Home | Category: Ice Age Animals / Ice Age Animals

WOOLLY MAMMOTHS

Woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) lived from 600,000 to 3,900 years ago and for a while lived at the same time as American mastodons (who lived from 3.75 million to 11,500 years ago) and African elephants and Asian elephants (who first appeared about 4 million years ago). Woolly mammoths were like elephants adapted for cold weather. They had thick skin and a heavy Woolly coat. Reaching a height of 14 feet at the shoulder and possessing upward curving tusks, considerably larger than those of an elephant, they lived in North America and Eurasia.

Scientists have a good idea what woolly mammoths looked like based on the discovery of frozen woolly mammoth carcasses in Alaska and Siberia as well as bones and other remains found over a large area. In 2013, scientists found a baby woolly mammoth entombed in ice in Russia. Many woolly mammoth teeth and tusks have been discovered, some with human engravings on them. well. Early humans killed Woolly Mammoths for a number of reasons. They ate the meat, but they also made art, homes and tools out of the bones and tusks. [Source: extinct-animals-facts.com]

In 1796, French Zoologist Baron Georges Cuvier was the first to identify the Woolly Mammoth as an extinct species of elephant.Mammoths were first described by German scientist Johann Friedrich Blumenback in 1799. He gave the name Elephas primigenius to elephant-like bones that had been found in Europe. Both Blumenback and Cuvier concluded, independently, that the bones belonged to an extinct species. Later the woolly mammoth was considered to be a distinct genus, and so renamed Mammuthus primigenius. [Source: ucmp.berkeley.edu]

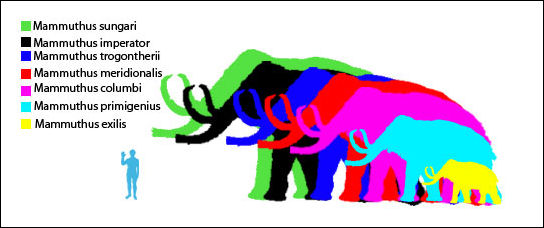

There were several species of mammoth. On those found in North Americas, Discovery News reported: “The woolly mammoth was a smaller furrier beast, that lived in the north closer to the glaciers of the Ice Ages, from Alaska through Canada, and east to the Great Lakes and New England. The larger Columbian mammoth lived further south. It inhabited the western and southern portion of the U.S. as far south as Florida, and nearly to Chiapas in Mexico. The mammoths should not be confused with the American mastodon (Mammut americanum), another ancient elephant from North and Central America. [Source: Discovery News, June 1, 2011]

Woolly mammoths evolved from steppe mammoths (Mammuthus trogontherii) in Siberia by around 600,000–500,000 years ago, replacing steppe mammoths in Europe by around 200,000 years ago, and migrated into North America during the Late Pleistocene. Steppe mammoths evolved in Eastern Asia around 1.7 million years ago.

See Separate Articles: STONE AGE ANIMALS: CAVE LIONS AND HYENAS AND GIANT APES factsanddetails.com ; WOOLLY RHINOS AND CAVE BEARS factsanddetails.com ; MAMMOTHS, HUMANS, HUNTING AND CLONING factsanddetails.com

Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age” by Adrian Lister and Paul G. Bahn (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History, from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us” by Steve Brusatte (2023) Amazon.com;

“How to Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-Extinction” (Princeton Science Library)

by Beth Shapiro Amazon.com;

“Mastodon, Mammoth, and Man” by John Patterson MacLean Amazon.com;

“Mammoths, Sabertooths, and Hominids: 65 Million Years of Mammalian Evolution in Europe” by Jordi Agustí and Mauricio Antón (2002) Amazon.com;

“Megafauna: First Victims of the Human-Caused Extinction by Baz Edmeades (2021) Amazon.com;

“Mega Meltdown: The Weird and Wonderful Animals of the Ice Age by Jack Tite Amazon.com;

“Animal World: Ice Age” by Camelot Editora, Francine Cervato, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Vanished Giants: The Lost World of the Ice Age” by Anthony J. Stuart (2024) Amazon.com;

“End of the Megafauna: The Fate of the World's Hugest, Fiercest, and Strangest Animals” by Ross D E MacPhee (Author), Peter Schouten (Illustrator) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History, from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us” by Steve Brusatte (2023) Amazon.com;

“Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age” by Adrian Lister and Paul G. Bahn (2015) Amazon.com;

“Smilodon: The Iconic Sabertooth” by Lars Werdelin, H. G. McDonald, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Giant Sloths and Sabertooth Cats: Extinct Mammals and the Archaeology of the Ice Age Great Basin by Donald Grayson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Clan of the Cave Bear: Earth's Children, Book One” by Jean M. Auel Amazon.com

Siberian Woolly Mammoths and Their Ivory

As the Siberian tundra melts, thousands of dead mammoths are emerging from the thawing permafrost — with perfectly preserved tusks. Russians are harvesting about 60 tonnes of ivory from them a year, a 2010 study said, suggesting the amount of mammoth ivory entering the global market exceeds that from elephants. [Source: Sunday Times, September 27, 2010]

engraving on a mammoth tusk

During the Pleistocene Era (10,000 to 180,000 years) ago, large numbers of Woolly mammoths roamed the forests and tundra of Siberia. When Ice-Age glaciers moved across Siberia, many Woolly mammoths fell into icy pools of water and were entombed in permafrost. Woolly mammoths thrived particularly well in Siberia, where they grazed on steppe grasses along with bisons and other large herbivores that in turn were fed on by cave lions, saber-toothed tigers and wolves. Animals of large size and with lots of hair thrived in the frigid weather. The animals endured through ice ages and periods of global warming.

In Siberia, Russians have made millions mining ice-preserved Woolly mammoth tusks from animals that died between 10,000 and 40,000 years ago. The brown grade ivory sold for US$150 a pound in 1992, compared to $400 for elephant ivory, and is legal since no animals are being killed. The ivory can be carved into figures. It is estimated that 600,000 tons of tusks may be frozen in Siberia. [National Geographic Earth Almanac, January 1992].

Woolly mammoth ivory is prized by carvers. An entire tusk can sell for as much as $50,000 at an auction. The sale of Woolly mammoth ivory is not illegal because the animal is already extinct. Sculptor Semen Pesterov is a ivory carver. But he doesn't use walrus or elephant ivory; he uses the tusks of extinct Woolly mammoth frozen in the Siberia permafrost.

During the summer teams outfit with amphibious vehicles, helicopters, river boats and truck head to the tundra in northeastern Siberia to search for the tusks of Woolly mammoths. The best finds are restored with auto body filler and varnish and sold on the international market. Lesser quality bones and tusks ate carved into chess sets and other items. The lowest quality pieces are ground into powder and used to make traditional Chinese medicines.

The best preserved Woolly mammoths fell into ice crevasses and were immediately frozen or drowned in small lakes, settling into the permafrost at the bottom. Rich mammoth hunting areas in Siberia include region around Chokurdakh, a settlement along the Indirka River, and Duvannyi Yar, near Cherski. Most of these places can only be reached by plane or helicopter. So many Woolly mammoth's been found that some people eat mammoth steaks. There are also stories of 200,000-year-old bison being found and the smell attracting wolves who ate the meat.

Woolly Mammoth Finds

A 216,000-year-old tooth, found along the Old Crow River in the Yukon territory in Canada, is the oldest-known woolly mammoth fossil in North America. Camilo Chacón-Duque, a researcher at the Centre for Palaeogenetics at Stockholm University in Sweden, told Live Science that the find was unusual because most North American mammoth specimens of this age likely belong to other species that existed before woolly mammoths. The oldest woolly mammoth DNA, from Russia, is around 1.3 million years old. The findings were published in April 9, 2025 in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.[Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, April 12, 2025]

The nearly complete carcass of an adult Woolly mammoth frozen 23,000 years ago in the Siberia permafrost of Taimyr Peninsula was dug out in September 1999 by a French-led expedition. The specimen was named the "Jarkov Mammoth" after nine-year old boy in the family of Siberian reindeer herders who found it. The Jarkov Mammoth stood 11 feet at the shoulder and was estimated to be around 40 years old. Encased in 23-ton block of ice and earth, the carcass was lifted by Russia's largest helicopter and flown to ice caves in Khatnga, Siberia where a sub-freezing laboratory was made. Scientists carefully defrosted the carcass over a period of months using hair dryers before studying it..

In November 2003, the well-preserved head of a Woolly mammoth was found frozen in the permafrost by hunters 1,200 kilometers north of Yakutsk, complete with eyes, ears and body hair, and part of its trunk. Its head and a well-preserved foot were displayed at the World Exposition in Aichi Japan in 2005. The were hopes that the specimen was in good enough shape that DNA could be extracted for cloning. Dima was the nave given to a 12,000-year-old Woolly mammoth found by fishermen in Siberia in 1977. In 2012, an 11 year old Russian kid discovered the remnants of what turned out to be a very well preserved 30,000 year old woolly mammoth in the area where he walked his dogs.

There are enough people studying mammoths to justify periodic international conference devoted entirely to them. Scientist are looking for samples in good enough condition so that the DNA is relatively intact and can be analyzed. DNA from 20,000- to 30,000-year-old mammoths as well as horses and musk oxen have been found in clumps of permafrost soil in Siberia.

frozen mammoth in Siberia

Woolly Mammoth Characteristics

Mammoths stood as tall as four meters (14 feet) at the shoulder. They had short tails, sloping backs and tusks that curved outward, then inward, They mostly grazed on grasses and had ridged teeth that were good for grinding. Similar in size and features to Asian elephants, except with more hair, adult woolly mammoths averaged approximately three meters (10 feet) tall and weighed about 5,450 kilograms (six tons. Newborns weighed approximately 90 kilograms (200 pounds) at birth. [Source: extinct-animals-facts.com]

The long prominent tusks of the woolly mammoth could reach up to 4.5 meters (15 feet) in length long. It has been theorized that they would have been used for pushing away ice and snow to get food as well as for fighting and defending. Similar to the rings on a tree, scientists can determine the age and health of a woolly mammoth by the rings on its tusks. Woolly mammoth calves had tusks, which contain information about what the animals ate. By examining calf tusks scientists determined that mammoths nursed with their mothers for at least five years.

According to the University of California, Berkeley: “The bones of fossil mammoths and mastodons can often look very similar — they are best differentiated on the basis of their teeth (compare mammoth and mastodon teeth by browsing the images at The Paleontology Portal). While mammoths had ridged molars, primarily for grazing on grasses, mastodon molars had blunt, cone-shaped cusps for browsing on trees and shrubs. Mastodons were smaller than mammoths, reaching about ten feet at the shoulder, and their tusks were straighter and more parallel. Mastodons were about the size of modern elephants, though their bodies were somewhat longer and their legs shorter.” [Source: ucmp.berkeley.edu]

Woolly Mammoth Adaptions for Cold

Woolly mammoth lived in extremely cold, arctic environments. They were well adapted to survive there. As their name suggests, they were covered with fur but what really kept them warm was about 10 centimeters (four inches) of pure fat for insulation underneath their skin.

Woolly mammoths had dense undercoat, with guard hairs up to three feet long, and small, fur-lined ears. Layers of coarse hairs protected this woolly insulation, forming a dense coat that could combat minus 20°F temperatures. As mammoths aged they developed cracks in their soles that provided traction in snow, while fleshy pads behind the toes that cushioned steps. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, May 2009]

The ears and tail of the woolly mammoth were relatively short so they would not get frostbite and to minimize heat loss. Modern day elephants have ears that extend 180 centimeters (71 inches) while those of woolly mammoths only extend about 30 centimeters (12 inches). Blood samples taken by scientists have determined that the hemoglobin of the woolly mammoth was adapted to the cold environment, allowing the animal's tissue to be supplied with oxygen no matter what the temperature.

Mammoths Had 'Anti-freeze Blood'

Mammoths had a form of "anti-freeze" blood to keep their bodies supplied with oxygen at freezing temperatures, an adaption that may have been crucial in allowing the ancestors of mammoths to exploit new, colder environments during Pleistocene times.. Paul Rincon of BBC wrote: “Nature Genetics reports that scientists "resurrected" a woolly mammoth blood protein to come to their finding. This protein, known as haemoglobin, is found in red blood cells, where it binds to and carries oxygen. The team found that mammoths possessed a genetic adaptation allowing their haemoglobin to release oxygen into the body even at low temperatures. The ability of haemoglobin to release oxygen to the body's tissues is generally inhibited by the cold. [Source: Paul Rincon, BBC News, May 2, 2010 |::|]

“The researchers sequenced haemoglobin genes from the DNA of three Siberian mammoths, tens of thousands of years old, which were preserved in the permafrost. The mammoth DNA sequences were converted into RNA (a molecule similar to DNA which is central to the production of proteins) and inserted into E. coli bacteria. The bacteria faithfully manufactured the mammoth protein. "The resulting haemoglobin molecules are no different than 'going back in time' and taking a blood sample from a real mammoth," said co-author Kevin Campbell, from the University of Manitoba in Canada. |::|

“Scientists then tested the "revived" mammoth proteins and found three distinctive changes in the haemoglobin sequence allowed mammoth blood to deliver oxygen to cells even at very low temperatures. This is something the haemoglobin in living elephants cannot do. "It has been remarkable to bring a complex protein from an extinct species back to life and discover important changes not found in any living species," said co-author Alan Cooper, director of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at the University of Adelaide. Without their genetic adaptation, mammoths would have lost more energy in winter, forcing them to replace that energy by eating more.” |::|

different kinds of mammoth

Woolly Mammoth Diet

Woolly mammoths were herbivores, eating a variety of grasses, leaves, fruits, berries, nuts, and twigs. The jaw and teeth of the woolly mammoth were more vertical than modern elephants and it is believed that it allowed them to more easily feed on grass.

According to the University of California, Berkeley: “ If mammoths were similar to elephants in their eating habits, they were very remarkable beasts.Consider the following facts about modern elephants: 1) spend 16 to 18 hours a day either feeding or moving toward a source of food or water; 2) consume between 130 to 660 pounds (60 to 300 kg) of food each day; 3) drink between 16 to 40 gallons (60 to 160 l) of water per day; 4) produce between 310 to 400 pounds (140 to 180 kg) of dung per day. “Since most mammoths were larger than modern elephants, these numbers must have been higher for mammoths! [Source: ucmp.berkeley.edu]

“From the preserved dung of Columbian mammoths found in a Utah cave, a mammoth’s diet consisted primarily of grasses, sedges, and rushes. Just percent included saltbush wood and fruits, cactus fragments, sagebrush wood, water birch, and blue spruce. So, though primarily a grazer, the Columbian mammoth did a bit of browsing as well.”

The intestines of a young mammoth contained the feces of an adult mammoth, probably her mother s: evidence that mammoth calves, like their modern elephant cousins, ate their mother s feces to inoculate their guts with her microbes in preparation for digesting plants.. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, May 2009]

Mother Mammoths Nursed Their Young for Three Years

Researchers, led by University of Western Ontario paleontologist Jessica Metcalfe, determined that mammoth infants were weaned as late as three years after birth based on studying woolly mammoth teeth found in northern Yukon. Randy Boswell wrote in Postmedia News: “That means they were nursed on mother's milk much longer than modern elephants, apparently in response to the prolonged darkness, scanty vegetation in their far-north habitat and the ever-present threat of being killed by prehistoric wildcats. [Source: Randy Boswell, Postmedia News, December 21, 2010 ]

“The team's findings, published in the latest issue of the journal Palaeo 3, highlight a previously unknown vulnerability in mammoths as the species struggled to adapt to climate change, attacks by predators (including humans) and other challenges that led to their disappearance at the end of the last ice age. "Today, a leading cause of infant elephant deaths in Myanmar is insufficient maternal milk production," the study states. "Woolly mammoths may have been more vulnerable to the effects of climate change and human hunting than modern elephants not only because of their harsher environment, but also because of the metabolic demands of lactation and prolonged nursing, especially during the longer winter months."

“Along with Yukon paleontologist Grant Zazula and UWO researcher Fred Longstaffe, Metcalfe examined the chemical composition of about two dozen preserved teeth from infant and adult mammoths found around Old Crow, a fossil-rich Yukon site well known for shedding light on ice-age ecology. The researchers concluded that the prolonged darkness in northern Canada, as well as the necessity of protecting young mammoths from night-hunting predators, such as the scimitar cat, were likely significant factors in shaping the physiology and maternal behaviour of mammoths. "In modern Africa, lions can hunt baby elephants but not adults. . . . They can kill babies and, by and large, they tend to be successful when they hunt at night because they have adapted night vision," Metcalfe stated in a summary of the study. "In Old Crow, where you have long, long hours of darkness, the infants are going to be more vulnerable, so the mothers nursed longer to keep them close."

““Because of the "relatively poor quantity and quality of plant food available on the mammoth steppe during winter, combined with the greater predation risk attributable to short daylight hours," conditions would have led young mammoths to "rely solely on milk" for as long as possible. But extended nursing of baby mammoths came with a cost, the researchers believe, as nutrition-challenged mothers fought a losing battle against the various forces driving the species toward extinction.

1,000-Kilometer Mammoth Migration Gleaned from 14,000-Year-Old Tusk

In January 2024, scientists announced they had retraced the migration of a female woolly mammoth from her birthplace in present-day Canada to eastern central Alaska, where she met her end around 14,000 years ago at the hands of hunter-gatherers. Sascha Pare wrote in Live Science: The mammoth, whose name Élmayuujey'eh translates to "hella lookin" in the aboriginal Kaska language, was likely killed by early Beringian hunter-gatherers when she was 20 years old. Her existence is known thanks to a complete tusk discovered at Swan Point, one of the oldest archaeological sites in the Americas. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, January 18, 2024]

Élmayuujey'eh, or Elma for short, was born toward the end of the last ice age in what is now the Canadian province of the Yukon, where she likely stayed for the first decade of her life. A new analysis of the mammoth's tusk suggests she then set off across the frozen landscape, covering roughly 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) in under three years. "That's a huge amount of movement for a single mammoth," study co-author Hendrik Poinar, a professor of anthropology at McMaster University in Canada and the director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Center, said in a video released by the university. Elma trekked all the way into Alaska and eventually slowed down, Poinar said. Her remains indicate she was closely related to both a juvenile and a newborn woolly mammoth whose bones were also unearthed at Swan Point. The trio may have belonged to one of two matriarchal herds that roamed an area within 6.2 miles (10 km) of Swan Point, according to the study, published January 17, 2024 in the journal Science Advances.

To piece Elma's life together, researchers split her tusk lengthwise and examined thin layers of ivory that formed like the rings of a tree trunk throughout her years. The proportion of different versions of chemical elements, or isotopes, in these layers contained valuable information about the mammoth's diet and location, enabling the team to retrace her steps. The researchers also analyzed ancient DNA in Elma's tusk and compared it with the remains of eight other woolly mammoths found in and around Swan Point, including the two youngsters. Their results revealed the mammoths belonged to at least two distinct herds that may have gathered in the region along with other mammoth herds — a congregation that would have attracted humans.

"Indigenous hunters clearly saw that the mammoths were using this as a really important location for feeding," Poinar said. "The data to me suggest that these were Indigenous people that appreciated, looked at, loved these phenomenal beasts walking on this landscape. But it would make sense too, that in times of need, that you would kill them — a mammoth like that could provide food for a huge number of people over a long period of time." Elma's remains indicate she was in the prime of early adulthood and well nourished at the time of her death. She likely died in late summer or early autumn, which coincides with when humans would have set up their seasonal hunting camp at Swan Point and suggests she died at the hands of hunters, according to the study.

Mammoth Carcass That Oozed Blood and Had Meat Fresh Enough to Eat

In May 2013, scientists from the Siberian Northeastern Federal University ventured to remote and city Maly Lyakhovsky Island in the far where they unearthed an almost complete mammoth, with three legs, most of the body, part of the head and the trunk still intact. During excavations, the carcass oozed a dark red liquid that turned out to be mammoth blood. Once freed of the permafrost, the mammoth meat was reportedly fresh enough that one of the scientists took a bite of it. "This is definitely one of the best samples people have ever found," Insung Hwang, a cloning scientist at the SOOAM Biotech Research Center, said. The researchers then took the carcass to Yakutsk in Russia, where a group of experts had just three days to thoroughly examine the specimen before it was refrozen to prevent rotting. [Source: Tia Ghose, LiveScience on November 17, 2014]

Tia Ghose wrote in LiveScience: The team used carbon dating to determine that the female mammoth, nicknamed Buttercup, lived about 40,000 years ago. Tests conducted on the mammoth's teeth revealed it was likely in its mid-50s. Based on growth rates from the tusks, the team deduced that the mammoth had also successfully weaned eight calves and lost one baby. Feces and bacteria in the intestines revealed the ancient matriarch ate grassland plants such as buttercups and dandelions.

Tooth marks on her bones helped the scientists glean information about Buttercup's grisly end. The mammoth had become trapped in a peat bog and was eaten alive from the back by predators such as wolves. While scientists probed the elbow of the mammoth, the large beast oozed more blood. Chemical analyses revealed that the blood cells were broken, but still contained hemoglobin, or oxygen-ferrying molecules. Unlike humans and other mammals, mammoths evolved a cold-resistant form of hemoglobin that could survive at the near-freezing temperatures present during the Ice Age. "The fact that blood has been found is promising for us, because it just tells us how good of a condition the mammoth was kept in for 43,000 years," Hwang said.

DNA is fragile and must be stored at low temperatures and in uniform humidity to stay intact. Past mammoth carcasses have looked exceptionally well-preserved, with some even yielding a preserved mammoth brain. Others have oozed what looked like blood, but ultimately did not have enough DNA to recreate the mammoth genome and clone it.

Lyuba

In 2007, a female mammoth — nicknamed Lyuba after the Nenet herder who discovered her — was found in the Russian Arctic’s Yamalo-Nenetsk region. She died at the age of six months and had been frozen for around 40,000 years. Weighing 50 kilograms (110 pounds), and measuring 85 centimeters high and 130 centimeters from trunk to tail, the young mammoth, was roughly the same size as a large dog. Her flesh, internal organs, stomach contents, bones, milk tusks and other teeth were all intact. A CT scan provided detailed insights into her anatomy and offered clues to how she died. Sediment found blocking the trunk’s nasal passages and in the mouth , esophagus, and windpipe suggests that she asphyxiated by inhaling mud after becoming trapped in a mire. [Source: Dmitry Solovyov, Reuters, July 11, 2007]

“When I saw her,” University of Michigan scientists Dan Fisher said, “my first thought was, Oh my goodness, she’s perfect — even her eyelashes are there! It looked like shed just drifted off to sleep. Suddenly, what Id been struggling to visualize for so long was lying right there for me to touch.” Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: Other than the missing hair and toenails, and the damage shed sustained after her discovery, the only flaw in her pristine appearance was a curious dent in her face, just above the trunk. But her general appearance and the healthy hump of fat on the back of her neck suggested the baby had been in excellent condition at the time of her death. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, May 2009]

Lyubas premolars and tusk revealed she had been born in the late spring and was only a month old when she died. The last layers of her tusk matched the pattern that Fisher associates with accidental death: a series of even, prosperous days, coming to an abrupt end. Like tiny time capsules , Lyuba’s teeth hold a detailed diary of her brief life. Oxygen isotopes in the dentin of her second and third premolars and other teeth reveal she was born in spring. By comparing her body size and degree of tusk development with that of elephants, scientists originally estimated her age at four months. But by slicing open the second premolar and analyzing its growth lines — similar to the rings in a tree — they found that only one month had passed between her birth and death..

Lyuba Autopsy

Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: On June 4, 2008, in a genetics laboratory in St. Petersburg, Russia, scientists began a marathon, threeday series of tests and surgical procedures on Lyuba. As she lay on a Plexiglas light table in the middle of the room, Naoki Suzuki of the Jikei University School of Medicine inserted an endoscope into her abdominal cavity, to explore an open space he’d seen during the CT scan. Other scientists used an electric drill to take a core sample of the hump of fat on the back of her neck, searched for mites in her ears and hair, cut into her abdomen, and removed sections of her intestine to study what she had been eating. Finally, on the third day, Fisher cut into Lyuba’s face and extracted a milk tusk, as well as four premolars. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, May 2009]

Initially the researchers kept her frozen by surrounding her with plastic tubs of dry ice. Later, to facilitate the more invasive procedures, they allowed her to slowly thaw out, carefully monitoring her for signs of putrefaction. The scientists cut a patch of skin and fat from Lyuba's abdomen. “This tells us as much about the mother as the baby” said Fisher, noting that the healthy layer of white fat indicates the nursing calf was well fed. “If the mother had been ill or struggling to find food, we would expect this layer to be much thinner ” had to cram so much work into so little time. I just made a mental note and moved on” He also noticed that the mammoths teeth were not held in their sockets by the usual connective tissue, and her muscles had separated from the bone in places where, in a normal specimen, they would have been firmly bonded.

The x-ray-opaque areas visible on the CT scan turned out to be brilliant blue crystals of vivianite, probably formed from phosphate leached out of her bones. Fisher noted a dense mix of clay and sand in her mouth and throat, which would support the hypothesis from the CT scan that she’d suffocated, probably in riverbank mud. In fact, the sediment in Lyubas trunk was packed so tightly that Fisher saw it as. a possible explanation for the dent in her face. If she were frantically fighting for breath and inhaled convulsively, perhaps a partial vacuum was created in the base of her trunk, flattening its soft tissues against her forehead..

Lyuba was probably killed by a misstep in or near a muddy river, and preserved for science by a combination of biochemical serendipity and the singular resolve of a Nenets herder...Her healthy, well-fed state was echoed in the record of her dental development. Analysis of her well-preserved DNA has revealed that she belonged to a distinct population of Mammuthus primigenius that, soon after her time, would be replaced by another population migrating to Siberia from North America.

Study of Lyuba’s Tusks

Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: Fisher was particularly excited about one specific part of Lyubas anatomy: her milk tusks. Tusks are modified incisors that grow continuously in layers throughout an animals life. Over 30 years of studying mammoth tusks, Fisher had figured out that these deposits were laid down in yearly, weekly, and even daily increments, and that, like the rings of a tree, they contained a detailed record of the animal’s life history. Thick layers represented rich summer grazing, while thin ones indicated sparse winter fare. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, May 2009]

From a sudden narrowing of the strata around the 12th year, Fisher could discern when a young male became sexually mature and was driven away by its mother from the matriarchal herd; some years later came signs of the ferocious musth battles that adult males waged to determine who would win the opportunity to mate. Finally, in the layers at the root of the tusk that are the last to form, Fisher found dues to how an animal died — a slow dwindling caused by injury, illness, or environmental stress, or the sharp break of sudden death. He also found that the levels of certain chemical elements and isotopes in the tusks provided data on the animals diet, climatic situation, even major changes in location such as migration..

One problem with interpreting mammoth tusks, however, was that they almost never came with mammoths attached, making it hard for Fisher to test his inferences about health and age. Lyubas superb state of preservation promised to change that. By giving direct evidence of her diet and state of health, her stomach and intestinal contents and the amount of fat on her body could provide an independent corroboration of the brief dietary “journal” recorded in her still unerupted milk tusks. “In this case we don’t need a time machine to see how accurate our work is,” Fisher says. Moreover, since the milk tusks grow from early in gestation to around the time of birth, Lyuba could shed new light on a critical period in a mammoth’s life: the time in the womb (estimated to be 22 months, based on an elephant’s gestation length), followed by birth. A traumatic event for any mammal, the moment of birth is recorded in tooth microstructure by a distinct neonatal line. By comparing her milk tusk development with that of elephants, the scientists initially estimated her age at death to be four months. Counting the increments of ivory laid down after the neonatal line would provide a much more accurate age. in her face, “That feature immediately leaped out, though at the time I had no idea what to make of it,” Fisher says..

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except dwarf mammoth, Nature

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025