Home | Category: Jews in the Middle Ages

JUDAISM IN THE MIDDLE AGES

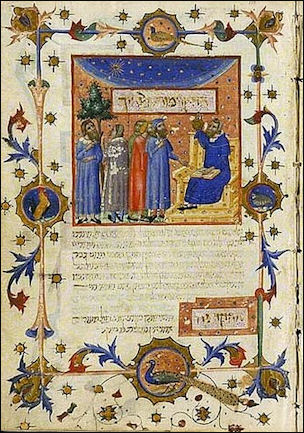

Golden Haggadah cleaning, from 1320

During the Middle Ages, many Jews lived in Christian Europe. Over time they spread from southern Europe into central and western Europe. Spain was a major center of Jewish influence. Scholars there made strides in such areas as theology and science.

As for Judaism. the Middle Ages were a time when the laws generated in the Biblical and rabbinic period were interpreted and Jews sought to understand their meanings. The process was similar to what occurred in Italy during the Renaissance, when Greek philosophy was rediscovered and applied with rigorousness and enthusiasm. Reasoning and providing rational proof were the objective with Aristotelean thought providing a primary model over the neo-Platonists. In the 16th century Jewish life was largely centered in the Kingdom of Poland-Lithuania, where a unique brand of Ashkenazi piety and learning developed, and in the Islamic world.

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Within Christian Europe, Jews developed an intellectually and spirituality vibrant culture. Communities in southern Italy, where Jews had lived since the second century B.C., were particularly creative in composing liturgical poetry in Hebrew, and they thereby laid the foundations of what was to be called the Ashkenazi rite, a term designating the Jews who lived in medieval Germany and neighboring countries. In northern France and on the eastern banks of the Rhine, important centers of rabbinical scholarship crystallized in the tenth and eleventh centuries.[Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The comprehensive commentary on the Bible and the Talmud by the French rabbi Rashi (1040–1105) continues to serve as the basic text of a traditional Jewish education. In the second half of the twelfth and in the thirteen centuries, these communities produced highly original mystical theologies, collectively known as Hasidei Ashkenaz. The Jewish communities of Provence, in southern France, and of Christian Spain witnessed not only a flowering of philosophy, biblical exegesis, and Talmudic learning but also the un-folding of a mystical literature that culminated in the composition of the Zohar ("Book of Splendor") in the thirteenth century.

On Samuel Ha-Nagid, Vizier of Granada by Abraham ibn Daud continues: “In the year 4780 [l020] he was in the palace of the King Habbus. [Samuel was already an important official before 1020.] The king had two sons: the name of the elder was Badis, and the younger, Bulukkin. All the Berber princes favored Bulukkin, the younger son, as the successor, but all the rest of the people favored Badis. The Jews, too, and among them Rabbi Joseph ibn Migas, Rabbi Isaac ben Leon, and Rabbi Nehemiah, who was called Escafa, three Granada notables, favored Bulukkin, but Rabbi Samuel Ha―Levi favored Badis. On the day that King Habbus died, the Berber princes and their distinguished men rose in the morning to crown his son Bulukkin. Bulukkin, however, immediately went and kissed the hand of his elder brother Badis. Thus Badis was crowned in the year 4787 [1027] and the face of his enemies turned black like the bottom of a pot; and against their will they had to crown Badis. [Badis was really crowned in 1038 and died in 1073.] [Source: Jacob Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook, 315-1791, (New York: JPS, 1938), 297-300, later printed Atheneum, 1969, 1972, 1978, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“After this Bulukkin regretted that he had made his brother king and kept on getting the upper hand over his brother Badis, with the result that King Badis was unable to do a thing, big or small, without his brother's interference. But after this his brother Bulukkin became sick, and the King gave orders to the physician not to cure him. The physician obeyed, and Bulukkin died. Thus was the kingdom established in the hands of Badis. These three distinguished Jews of the city, whom we have mentioned, fled to the land of Seville [then hostile to Granada].

“Rabbi Samuel Ha―Levi was appointed Prince in the year 4787 [1027], and he conferred great benefits on Israel in Spain, in north-eastern and north―central Africa, in the land of Egypt, in Sicily, well as far as the Babylonian academy, and the Holy City, Jerusalem. All the students who lived in those lands benefited by his generosity, for he bought numerous copies of the Holy Scriptures, the Mishnah, and the Talmud-these, too, being holy writings. [Ibn Daud here refutes the Karaites who denied the authority of the Mishnah and the Talmud.]

French Jews in the 18th century

“To every one-in all the land of Spain and in all the lands that we have mentioned-who wanted to make the study of the Torah his profession, he would give of his money. He had scribes who used to copy Mishnahs and Talmuds, and he would give them as a gift to students, in the academies of Spain or in the lands we have mentioned, who were not able to buy them with their own means. [Printing was not yet invented. Manuscripts were very expensive.] Besides this, he furnished olive oil every year for the lamps of the synagogues in Jerusalem. He spread the knowledge of the Torah [Jewish learning] very widely and died an old man, at a ripe age, after having acquired the four crowns: the crown of the Torah, the crown of high station, the crown of Levitical descent, and what is more than all these, the crown of a good name merited by good deeds. He died in the year 4815 [1055] and his son, Rabbi Joseph Ha―Levi, the Prince, succeeded him. [It is more probable that Samuel died in 1056 or later when Joseph (b. 1035), succeeded him as vizier.]

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook, 315-1791" by Jacob Rader Marcus Amazon.com ;

“England's Jews: Finance, Violence, and the Crown in the Thirteenth Century” by John Tolan Amazon.com ;

“The Khazars: A Judeo-Turkish Empire on the Steppes, 7th–11th Centuries AD (Illustrated) by Mikhail Zhirohov Amazon.com ;

“The Invention of the Jewish People” by Shlomo Sand and Yael Lotan Amazon.com ;

“The Devil and the Jews: The Medieval Conception of the Jew and Its Relation to Modern Anti-Semitism” by Joshua Trachtenberg Amazon.com ;

“Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages” by David Nirenberg Amazon.com ;

“The Transformation of Israelite Religion to Rabbinic Judaism” by Juan Marcos Bejarano Gutierrez Amazon.com ;

“The Jews of Iberia: A Short History” by Juan Marcos Bejarano Gutierrez Amazon.com ;

“Foundations of Sephardic Spirituality: The Inner Life of Jews of the Ottoman Empire”

by Rabbi Marc D. Angel Amazon.com ;

“Guide for the Perplexed” by Moses Maimonides, Andrea Giordani, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

““The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal” by Yonatan Adler Amazon.com ;

“"Early Judaism: A Comprehensive Overview" by John J. Collins and Daniel C. Harlow Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com

Creation of Judaism

The evolution from Hebraism (a religion based only on the scriptures of the Old Testament) to Judaism (with rabbis and religion doctrine interpreted by these rabbis) was a slow transformation that began in the destruction of the Second Temple (A.D. 70) and the compilation of the “Mishnah” (Judaism’s first major canonical document following the Bible) in the A.D. second century. During this time Judaism absorbed new ideas and faced new problems, many resulting from war and dislocation.

The evolution from Hebraism (a religion based only on the scriptures of the Old Testament) to Judaism (with rabbis and religion doctrine interpreted by these rabbis) was a slow transformation that began in the destruction of the Second Temple (A.D. 70) and the compilation of the “Mishnah” (Judaism’s first major canonical document following the Bible) in the A.D. second century. During this time Judaism absorbed new ideas and faced new problems, many resulting from war and dislocation.

Alexandria was a center of Jewish intellectual life as well as Greek, Roman and Christian intellectual thought. Jewish scholars such as Philo of Alexandria were deeply influenced by Greek philosophy, which helped them find a vocabulary and ideas to address some of the more abstract concepts of their religion especially when it came to God. By contrast scholars that stayed close to their roots in Palestine stayed truer to the Bible and conceptualized God in more human and anthropomorphic terms. The evolution of these two methods of approaching Judaism led to articulation of the more mysterious aspects of Judaism and a codification of its laws. The creation of Judaism was the work of rabbis who reconstructed the religion of the Jews by interpreting the Torah in a world without a Temple based on oral traditions, families and synagogues. The record of these rabbis formed the basis for the Mishnah and the Talmud.

In the Middle Ages there were many Jewish sects. In some cases each had its own Talmud. In time the the Babylonian Talmud predominated over the others. These were later organized into codes of which the code of Maimonides (1135-1204) and Joseph Caro (1488-1575), known as “Shulchan Aruch”, became the most important.

Theological Developments in Medieval Judaism

Louis Jacobs wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: During the Middle Ages Judaism was confronted with the challenge of Greek philosophy in its Arabic garb. The Jews mainly affected were those of Spain and Islamic lands. The French and German Jews were more remote from the new trends, and their work is chiefly a continuation of the rabbinic modes of thinking. The impact of Greek thought demanded both a more systematic presentation of the truths of the faith and a fresh consideration of what these were in the light of the new ideas. A good deal of the conflict was in the realm of particularism. [Source: Louis Jacobs, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

There is definite hostility in much of Greek thought to the notion of truths capable of being perceived only by a special group. Truth is universal and for all men. There is a marked tendency in medieval Jewish thought to play down Jewish particularism. This is not to say that Judaism was held to be only relatively true, but that the doctrine of Israel's chosenness had become especially difficult to comprehend philosophically. The greatest thinker of this period, Maimonides, hardly touches on the question of the chosen people and, significantly enough, does not number the doctrine among his principles of the faith.

For most of the thinkers of this age a burning problem was the relationship between reason and revelation. What need is there for a special revelation of the truth if truth is universal and can be attained by man's unaided reason? In rabbinic times, wisdom is synonymous with Torah. The tendency in medieval thought is to give wisdom its head but to incorporate this, too, under the heading of Torah. Greek physics and metaphysics thus not only become legitimate fields of study for the Jew but part of the Torah (Maim. Yad, Yesodei ha-Torah, 2:5).

See Separate Article: DEVELOPMENT OF RABBINIC JUDAISM: A.D. FIRST TO FIFTH CENTURIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Early Jewish Thinkers and Theologians

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Other than certain books of the Bible, the first work by a Jewish author to appear under the name of an individual was that of the philosopher Philo (c. 20 B.C.–50 A.D.), who lived in Alexandria. Writing in Greek, he composed an exegesis of the Bible in which many passages were interpreted as allegorical elucidations of metaphysical truths. His concept that God created the world through Logos had a profound impact on the Christian dogma that identified Jesus with the Logos. The Christian church therefore preserved many of Philo's writings, which, other than a few brief passages cited in the Talmud, were forgotten by his fellow Jews after his death. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Sustained Jewish interest in philosophy was to be manifest only under the impact of Islamic thought, which was nurtured by Greek philosophy, and by and large Jewish philosophy was philosophy of religion. Writing for the most part in Arabic, Jewish philosophers used the philosopher's tools to address religious or theological questions. It is significant that medieval Jewish philosophy was inaugurated by a gaon (head) of one the leading rabbinical academies in Babylonia, the Egyptian-born Saadiah Gaon [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Saadia Gaon (882–942) is considered "the father of Jewish philosophy." He took up the defense of rabbinic Judaism against the Karaites. His “Book of Beliefs and Opinions,” written in Arabic and later translated into Hebrew, presented a rational analysis and proof of the basic theological concepts of Judaism. He propounded the unity of revelation and reason. The new element in his thought is its debt to Muslim theology. Saadia thus ushers in a line of medieval thinkers whose thought is born of a meeting with Muslim and Christian theologies, Neoplatonism, or Aristotelianism. [Source: J.M Oesterreicher, New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

There was a famous series of theological debates between priests and rabbis in the 13th and 14th century sponsored by the Catholic church. The rabbis were in a no-win situation. If they lost they lost; if they won they risked being lynched by a mob. A famous duel between a Jewish convert to Christianity named Pablo Christian and Nachmanides of Girona, the most famous Talmudic scholar of his generation, took place in Barcelona in 1283. Nachmanides performed so well he was charged with blasphemy and forced to leave the country.

Spanish Jewish Thinkers and Theologians

Maimonides Among the most important Jewish philosophers was Avicebron (Solomon Ibn Gabirol, c. 1026–50), who marked the shifting of the focal point of Jewish thought to Spain. According to him all things emanate from God as the first principle, not by necessity but through His loving will. Avicebron's depth may be shown by the climactic stanza of one of his poems: When all Thy face is dark, And Thy just angers rise, From Thee I turn to Thee And find love in Thine eyes. [Source: J.M Oesterreicher, New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Avicebron wrote a Neoplatonic defense of the biblical concept of creation that, translated from the Arabic into Latin as Fons vitae ("Fountain of Life"), deeply influenced Christian theology. Drawing on Islamic mysticism, Neoplatonic philosophy, and perhaps even esoteric Christian literature, Bahya ibn Pakuda (second half of the eleventh century), who also lived in Spain, wrote on ethical and spiritual life in Duties of the Heart, which first appeared in 1080 in Arabic. Through translations into Hebrew, the first of which had already appeared in the late twelfth century, and other languages, this guide is still widely studied within the Jewish community. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The first to treat Jewish ethics systematically was Avicebron's contemporary Bahya ibn Paquda (1050–1120). His Duties of the Heart became a guide to the inner life for untold numbers of Jews. He espoused asceticism, denounced giving into one’s desires and developed a kind of Jewish Sufism and brought it to a large audience. Abraham ibn Daud (c. 1110–c. 1180) was a Spanish philosopher whoo wrote in Arabic. In “The Exalted Faith” he systematically sought to harmonize the principles of Judaism with Aristotelian rationalist philosophy.

Judah Halevi

Judah Halevi (c.1080-1145) was a great rabbi-poet and Jewish thinker who approached Judaism from a different perspective and is also considered one of the greatest Jewish poets. He was born in Toledo, Spain, while it was under Islamic rule, but spent much of life in Palestine. In his work he stressed an intense, deeply personal love of God, fealty to the Jewish community and a desire for divine communion. Halevi was an outgoing physician and court poet. He wrote religious verse and secular poems and were liked by Jews, Christians and Muslims alike. Many of his poems dealt with spirituality, alienation and the longing for a homeland. Some of his poems, such as “Ode to Zion”, are still fixtures of Jewish religious services.

One Halevi poem goes:

“Lord Where shall I find thee?

High and hidden is they place;

And where shall I not fond thee?

The world is full of thy glory” .

Rather than defend Judaism, Halevi attempted to show its superiority over Christianity and Islam. Although he enjoyed the comforts of "the golden age of Spanish Jewry," he felt that the Jews were in exile and he dreamed of Zion. Jews, he held, bore the sufferings of the world; their restoration to the Holy Land would bring salvation to the entire earth. Yet he sang also: "Would I might behold His face within my heart!/Mine eyes would never ask to look beyond."

Judah Halevi (also spelled Yehudah Ha-Levi) was a prolific writer of both Arabic and Hebrew poetry. From 1120 to 1140, he wrote the famous five-chapter book known as The Kuzari.. It explored things like the difference between the God of Aristotle (a bloodless abstraction) and the God of Abraham (a living god experienced through personal revelation) and reconciled reason, history, love and religion.

Around 800 of Halevi’s works and poems can still be read. Kuzari (“The Book of the Kuzars”) was written in Arabic in the form of a dialogue between a Jewish scholar and the king of the Khazars, who was subsequently to convert to Judaism, The book explores the conflict between philosophy and revealed faith. Exposing what he believes to be the limitations of Aristotlean philosophy, he argues that only religious faith that affirms God's transcendence and the gift of revelation, namely, the Torah and its commandments, can bring a person close to God.

Maimonides

Moses Maimonides (1135-1204) is regarded as the greatest Torah scholar, the most important medieval Jewish philosopher and the most influential rationalist thinker of Judaism. He is the author of “The Guide to the Perplexed” and the Thirteen Articles of Faith and the source of many Talmudist and Rabbinic laws. Both Maimonides and the Muslim philosopher and scientist Averroes were born in the Spanish city of Cordova and it is said that they became good friends.

Maimonides was a physicians and polymath. He advocated rationalism and was an admirer of Greek philosophy. He was both a clever Aristotlean thinker and believer that all fundamental truths can be found in the Torah. His ideas however were quite controversial and split Judaism into two camps.

The Thirteen Articles of Faith of Maimonides are regarded as the basic dogma of Judaism. They are: 1) The existence of God, the Creator of All Things; 2) His absolute unity; 3) His incorporeality; 4) His eternity; 5) The obligation to serve and worship him alone; 6) The existence of prophecy; 7) The superiority of the Prophecy of Moses above all others; 8) The “Torah” is God’s revelation to Moses; 9) “The Torah” is immutable; 10) God’s omniscience and foreknowledge; 11) Rewards and punishments according to one’s deeds; 12) The coming of the Messiah; 13) The resurrection of the dead.

Law Codes, and Biblical Exegesis

Maimonides' teaching

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The great codes of Jewish law were compiled in this period, partly in response to the new demand for great systemization, partly because the laws were scattered through the voluminous talmudic literature and required to be brought together, so that the posekim could easily find the sources of their decisions. A further aim was to render decisions in cases of doubt.[Source: Louis Jacobs,Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

In addition to the incorporation of secular learning into Torah, the scope of Torah studies proper was widened considerably. The Karaites were responsible for a new flowering of biblical scholarship. The Kabbalah was born, its devotees engaging in theosophical reflection on the biblical texts. According to the Kabbalah every detail of the precepts mirrored the supernal mysteries, and the performance of the precepts consequently had the power of influencing the higher worlds. In the writings of the later kabbalists, Judaism becomes a mystery religion, its magical powers known only to the mystical adepts.

Influence of Mysticism, Gnosticism and Greek Thought on Judaism

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Under the impact of Greek thought the emphasis in medieval Jewish thinking among the philosophers is on the impersonal aspects of the Deity. Not only is anthropomorphism rejected but the whole question of the divine attributes — of what can and cannot be said about God — receives the closest scrutiny. Ba ya ibn Paquda (Duties of the Heart, Sha'ar ha-Yi ud, 10) and Maimonides (Guide, 1:31–60) allow only negative attributes to be used of the Deity; to say that God is wise is to say no more than that He is not ignorant. It is not to say anything about the reality of the divine nature in itself which must always remain utterly incomprehensible. [Source: Louis Jacobs,Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

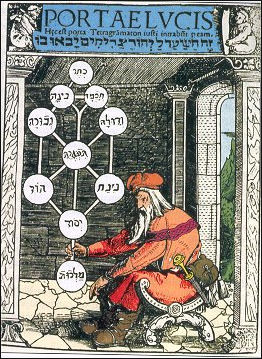

In reaction to the philosophers' depersonalization of the Deity, the kabbalists, evidently under Gnostic influence, developed the doctrine of the Sefirot, the ten divine emanations by which the world is governed, though among the kabbalists, too, in the doctrine of Ein Sof ("the Limitless"), God as He is in Himself — the Neoplatonic idea of deus absconditus — is preserved. Indeed, from one point of view, the Kabbalah is more radical than the philosophers in that it negates all language from Ein Sof. The utterly impersonal ground is not mentioned in the Bible. Of it nothing can be said at all. No name can be given it except the negative one of "Nothing" (because of it, nothing can be postulated). By thus affirming both the impersonal ground and the dynamic life of the Sefirot, the kabbalists endeavor to satisfy the philosophical mind while catering to the popular need for the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Kabbalah

Kabbalah Tree of Life

from Medieval times The Kabbalah is the name given to Jewish mystical knowledge passed down orally from generation to generation and hinted at in the Talmud. It is concerned with finding hidden meaning in the Scriptures, reaching elevated planes and ecstatic states, delving into magic, and speculating on the coming of the Messiah. Kabbalah has been compared to Sufism, Islamic mysticism. The word Kabbalah roughly means “esoteric tradition” and more precisely “what is receives,” a reference to Moses receiving the laws of God at Mt. Sinai, and a word widely used on modern Israel to describe the reception desk at hotels, among other things.

Despite claims that Kabbalah is a form of mystical teaching practiced by Moses it in fact has it origins in medieval Europe. In 13th century Spain and southern France, Jewish scholars claimed they possessed secret scriptural knowledge that had originated with Moses and had been passed down orally over the centuries. These scholars and exegetes, later known as kabbalists, were focused primarily on two sections of the Torah that were forbidden by the Talmud to be discussed publically. The first is the description of Creation in Genesis and the second is a description in the Book of Ezekial of Ezekial’s vison of a cosmic chariot.

“The World of Emanations” , a complex organization consisting of ten hierarchically-arranged “sefirot” (variously described as potencies, emanations, arteries. potentialities or foci), was described in the 12th century (See Below). The Zohar, Kabbalah’s main text, was written in the 13th century.

Kabbalah emerged at a time when Judaism was dominated by rabbis who set rigid, detailed laws that all Jews were expected to follow unquestioningly. Judaism at that time was based in moral rationalism and included a code of ethics. It emphasized the primacy of charity and discredited esoteric beliefs and pursuing deep issues such as the meaning of God. Kabbalists sought not only to define and characterize God but also to tap into his spiritual and cosmological power, a pursuit regarded by purists as heretical.

Kabbalists first scrutinized non-Kabbalist Jewish texts and came up with elaborate and complex models of the cosmos based on interpretations of these texts. They described the kingdom of heaven and how humans could transcend their own being and “face God in his glory.”

See Separate Article: KABBALAH, MYSTICAL JUDAISM AND THEIR HISTORY africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024