort, but was not God in the fullest sense. His opponents included a fellow who came to be bishop of Alexandria, Anthanasius, and the folk on that side of the divide insisted that Jesus was fully divine. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

The Council of Nicea was called to try to mediate that dispute, and the Council did come down on the side of the full divinity of Jesus. It all boils down to one iota of difference. And the debates in the 4th century about the status of Jesus have to do with the Greek word that exemplifies the problem. One party said that Jesus was homo usias with the father, that is of the same being or substance as the father. The other party, the Arian party, argued that Jesus was homoi usias with the father, inserting a single letter "i" into that word. So the difference between being the same and being similar to was the heart of the debate over Arianism. And the Council of Nicea resolved that the proper teaching was that Jesus was of the same being as the father.

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “For almost three centuries the Church had been suffering persecution until Constantine, by the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, declared equal toleration for all religions in the empire. During the 300 years of persecution an ecumenical council was impossible, although scores of local synods had been held sporadically throughout the empire. The election of a new bishop required the presence of other bishops, and this opportunity was often used to discuss theological and administrative problems. With the coming of universal peace came also the possibility of a universal council, so that the edict of Constantine had a direct bearing on the convocation of the council. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu]

Major Personalities and Issues in Council of Nicea (A.D. 325)

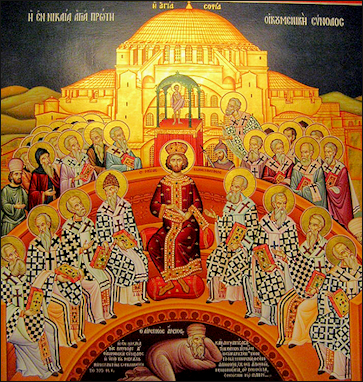

Saint Nicholas of Myra slapping Arius

The early councils were shaped largely by Christian scholars from Alexandria and their views were in line with modern Coptic doctrine that the God and Christ are of the same essence and that Christ’s divinity and humanity are unified. Constantine made a grand entrance at the council. According to one witness he “proceeded through the midst of the assembly” and acted like a Pope. The greatest debate was between Arius, a priest from Alexandria, who argued that Christ was not the equal of God but was created by him, and Athanasius, the leader of the bishops to the west, who claimed that the Father and Son, where distinct, but hatched from the same substances and thus were equal. Arus’s argument was rejected in part because it opened to the door to polytheism and a doctrine was codified that stated Christ was “begotten not made” and that God and Christ were “of the same stuff.”

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “The Emperor Constantine was the moving force in the Council and he, in effect, called it in order to solve this dispute. He did so because at that time he had just completed his consolidation of authority over the whole of the Roman Empire. Up until 324, he had ruled only half of the Roman Empire. And he wanted to have uniformity of belief, or at least not major disputes within the church under his rule. And so he was dismayed to hear of this controversy that had been raging in Alexandria for several years before his assumption of total imperial control. And in order to dampen that controversy he called the Council. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “Three important questions were agitating the minds of Christians at this time. The first problem was the practical difficulty in deciding the precise date of Easter. Different methods of calculation were in vogue in different places. This caused difficulty especially in those places where Christians from East and West were living together, as at Rome, so that some were celebrating the Ressurection while others were still observing the fast of Lent. The second problem was the Meletian schism at Alexandria. After Diocletians's persecution, Bishop Peter of Alexandria allowed those Christians who had lapsed to return to the Church after undergoing a mild penance. Meletius, also a bishop, considered the terms too mild, and he rebelled by ordaining some of his own supporters, whereupon he was excommunicated by Peter. Meletius founded his own church with his own clergy. He wanted a purer church composed only of those stalwarts who had not lapsed in persecution. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

The third problem was Arianism, a theological issue. Arius was a priest from the suburbs of Alexandria, who was also a supporter of Meletius against the Bishop of Alexandria. He recognized the difficulty of accepting three co-equal Persons in the Godhead, and of believing that it was truly God who became Incarnate. Since he was dealing with many pagans in the vicinity of the university, the first thing he wanted was to get them to accept monotheism and to deny polythesim. The notion of the Trinity seemed to him nothing more than a revived polythesim. The Son was therefore a creature, said Arius, the first-born to be sure, but inferior to God nonetheless. A characteristic phrase of the Arians was "There was a time when He (the Son) was not." =

“The effect of Arius' teaching was to produce a piece of mythology. The personal unity of the Supreme God might be retained, but Christ belonged to no order of being that the church could recognize. Since he was not perfect God but he was more than mere man, he was neither God or man, and like Mohammed's coffin, hovered between heaven and earth belonging to neither (Wand, The Four Great Heresies, p. 42). =

“Arius found himself in sharp opposition to his bishop, Alexander. The latter was supported by a rising young theologian, deacon Athanasius. They felt that if Jesus was not fully God, He could not be the savior of men. Arius was summoned before a local council in Alexandria and condemned. Constantine dispatched Bishop Hosius of Cordova to Alexandria to reconcile the factions. Meanwhile Arius had appealed to another Bishop, Eusebius of Nicomedia, who gave him full support. It was at this point that the emperor decided to call a council. Since Christianity was still largely confined to the East, the majority of bishops came from that area. Out of 318 in attendance, only 4 represented the West. The Bishop of Rome (Sylvester) sent two priests as his delegates.” =

Council of Nicaea

Proceedings of the Council of Nicea (A.D. 325)

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: When the first council was called, there was no formal doctrine of the Trinity. Christians might have broadly agreed that Jesus was God, but they disagreed about how and in what sense. The key issue was the relationship of the Son to the Father and whether or not Jesus the Son was made of the same stuff as God the Father. When the council convened, the church was an organizational mess. Attendance was a bit spotty, especially from the Western part of the empire. Even Sylvester, the bishop of Rome, sent two delegates instead of going himself. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 8, 2014]

Those who did attend disagreed with one another. People often talk about there being an Arian party, led by Arius, which thought that the Son was a creature subordinate to the Father, and a Nicene party, which thought that the Son was of the exact same substance as God and existed even before the creation of time. In fact Christianity was eveore divided than that. As Lewis Ayres shows in his book Nicaea and its Legacy, there were numerous points of disagreement and dissent. It was less of a duel and more of a WWE-styled battle royale. Much of the theological dispute might seem like hair-splitting, but the stakes were high. According to legend, Nicholas, Bishop of Myra—Santa Claus to you and me—punched out Arius rather than listen to his arguments. This might be why he tends to come and go in the dead of night, rather than stick around for those inevitable family arguments during Christmas lunch.

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “The council ran from May 30 to August 25, 325 AD. The doors of the church at Nicea were left open, however, for even pagan professors took part in some of the debates as hired lawyers, and no one wanted to run into the danger of witchcraft or demons. Many of the bishops still bore upon their bodies the scars of wounds they had suffered in the recent persecutions. At one of the early sessions Constantine shamed the Christian leaders by procucing a packet of letters he had received from many of those present, accusing others of false teaching. The emperor tore them up and threw them into the fire. It seems that the emperor himself chaired most of the sessions, and according to the procedures used in the Roman Senate, intruded himself actively in the debates. Eusebius, however, praised Constantine for the patience and fairness with which he conducted the meetings, allowing all sides to express themselves. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“There were primarily three factions at the council. On the one side were the convinced Arians, a group numbering about 20. They were determined to gain endorsement for their creed. Opposing them were the Alexandrians, led by Anthanasius and Alexander, who were equally determined that Christ's deity must in no way be compromised. The large majority of bishops comprised the middle group, of whom Robertson says, "Simple shepherds like Spyridian of Cyprus, and men of the world who were unintersted in doctrinal issues, theologians, a numerous class, who on the basis of half-understood ideas were prepared to recognize in Christ only the Mediator appointed between God and the world." On this middle party the Arians, with good reason, based their hopes of at least toleration ifnot support. When the council opened it was not at all clear that the Athanasian party would eventually win the field. =

“The only effective means of stopping the Arians was the use of the term "homousios", "of one substance (with the father)." But most of the bishops objected strenously to this term: 1) Its use had always been branded heretical by the Council of Antioch in 268 AD. 2) It opened the door to Sabellianism, which denied any distinctions at all within the godhead. It permitted men to say the Son and Father were the same. 3) Dionysius of Alexandria (d. 265) had objected to its use. It was inscriptural, that is, not found in Scripture. 4) None of the orthodox Fathers prior to Nicea, Athanasius included, had ever used the term. =

Arian Controversy

Hans A. Pohlsander of SUNY wrote: “Early in the fourth century a dispute erupted within the Christian church regarding the nature of the Godhead, more specifically the exact relationship of the Son to the Father. Arius, a priest in Alexandria, taught that there was a time when Christ did not exist, i.e. that he was not co-eternal with the Father, that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit were three separate and distinct hypostaseis, and that the Son was subordinate to the Father, was in fact a "creature." These teachings were condemned and Arius excommunicated in 318 by a council convened by Alexander, the bishop of Alexandria. But that did not by any means close the matter. Ossius (or Hosius) of Cordova, Constantine's trusted spiritual advisor, failed on his mission to bring about a reconciliation. [Source: Hans A. Pohlsander, SUNY Albany, Roman Emperors ]

“Constantine then summoned what has become known as the First Ecumenical Council of the church. The opening session was held on 20 May 325 in the great hall of the palace at Nicaea, Constantine himself presiding and giving the opening speech. The council formulated a creed which, although it was revised at the Council of Constantinople in 381-82, has become known as the Nicene Creed. It affirms the homoousion, i.e. the doctrine of consubstantiality. A major role at the council was played by Athanasius, Bishop Alexander's deacon, secretary, and, ultimately, successor. Arius was condemned.

“If Constantine had hoped that the council would settle the issue forever, he must have been bitterly disappointed. The disputes continued, and Constantine himself vacillated. Eusebius of Nicomedia, a supporter of Arius exiled in 325, was recalled in 327 and soon became the emperor's chief spiritual advisor. In 335 Athanasius, now bishop of Alexandria and unbending in his opposition to some of Constantine's policies, was sent into exile at far-away Trier.

Councils, Schisms and Branches of Christianity

Debate Between Arius and Alexander and the Nicene Creed

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The most pressing dispute concerned the teachings of a well-known priest named Arius, who was embroiled in a conflict with his bishop, Alexander of Alexandria. Contrary to many descriptions of this on the internet, both Alexander and Arius agreed that Jesus was the Son of God and God. And they agreed, on the basis of the opening to the Gospel of John, that Jesus was present for the creation of the universe. What they disagreed about was the sense in which Jesus was a God and whether or not he was equal to God the Father. Arius argued that “there was a time when [Jesus] was not.” It was a very brief moment, at the very beginning, when Jesus did not exist. This meant that Jesus was subordinate to God the Father. Alexander, for his part, maintained that Jesus and God the Father had always coexisted and were equal to one another. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, September 15, 2018]

At stake in this debate were some fundamental philosophical principles that Christianity had inherited from Greek philosophers like Plato. Each group advocated for a different word to describe the relationship between Father and Son. Arius and his supporters wanted to say that Jesus was homoiousios (of a slightly different substance than the Father) and Alexander and his supporters wanted to say that he is homoousios (of the same substance as the Father). Yes, the entire debate was over a single letter—an iota or “I”—from which we get the modern expressions “an iota of difference” and “a jot of difference.”

The debate at the council was highly contentious. According to a 14th century legend, St. Nicholas (of Santa Claus fame) actually punched Arius at one point in the proceedings. The council eventually sided with Alexander and signed a theological statement known as the Nicene Creed. The vote on the creed was not close: only 20 bishops did not vote for it and only three (Arius and his closest supporters) refused to sign it. That said, the 17 who hadn’t voted for the creed initially were eventually coerced into supporting it by the emperor. Constantine didn’t vote but oversaw the proceedings, dressed in purple.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of this moment. The Nicene Creed forms the basis for the modern creed used in churches all over the world today. You know the part that includes, “We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one being (homoousios) with the Father. Through him all things were made...”

As for Arius, he and his closest supporters were exiled from Egypt and labeled as heretics (a label that has stuck to this day). This didn’t put an end to his punishment. After his death, orthodox Christians developed harrowing stories about the gruesome nature of Arius’ death. According to his opponents, Arius died in a public toilet from a kind of explosive diarrhea that caused his intestines to exit his rectum. As Ellen Muehlberger, a professor at the University of Michigan, has shown in an article for Past and Present, this legend is about smearing the teachings of Arius with the filth of excrement. But the legend bolstered the piety of the Council of Nicaea.

Nicene Creed

The Nicene Creed goes: “We believe (I believe) in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, and born of the Father before all ages. (God of God) light of light, true God of true God. Begotten not made, consubstantial to the Father, by whom all things were made. Who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven. And was incarnate of the Holy Ghost and of the Virgin Mary and was made man; was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate, suffered and was buried; and the third day rose again according to the Scriptures. And ascended into heaven, sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead, of whose Kingdom there shall be no end. And (I believe) in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of life, who proceeds from the Father (and the Son), who together with the Father and the Son is to be adored and glorified, who spoke by the Prophets. And one holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. We confess (I confess) one baptism for the remission of sins. And we look for (I look for) the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen." [Source: J. Wilhelm, The Nicene Creed. In The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1911]

Another version goes: “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible; and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the only-begotten of his Father, of the substance of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father. By whom all things were made, both which be in heaven and in earth. Who for us men and for our salvation came down [from heaven] and was incarnate and was made man. He suffered and the third day he rose again, and ascended into heaven. And he shall come again to judge both the quick and the dead. And [we believe] in the Holy Ghost. And whosoever shall say that there was a time when the Son of God was not, or that before he was begotten he was not, or that he was made of things that were not, or that he is of a different substance or essence [from the Father] or that he is a creature, or subject to change or conversion — all that so say, the Catholic and Apostolic Church anathematizes them. [Source: The Seven Ecumenical Councils, ed. H. Percival, in the Library of Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, 2nd series (New York: Charles Scribners, 1990), Vol XIV, 3]

Conclusion of the Council of Nicea

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The council concluded with the emperor Constantine insisting that the bishops come to an agreement over the wording of the creed. He wanted peace and harmony, and in this respect he was just another Roman ruler interested in imperial unity. The eventual outcome of the council was that Arius lost by a vote of 318-3. He was denounced as a heretic and the Son was declared to be of the same exact substance (homoousios) as the Father. A clear result, a poetic creed, and most people were happy. That was that. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 8, 2014]

Except that it wasn’t. There was another council 60 years later to fine-tune the wording of the Creed, and Arius and his supporters continued to believe and preach exactly what they thought before. In sum, the Council of Nicea was less about celebrating unity than enforcing theological uniformity. In some ways it’s reassuring: when we disagree about church doctrine we can take comfort in the knowledge that if we’re not resorting to physical violence (looking at you, Santa) we’re coming out ahead.

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “Despite their hesitancy, the Fathers ultimately adopted the term "homousios". The fact that it had been suggested by the emperor may have been a factor in its acceptance. A new creed was drawn up (or that of Eusebius of Caesarea revised) incorporating the "homousios" plus a number of anathemas. Five Arians were exiled by the emperor, thereby establishing the unhappy precedent of imperial punishment of heretics, yet the bishops acquiesced in this procedure. On the other two issues, the council took a lenient view of the Meletians. Meletius himself was forbidden to exercise episcopal functions, but those whom he had consecrated were allowed to retain their status, though they were to be subject to the bishops in communion with Alexandria. On the date of Easter the council decided in favor of the usage at Rome, Italy, Africa, and the West. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“But far from settling the Arian issue, the Council of Micea ushered in the beginning of a half-century of turmoil. Once the mass of half-convinced "middle party" bishops returned home, they ignored the Nicene definition or substituted their own. After 350 AD the Arian sympathizer, Constantius, was sole ruler. By 357 AD practically the entire episcopacy of Christendom had repudiated the homoousios, though there were notable exceptions in the West who were persecuted for their stand (Athanasius, Hilary, Hosius). The period following Nicea was a bleak one for the Church, in which intrigue, double-dealing, court factions, etc. played a large role. It was due to the influence of Athanasius, the Cappadicians, and others, that a reaction set in about 360 AD. The Arians had succeeded too well, for their formula, "Christ is of another substance than the Father," went too far in the opposite direction. By the time of the second ecumenical council (Constantinople 381 AD) the Fathers were prepared to reaffirm the Nicene formulation. Our present Nicene Creed is a product of this second council.” =

Nicaea Church Where Council Was Held Found in a Lake

In 2018, archaeologists found what they believed were the long-sought remains of the church which hosted the Nicaea Council among some other Roman and Byzantine ruins underneath the surface of the lake in Iznik, Turkey. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: This was not just any archaeological discovery. They have may have chanced upon the ancient Basilica of the city of Nicaea, one of Christianity's most historic sites and the place where the Church made its first official statement about the relationship between Jesus and God. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, Sep. 15, 2018]

Historians and archaeologists had been looking for the ruins of the church for over a century. Mustafa Şahin, the current head of archaeology at Bursa Uludağ University, had been searching the shores for years before he was shown some government survey pictures. These aerial photographs clearly revealed the outline of a large church beneath the water. Dr. Şahin said, “I’d been doing field surveys in Iznik since 2006 and hadn’t yet discovered a magnificent structure like that.”

It seems likely that the remains of the church at Nicaea now lie three meters under the water in a lake. Even before the site has been excavated, local authorities have developed ambitious plans to make it accessible to tourists by constructing a submarine archaeological museum. The metropolitan mayor, Alinur Aktas, stated that professional diving classes will be available for visitors. Now, those torn between an active beach vacation with lots of scuba diving and a religious pilgrimage no longer have to choose.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024