Home | Category: Early History of Christianity / Early Christian Sects and Groups / Early Christian Theology, Councils and Practices / Christian Groups, Sects and Denominations

HERETICS

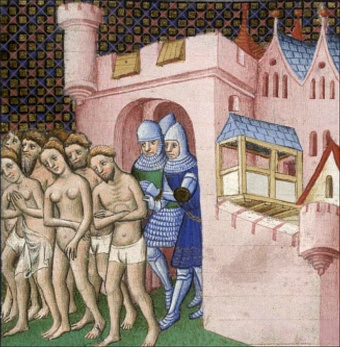

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at odds with established beliefs or customs, particularly in regards to religion. A heretic is a proponent of heresy. In Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, heresy has at times been met dealt with by excommunication or death. The most infamous death penalty for Christian heretics was being burnt at the stake.

In the early days of Christianity those who departed from the essential beliefs and moral standards of the Christian communities were known as "heretics". Their members, pastors, and bishops were not recognized by the majority of Christians, known as "Catholics."

The use of the word heresy by Christians was given wide currency by Irenaeus in his A.D. 2nd-century tract “Against Heresies”, which was used to describe and discredit his opponents during the early centuries of the Christianity. Constantine the Great christianized the Roman Empire in the 4th century with the Edict of Milan and established Christianity-based laws. The first known usage of the term heresy in a legal context was in A.D. 380 by the Edict of Thessalonica of Theodosius I. Just six years after this the first Christian heretic to be given a death sentence for offense, Priscillian, was executed in 386 by Roman secular officials for sorcery along with four or five followers. [Source: Wikipedia]

Some early heretic groups are believed to have come from Bulgaria. They discounted the Old and New Testament and didn't believe in purgatory or hell (the world was hell enough they said). They said marriage was evil and the cross was nothing but a material object. They made fun of the Redemptions and Incarnation and some even said that Christ entered the world through Mary's ear. Converted heretics wore saffron-colored crosses stitched onto their clothing and during the emotional heresy hunts hundreds of heretics were sometimes burned at a time while spectators watched. ["Life in a Medieval City" by Joseph and Frances Gies, Harper Perennial]

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Gospel According to Heretics: Discovering Orthodoxy through Early Christological Conflicts” by David E. Wilhite Amazon.com ;

“Heretics” by Ulf Bjorklund, G. K. Chesterton, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Perfect Heresy : The Revolutionary Life and Death of the Medieval Cathars”

by Stephen O'Shea Amazon.com ;

“The Lost Teachings of the Cathars: Their Beliefs and Practices” by Andrew Phillip Smith Amazon.com ;

“With Their Backs Against the Mountains: 850 Years of Waldensian Witness” by Kevin E Frederick Amazon.com

Cathars (Albigensians)

The Cathars, also known Albigensians after the town Albi, were of a group of nonviolent Christian accused of being heretics by Catholic Church. The target of the only Crusade within Europe (in 1209), they numbered about 17,000 at the beginning of the 13th century and occupied the Languedoc region of southern France that extended from the Pyrenees to the Rhone Delta. [Source: David Roberts, Smithsonian magazine]

Cathars spoke a language unrelated to French and It was rumored that the Cathars had a vast treasure and a German mystic deduced it was nothing less than the Holy Grail. Cather leaders, know as "parfaits" or "perfecti", abstained from sexual intercourse and did not marry. They were not allowed to eat meat, eggs or cheese or any other food related to animal procreation. They took no oaths but often took long fasts. Parfaits were taught to face death without fear and once it was written that "there is no more beautiful death than that of fire." There were only around 1,500 parfaits. Parfait practiced were reargued as so severe that most Cathars were "credentes" ("believers") who only became parfaits as they approached death.

Carl A. Volz wrote: “The Albigensians were divided into two classes, the Perfect or Ancients, and the Believers. The former few constituted a kind of clerical leadership. They submitted to the primary sacrament of the sect called the "consolamentum", a ceremony of initiation in which through the laying-on-of-hands the fallen soul was restored to its counterpart in heaven, its holy spirit, which would after death lead the earthly soul toward heavenly light. If the consolamentum was administered to a sick Believer who showed signs of reviving, he was encouraged to end his life by any process (the "endure") short of direct violence. The ascetic Perfecti were under obligation to propagate the faith by travelling in pairs, each man having a female companion. The Albigensians boasted 14 dioceses in France and Italy. At one time there appeared to be an Albigensian pope, when in 1167 the Albigensian Council of St. Felix-de-Caraman was presided over by an Easterner, Nicetas of Constantinople. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

Books: ; "The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy' by Steven Runciman and T"he Albigensian Heresy" (2 volumes) by H.J. Warner

History of the Cathars

Albigenian (Cather) influence became widespread in Southern France around the year 1200. Carl A. Volz wrote: “A type of Neomanichean thinking prevailed in southern France during the 12th and 13th C. Its adherents were called Albigensians at the Council of Tours in 1163, after the town of Albi, although the center of their strength was in Toulouse, Narbonne, Beziers, and Carcassonne. The wider term Cathari was also applied to them. Whatever the Albigensian relationship to the ancient Manicheans, they appeared in southern France apparently from Slavic lands where similar opinions were in vogue among the BOGOMILS and PAULICIANS. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

The populace in the valley of the Garonne had never been totally assimilated by the Catholic Franks or their successors, the Capetian kings of France. In addition to this, remnants of Jewish and Mohammedan religious influences were at work in the South. Against the drive toward French unification by the king in Paris, religious and political disaffection saw in Catharism a rallying point.

“Because the heresy presented an ecclesiastical and theological challenge, churchmen opposed it from the start. It was condemned at the Council of Toulouse in 1119, at the Second Lateran Council in 1139, and at the Council of Rheims in 1148. Pope Eugenius III dispatched Bernard of Clairvaux to preach against the Albigensians, and another Council of Rheims in 1157 condemned their majors or bishops to perpetual imprisonment. Still they flourished. Innocent III approved the newly formed Dominican Order's plans to convert them by preaching. Finally, a crusade of force was touched off by the murder of the papal legate, Peter of Castelnau, in January 1208. /~\

Cathar Beliefs

The Cathars attacked the Catholic Church as intrinsically corrupt and morally misguided and an instrument of Satan. They denied the sacraments and allowed women to become priests and give last rites. The Cathars didn't believe in marriage or baptism at birth and the only prayer they uttered was the Lord's Prayer which they recited up to 40 times.

Cathar theology was based upon Manichaean dualism. The Manichean idea of dualism divided many important things into two opposing side. To Manicheans, life can be divided neatly between good or evil, light or dark, or love and hate. Cathars believed that the Old Testament God Jehovah was actually Satan in disguise. They believed that Christ would have never have adopted a human body and thus the body and flesh of Christ never existed and Catholic rituals were fake.

Volz wrote “The Albigensians taught that the creator of the world was an evil spirit, the Demiurge or Satan, the author of the Old Testament. Men's souls, however, were created by the good God but, through the exercise of bad choices, became imprisoned in fleshly bodies. The goal of Cathar salvation consisted in the release of the soul from the body through the teachings and example of Jesus, who had come to teach man that his true nature was enslaved to the flesh and that the way of release was through asceticism. Since Christ did not truly become a man and His Passion and death were only apparent, man's redemption did not come through Christ's death. The Cathari taught a rigid morality, perpetual chastity, abstention from all animal foods, nonviolence, and general deprecation of the body. Sinners were condemned to further enfleshment through transmigration of souls.

Carcassonne — Stronghold of the Cathars

Carcassonne (50 kilometers southeast of Toulouse and 50 kilometers north of Spain) was the stronghold of the Cathars for many years. Today it is one of the most impressive giant medieval fortress in the world. Established in 1208 and rebuilt in the 19th century under the guidance of the French architect Viollet le Duc, Carscassonne isn't just a castle, it is an entire city behind a huge wall with turrets, crenelated ramparts, drawbridges and gates that reportedly inspired the setting the 1959 Disney film “Sleeping Beauty”.

Carcassonne is one of France's major tourist attractions, drawing more than two million visitors a year. From a distance, the Carcassonne fortress (known as La Cité) looks like medieval fortress as Hollywood would have created it: imposing, impregnable, and dominating the countryside around it. According to legend the Black Prince (Edward of England) took one look at it and abandoned his plans to attack it.

Murder of Saint Peter Martyr by Bellini, symbolic of the struggle with the Cathars

The oldest settlements at Carcassonne have been dated to the 6th century B.C. The Roman built a fort here in the third century to stave off Barbarian attacks and guard strategic routes from Mediterranean between the Pyrenees and the Massif Central. It was captured by the Visigoths in the 5th century and the Franks in the eighth century.

The present fortress was raised by the Cathars in the 11th century and strengthened after the Albigensian Crusade in 1209, when it was captured by forces loyal to the Catholic Church and the French monarchy. By 1240, it was regarded as impregnable and all attacks were repelled. Some of the features such as the conical roofs were added for dramatic effect by Viollet le Duc.

Albigensian Crusade

The Cathars triggered the Albigensian Crusade, the only crusade led against Europeans. Following the assassination of the papal legate in the year 1208, Pope Innocent III declared a crusade against the Albigenses. This developed into a political conflict with civil war between the north and south of France that lasted until 1229.

In late June 1209, Pope Innocent III made the call for crusaders and told all those who joined that their sins would be pardoned and that captured land would be granted to them. According to the poet and eyewitness Tudela, some 20,000 knights and 200,000 common soldiers answered the call. On July 22, 1209, the Cather stronghold of Beziers was attacked and thousands were killed.

The leader of the Albigensian Crusade, Simon de Monfort, was notorious for cutting off the noses and the upper lips of his captives to celebrate a victory. When he found 300 to 400 Cathars hiding inside he a castle he said "we burned them alive with joy in our hearts." [Source: David Roberts, Smithsonian magazine]

Volz wrote: Innocent sent his legate, Arnaud-Amalric, to preach the crusade throughout France, and Simon de Montfort was placed in charge of the military operations. In July 1209 Beziers was taken and its inhabitants massacred. Shortly thereafter Carcassonne fell. Within four years the crusaders occupied almost all the Albigensian territory, but they were unable to subdue it. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

Albigensian Crusade

“Raymond VI, despite his protestations of orthodoxy, did not match word to deed and was excommunicated. Afraid of French expansion Peter II of Aragon came in on the side of the Cathars in 1212, the same year that Simon de Montfort tried conciliation through the Statutes of Pamiers. In 1215, Prince Louis, son of the French king, Phillip II, led a futile expedition South, and the Fourth Lateran Council handed over to Simon de Montfort all the lands he had conquered as fiefs from the French king. Raymond VI was exiled, but pensioned. The council also defined orthodoxy with special reference to Albigensian errors. Two years later, in 1217, Raymond VII reconquered Toulouse, where Simon de Montfort was killed. Prince Louis remained ineffective, and after 1222, Raymond VII took over the leadership of the Southern cause.

Not until the crusade by Louis VIII in 1226, supported by the full prestige and resources of his royal office did the Albigensian cause collapse. By the Treaty of Meaux ratified at Notre Dame in Paris in 1229, Raymond VII was reconciled with the Church. Most of the southern lands were restored to him, but as fiefs of the king. After his death, Toulouse and its diocese was to revert through a marriage agreement to the King's brother. The Count also promised to pursue and punish all heretics in his domain. But the Albigensians continued to flourish, and it was their persistent growth and success which called forth the Inquisition, which immediately followed the end of the crusade. /~\

Book: "The Albigensian Crusade" by Jacques Madaule

Cathars, Dominicans and the Inquisition

The Dominican Order was founded in 1205 in order to combat the Cathar heresy. The Castilian monk, Dominic de Guzman, the future St. Dominic, came to Langedic in 1206 with a small band of followers to preach and live in poverty and fight heretics. The group was formally recognized by the Lanteran Council in 1215.

In spite of the Crusades and Dominicans the Cathars continued to survive and even thrive. In 1233 the Inquisition was set up to weed out Cathar heretics and punish them.

The Inquisition, a tool used by the Catholic to suppress heresy began in southern France and northern Italy in 1231. The more barbaric Spanish Inquisition, in which over 2,000 people were burned at the stake, began in 1483 in Spain.

The Inquisition that targeted the Cathars was led by the Dominicans. With the aid of secular authorities, it had the power to arrest anyone on the suspicion of heresy. Those accused and arrested were denied basic legal rights: they were not confronted by their accusers, they were given no legal assistance, they were interrogated in private; and the evidence was not revealed. The only thing made public was the sentence.

Anyone who was found guilty of heresy at secret Church preceding was turned over to local government officials to be burned. At the height of Inquisition a feverish woman who reportedly confessed her heresies to a priest was carried in a bed to a field and burned there, Dead Cathars were exhumed and burned

End of the Cathars

During the Inquisition many Cathars took up arms and fled to remote areas. The ruined castle of Montségur, which sits on the edge of a white limestone cliff in the Pyrenees in southern France, was the last stronghold the Cathars. Many Cathars who escaped the Inquisition gathered here and withstood a siege in 1241. After a long siege in 1244 the castle was finally taken and some 200 chained prisoners from the castle were led to a meadow below aptly named the "Field of the Burned" where they were placed on a pyre and burned alive.

After the Cathars were burned at the stake outside Montségur the remaining members of the sect hid in caves and the forest. The inquisition burned any of those found and last recorded Cather was burned at the stake in 1321. [Source: David Roberts, Smithsonian magazine]

Phillipe-Liberte was burned at the stake in the 14th century and put a curse on all those who responsible for his death and said they would die soon. The king, prosecutor and all them were dead with a year. Practitioners of underground Cathar religion later became Huguenots.

Waldensians

Burning of the Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses, Vallenses, Valdesi, and Vaudois, were followers of of an ascetic church movement that began with the Catholicism in 12th century. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon, the movement began in the Lyon and Lombardy area of France and spread to the Cottian Alps in present-day France and Italy. The founding of the Waldensians is attributed to Peter Waldo, a wealthy merchant who gave away his property around 1173.

Carl A. Volz wrote: “The first Waldensians advocated a return to the simply type of Christianity reflected in the Gospels, unencumbered with ecclesiastical organization or hierarchical structure. As contrasted with the Church, the Waldensians denied the existence of purgatory, the efficacy of indulgences and prayers for the dead. Lying was considered an especially grievous sin, and they forbade the shedding of blood and taking oaths. In an age when society was bound together by a system of feudal oaths, this prohibition was considered deleterious to the social order. Furthermore, they condemned war and capital punishment. From preaching and ex-pounding the Scriptures it was an easy transition to hearing confessions, absolving sins, and assigning penance. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu, "The Coming of the Waldensians," Great Events From History III.Comba, Emilio, History of the Waldensians of Italy from Their Origins to the Reformation. Gordon Leff, Heresy in the Later Middle Ages. Enrico Sartorio, A Brief History of the Waldensians. A.S. Turberville, Medieval Heresy and Inquisition /~]

“They divided themselves into two classes, the Perfect (Perfecti) and the Believers (Credentes). The celibate Perfecti, bound by the vow of poverty, led an itinerant life and preached. Being exempt from manual labor, they depended upon the Believers for their support. The latter group continued to live in the world as others, even receiving the sacraments, except penance, administered by Waldensian bishops. The Perfecti were further classified as bishops, priests, and deacons. Bishops celebrated the Eucharist and administered penance and ordination; priests preached and heard confessions; deacons received alms and administered the temporal affairs of the church. Bishops were elected at joint meetings of priests and deacons. One bishop, the rector, seems to have enjoyed supervision over the others, but the supreme governing power was vested in a council of all the Perfecti. /~\

History of the Waldensians

In 1173, the story goes, Peter Waldom a rich merchant in Lyons, decided to distribute his wealth to the poor and established a lay order known as the "Poor Men of Lyons, Other origins of the name suggest Vaux, or valleys of Piedmont, where the sect flourished; or Peter of Vaux, a predecessor of Waldo.

Carl A. Volz wrote: ““At first Peter's program consisted primarily of living a life of poverty, but after he became acquainted with the Bible in the vernacular he began publicly to elucidate the Scriptures. In addition, his followers openly criticized the immorality of the clergy and their frequent indifference to Christian precepts. Although Waldo's activities were not heretical, it was contrary to the Canon Law of the Church and established practice for laymen to preach.

At the Third Lateran Council (1179) the Poor Men of Lyons received authorization for their vow of poverty, and were given permission to preach provided they received authorization from local church authorities. When they found it difficult to obtain such authorization, they ignored the councils restriction by expounding the Scriptures openly in the towns. At the Council of Verona in 1184, they were condemned along with the Albigensians and expelled from Lyons. They fled to Spain, Lombardy, the Rhineland, Bohemia, Hungary, and northern France; but as they went they came into contact with more radical heretical groups who influenced them into adopting more extreme unorthodox tenets. /~\

At the Council of Verona (1184), they were accused of refusing obedience to the clergy, usurping the right of preaching, and opposing the validity of masses for the dead. Although the Waldensians did not espouse any significant doctoral aberrations, they opposed the entire sacerdotal system, declaring that the authority to exercise priestly functions was derived not from ordination but from individual merit and piety. /~\

“After their condemnation by pope Lucius III at Verona, the Waldensians scattered. Waldo led a group into upper Italy where the sect flourished in the Lombard climate of revolt and anti-clericalism. But as sporadic persecutions arose, they were gradually driven into the rugged valleys of the Piedmontese Alps. A dispute arose between the French and Italian factions in which the former, led by Waldo, rejected hierarchical organization, manual labor of the preachers, and moral requirements for one celebrating the Eucharist. The dispute reached such proportions that a majority of the sect repudiated Waldo's, leadership and followed his chief opponent, Johannes de Roncho. It appears that Waldo and the French group favored a reconciliation with Rome, whereas the Italians remained opposed to Rome. Waldo traveled through Italy and finally went to Bohemia where he died in 1217. The dispute was resolved at the Council of Bergamo (1218) in Lombardy.

During the 13th and 14th C. the center of Waldensian power shifted to Milan, where the bishop resided and a theological school grew up. Each year during Lent a council was held attended by delegates from every nation which had a Waldensian Church. Although harassed by numerous persecutions, the Waldensians persisted. In Bohemia they paved the way for John Huss, in Switzerland for Calvin, and in France they eventually merged with the Calvinists in the 17th C. The Waldensians are considered by some to be the oldest Protestant Church in existence. Some 30,000 adherents still reside in Italy today. /~\

Persecution and Massacre of Waldensians

Torture of the Waldensians

After the Reformations the Waldensians united with Protestants. Outside the Piedmont area, they joined the local Protestant churches in Bohemia, France, and Germany. After they came out of seclusion and reports were made of sedition, French King Francis I issued the "Arrêt de Mérindol", and assembled an army against the Waldensians of Provence in 1545. Eastimates of deaths in the Massacre of Mérindol ranged from hundreds to thousands, depending on the source, and several villages were destroyed. [Source: Wikipedia]

In January 1655, the Duke of Savoy ordered the Waldensians to attend Mass or relocate to the upper valleys of their homeland, giving them twenty days in which to sell their lands and move in the middle of winter. The intent was to get the Waldensians to convert to Catholicism. By mid-April, when it became clear that the Duke's efforts to force the Waldensians to conform to Catholicism had failed, he tried another approach. Under the guise of false reports of Waldensian uprisings, the Duke sent troops into the upper valleys to quell the local populace. He required that the local populace quarter the troops in their homes, which the local populace complied with. But the quartering order was a ruse to allow the troops easy access to the populace. On April 24, 1655, at 4 a.m., the signal was given for a general massacre. The Duke's forces did not simply slaughter the inhabitants. They are reported to have unleashed an unprovoked campaign of looting, rape, torture, and murder. According to one report by a Peter Liegé:

Little children were torn from the arms of their mothers, clasped by their tiny feet, and their heads dashed against the rocks; or were held between two soldiers and their quivering limbs torn up by main force. Their mangled bodies were then thrown on the highways or fields, to be devoured by beasts. The sick and the aged were burned alive in their dwellings. Some had their hands and arms and legs lopped off, and fire applied to the severed parts to staunch the bleeding and prolong their suffering. Some were flayed alive, some were roasted alive, some disemboweled; or tied to trees in their own orchards, and their hearts cut out. Some were horribly mutilated, and of others the brains were boiled and eaten by these cannibals. Some were fastened down into the furrows of their own fields, and ploughed into the soil as men plough manure into it. Others were buried alive. Fathers were marched to death with the heads of their sons suspended round their necks. Parents were compelled to look on while their children were first outraged [raped], then massacred, before being themselves permitted to die”

This massacre became known as the Piedmont Easter. An estimated 1,700 Waldensians were slaughtered. The massacre was so brutal it ignited outrage throughout Europe. Protestant rulers in northern Europe offered sanctuary to the remaining Waldensians. Oliver Cromwell, then ruler in England, began petitioning on behalf of the Waldensians. John Milton wrote the poem "On the Late Massacre in Piedmont". Swiss and Dutch Calvinists set up an "underground railroad" to bring many of the survivors north to Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024