Home | Category: The Gospels and Early Christian Texts

GOSPEL OF MATTHEW

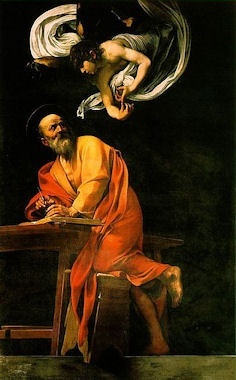

Inspiration of Saint Matthew by Caravaggio

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: “The evangelist who composed the gospel of Matthew was probably a Jewish Christian, possibly a scribe. The historical evidence suggests that he wrote between 80 and 90 CE and addressed his work to a community in conflict: Jewish Christians who were being pushed out of the larger communities, located in northern Galilee or Syria. These communities were led by Pharisees, rabbis who assumed leadership of the Jewish people in the aftermath of the destruction of Jerusalem. [Source: Marilyn Mellowes, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Matthew is at pains to place his community squarely within its Jewish heritage, and to portray a Jesus whose Jewish identity is beyond doubt. He begins by tracing Jesus' genealogy. To do this, Matthew only needed to show that Jesus was a descendent of King David. But Matthew takes no chances. He traces Jesus' lineage all the way back to Abraham. In the words of Helmut Koester, "It is very important for Matthew that Jesus is the son of Abraham." In short, Jesus is a Jew.

Matthew grounds his entire work in the traditions of Judaism. Matthew's narrative includes most of Mark's gospel but is supplemented with sayings material, another written source known as "M," and possibly other material as well. But even through the evangelist includes miracle stories, his main concern is to present Jesus as a teacher even greater than Moses. Accordingly, Matthew uses his sources to create a somewhat different narrative in which Jesus repeated instructs the people.

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Bible: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rose Guide to the Gospels: Side-by-Side Charts” Amazon.com ;

“What the Gospels Meant” by Garry Wills Amazon.com ;

“Why Four Gospels?” by A. W. Pink Amazon.com ;

"New Testament with Psalms and Proverbs", Pocket-Sized (New International Version, NIV,version) , Amazon.com ;

“A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New” by G. K. Beale Amazon.com ;

“Johnny Cash Reading the Complete New Testament” Amazon.com ;

“The New Testament in Its World: An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians” by N. T. Wright and Michael F. Bird Amazon.com ;

“King James Version Bible”, Black Leather-Look (imitation leather) Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Bible in English easy to read version” Amazon.com ;

“Eerdman's Dictionary of the Bible” by David Noel Eerdman Amazon.com ;

“How to Read the Bible” by James Kugel Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Bible: The Story of the World's Most Influential Book”

by John Barton, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Who Wrote the Bible?” by Richard Friedman, Julian Smith, et al.

Amazon.com ;

“The Complete Guide to the Bible” by Stephen M. Miller Amazon.com ;

“Oxford History of the Biblical World” by Michael D. Coogan Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce Metzger and Michael D. Coogan Amazon.com

Jesus’s Message in Matthew

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: “In Matthew's gospel, Jesus delivers five major speeches, which parallel the five great books of Moses known as the Pentateuch. The first and most important of Jesus' speeches is the Sermon on the Mount. One of the intriguing characteristics of this address is Jesus' repetition of the words, "you have heard it said . . . But I say to you." Matthew is giving a new interpretation to the Law; he is establishing the church as the new Israel. Matthew's concern about the state of the church is reflected in the way he tells the story of Jesus stilling the storm. In Greek, the word "storm" actually means earthquake. According to one interpretation, this story is really a metaphor: the disciples represent the Christian community, the boat is the church. In the face of upheaval and uncertainty that challenges faith and threatens to undo the church, Jesus gives assurance to the faithful: "Behold, I am with you until the end of days." [Source: Marilyn Mellowes, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Matthew refashions the final scene of Mark's story. The women come to the tomb and discover that Jesus is gone. But this time the angel instructs them to tell the disciples that he has risen. Then Jesus himself appears before the women and directs them to tell the disciples to meet him in Galilee. The disciples go the mountain — just as Jesus himself had once ascended the mountain to deliver the Sermon on the Mount — and they encounter Jesus. But some of them have doubts. Is it really him? Jesus reassures them: "All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth." And he also instructs them: "Go therefore and teach all Nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost."

“Notice that Jesus does not tell the disciples to only go only to "Israel" or to the "lost sheep of the house of Israel." He tells them to go to "the Nations" — to all peoples. For the Kingdom which Jesus has promised will embrace both Jew and gentile alike.”

Jesus in Matthew - a Man from Israel

Resurrection Matthew 28: 1-18

Professor Helmut Koester told PBS: “The Gospel of Matthew is concerned with the position of these early Christian churches within Israel, or in its relationship to what we call Judaism. And these are concerns that belong to the time after the fall of Jerusalem. How do these Christian communities, who don't even call themselves Christian, and probably don't even have a consciousness that they're something different than Israel, how do they relate to others who claim to be Israel? And it's very important that Jesus for Matthew is fully a man from Israel. Therefore, Matthew begins his gospel by taking all the genealogy of Jesus; he wanted to show that Jesus was the son of David, and now traces this back to Abraham. For Matthew, Jesus is not the son of David, but he is the son of Abraham. He is truly a man from Israel. And thus Jesus' teaching also is one that is fully in the legitimate tradition of Israel's teaching of the law. So in Matthew, not in any other gospel, we have Jesus saying he has not come to dissolve the law but to fulfill it. And that no part of the law will disappear.... [Source: Helmut Koester, John H. Morison Professor of New Testament Studies and Winn Professor of Ecclesiastical History Harvard Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Matthew has some hesitation to show that this is also the community for the gentiles. It is clear that yes, there is the gospel for the gentiles. The disciples at the end of the gospels are sent out to all nations, and are asked to teach them what Jesus had taught the disciples. That is, teach them also that Jesus had not come to dissolve the law. Now apparently the understanding of the law is not identical with that of emerging Judaism after the destruction of Jerusalem. Because notice there's no emphasis on ritual law. No circumcision, no Sabbath commandment. So the ritual commandments of the law have disappeared. But nevertheless, Matthew wants this to be understood as a legitimate new interpretation of the law of Moses.

Matthew's Jewish Christian Community

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: “Matthew's community subscribed to the Law, but they saw Jesus — not the Pharisees — as the rightful interpreter of the Law. This conviction tended to undermine the legitimacy and authority of the Pharisees who criticized the followers of Jesus. Now Matthew makes the Pharisees the "hypocrites": "Woe to you scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites. For you are like white washed tombs which on the outside look beautiful but inside they are full of the bones of the dead and all kinds of filth." (MATT 23:27) [Source: Marilyn Mellowes, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

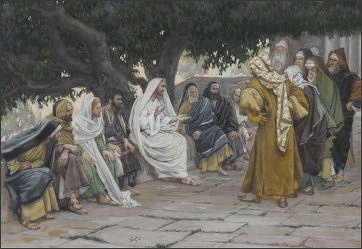

Jesus with the Pharisees and Saduccees

“Matthew's attitude toward the Pharisees is reflected in the way he tells the story of the death of Jesus. Pontius Pilate is portrayed as a sympathetic figure, and the blame is squarely placed on the Jewish leaders. But the fact that Jesus is pronounced dead leaves the Pharisees still worried. Jesus had predicted that "After three days I will rise again." (MATT 27:63). They imagine a scenario in which the followers of Jesus steal his body from the tomb in order to vindicate his claims. Pilate suggests that they seal the tomb with a large stone.

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: “Matthew's gospel is clearly written for a Jewish Christian audience living within the immediate proximity of the homeland itself. Matthew's is the most Jewish of all the gospels. The community for which Matthew was written was a Jewish Christian community that was encountering some new tensions in the period of reconstruction after the first revolt. It would appear that they've been there for quite some time. They actually show a consciousness of an older legacy of Jesus' tradition, going back to before the war. But now they're experiencing new tensions and new problems in the aftermath of the revolt as a political and social reconstruction is taking place. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“What may lie behind the social tensions reflected in Matthew's gospel may be the massive population shift that resulted after the first revolt. When most of the Jewish population moved to the Galilean region of north. That's the situation [in] which Matthew's gospel seems to be written. But, as this new population has to be organized, the new political realities of village life begin to produce some new tensions, as well. It's in this context that the Pharisaic movement would become the new dominant force for the reconstruction of Jewish life and thought in the period after the first revolt. From the early Pharisaic tradition would emerge the Rabbinic tradition and ...the Rabbis as the leaders and teachers of Jewish tradition and interpreters of Torah, of law, would set the stage for the normative development of Judaism, down to modern times.

Conflict in Matthew's Community

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: “Now, we have to remember that it's precisely in Matthew's gospel that the Pharisees are Jesus' main opponents throughout his life. Now, in Jesus' own times, the Pharisees weren't that prominent a group. Why does Matthew tell the story this way, so that a group that was less consequential during Jesus' own life time now becomes the main opponent? It's precisely because that's what's going on in the life of Matthew's community after the war. The Pharisees are becoming their opponents and we're watching two Jewish groups, Matthew's Christian Jewish group and the local Pharisaic groups in tension over what would be the future of Judaism. Naturally, they have very different answers. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Sermon on the Mount

“Matthew's community observes Torah. In Matthew, in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says, "think not that I've come to destroy the law and the prophets - I've come not to destroy them but to fulfill them." In Matthew, Jesus is a proponent of Torah piety, just like the Pharisees. So, on the one hand, they follow the law in a way that makes them very good Jews. On the other hand, there are tensions over what is the proper form of piety for them.

“One of the indications of the situation of Matthew's community comes up when Matthew's gospel gives regulations for how to discipline members within the community if they get out of hand. It says if one of the members of the congregation sins, go and tell them about it, and if they refuse to listen to you, take a friend and tell them about it and if they refuse to listen to them, take them to the church and if they refuse, kick them out. You actually throw them out of the church, out of the congregation. But, what's really interesting in this, this set of disciplinary regulations from Matthew 18, is that when you kick them out, when you excommunicate them or disfellowship them, you say, "you now are a gentile and a tax collector." You treat them as an outsider. But if kicking someone out means they're considered a gentile, those who are inside clearly must think of themselves still as thoroughly Jewish.

“The way Matthew then tells the story of Jesus draws on a lot of symbols from Jewish tradition that really convey a picture of Jesus. Jesus goes up on to a mountain to teach and there talks about the law. He looks like Moses. Jesus delivers five different sermons of this sort, just like the five books of Torah. There are a lot of elements in this story that resemble Moses' traditions, from the killing of the babies, in the birth narrative, to the Sermon on the Mount, to even to the way that Jesus dies, just like some of the prophets died, as martyrs to their prophetic calling.

Gospel of Luke

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “Traditions report that Luke was a companion of Paul, a physician and therefore someone learned in Hellenistic literary and scientific culture. All of those are secondary traditions and most scholars view them as somewhat unreliable. What we can infer from the evidence of the Book of Acts and the third gospel is that the author was someone who was steeped in scripture, in the Septuagint, and who was aware of Hellenistic literary patterns, historiographical and novelistic. And these kinds of patterns certainly have an impact on his literary products. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: “The author of Matthew wrote of a Kingdom that would embrace Jews and gentiles alike. The author of Luke wrote for a community which also awaited the arrival of God's Kingdom, but which was concerned about its life in another Kingdom, the Kingdom of Caesar. The question they faced was this: can Christians who believe in the Kingdom of God also be loyal subjects of the Roman Empire? Luke's unequivocal answer was "Yes." [Source: Marilyn Mellowes, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Luke

“It has also deeply influenced how the later church came to imagine the birth of Jesus. For it is Luke who presents the familiar tale of his birth: "And in those days, a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be taxed." (LK 2:1) Luke describes how Joseph and Mary journeyed from Nazareth, in the region of Galilee into Judea, to Bethlehem. Why does Luke tell the story this way? Scholars speculate that he is placing the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem because Bethlehem is the city of King David; Luke is drawing a direct parallel between the first king of Israel and the new King, Jesus Christ.

Luke

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “Luke wrote two works, the third gospel, an account of the life and teachings of Jesus, and the Book of Acts, which is an account of the growth and expansion of Christianity after the death of Jesus down through close to the end of the ministry of Paul. Luke was probably writing in the latter decades of the first century, probably in a thoroughly Hellenistic environment. Scholars speculate on whether the gospel was written in Antioch, which would have been a significant Hellenistic city, or in Asia Minor, in places like Ephesus or Smyrna. In either case, Luke would have been in touch with, and very heavily in dialogue with, Hellenistic culture broadly conceived. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: “Tradition holds that the author of the gospel of Luke was a physician and a traveling companion of the apostle Paul. History offers no evidence to substantiate these claims, but the work itself suggests that it was composed by someone who lived in one of the cities where Paul had established his early churches. The composition and language of the work suggests that its author was well-educated, fluent in Greek, and possessed a keen sense of literary style. [Source: Marilyn Mellowes, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Whoever wrote Luke wrote more than a gospel; he also wrote the Book of Acts, an account of the growth and expansion of Christianity after the death of Jesus through the end of the ministry of the apostle Paul. In fact, many scholars insist that Luke's gospel is just the first half of a two-part story that begins with Jesus in Nazareth and ends with Paul in Rome. In the words of Mike White, "He is telling a bigger story, a grander story." And that story has decisively shaped how Christians have viewed the origins of their church.

Luke’s Image of Jesus

“In Luke, Jesus emerges primarily as a teacher, a teacher of ethical wisdom, someone who's confident and serene in that ethical teaching. Someone who is very much interested in inculcating the virtues of compassion and forgiveness among his followers. Professor L. Michael White told PBS: “Jesus in Luke's gospel comes across differently, he's much more like a philosophic teacher, kind of like Socrates: he's reasoned, he's dispassionate, he's a critic sometimes of society but he's certainly concerned about the way his teachings bear on society. And in the end he dies very much like Socrates. The death of Jesus in Luke's gospel is more like a martyr's death, it's much calmer, he goes inexorably to the cross, knowing that it is what must happen. Pilate isn't at fault at all. Pilate tries to get rid of the case by sending Jesus away to Herod.... Pilate isn't the enemy of Jesus, he isn't the bad guy. And once again this may reflect the kind of political concerns of Luke's gospel. Jesus also isn't a source of concern because he's not a kind of rebel figure now, rather he's a teacher, a philosopher, a social critic, a social reformer. He's a good member of the Greco-Roman world. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: “According to some interpreters, Luke's Jesus is not only a king, he also resembles a Greek philosopher. Others suggest that Luke's Jesus more closely resembles a semi-divine hero, such as those portrayed in popular stories and celebrated in Greek song. The author of Matthew wrote of a Kingdom that would embrace Jews and gentiles alike. The author of Luke wrote for a community which also awaited the arrival of God's Kingdom, but which was concerned about its life in another Kingdom, the Kingdom of Caesar. The question they faced was this: can Christians who believe in the Kingdom of God also be loyal subjects of the Roman Empire? Luke's unequivocal answer was "Yes." [Source: Marilyn Mellowes, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“The Jesus of Luke is a powerful figure. In the words of Holland Hendrix, "He comes on the scene as a prophet straight out of the Hebrew Bible. At his first appearance in his hometown, he quotes the prophet Isaiah. He comes across as a liberator, a great miracle worker. But also as the quintessential benefactor figure." Unlike Matthew's Jesus, who blesses the poor in spirit, Luke's Jesus simply blesses the poor.

“After a series of blessings addressing the peoples' physical needs, Jesus offers advice on how to live a good life: "But I say to you that listen, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and from anyone who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt. Give to everyone who begs from you; and if anyone takes away your goods, do not ask for them again. Do unto others as you would have them do to you." (LK 6:27-31).

Luke’s Message

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “One of the major concerns that the composite work of Luke and Acts addresses is whether Christians can be good citizens of the Roman Empire. After all, their founder was executed as a political criminal, and they were being associated with the destruction of Jerusalem, and some people would have thought of them as incendiaries, as revolutionaries. And Luke in his portrait wants to show that Jesus himself taught an ethic that was entirely compatible with good citizenship of the empire. And that despite the fact that one of the heroes of the Book of Acts was himself executed, namely Paul, although that was a serious mistake and had nothing to do with the political program, it wasn't in any way dangerous. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Kingdom of God

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: “The author of Matthew wrote of a Kingdom that would embrace Jews and gentiles alike. The author of Luke wrote for a community which also awaited the arrival of God's Kingdom, but which was concerned about its life in another Kingdom, the Kingdom of Caesar. The question they faced was this: can Christians who believe in the Kingdom of God also be loyal subjects of the Roman Empire? Luke's unequivocal answer was "Yes." [Source: Marilyn Mellowes, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“One of the most notable differences between Luke's gospel and those of Matthew or Mark is, in Francois Bovon's words, "its sense of joy." The gospel begins with the joyous account of Jesus' birth and ends on the victorious note of Jesus' resurrection and ascension into heaven. The sense of abandonment that characterizes Mark's ending is reduced to a brief interlude in Luke's story. As Luke's gospel ends, Jesus has departed in body. But at the beginning of Acts, his Spirit returns, guiding the disciples to the successful completion of their mission.

“Compared to the other gospels, the Jesus of Luke is less of a rabble-rouser; so, too, is the apostle Paul. This tells us something about Luke's audience: it is learning to live and to flourish in the Roman world, becoming absorbed into its surrounding society and culture. Luke wants to assure his Christian community -- and their neighbors -- that there is no conflict between faith in Jesus and loyalty to the Emperor. The kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Caesar can peacefully co-exist side by side; Christians can be good citizens of both the earthly and heavenly realms. Luke's hopes for acceptance are reflected in the way he portrays the death of Jesus. His last words are "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do." (LK23:34) The Jesus of Luke dies with calm resolution: he knows that his death will be followed by the birth of the church.

Professor L. Michael White told PBS:“One of the places we see this most clearly is in the way that Luke tells the parable of the prodigal son. It's a very familiar story. And it's a story about repentance. The younger of two brothers who runs away, squanders his inheritance living a vile life and only after he goes into the depths of depression because he has no money and doesn't know where he's going to live, he decides to go home and be just a slave in his father's house. But when he returns, his father welcomes him with open arms and says, "Let's have a great banquet to welcome you back." Now the older brother who had stayed at home all this time becomes jealous because he had been faithful to his father's wishes and desires. He had been doing what his father wanted all along. It's the younger brother who had squandered everything and gone against his father's wishes. This story is really about Luke's perception of the relation between gentiles and Jews in the household of God. It is Luke's description of the church as being willing to accept both the older brother, the faithful brother, the Jews, alongside of the prodigal son, the gentiles, who had lived a terrible life away from the father for so long but now in the church are being welcomed back with open arms. Luke's vision is of a unified humanity in the church that brings all of God's children back together. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Luke and Acts: Early Christian Romance and First Christian History

Acts

Holland Lee Hendrix told PBS: “Luke/Acts is a very interesting example of evolved early Christian literature because the author now is undertaking this work... commissioned by a benefactor. And he goes about it very, very methodically as a good Roman author would. He sets the stage historically as you would expect in some kind of sort of almost historical novel, and then he tells a perfectly wonderful story. In fact, it's such a good story that many scholars have compared it to the novelistic literature of time, and have interpreted Luke/Acts as really an early Christian romance, with all the ingredients of romance, down to shipwrecks and exotic animals and exotic vegetation, cannibalistic natives - all kinds of embellishments that one finds in the romance literature of the time. But it's done in a very historically disciplined way, or at least one that seems to be historically disciplined, by a very careful author who identifies himself as an artist under the economic sphere of a particular benefactor. So Luke/Acts does represent a very interesting stage in the evolution of early Christian literature. It's now become thoroughly Romanized. [Source: Holland Lee Hendrix, President of the Faculty Union Theological Seminary, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: ““It's also important to recognize that Luke's gospel has a companion volume. Luke is by the same author as the Book of Acts in the New Testament, the book that tells the story of the beginnings of the Christian movement and down through the time of Paul's career. And it's very clear from the way the two books open up, and the prologue to each one, that we're working with the same author and that the narrative continues from one to the next. So the author of Luke/Acts, and that's what we call them now, that's a two-volume work, the author of Luke/Acts is telling us a bigger story, a grander story, a story that starts with Jesus and is concerned with how his life played out , but then sees the story continuing with the founding of the church and with its spread and with the eventual travels of Paul that take him to Rome itself. It's a story with a much greater political self consciousness. It's a story told from the plateau of history. Indeed Luke/Acts is the first attempt to write a history of the Christian movement from the inside. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: ““It's also important to recognize that Luke's gospel has a companion volume. Luke is by the same author as the Book of Acts in the New Testament, the book that tells the story of the beginnings of the Christian movement and down through the time of Paul's career. And it's very clear from the way the two books open up, and the prologue to each one, that we're working with the same author and that the narrative continues from one to the next. So the author of Luke/Acts, and that's what we call them now, that's a two-volume work, the author of Luke/Acts is telling us a bigger story, a grander story, a story that starts with Jesus and is concerned with how his life played out , but then sees the story continuing with the founding of the church and with its spread and with the eventual travels of Paul that take him to Rome itself. It's a story with a much greater political self consciousness. It's a story told from the plateau of history. Indeed Luke/Acts is the first attempt to write a history of the Christian movement from the inside. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Jesus in Luke

Christ Carrying the Cross by El Greco

Holland Lee Hendrix told PBS: “The Jesus of Luke is an enormously powerful figure. I mean he comes on the scene as a prophet straight out of the Hebrew Bible. At his first appearance in his hometown synagogue he quotes the prophet Isaiah and it's the passage that talks about freeing those who are oppressed and letting those who are blind see. Jesus is a powerful figure and comes across as a liberator, a great miracle worker. But also, and this is interesting in view of the authorship of Luke, also as the quintessential benefactor. He is the one who dispenses the great gifts of God and God is viewed again as a great benefactor figure in Luke/Acts. So Jesus is probably at his most powerful in the gospel of Luke, from a variety of perspectives, as prophet, as healer, as savior, as benefactor. [Source: Holland Lee Hendrix, President of the Faculty Union Theological Seminary, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Professor Helmut Koester told PBS: “Luke portrays Jesus in the gospel in essentially according to the image of the divine man. The person in whom divine powers are visible and are exercised, both in his teaching and in his miracle doing. The image of the divine man also belongs in Jesus' travel narrative. The gospel of Luke is the only one that has a long travel narrative of Jesus.... The travel motif has been a very important motif in antiquity to describe the life of great divine men, miracle workers, teachers.... [Source: Helmut Koester, John H. Morison Professor of New Testament Studies and Winn Professor of Ecclesiastical History Harvard Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“The divine man motif is important even through Jesus' suffering and death, because Jesus dies the perfect martyr's death, an exemplary death. There is no crying, "my God, my God, why has Thou forsaken me?" But Jesus dies commending his spirit into the hands of the father, as a pious martyr really should do in a suffering death. So the image of Jesus is one that is fully developed out of the image of the divine human being....

Luke's Audience

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: “In contrast to either Mark or Matthew, Luke's gospel is clearly written more for a gentile audience. Luke is traditionally thought of as one of Paul's traveling companions and it's certainly the case that the author of Luke was from those Greek cities in which Paul had worked. Luke's gospel is a product of a kind of Pauline Christianity. And so it tells the story in some slightly different ways than do the other gospels. It has different interests. It has different thematic concerns. It probably also has a different political self consciousness because it's writing predominantly for gentiles in the Greek cities of Asia Minor or Greece itself. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

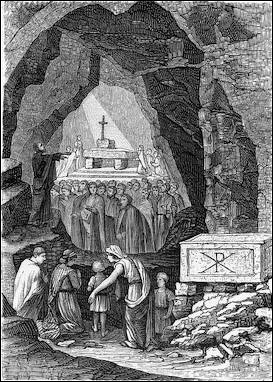

Early Christians worship in the Catacombs of Saint Calixtus

“Luke's audience seems to be a much more cultured literary kind of audience. Luke's Greek is the highest quality in style of anything in the new testament. It reads more like a novel in the Greek tradition, rather than Mark's gospel, which has a kind of crude quality at times to the Greek grammar. So anyone on the street of a Greek city picking up Luke's gospel would have felt at home with it if they were able to read good Greek....Tradition holds that Luke was actually a traveling companion of Paul. He's often called Luke the physician which means he's portrayed as a kind of educated person from the Greco-Roman world. “Now the concerns of Luke's gospel are a little different, therefore; there are political as well as social concerns that we see in the way the story is told precisely because it's writing for this much more cultured kind of audience. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Luke's audience seems to be predominantly gentile.... when they talk about the story of Jesus there's more of an emphasis on the political situation of Jesus today. Jesus is less of a rabble rouser, and so is Paul, for that matter, in these stories. And this suggests something about the situation of the audience, that they too are concerned about the way that they will be perceived, the way that the church will be perceived by the Roman authorities. It's sometimes suggested that Luke's gospel should be seen as a kind of an apologetic for the beginnings of the Christian movement, trying to make its place in the Roman world, to say, "we're okay, don't worry about us, we are just like the rest of you: we keep the peace, we're law abiding citizens, we have high moral values, we're good Romans too." ...

“Now ...the counterpart to the realization that Luke is telling the story for a Greco-Roman audience with a kind of political agenda is what happens to Luke's treatment of the Jewish tradition. Luke is much more antagonistic toward Judaism. And so the gospel of Luke and its companion volume, Acts, are also reflecting the development of the Christian movement more away from the Jewish roots and in fact ...developing more toward the Roman political and social arena. This political self consciousness and ethnic self consciousness that's being reflected by Luke/Acts is beginning to say that we, the Christians, the ones who are telling this story, are no longer in quite the same way just Jews. And so there's a growing antipathy toward at least certain elements within theJewish tradition and within Jewish society.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024