HISTORY OF CHRISTMAS

According to the BBC: “Christmas has always been a strange combination of Christian, Pagan and folk traditions. As far back as 389 AD, St Gregory Nazianzen (one of the Four Fathers of the Greek Church) warned against 'feasting in excess, dancing and crowning the doors'. The Church was already finding it hard to bury the Pagan remnants of the midwinter festival. [Source: June 22, 2009, BBC |::|]

“During the medieval period (c.400AD - c.1400AD) Christmas was a time for feasting and merrymaking. It was a predominantly secular festival but contained some religious elements. Medieval Christmas lasted 12 days from Christmas Eve on 24th December, until the Epiphany (Twelfth Night) on 6th January. Epiphany comes from a Greek word that means 'to show', meaning the time when Jesus was revealed to the world. Even up until the 1800s the Epiphany was at least as big a celebration as Christmas day. |::|

“Many Pagan traditions had been brought to Britain by the invading Roman soldiers. These included covering houses in greenery and bawdy partying that had its roots in the unruly festival of Saturnalia. The Church attempted to curb Pagan practices and popular customs were given Christian meaning. Carols that had started as Pagan songs for celebrations such as midsummer and harvest were taken up by the Church. By the late medieval period the singing of Christmas carols had become a tradition. |::|

“The Church also injected Christian meaning into the use of holly, making it a symbol for Jesus' crown of thorns. According to one legend, the holly's branches were woven into a painful crown and placed on Christ's head by Roman soldiers who mocked him, chanting: "Hail King of the Jews." Holly berries used to be white but Christ's blood left them with a permanent crimson stain. |::|

“Another legend is about a little orphan boy who was living with shepherds when the angels came to announce Jesus' birth. The child wove a crown of holly for the newborn baby's head. But when he presented it, he became ashamed of his gift and started to cry. Miraculously the baby Jesus reached out and touched the crown. It began to sparkle and the orphan's tears turned into beautiful scarlet berries. |::|

See Separate Articles CHRISTMAS AND HOLIDAYS IN THE CHRISTMAS SEASON factsanddetails.com and ST. NICHOLAS AND HIS TRANSFORMATION INTO SANTA CLAUS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ;Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Internet Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christian Denominations: Holy See w2.vatican.va ; Catholic Online catholic.org ; Catholic Encyclopedia newadvent.org ; World Council of Churches, main world body for mainline Protestant churches oikoumene.org BBC on Baptists bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; BBC on Methodists bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; ; Orthodox Church in America oca.org/saints/lives ; Online Orthodox Catechism published by the Russian Orthodox Church orthodoxeurope.org

Midwinter Celebrations

According to the BBC: “Christmas comes just after the middle of winter. The sun is strengthening and the days are beginning to grow longer. For people throughout history this has been a time of feasting and celebration. Ancient people were hunters and spent most of their time outdoors. The seasons and weather played a very important part in their lives and because of this they had a great reverence for, and even worshipped, the sun. The Norsemen of Northern Europe saw the sun as a wheel that changed the seasons. It was from the word for this wheel, houl, that the word yule (another name for Christmas) is thought to have come. At Winter Solstice the Norsemen lit bonfires, told stories and drank sweet ale.

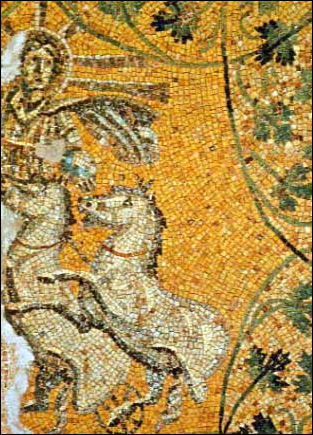

Christ as the Sun, 3rd century “The Romans also held a festival to mark the Winter Solstice. Saturnalia (from the God Saturn) ran for seven days from 17th December. It was a time when the ordinary rules were turned upside down. Men dressed as women and masters dressed as servants. The festival also involved processions, decorating houses with greenery, lighting candles and giving presents. [Source: June 22, 2009, BBC |::|]

“Holly is one of the symbols most associated with Christmas. Its religious significance pre-dates Christianity. It was previously associated with the Sun God and was important in Pagan customs. Some ancient religions used holly for protection. They decorated doors and windows with it in the belief it would ward off evil spirits. |::|

“Before Christianity came to the British Isles the Winter Solstice was held on the shortest day of the year (21st December). The Druids (Celtic priests) would cut the mistletoe that grew on the oak tree and give it as a blessing. Oaks were seen as sacred and the winter fruit of the mistletoe was a symbol of life in the dark winter months. |::|

“Judaism was the main religion of Israel at the time of Jesus' birth. The Jewish midwinter festival of Hanukkah marks an important part of Jewish history. It is eight days long and on each day a candle is lit. It is a time of remembrance, celebration of light, a time to give gifts and have fun. |::|

Winter Solstice

In the Northern hemisphere, Christmas is a few days away from the Winter Solstice, shortest day and longest night of the year, falling on December 21 or December 22. According to History.com: Many ancient people believed that the sun was a god and that winter came every year because the sun god had become sick and weak. They celebrated the solstice because it meant that at last the sun god would begin to get well. Evergreen boughs reminded them of all the green plants that would grow again when the sun god was strong and summer would return. [Source: History.com]

The ancient Egyptians worshipped a god called Ra, who had the head of a hawk and wore the sun as a blazing disk in his crown. At the solstice, when Ra began to recover from the illness, the Egyptians filled their homes with green palm rushes which symbolized for them the triumph of life over death.

Early Romans marked the solstice with a feast called the Saturnalia in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture. The Romans knew that the solstice meant that soon farms and orchards would be green and fruitful. To mark the occasion, they decorated their homes and temples with evergreen boughs. In Northern Europe the mysterious Druids, the priests of the ancient Celts, also decorated their temples with evergreen boughs as a symbol of everlasting life. The fierce Vikings in Scandinavia thought that evergreens were the special plant of the sun god, Balder.

Golden Bough Theory of Christmas’s Origin

Birth of Christ in a Hungarian manuscript

Valerie Strauss wrote in the Washington Post, “One of the prevalent theories on why Christmas is December 25 was spelled out in “The Golden Bough,” a highly influential 19th century comparative study of religion and mythology written by the anthropologist Sir James George Frazer and originally published in 1890. Frazer approached the topic of religion from a cultural — not theological — perspective, and he linked the dating of Christmas to earlier pagan rituals. [Source: Valerie Strauss, Washington Post, December 24, 2014]

On the origins of Christmas, the 1922 edition of the “The Golden Bough” published on Bartleby.com reads: “An instructive relic of the long struggle is preserved in our festival of Christmas, which the Church seems to have borrowed directly from its heathen rival. In the Julian calendar the twenty-fifth of December was reckoned the winter solstice, and it was regarded as the Nativity of the Sun, because the day begins to lengthen and the power of the sun to increase from that turning-point of the year. The ritual of the nativity, as it appears to have been celebrated in Syria and Egypt, was remarkable. The celebrants retired into certain inner shrines, from which at midnight they issued with a loud cry, “The Virgin has brought forth! The light is waxing!” The Egyptians even represented the new-born sun by the image of an infant which on his birthday, the winter solstice, they brought forth and exhibited to his worshippers.

No doubt the Virgin who thus conceived and bore a son on the twenty-fifth of December was the great Oriental goddess whom the Semites called the Heavenly Virgin or simply the Heavenly Goddess; in Semitic lands she was a form of Astarte. Now Mithra was regularly identified by his worshippers with the Sun, the Unconquered Sun, as they called him; hence his nativity also fell on the twenty-fifth of December. The Gospels say nothing as to the day of Christ’s birth, and accordingly the early Church did not celebrate it. In time, however, the Christians of Egypt came to regard the sixth of January as the date of the Nativity, and the custom of commemorating the birth of the Saviour on that day gradually spread until by the fourth century it was universally established in the East. But at the end of the third or the beginning of the fourth century the Western Church, which had never recognised the sixth of January as the day of the Nativity, adopted the twenty-fifth of December as the true date, and in time its decision was accepted also by the Eastern Church. At Antioch the change was not introduced till about the year 375 A.D. [Source: “The Golden Bough” by Sir James George Frazer, 1890, 1922 edition, Bartleby.com]

“What considerations led the ecclesiastical authorities to institute the festival of Christmas? The motives for the innovation are stated with great frankness by a Syrian writer, himself a Christian. “The reason,” he tells us, “why the fathers transferred the celebration of the sixth of January to the twenty-fifth of December was this. It was a custom of the heathen to celebrate on the same twenty-fifth of December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and festivities the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnised on that day and the festival of the Epiphany on the sixth of January. Accordingly, along with this custom, the practice has prevailed of kindling fires till the sixth.” The heathen origin of Christmas is plainly hinted at, if not tacitly admitted, by Augustine when he exhorts his Christian brethren not to celebrate that solemn day like the heathen on account of the sun, but on account of him who made the sun. In like manner Leo the Great rebuked the pestilent belief that Christmas was solemnised because of the birth of the new sun, as it was called, and not because of the nativity of Christ.”

Biblical Archaeology Society’s Theory of Christmas’s Origin

Three wise men relief from Gotland, Sweden

The Biblical Archaeology Society’s Web site says: “Despite its popularity today, this theory of Christmas’s origins has its problems. It is not found in any ancient Christian writings, for one thing. Christian authors of the time do note a connection between the solstice and Jesus’ birth: The church father Ambrose (c. 339–397), for example, described Christ as the true sun, who outshone the fallen gods of the old order. But early Christian writers never hint at any recent calendrical engineering; they clearly don’t think the date was chosen by the church. Rather they see the coincidence as a providential sign, as natural proof that God had selected Jesus over the false pagan gods. [Source: Valerie Strauss, Washington Post, December 24, 2014]

Furthermore, it says, the first mentions of a date for Christmas, around 200 A.D., were made at a time when “Christians were not borrowing heavily from pagan traditions of such an obvious character.” It was in the 12th century, it says, that the first link between the date of Jesus’s birth and pagan feasts was made.

It says in part: “Clearly there was great uncertainty, but also a considerable amount of interest, in dating Jesus’ birth in the late second century. By the fourth century, however, we find references to two dates that were widely recognized — and now also celebrated — as Jesus’ birthday: December 25 in the western Roman Empire and January 6 in the East (especially in Egypt and Asia Minor). The modern Armenian church continues to celebrate Christmas on January 6; for most Christians, however, December 25 would prevail, while January 6 eventually came to be known as the Feast of the Epiphany, commemorating the arrival of the magi in Bethlehem. The period between became the holiday season later known as the 12 days of Christmas.”

Is Christmas Really Based on Roman and Pagan Festivals

Candida Moss wrote in The Daily Beast: If celebration of Christ’s birth is based on a pre-existing festival, then there are at three prime candidates: the birthday of the ancient Sun God (Sol Invictus), the Roman festival of Saturnalia which takes place around this time, and the widely celebrated Winter Solstice. [Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast December 25, 2022]

Perhaps the most superficially similar festival is the birthday of Sol Invictus (the "Unconquered Sun" who was also known as Helios). Sol Invictus was one of several "sun gods" who were worshipped in the Roman Empire and according to an ancient calendar known as the Chronograph of 354 A.D. his birthday was celebrated on 25th of December. A Sun God and the Son of God shared a birthday? What are the chances?

From the medieval period onwards, people have speculated that December 25th was selected because of Sol Invictus. The Syrian Bishop Jacob bar Salibi (d. 1171 A.D.), who celebrated Jesus’s birth on Epiphany, wrote “The reasons for which the Fathers transferred the said solemnity [the Nativity] from the sixth of January to the 25th of December is…[that] it was the custom of the pagans to celebrate on this same day … the feast of the birth of the sun.” As an Eastern Christian who celebrated the Nativity and Epiphany in January, Jacob had a clear motive for undermining the December date, but was he right?

It's unlikely, primarily because the chronology is a bit off. The popular religion Youtuber and scholar Dr. Andrew Henry explains that Sol Invictus only became popular during the later third century A.D. It was only in 274, after the emperor Aurelian credited Sol Invictus with assisting him in battle, that resources were dedicated to god’s cult. Aurelian dedicated a new Temple to Sol Invictus and founded what Henry calls the “Sol Olympics.” But before this point Sol Invictus was a bit-player in the Roman pantheon. Because Christians had begun observing Christmas in December in the early third century, the two celebrations seem to be independent. It’s a coincidence, but one that probably worked to the advantage of early Christians.

Then there’s the Winter Solstice. This year, you probably noticed, the shortest day of the year was December 21, but Roman authors like Pliny the Elder placed it on December 25. The event was cross-cultural: whether you were at Stonehenge or the Pantheon, anyone interested in time, the seasons, and the cosmos saw the solstice as a special event. As Dr. Eric Vanden Eykel, author of the newly released book The Magi, told me, the Winter Solstice “was broadly understood in the Roman world to have cosmological significance.” It was observed by a variety of ancient groups including the Druids, who (according to Pliny) marked the day by sacrificing bulls and gathering mistletoe. Some of that feels familiar.

Christmas and Saturnalia.

Roman Saturnalia

Christmas has been linked with the Roman festival of Saturnalia. Saturnalia was the winter celebration to the god Saturn. Saturn was identified with the Greek god Kronos, and he was sacrificed to according to Greek ritual during this festival. The Temple of Saturn, the oldest temple recorded by the pontifices, was dedicated on the Saturnalia, and the woolen bonds which fettered the feet of the ivory cult statue within were loosened on that day to symbolize the liberation of the god. [Source: persweb.wabash.edu ~~]

The Saturnalia festival lasted seven days and was celebrated for during week leading up to the winter solstice. Historical sources indicate that it was the most wild and popular festive period in the year. Saturnalia was marked by gift giving. This is one reason why people believe that Saturnalia was absorbed into Christmas. The festival also had a day where the slave and master would trade places. The masters would serve their slaves and the slaves would go out into the streets and gamble with dice, a pastime that was illegal during the rest of the year. On the day of the festival, a sacrifice took place at the Temple of Saturn which was followed by a public banquet. As they left the banquet, the citizens are reputed to have shouted "IO, Saturnalia!"” ~

Candida Moss wrote in The Daily Beast: Just like Christmas today, Saturnalia was part religious festival and part opportunity to skip work and drink too much. According to the agricultural writer Columella, it was officially celebrated on December 17, but by the time of Cicero (first century B.C.) it lasted for three or even seven days. It was a raucous affair with people greeting one another with the traditional “Io, Saturnalia.” Catullus called it “the best of days” complete with food, drink, games, gambling, and gift giving. Homes were decorated with evergreen wreaths and berries and, on the final day (December 23), candles and small terracotta figurines (sigallaria) were given as gifts, particularly to children. The noise of the celebrations got so bad that the Roman statesman and writer Pliny had to construct a special writing chamber to block out the din.[Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast December 25, 2022]

A religious festival that involves candles, gift-giving, evergreen decor, songs, and food, it all sounds a touch familiar but was Saturnalia the source of Christian revelry? There’s no shortage of memes and videos out there but, once again, the timeline is a bit off. Saturnalia finished by December 23 and while we might be tempted to say “well, close enough” the precise date was enormously important because it said something about the importance of Jesus.

Influence of Pagan Festivals on Christmas

Although bishops could get snippy about Christians who participated in pagan religious activities, Christians leaders don’t seem to have been that concerned about competing with Sol Invictus, the Solstice, or Saturnalia. Dr. Dan McClellan, a debunker of myths about the Bible on Instagram and TikTok and scholar of religious studies and theology said that while the actual date of Christmas probably wasn’t determined by the Solstice or Saturnalia, the celebration of pagan festivals probably did affect how Christians marked their holidays. There may have been “some incentive, whether conscious or otherwise, [for Christians] to commit to that date.” In his video, Henry notes that if Christmas is related to these other festivals, it was “not in the sense of stealing a Roman holiday.”

When I asked McClellan why it is that people today think Christians stole the winter festival McClellan told me that it’s obvious that many of the traditions associated with Christmas (think mistletoe) don’t have clear ties to Jesus or Christianity. The mythology of Christians "stealing Christmas," said McClellan might be a form of resistance that helps people makes sense of things: “it offers a way to ‘punch up’ against the oppressive and imperialist institutions of Christianity by exposing them as appropriators of the traditions of marginalized groups. I imagine there are also folks who enjoy feeling like they have insider knowledge that bucks the conventional wisdom, even if in this case it's more the ‘conventional wisdom’ than the insider knowledge.”

The close association of pagan festivals with Christmas; though, allowed Christians to amplify certain elements of the Jesus story and capitalize on the celebration’s similarity to more familiar holidays that elicited warm and fuzzy feelings in people. Some late antique Christians like Gregory of Nyssa and Paulinus of Nola explicitly linked the death of Jesus to the Winter Solstice because of the symbolism of darkness and light. The idea of Jesus as a light breaking into the world on the darkest day of the year was too good to pass up.

Saturnalia, too, resonated with the Gospel portrayal of Jesus as a messiah who came to save the downtrodden. In essence, Saturnalia was a brief period of role reversal when lower status people did not work, and enslaved people were permitted to dine with their enslavers. Adults would serve children and the cap of freedom (the pilleum) could be worn by anyone. The equality was only temporary, of course, but it resonated with the Christian message of future salvation for the marginalized. Christian scripture regularly looks forward to Judgment Day, when the poor, hungry, meek, and persecuted will see God, eat their fill, and inherit the Kingdom of God. If you squint a little, Saturnalia was a debauched X-rated pagan version of that; that principle of role reversal could be exploited in narrations of the birth of the Christ child.

History of Nativity Scenes

St. Francis of Assisi is credited with staging the first nativity scene in 1223. One account of Francis’ nativity scene comes from “The Life of St. Francis of Assisi” by St. Bonaventure, a Franciscan monk who was born five years before Francis’ death. According to Bonaventure, St. Francis received permission from Pope Honorious III to set up a manger with hay and two live animals—an ox and an ass—in a cave in the Italian village of Grecio. He then invited the villagers to come gaze upon the scene while he preached about “the babe of Bethlehem.” (Francis was supposedly so overcome by emotion that he couldn’t say “Jesus.”) Bonaventure also claims that the hay used by Francis miraculously acquired the power to cure local cattle diseases and pestilences. [Source: Rachel Nuwer, smithsonian.com, December 14, 2012]

L.V. Anderson wrote in Slate: While this part of Bonaventure's story is dubious, it's clear that nativity scenes had enormous popular appeal. Francis' display came in the middle of a period when mystery or miracle plays were a popular form of entertainment and education for European laypeople. These plays, originally performed in churches and later performed in town squares, re-enacted Bible stories in vernacular languages. Since church services at the time were performed only in Latin, which virtually no one understood, miracle plays were the only way for laypeople to learn scripture. Francis' nativity scene used the same method of visual display to help locals understand and emotionally engage with Christianity. [Source: L.V. Anderson, Slate.com]

“Within a couple of centuries of Francis' inaugural display, nativity scenes had spread throughout Europe. It's unclear from Bonaventure's account whether Francis used people or figures to stand in for Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, or if the spectators just used their imagination, but later nativity scenes included both tableaux vivants and dioramas, and the cast of characters gradually expanded to include not only the happy couple and the infant, but sometimes entire villages. The familiar cast of characters we see today—namely the three wise men and the shepherds—aren't biblically accurate. Of the four gospels in the New Testament, only Matthew and Luke describe Jesus’ birth, the former focusing on the story of the wise men’s trek to see the infant king, the latter recounting the shepherds’ visit to the manger where Jesus was born. Nowhere in the Bible do the shepherds and wise men appear together, and nowhere in the Bible are donkeys, oxen, cattle, or other domesticated animals mentioned in conjunction with Jesus’ birth. But early nativity scenes took their cues more from religious art than from scripture.

German nativity scene

“After the reformation, crèches became more associated with southern Europe (where Catholicism was still prevalent), while Christmas trees were the northern European decoration of choice (since Protestantism—and evergreens—thrived there). As nativity scenes spread, different regions began to take on different artistic features and characters. For example, the santon figurines manufactured in Provence in France are made of terra cotta and include a wide range of villagers. In the Catalonia region of Spain, a figure known as the caganer—a young boy in the act of defecating—shows up in most nativity scenes. In 20th- and 21st-century America, nativity figurines became associated with kitsch rather than piety, with nonreligious figures like snowmen and rubber ducks sometimes occupying the main roles.

“What about those nativity plays that children often perform at Christmastime? They are an obvious outgrowth of the miracle plays of the Middle Ages, but the reason children (rather than adults) perform in them isn’t clear. However, it’s possible the tradition stems from the Victorian Era, when Christmas was recast in America and England as a child-friendly, family-centered holiday, instead of the rowdy celebration it had been in years past.”

St. Francis Honors Christ with the First Nativity Scene

Thomas of Celano wrote: “His highest intention, greatest desire, and supreme purpose was to observe the holy gospel in and through all things. He wanted to follow the doctrine and walk in the footsteps of our Lord Jesus Christ, and to do so perfectly, with all vigilance, all zeal, complete desire of the mind, complete fervor of the heart. He remembered Christ's words through constant meditation and recalled his actions through wise consideration. The humility of the incarnation and the love of the passion so occupied his memory that he scarcely wished to think of anything else. Hence what he did in the third year before the day of his glorious death, in the town called Greccio, on the birthday of our Lord Jesus Christ, should be reverently remembered. [Source: Translation by David Burr olivi@mail.vt.edu, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“There was in that place a certain man named John, of good reputation and even better life, w ham the blessed Francis particularly loved. Noble and honorable in his own land, he had trodden on nobility of the flesh and pursued that of the mind. Around fifteen days before the birthday of Christ Francis sent for this man, as he often did, and said to him, "If you wish to celebrate the approaching feast of the Lord at Greccio, hurry and do w hat I tell you. I w ant to do something that w ill recall the memory of that child who was born in Bethlehem, to see with bodily eyes the inconveniences of his infancy, how he lay in the manger, and how the ox and ass stood by." Upon hearing this, the good and faithful man hurried to prepare all that the holy man had request ed.

“The day of joy drew near, the time of exult at ion approached. The brothers were called from their various places. With glad hearts, the men and w omen of that place prepared, according to their means, candles and torches to light up that night which has illuminated all the days and years with its glittering star. Finally the holy man of God arrived and, finding everything prepared, saw it and rejoiced.

Saint Francis and the Nativity

“The manger is ready, hay is brought, the ox and ass are led in. Simplicity is honored there, poverty is exalted, humility is commended and a new Bethlehem, as it were, is made from Greccio. Night is illuminated like the day, delighting men and beasts. The people come and joyfully celebrate the new mystery. The forest resounds with voices and the rocks respond to their rejoicing. The brothers sing, discharging their debt of praise to the Lord, and the whole night echoes with jubilation. The holy man of God stands before the m anger 12 full of sighs, consumed by devotion and filled with a marvelous joy. The solemnities of the mass are performed over the manger and the priest experiences a new consolation.

“The holy man of God wears a deacon's vestments, for he was indeed a deacon, and he sings the holy gospel with a sonorous voice. And his voice, a sweet voice, a vehement voice, a clear voice, a sonorous voice, invites all to the highest rewards. Then he preaches mellifluously to the people standing about, telling them about the birth of the poor king and the little city of Bethlehem. Often, too, when he wished to mention Jesus Christ, burning with love he called him "the child of Bethlehem," and speaking the word "Bethlehem" or "Jesus," he licked his lips with his tongue, seeming to taste the sweetness of these words.

“The gifts of the Almighty are multiplied here and a marvelous vision is seen by a certain virtuous man. For he saw a little child lying lifeless in the manger, and he saw the holy man of God approach and arouse the child as if from a deep sleep. Nor was this an unfitting vision, for in the hearts of many the child Jesus really had been forgotten, but now, by his grace and through his servant Francis, he had been brought back to life and impressed here by loving recollect ion. Finally the celebration ended and each returned joyfully home.

“The hay placed in the manger was kept so that the Lord, multiplying his holy mercy, might bring health to the beasts of burden and other animals. And indeed it happened that many animals throughout the surrounding area were cured of their illnesses by eating this hay. Moreover, w omen undergoing a long and difficult labor gave birth safely when some of this hay was placed upon them. And a large number of people, male and female alike, with various illnesses, all received the health they desired there. At last a temple of the Lord was consecrated w here the manger stood, and over the manger an altar was constructed and a church dedicated in honor of the blessed father Francis, so that, w here animals once had eaten hay, henceforth men could gain health in soul and body by eating the flesh of the Lamb without spot or blemish, Jesus Christ our Lord, who through great and indescribable love gave him self to us, living and reigning with the Father and Holy Spirit, God eternally glorious forever and ever, Amen. Alleluia! Alleluia!”

Ban on Christmas

Christman, banned in Boston

According to the BBC: “From the middle of the 17th century until the early 18th century the Christian Puritans suppressed Christmas celebrations in Europe and America. The Puritan movement began during the reign of Queen Elizabeth in England (1558-1603). They believed in strict moral codes, plenty of prayer and close following of New Testament scripture. [Source: June 22, 2009, BBC |::|]

“As the date of Christ's birth is not in the Gospels the Puritans thought that Christmas was too strongly linked to the Pagan Roman festival and were opposed to all celebration of it, particularly the lively, boozy celebrations inherited from Saturnalia. In 1644 all Christmas activities were banned in England. This included decorating houses with evergreens and eating mince pies. |::|

Christmas in the 19th Century

Americans only really began to celebrate Christmas widely in the second half of the nineteenth century. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The Puritans who came to the New World to escape religious intolerance in Europe didn’t celebrate Christmas at all. It was outlawed in New England from 1659-81. Why? They saw it as a Papist extravagance. As far as they were concerned it was a fourth-century innovation adapted in part from the pagan festival of Saturnalia. To this day there are homegrown American Christians that frown upon the celebration of Christmas because it’s not in the Bible. For them, as for the Puritans, Christmas is a gaudy distortion of the original message of Jesus. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 13, 2013]

According to the BBC: “After a lull in Christmas celebrations the festival returned with a bang in the Victorian Era (1837-1901). The Victorian Christmas was based on nostalgia for Christmases past. Dickens' A Christmas Carol (1843) inspired ideals of what Christmas should be, capturing the imagination of the British and American middle classes. This group had money to spend and made Christmas a special time for the family. |::|

“The Victorians gave us the kind of Christmas we know today, reviving the tradition of carol singing, borrowing the practice of card giving from St. Valentine's day and popularising the Christmas tree. Although the Victorians attempted to revive the Christmas of medieval Britain, many of the new traditions were Anglo-American inventions. From the 1950s, carol singing was revived by ministers, particularly in America, who incorporated them into Christmas celebrations in the Church. Christmas cards were first sent by the British but the Americans, many of whom were on the move and away from their families, picked up the practice because of a cheap postal service and because it was a good way of keeping in contact with people at home. |::|

“Christmas trees were a German tradition, brought to Britain and popularised by the royal family. Prince Albert first introduced the Christmas tree into the royal household in Britain in 1834. He was given a tree as a gift by the Queen of Norway which was displayed in Trafalgar Square. |::|

Myths about Christmas

Soviet poster from 1931

Christmas is the most important Christian holiday. James Martin wrote in the Washington Post, “For all the cards sent and trees decorated — to say nothing of all the Nativity scenes displayed — Christmas is not the most important date on the Christian calendar. Easter, the day on which Christians believe Christ rose from the dead, has more religious significance than does Dec. 25. Christ’s resurrection means not just that one man conquered death, nor was it simply proof of Jesus’s divinity to his followers; it holds out the promise of eternal life for all who believe in him. If Christmas is the season opener, Easter is the Super Bowl. The two holidays’ relative importance is even reflected in the church’s liturgical calendar. The Christmas season lasts 12 days, as all carolers know, ending with Epiphany, a feast day in early January commemorating the Wise Men’s visit to the infant Jesus. The Easter season, on the other hand, lasts 50 days. On Sundays during Eastertide, Christians hear dramatic stories of the post-resurrection appearances of Christ to his astonished followers. The overriding importance of Easter is simple: Anyone can be born, but not everyone can rise from the dead. [Source: James Martin, Washington Post, December 16, 2011. Martin is a Jesuit priest and author of "Seven Last Words."]

The secularization of Christmas is a recent phenomenon. “Worries about diluting Christmas’s meaning go much further back than recent memory. Gift-giving, for example, was seen as problematic as early as the Middle Ages, when the church frowned on the practice for its supposed pagan origins. More recently, some religious leaders in the 1950s fretted about the use of the term “Xmas” (which, depending on whom you believe, either substitutes a tacky “X” for Christ or uses the Greek letter chi, an ancient abbreviation for the word). The first few Christmas stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service in the early 1960s featured not the familiar Madonna and Child, but a bland wreath, an anodyne Christmas tree and sprigs of greenery.

And some of the most beloved “Christmas” TV shows from the 1960s — “How the Grinch Stole Christmas” and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” — have little to do with the birth of Christ and are more about vague holiday celebrations and, mostly, gifts. Linus’s famous recitation from Luke’s Gospel in “A Charlie Brown Christmas” is the exception in pop culture, not the rule. The overt religiosity of that scene, which flowed from the faith of Charles Schulz, drew criticism even at its first airing in 1965, as David Michaelis detailed in his 2008 biography of the cartoonist, “Schulz and Peanuts.”

Midnight Mass is at midnight. “One of the hoariest Catholic jokes — “What time is midnight Mass?” — is no longer so funny. Midnight Mass, traditionally the first celebration of the Christmas liturgy, is also when Saint Luke’s account of the birth of Jesus is read aloud. Recently, however, many churches have moved up their celebrations — first to 10 p.m., then to 8 p.m., and now as early as 4 p.m. Why? For one thing, churches are packed on Christmas Day. Second, the elderly and families with children may find it easier to attend services on the 24th, so as not to conflict with the following day’s festivities. As a result, some parishes are cutting back on Masses on Christmas Day. One parent recently told me: “We like to get Mass out of the way so that we can focus on the gifts.” (So, by moving Masses further from Dec. 25, churches may be contributing to the secularization of Christmas.) This trend prompted a pastor in New Jersey to send a missive this year noting that Christmas Eve Masses would be at 4 p.m., 6 p.m. and midnight — “as in the real midnight.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Encyclopedia.com, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024