Home | Category: Monks, Nuns and Relics

SHROUD OF TURIN

Shroud of Turin

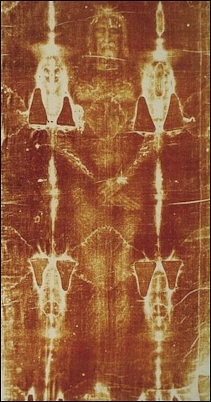

The Shroud of Turin is a mysterious 4.34-meter-long (14-foot-3-inch-long), 1.09-meter-wide (3-foot-7-inch-wide) piece of ivory-colored linen that is believed to be the shroud in which Christ's body was wrapped after the crucifixion. Imprinted on the shroud is a brownish-yellowish outline of a naked bearded man, with long hair and his hands modestly covering his groin, said to be Jesus Christ himself. The Catholic church makes no claims to its authenticity, but says it is a powerful symbol of Christ’s suffering. [Source: Kenneth Weaver, National Geographic, June 1980]

The shroud is owned by the Vatican and can not be viewed. It is rolled in red silk and rests in a silver-bound reliquary, placed high above a marble altar in a locked chamber of the Renaissance Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist (San Giovanni Battista) in Turin. When it was displayed in 2000 about 1 million people turned up to see it. Another showing occurred in 2010. About 2 million people came out to see in 2015.

Radiocarbon dating suggests that at least parts of the relic date to Medieval times, suggesting it was an elaborate hoax created to beguile 14th-century believers. Subsequent research has revealed that However, follow-up research found the shroud could be much older — dating to between 280 B.C. to A.D. 220 — well within Jesus's lifespan. The debate rages on about the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin.

Websites and Resources on Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Internet Medieval Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Saints and Their Legends: A Selection of Saints libmma.contentdm ; Lives of the Saints - Orthodox Church in America oca.org/saints/lives ; Lives of the Saints: Catholic.org catholicism.org ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Truth About the Shroud of Turin: Solving the Mystery” by Robert K. Wilcox, Jeremy Edwin Gage, et a Amazon.com

“Witnesses to Mystery: Investigations into Christ's Relics” by Grzegorz Gorny and Janusz Rosikon Amazon.com ;

“Relics: What They Are and Why They Matter” by Joan Carroll Cruz Amazon.com ;

“Rag and Bone: A Journey Among the World’s Holy Dead” by Peter Manseau Amazon.com ;

“Saints Preserved” by Thomas J. Craughwel Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief” by Richard Barber Amazon.com ;

“Ark of the Covenant Pamphlet: Purpose and Symbolism of the Ark” by Rose Publishing Amazon.com

Image on the Shroud of Turin

The long and narrow shroud has images of both a man's front side and backside which are amazingly clear. The man has long hair and beard and six hands are crossed over his crotch. No one knows how the image was made and scientists have been unable to reproduce it.

The man’s faces appears swollen from blows. Up and down both sides of the man's legs and torso are scourge marks from whip lashings. At the end of the marks there appears to be contusions consist with wounds made by a Roman whip called a flagrum. There is even dried blood around the image's head, wrists, legs and left side which match up with the crown of thorns, crucifixion nails and lance wound that Christ sustained as he walked to Cavalry.

The image shows markings of a Roman crucifixion (the nails were in the wrists not the hands). Some scholars have said that over the eyebrows are impressions of coins with the name Tiberius Ceasar, dating from A.D. 30-31. Other scholars have suggested the image could have been made been with oils used to anoint Jesus's body and the intense heat created during resurrection (but images left behind by heated oils are different than those on the shroud).

History of the Shroud of Turin

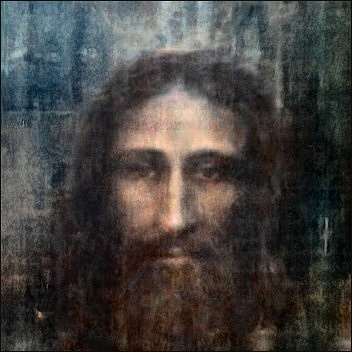

artist impression of the man in the Shroud of Turin

The shroud has been surrounded by controversy ever since it was its first recorded display in 1349 in France. The shroud was brought back by French knight Geoffrey de Charny from Constantinople after it was sacked during the Forth Crusade. He didn't say how he got it. Presumable it arrived in Constantinople, the capital of Christendom for more than a thousand years, from the Holy Land. Around 1400 it was declared a fraud by a French bishop.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The first solid historical evidence of its existence comes from 1390 when Bishop Pierre d’Arcis wrote to Pope Clement VII stating that the Shroud is a forgery and that its creator had confessed to having created it. There are some references to a shroud owned by a French knight earlier in the 14th century and to a burial cloth that was owned by the Byzantine emperors before the sack of Constantinople in 1204, but there’s nothing definitive linking either of these to the Shroud people venerate today. In fact several French churches also claim to own pieces of the shroud of Jesus, but they simply aren’t as famous. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 24, 2019]

Certainly Jesus was buried in a burial cloth of some sort. Three of the New Testament gospel writers mention that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus in a piece of linen cloth and placed it in his family tomb. The fourth, the Gospel of John, describes Peter finding pieces of burial cloth (one for the head and another for the body) in the empty tomb. There is a reference to (resurrected) Jesus giving the linen cloth to a servant of the Jewish high priest in a second century apocryphal text called the Gospel according to the Hebrews. This shouldn’t be considered historical, however. Dr. Andrew Gregory, author of a commentary on the text, writes that this story was written “to accentuate the [priest’s] wilful unbelief in the resurrection.” In other words, it’s part of an early Christian project against Jewish leadership. Some historians, like John Dominic Crossan, think that the whole story of Jesus’ burial is a fiction. Most who find the burial story credible would state that there was a burial shroud, but we don’t know what happened to it.

In any case, there’s a more than 1350-year gap between the use of a burial shroud and its appearance in the 14th century. Assuming they knew about its survival, it is somewhat strange that early Christians and theologians don’t mention the Shroud. A considerable amount of attention is paid to the ‘discovery’ of the true cross in Jerusalem. Why would ancient historians have passed over this detail? We have to assume that they didn’t know about it. This is something for which it is difficult to account but absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

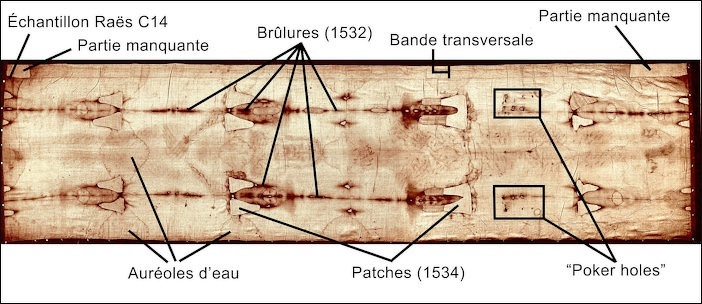

From the 14th century onwards, the Shroud’s ownership history is well documented: In 1432, the shroud was purchased by the House of Savory, the source of many Italian kings, A fire in 1532 nearly destroyed the shroud. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary dropped on it and the clothe still bears scorch marks from the incident. It arrived in Turin in 1578. It was placed in a baroque chapel, built by the Duke of Savoy, where it has been on display since the 17th century and continues to reside today.

In 1898, the first photographs of the shroud were taken. The photographer who took them was astonished to find the image was more visible on a photograph and it was a negative image. During World War II it was taken out of harms way to southern Italy. In March 1983, the shroud became the possession of The Vatican after the death of Umberto II, the exiled last king of Italy, who willed it the Holy See.

Evidence that the Shroud of Turin is Fake

Scientists were allowed to examine the Shroud of Turin during a 1978 exhibition. A U.S. team studied it non-stop for 120 hours with $2.5 million of equipment and spent 150,000 man hours doing analysis and study. Carbon testing was not allowed on the grounds that a valuable fragment was needed for the testing and it is destroyed in the test. Even if the shroud turns out to be 2000 years old would be impossible without divine intervention or a great technological breakthrough to determine whether the shroud holds the image of Jesus himself.

Shroud of Turin on display

Carbon 14 testing was finally done on some of the shrouds threads in 1988 at three laboratories based at top universities. The results were collected and collated by the British Museum in London and published with great fanfare in an article in the prestigious Nature magazine, claiming to offer definitive proof that the Shroud was a medieval fraud. The test concluded that the Shroud of Turin was woven from flax harvested between A.D. 1262 and A.D. 1390, which means the 4.3 meter (14-foot) shroud could not be Christ's burial cloth, unless the power of God can transcend time.

Moss wrote: Even though it was unlikely to be real, most people thought that the radiocarbon dating would be the silver bullet that would either confirm the inauthenticity of the Shroud or dispel Shroud doubters once and for all. Vatican agreement for testing took decades to obtain and then, finally, in 1987, laboratories in Arizona, Oxford, and Zurich were selected to perform independent tests. On April 21, 1988, a sample was taken from one corner of the cloth and distributed to the three sets of scientists. The resulting publication declared that there was “conclusive evidence” that the linen of the shroud dates to 1260-1390 CE with 95 percent confidence in those results.

Pieces of the shroud analyzed by the laboratories at Oxford, Arizona and Zurich all came up with the same dates. Some scholars maintain the blood was made by red ocher or red pigment rather blood. Other have recreated similar shrouds using various techniques. Even the Vatican admitted the shroud could not be what it is claimed to be.

In October 2009 an Italian group called the Committee for Checking Claims of the Paranormal announced that it had figured out a way to duplicate the images made on the Shroud of Turin. The lead scientist Luigi Garlaschelli said the team used a line woven with the same technique as the shroud and artificially aged it by heating it in a an oven and washing it with water. The clothe was then placed on a student who wore a mask to reproduce the face and rubbed with red ocher.

Evidence that the Shroud of Turin in Genuine

The scientist in 1978 concluded that image on the Shroud of Turin was not painted on and they couln't explain how it was made; that the "blood" responded to X-ray analysis, thermography and chemical analysis the same way real Type AB blood does; and that it was not a forgery based on the conclusuion that an image like the one on the shroud could not be made using any known method.

Some scientists have suggested that the carbon dating done in 1988 may have been affected by the 1532 fire or microorganism that had attached themselves to the cloth in recent centuries. Carbon dating works only on samples less than 5,730 year old. After a living things dies that ratio of Carbon 14 isotopes to Carbon 12 isotopes decays at a known rate. The measurement of this ratio with a high energy mass spectrometer reveals the date.

In 1997, scientists reported that pollen found on the shroud matches that of plant species found only in the Palestine area. Analysis done in 1999 at the Hebrew International University showed that the pollen came from around the Jerusalem area sometime before the 8th century.

Pollen grain found in the shroud matches grains found on the Sudarium of Oviedo, a relic kept at the Cathedral in Oviedo Spain. The sudarium has been dated to the first century and has also been described as the burial facial cloth of Jesus. Both the shroud and the sudarium appear to carry type AB blood, plus they have the same pattern of blood stain and the same kinds of pollen.

There are no traces of any paint on the shroud. The image is a negative. It is unlikely medieval forgers could have made such an image, they had no knowledge of photography. The body was prepared in a way that is consistent with burials in Jesus's time (except some scholars believe hand were folded across the chest not placed on the groin).

John Jackson, a physicist at the University of Colorado, has hypothesized the cloth was contaminated by high levels of carbon monoxide and the this caused the carbon-14 tests to be off. His assertion has been taken seriously enough that Oxford has said it will work with him to get permission to test the shroud again. In addition, Los Alamos National Laboratory presented research that the 1988 finding might be off because the piece of cloth sample might be a medieval addition added during repairs. Jackson also asserts that there is too much evidence that the shroud is older than Carbon 14 tests concluded and the matter needs a fresh look.

Doubts and Stonewalling in Regard to the 1988 Shroud of Turin Radio Carbon Testing

Strangely, the original data from the 1988 radio carbon testing was not made available to researchers. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast:.In 2017, a legal request under the Freedom of Information Act obtained the raw information for the first time. Their results, published recently in Archaeometry, show that the issue of the dating of the Turin Shroud is far from settled. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 24, 2019]

Since 2005, a growing number of scholars have questioned the results of the 1988 tests. Some claimed, for example, that the area tested was a portion of the cloth that was repaired and that the tested strands reflect those repairs. We know, for example, that efforts were made to restore the Shroud in the 16th century. The fact that testing only used samples from one corner of the cloth makes it impossible to know if this is a claim is correct or not.

None academic institutions involved or the British Museum would respond to requests for the original raw data that were held in their archives. (The British Museum also did not respond to a request for comment from The Daily Beast.) It was only when Tristan Casabianca made a request under British law that he received a favourable reply. According to his co-authored article in Archaeometry, the British Museum “made all its files [hundreds of pages worth] ‘not dated or arranged in any order,’ available” to his team.

What Casabianca and co-authors Emanuela Marinelli, Giuseppe Pernagallo, and Benedetto Torrisi discovered is that the results were less conclusive than the Nature article suggests. Casabianca told the Daily Beast that they “examined not only the measurements not included in the Nature article but also the reports and letters from and to the laboratories which mention, for example, foreign material in the samples.” The Shroud might still be medieval, but earlier dates—while statistical outliers—should not be ruled out. Given that technologies of testing have improved in the past 30 years it is possible to make a case for re-testing. Casabianca told me he would like to see an interdisciplinary approach to dating the Shroud employed in any future testing. “Non-destructive tests should be a priority,” he added, suggesting that any future study could carbon date small burned scraps recently removed from the Shroud as part of the restoration process. This hypothetical future testing would need the approval and consent of Pope Francis who, thus far, has hedged his bets on the Shroud. He previously called it an “icon” rather than a relic.

For skeptics, efforts to re-test the Shroud and demonstrate its authenticity are the work of those who have a religious stake in the cloth’s authenticity. Even before his recent article, Casabianca had published a historiographical article on the Shroud’s authenticity and the next event he is hosting on the Turin Shroud will be held at the controversial and decidedly religious Museum of the Bible in January 2020.

What should interest everyone is how hard it was for researchers to obtain copies of the raw data produced during the radiocarbon testing. The British Museum had repeatedly denied requests for the raw data. Bioarchaeologist Dr. Kristina Killgrove, who was not involved in working on the Turin Shroud, told The Daily Beast that “it makes some sense to release info to researchers who want to check it / build on it (and not to release data completely publicly). But to refuse to release data is a big red flag.” Making data available publicly is important Killgrove added, because “replicability is the cornerstone of science, and science can’t progress without the publication of raw data.”

Given everything that is at stake in the Shroud it’s easy to see why scientists would be reluctant to release all of their results (as there are always statistical outliers). It’s also easy to understand why people of faith might be concerned by the strange reluctance of scientists to release their results in full. Perhaps new testing is needed to put the debate to bed once and for all.

Storage and Rescue of the Shroud of Turin

The shroud is normally rolled up and kept in a silver reliquary, which in turn is sealed behind bulletproof glass. A computer controls the climate inside, making adjustments for humidity and temperature. The shroud itself is so fragile it has been stitched to a white lining to keep it from disintegrating. It is no longer rolled up but should no be exposed to light.

In April 1997, a fire destroyed most of the church that houses the shroud. Turin firefighter Mario Trematore had to break though three layers of bulletproof glass case with a sledgehammer to rescue the shroud. "I was afraid for the shroud,: the fireman told the New York Times, "because when I smashed through the glass, I could easily smash the casket and the shroud, and then I would have been known as the biggest cretin in the world."

Trematore said in an another interview, "A force in the cloth...was the faith of millions of believers, not my own; I knew I had to save the shroud for them, not for me. Before then, I was an indifferent Catholic, but that moment changed my life. When I carried away the shroud in the silver case, it was incredibly light, like a newborn child. I felt like the donkey carrying Jesus into Jerusalem."

Displaying the Shroud of Turin

In the fall of 1978 the Shroud of Turin was displayed for six weeks inside a bullet-proof glass and steel case and over three million people came to see it. Some waited in line 16 hours to see it. Before 1978, it was shown only in 1931 and 1933.

The shroud was displayed from mid April to mid June 1998. It was hung lengthwise over a purple drapery in the dark nave of Turin Cathedral. Tens of thousands of people visited each day. Each person was allowed to view it for two minutes before being asked to move on. Among those who saw it were Pope John Paul II. Another showing was held in 2000, a Holy Year for the Roman Catholic Church.

More than 500 books have been written on the Shroud of Turin. There are also a bunch of web sites.

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Medieval Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024