Home | Category: Neanderthals

NEANDERTHALS: DIM-WITTED BRUTES OR INTELLIGENT AS HUMANS?

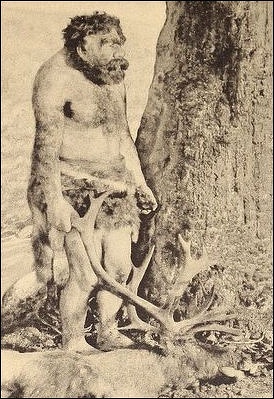

Early depiction of a Neanderthal

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: Neanderthals “have suffered a bad press since the first skeletons were unearthed in the Neander valley near Düsseldorf in the 19th century. While the German biologist Ernst Haeckel failed to convince his fellow scientists to name the species Homo stupidus, Neanderthals were still described as incapable of moral or theistic conceptions, and depicted as knuckle-dragging apemen.” [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, February 22, 2018 |=| ]

In The Neanderthal Man, a 1953 horror film, a mad scientist turns his cat into a saber-toothed tiger and himself into a prehistoric avenger of his people after being humiliated by scientists who laughed at his argument that Neanderthals were intelligent beings. For a 1955 fashion show spoofing “Formal Wear Through the Ages,” comedian Buddy Hackett and actress Gretchen Wyler dressed up like Fred and Wilma Flintstone. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, May 2019]

Neanderthals are no longer regarded as dim-witted creatures incapable of creating art or developing sophisticated tools. Recent discovers, however, have shown that Neanderthals did in fact create art and develop advanced tools as well as hunt in organized groups, care for the sick and aged and perform rituals that may have had a spiritual component. Furthermore they may have had a primitive language. "Neanderthals were highly resourceful, highly intelligent creatures," Fred Smith, a Neanderthal specialist at Illinois University, told National Geographic. "They were not big, dumb brutes by any stretch of the imagination. They were us — only different."

Christopher Stringer of the Natural History Museum of London wrote in the Times of London, “Their braincases were big, but long and low, with a large browridge instead of the domed forehead of modern humans...We cannot be certain about how intelligent they were but the Neanderthals were capable hunters, gatherers and toolmakers. While it does not seem they were great innovators, during the final 30,000 years of their existence they started to make more advanced tools, showed increasing use of pigments and developed production of jewelry."

Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science Is Rewriting Their Story”

by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse (2022) Amazon.com;

Neanderthal Religion? : Theology in Dialogue with Archaeology” by Thomas Hughson Amazon.com;

“Understanding Middle Palaeolithic Asymmetric Stone Tool Design and Use: Functional Analysis and Controlled Experiments to Assess Neanderthal” by Lisa Schunk Amazon.com;

“The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body”

by Steven Mithen (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature” by Ludovic Slimak Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

Neanderthals Just Like Us?

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: “At least on some occasions, they buried their dead. Also on some occasions, they appear to have killed and eaten each other. Wear on their incisors suggests that they spent a lot of time grasping animal skins with their teeth, which in turn suggests that they processed hides into some sort of leather. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, August 15, 2011]

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “Neanderthals weren’t the slow-witted louts we’ve imagined them to be — not just a bunch of Neanderthals. As a review of findings published last year put it, they were actually “very similar” to their contemporary Homo sapiens in Africa, in terms of “standard markers of modern cognitive and behavioral capacities.” We’ve always classified Neanderthals, technically, as human — part of the genus Homo. But it turns out they also did the stuff that, you know, makes us human. [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“Neanderthals buried their dead. They made jewelry and specialized tools. They made ocher and other pigments, perhaps to paint their faces or bodies — evidence of a “symbolically mediated worldview,” as archaeologists call it. Their tracheal anatomy suggests that they were capable of language and probably had high-pitched, raspy voices, like Julia Child. They manufactured glue from birch bark, which required heating the bark to at least 644 degrees Fahrenheit — a feat scientists find difficult to duplicate without a ceramic container. In Gibraltar, there’s evidence that Neanderthals extracted the feathers of certain birds — only dark feathers — possibly for aesthetic or ceremonial purposes. And while Neanderthals were once presumed to be crude scavengers, we now know they exploited the different terrains on which they lived. They took down dangerous game, including an extinct species of rhinoceros. Some ate seals and other marine mammals. Some ate shellfish. Some ate chamomile. (They had regional cuisines.) They used toothpicks.||*||

“Wearing feathers, eating seals — maybe none of this sounds particularly impressive. But it’s what our human ancestors were capable of back then too, and scientists have always considered such behavioral flexibility and complexity as signs of our specialness. When it came to Neanderthals, though, many researchers literally couldn’t see the evidence sitting in front of them. A lot of the new thinking about Neanderthals comes from revisiting material in museum collections, excavated decades ago, and re-examining it with new technology or simply with open minds. The real surprise of these discoveries may not be the competence of Neanderthals but how obnoxiously low our expectations for them have been — the bias with which too many scientists approached that other Us. One archaeologist called these researchers “modern human supremacists.”“ ||*||

Neanderthals Discovered in the Neander Valley

Neanderthal Valley today

The Neanderthal bones found in 1856 in the Neander Valley in Germany (“thal” is German for valley), 12 kilometers south of Dusseldorf, were the first remains ever found of a prehistoric human ancestor. The remains, found in a limestone mine, consisted of a beetle-browed, low-sloping skullcap, part of a pelvis, and thick-limbed bones. The German workers who found them in a cave thought they belonged to an extinct bear. The first Neanderthal fossil was found in Belgium in 1830 but was not identified as belonging to a Neanderthal until almost a century later.

In 1856, Darwin's Origin of Species had yet to be published and much of the Western world believed that mankind was created by God five days after the heavens and the earth in 4004 B.C.(a date calculated by an Irish theologian). After examining the Neander Valley bones an Irish geologist suggested they may have come from a human ancestor. Most people scoffed at that suggestion. They believed the bones either belonged to a Cossack deserter from the Napoleonic wars, a refugee from Noah's Ark, a village idiot, or a modern man deformed by rickets, arthritis and a blow to the head. When two more Neanderthal skeletons were discovered in Belgian cave in 1886 scientists said that it was unlikely that these men were deformed by the same set of circumstances as the man found in the Neander Valley in 1856. [Source: Michael Lemonick, Time, March 14, 1994]

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: “The first Neanderthal was found in a limestone cave about forty-five miles north of Bonn, in an area known as the Neander Valley, or, in German, das Neandertal. Although the cave is gone—the limestone was long ago quarried into building blocks—the area is now a sort of Neanderthal theme park, with its own museum, hiking trails, and a garden planted with the kinds of shrubs that would have been encountered during an ice age. In the museum, Neanderthals are portrayed as kindly, if not particularly telegenic, humans. By the entrance to the building, there’s a model of an elderly Neanderthal leaning on a stick. He is smiling benignantly and resembles an unkempt Yogi Berra. Next to him is one of the museum’s most popular attractions—a booth called the Morphing-Station. For three euros, visitors to the station can get a normal profile shot of themselves and, facing that, a second shot that has been doctored. In the second, the chin recedes, the forehead slopes, and the back of the head bulges out. Kids love to see themselves—or, better yet, their siblings—morphed into Neanderthals. They find it screamingly funny. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, August 15, 2011]

“When the first Neanderthal bones showed up in the Neander Valley, they were treated as rubbish (and almost certainly damaged in the process). The fragments—a skullcap, four arm bones, two thighbones, and part of a pelvis—were later salvaged by a local businessman, who, thinking they belonged to a cave bear, passed them on to a fossil collector. The fossil collector realized that he was dealing with something much stranger than a bear. He declared the remains to be traces of a “primitive member of our race.”

“As it happened, this was right around the time that Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” and the fragments soon got caught up in the debate over the origin of humans. Opponents of evolution insisted that they belonged to an ordinary person. One theory held that it was a Cossack who had wandered into the region in the tumult following the Napoleonic Wars. The reason the bones looked odd—Neanderthal femurs are distinctly bowed—was that the Cossack had spent too long on his horse. Another attributed the remains to a man with rickets: the man had been in so much pain from his disease that he’d kept his forehead perpetually tensed—hence the protruding brow ridge. (What a man with rickets and in constant pain was doing climbing into a cave was never really explained.)”

See Separate Article: FAMOUS NEANDERTHAL SITES europe.factsanddetails.com

Discovery of Early Neanderthal Skeletons

Spy Cave in 1886

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: “Over the next decades, bones resembling those from the Neander Valley—thicker than those of modern humans, with strangely shaped skulls—were discovered at several more sites, including two in Belgium and one in France. Meanwhile, a skull that had been unearthed years earlier in Gibraltar was shown to look much like the one from Germany. Clearly, all these remains could not be explained by stories of disoriented Cossacks or rachitic spelunkers. But evolutionists, too, were perplexed by them. Neanderthals had very large skulls—larger, on average, than people today. This made it hard to fit them into an account of evolution that started with small-brained apes and led, through progressively bigger brains, up to humans. In “The Descent of Man,” which appeared in 1871, Darwin mentioned Neanderthals only in passing. “It must be admitted that some skulls of very high antiquity, such as the famous one of Neanderthal, are well developed and capacious,” he noted. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, August 15, 2011]

“In 1908, a nearly complete Neanderthal skeleton was discovered in a cave near La Chapelle-aux-Saints, in southern France. The skeleton was sent to a paleontologist named Marcellin Boule, at Paris’s National Museum of Natural History. In a series of monographs, Boule invented what might be called the cartoon version of the Neanderthals—bent-kneed, hunched over, and brutish. Neanderthal bones, Boule wrote, displayed a “distinctly simian arrangement,” while the shape of their skulls indicated “the predominance of functions of a purely vegetative or bestial kind.” Boule’s conclusions were studied and then echoed by many of his contemporaries; the British anthropologist Sir Grafton Elliot Smith, for instance, described Neanderthals as walking with “a half-stooping slouch” upon “legs of a peculiarly ungraceful form.” (Smith also claimed that Neanderthals’ “unattractiveness” was “further emphasized by a shaggy covering of hair over most of the body,” although there was—and still is—no clear evidence that they were hairy.)

“In the nineteen-fifties, a pair of anatomists, Williams Straus and Alexander Cave, decided to reëxamine the skeleton from La Chapelle. What Boule had taken for the Neanderthal’s natural posture, Straus and Cave determined, was probably a function of arthritis. Neanderthals did not walk with a slouch, or with bent knees. Indeed, given a shave and a new suit, the pair wrote, a Neanderthal probably would attract no more attention on a New York City subway “than some of its other denizens.” More recent scholarship has tended to support the idea that Neanderthals, if not quite up to negotiating the I.R.T., certainly walked upright, with a gait we would recognize more or less as our own. The version of Neanderthals offered by the Neanderthal Museum—another cartoon—is imbued with cheerful dignity. Neanderthals are presented as living in tepees, wearing what look like leather yoga pants, and gazing contemplatively over the frozen landscape. “Neanderthal man was not some prehistoric Rambo,” one of the display tags admonishes. “He was an intelligent individual.”

Shaping of the Idea That Neanderthals Were Dimwits

Neanerthal depiction from 1929

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “Joachim Neander was a 17th-century Calvinist theologian who often hiked through a valley outside Düsseldorf, Germany, writing hymns. Neander understood everything around him as a manifestation of the Lord’s will and work. There was no room in his worldview for randomness, only purpose and praise. “See how God this rolling globe/swathes with beauty as a robe,” one of his verses goes. “Forests, fields, and living things/each its Master’s glory sings.” He wrote dozens of hymns like this — awe-struck and simple-minded. Then he caught tuberculosis and died at 30. [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“Almost two centuries later, in the summer of 1856, workers quarrying limestone in that valley dug up an unusual skull. It was elongated and almost chinless, and the fossilized bones found alongside it were extra thick and fit together oddly. This was three years before Darwin published “The Origin of Species.” The science of human origins was not a science; the assumption was that our ancestors had always looked like us, all the way back to Adam. (Even distinguishing fossils from ordinary rock was beyond the grasp of many scientists. One popular method involved licking them; if the material had animal matter in it, it stuck to your tongue.) And so, as anomalous as these German bones seemed, most scholars had no trouble finding satisfying explanations. A leading theory held that this was the skeleton of a lost, bowlegged Cossack with rickets. The peculiar bony ridge over the man’s eyes was a result of the poor Cossack’s perpetually furrowing his brow in pain — because of the rickets. ||*||

“One British geologist, William King, suspected something more radical. Instead of being the remains of an atypical human, they might have belonged to a typical member of an alternate humanity. In 1864, he published a paper introducing it as such — an extinct human species, the first ever discovered. King named this species after the valley where it was found, which itself had been named for the ecstatic poet who once wandered it. He called it Homo neanderthalensis: Neanderthal Man. ||*||

“Who was Neanderthal Man? King felt obligated to describe him. But with no established techniques for interpreting archaeological material like the skull, he fell back on racism and phrenology. He focused on the peculiarities of the Neanderthal’s skull, including the “enormously projecting brow.” No living humans had skeletal features remotely like these, but King was under the impression that the skulls of contemporary African and Australian aboriginals resembled the Neanderthals’ more than “ordinary” white-people skulls. So extrapolating from his low opinion of what he called these “savage” races, he explained that the Neanderthal’s skull alone was proof of its moral “darkness” and stupidity. “The thoughts and desires which once dwelt within it never soared beyond those of a brute,” he wrote. Other scientists piled on. So did the popular press. We knew almost nothing about Neanderthals, but already we assumed they were ogres and losers. ||*||

“The genesis of this idea, the historian Paige Madison notes, largely comes down to flukes of “timing and luck.” While King was working, another British scientist, George Busk, had the same suspicions about the Neander skull. He had received a comparable one, too, from the tiny British territory of Gibraltar. The Gibraltar skull was dug up long before the Neander Valley specimen surfaced, but local hobbyists simply labeled it “human skull” and forgot about it for the next 16 years. Its brow ridge wasn’t as prominent as the Neander skull’s, and its features were less imposing; it was a woman’s skull, it turns out. Busk dashed off a quick report but stopped short of naming the new creature. He hoped to study additional fossils and learn more. Privately, he considered calling it Homo calpicus, or Gibraltar Man. |So, what if Busk — “a conscientious naturalist too cautious to make premature claims,” as Madison describes him — had beaten King to publication? Consider how different our first impressions of a Gibraltar Woman might have been from those of Neanderthal Man: what feelings of sympathy, or even kinship, this other skull might have stirred. “||*||

Marcellin Boule and Out Misconceptions About Neanderthals

Marcellin Boule

Our image of Neanderthals as "dim-witted brutes" originally came from Marcellin Boule, a French authority on fossils who reconstructed a near complete skeleton found in southwestern France, and claimed it had "prehensile feet, could not fully extend his legs, and thrust his head awkwardly forward because his spine prevented him from standing upright." In his scientific paper he described the "brutish appearance of this muscular and clumsy body."

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “One of the earliest authorities on Neanderthals was a Frenchman named Marcellin Boule. A lot of what he said was wrong. In 1911, Boule began publishing his analysis of the first nearly complete Neanderthal skeleton ever discovered, which he named Old Man of La Chapelle, after the limestone cave where it was found. Laboring to reconstruct the Old Man’s anatomy, he deduced that its head must have been slouched forward, its spine hunched and its toes spread like an ape’s. Then, having reassembled the Neanderthal this way, Boule insulted it. This “brutish” and “clumsy” posture, he wrote, clearly indicated a lack of morals and a lifestyle dominated by “functions of a purely vegetative or bestial kind.” A colleague of Boule’s went further, claiming that Neanderthals usually walked on all fours and never laughed: “Man-ape had no smile.” Boule was part of a movement trying to reconcile natural selection with religion; by portraying Neanderthals as closer to animals than to us, he could protect the ideal of a separate, immaculate human lineage. When he consulted with an artist to make a rendering of the Neanderthal, it came out looking like a furry, mean gorilla. [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“Neanderthal fossils kept surfacing in Europe, and scholars like Boule were scrambling to make sense of them, improvising what would later grow into a new interdisciplinary field, now known as paleoanthropology. The evolution of that science was haphazard and often comically unscientific. An exhaustive history by Erik Trinkaus and Pat Shipman describes how Neanderthals became “mirrors that reflected, in all their awfulness and awesomeness, the nature and humanity of those who touched them.” That included a lot of human blundering. It became clear only in 1957, for example — 46 years after Boule, and after several re-examinations of the Old Man’s skeleton — that Boule’s particular Neanderthal, which led him to imagine all Neanderthals as stooped-over oafs, actually just had several deforming injuries and severe osteoarthritis. ||*||

“Still, Boule’s influence was long-lasting. Over the years, his ideologically tainted image of Neanderthals was often refracted through the lens of other ideologies, occasionally racist ones. In 1930, the prominent British anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith, writing in The New York Times, channeled Boule’s work to justify colonialism. For Keith, the replacement of an ancient, inferior species like Neanderthals by newer, heartier Homo sapiens proved that Britain’s actions in Australia — “The white man ... replacing the most ancient type of brown man known to us” — was part of a natural order that had been operating for millenniums.” ||*||

Understanding Why Neanderthals Got a Bad Rap

Boule Human and Neanderthal depictions from 1912

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “It’s easy to get snooty about all this unenlightened paleoanthropology of the past. But all sciences operate by trying to fit new data into existing theories. And this particular science, for which the “data” has always consisted of scant and somewhat inscrutable bits of rock and fossil, often has to lean on those meta-narratives even more heavily. “Assumptions, theories, expectations,” the University of Barcelona archaeologist João Zilhão says, “all must come into play a lot, because you are interpreting data that do not speak for themselves.” [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“Imagine, for example, working in a cave without any skulls or other easily distinguishable fossils and trying to figure out if you’re looking at a Neanderthal settlement or a more recent, modern human one. In the past, scientists might turn to the surrounding artifacts, interpreting more primitive-looking tools as evidence of Neanderthals and more advanced-looking tools as evidence of early modern humans. But working that way, it’s easy to miss evidence of Neanderthals’ resemblance to us, because, as soon as you see it, you assume they were us. So many techniques similarly hinge on interpretation and judgment, even perfectly empirical-sounding ones, like “morphometric analysis” — identifying fossils as belonging to one species rather than another by comparing particular parts of their anatomy — and radiocarbon dating. How the material to be dated is sampled and how results are calibrated are susceptible to drastic revision and bitter disagreement. (What’s more, because of an infuriating quirk of physics, the effectiveness of radiocarbon dating happens to break down around 40,000 years ago — right around the time of the Neanderthal extinction. One of our best tools for looking into the past becomes unreliable at exactly the moment we’re most interested in examining.) ||*||

“Ultimately, a bottomless relativism can creep in: tenuous interpretations held up by webs of other interpretations, each strung from still more interpretations. Almost every archaeologist I interviewed complained that the field has become “overinterpreted” — that the ratio of physical evidence to speculation about that evidence is out of whack. Good stories can generate their own momentum. ||*||

“Starting in the 1920s, older and more exciting hominin fossils, like Homo erectus, began surfacing in Africa and Asia, and the field soon shifted its focus there. The Washington University anthropologist Erik Trinkaus, who began his career in the early ’70s, told me, “When I started working on Neanderthals, nobody really cared about them.” The liveliest question about Neanderthals was still the first one: Were they our direct ancestors or the endpoint of a separate evolutionary track? Scientists called this question “the Neanderthal Problem.” Some of the theories worked up to answer it encouraged different visions of Neanderthal intelligence and behavior. The “Multiregional Model,” for example, which had us descending from Neanderthals, was more inclined to see them as capable, sympathetic and fundamentally human; the opposing “Out of Africa” hypothesis, which held that we moved in and replaced them, cast them as comparatively inferior.” ||*||

Neanderthals: Modern Humans with an Iodine Deficiency?

Jerome Dobson, a geographer at Tennessee's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, has suggested that Neanderthals were nothing more than modern men with an iodine deficiency. Endemic iodine deficiency might also explain why the Neanderthals disappeared from the fossil record so suddenly.

Dobson based his theory on the similarity of the physical features of cretins (modern men with an iodine deficiency) and Neanderthals: large heads, ridged eyebrows, thick bones and muscles and degenerative joint diseases. He also points that many Neanderthal sites are in the "goiter belts" of central and Alpine, where goiter (another iodine deficiency disease) and cretinism were common until the iodonized salt was introduced in the 20th century.

The famous Venus statues bear other physical features associated with cretinism: protruding bellies, large, sagging breasts, short trunks, curved spine and short stubby fingers. Critics of Dobson's work point out that some Neanderthal sites are near the sea, where people usually get enough iodine from fish and other sea creatures, and some physical traits of cretinism are not found in Neanderthals.

Making a Case for Advanced Neanderthals

Some anthropologists have proposed that Neanderthals became extinct because their cognitive abilities were inferior, including a lack of long-term planning. But the archaeological record shows Neanderthals drove herds of big game animals into dead-end ravines and ambushed them, as evidenced by repeatedly used kill sites -- a sign of long-term planning and coordination among hunters. [Source: University of Colorado Boulder, March 14, 2011]

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “For decades, when evidence of a more advanced Neanderthal way of life turned up, it was often explained away, or mobbed by enough contrary or undermining interpretations that, over time, it never found real purchase. Some findings broke through more than others, however, like the discovery of what was essentially a small Neanderthal cemetery, in Shanidar Cave, in what is now Iraqi Kurdistan. There had been many compelling instances of Neanderthals’ burying their dead, but Shanidar was harder to ignore, especially after soil samples revealed the presence of huge amounts of pollen. This was interpreted as the remains of a funerary floral arrangement. An archaeologist at the center of this work, Ralph Solecki, published a book called “Shanidar: The First Flower People.” It was 1971 — the Age of Aquarius. Those flowers, he’d go on to write, proved that Neanderthals “had ‘soul.’?” [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“Then again, Solecki’s idea was eventually discredited. In 1999, a more thorough analysis of the Shanidar grave site found that Neanderthals almost certainly did not leave flowers there. The pollen had been tracked in, thousands of years later, by burrowing, gerbil-like rodents. (That said, even a half-century later, there are still paleoanthropologists at work on this question. It might not have been gerbils; it may have been bees.) ||*||

“As more supposed anomalies surfaced, they became harder to brush off. In 1996, the paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin and others used CT scanning technology to re-examine a bone fragment found in a French cave decades earlier, alongside a raft of advanced tools and artifacts, associated with the so-called Châtelperronian industry, which archaeologists always presumed was the work of early modern humans. Now Hublin’s analysis identified the bone as belonging to a Neanderthal. But rather than reascribe the Châtelperronian industry to Neanderthals, Hublin chalked up his findings to “acculturation”: Surely the Neanderthals must have learned how to make this stuff by watching us. ||*||

““To me,” says Zilhão, the University of Barcelona archaeologist, “there was a logical shock: If the paradigm forces you to say something like this, there must be something wrong with the paradigm.” Zilhão published a stinging critique challenging the field to shake off its “anti-Neanderthal prejudice.” Papers were fired back and forth, igniting what Zilhão calls “a 20-year war” and counting. Then, in the middle of that war, geneticists shook up the paradigm completely.” ||*||

Breakthrough: Sequencing Neanderthal DNA

60,000-Year-Old Neanderthal flute

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “A group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, led by Svante Paabo, had been assembling a draft sequence of a Neanderthal genome, using DNA recovered from bones. Their findings were published in 2010. It had already become clear by then that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals appeared in Eurasia separately — “Out of Africa was essentially right” — but Paabo’s work revealed that before the Neanderthals disappeared, the two groups mated. Even today, 40,000 years after our gene pools stopped mixing, most living humans still carry Neanderthal DNA, making up roughly 1 to 2 percent of our total genomes. The data shows that we also apparently bred with other hominins, like the Denisovans, about which very little is known. [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“It was staggering; even Paabo couldn’t bring himself to believe it at first. But the results were the results, and they carried a sort of empirical magnetism that archaeological evidence lacks. “Geneticists are much more powerful, numerous and incomparably better funded than anyone else dealing with this stuff,” Zilhão said. He joked: “Their aura is kind of miraculous. It’s a bit like receiving the Ten Commandments from God.” Paabo’s work, and a continuing wave of genomic research, has provided clarity but also complexity, recasting our oppositional, zero-sum relationship into something more communal and collaborative — and perhaps not just on the genetic level. The extent of the interbreeding supported previous speculation, by a minority of paleoanthropologists, that there might have been cases of Neanderthals and modern humans living alongside each other, intermeshed, for centuries, and that generations of their offspring had found places in those communities, too. Then again, it’s also possible that some of the interbreeding was forced. ||*||

“Paabo now recommends against imagining separate species of human evolution altogether: not an Us and a Them, but one enormous “metapopulation” composed of shifting clusters of essentially human-ish things that periodically coincided in time and space and, when they happened to bump into one another, occasionally had sex. ||*||

Archaeological Work in Gorham’s Cave

Neanderthal engraving from Gorham's Cave

Describing the archaeological work in Gorham’s Cave, Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “Every summer, since 1989, a team of archaeologists has returned to meticulously clear that sand away and recover the material inside....Inside Gorham’s Cave, archaeologists were excavating what they called a hearth — not a physical fireplace but a spot in the sand where, around 50,000 years ago, Neanderthals lit a fire. Each summer, the Gibraltar Museum employs students from universities in England and Spain to work the dig, and now two young women — one from each country — sat cross-legged under work lights, clearing sand away with the edge of a trowel and a brush to leave a free-standing cube. A black band of charcoal ran through it. [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“The students worked scrupulously, watching for small animal bones or artifacts. They’d pulled out a butchered ibex mandible, a number of mollusk shells and pine-nut husks. They’d also found six chunks of fossilized hyena dung, as well as “débitage,” distinctive shards of flint left over when Neanderthals shattered larger pieces to make axes. ||*||

“The cube of sand would eventually be wrapped in plaster and sent for analysis. The sand the two women were sweeping into their dustpans was transferred into plastic bags and marched out of the cave, down to the beach, where other students sieved it. Smaller bones caught in the sieve were bagged and labeled. Even the sand that passed through the sieve was saved and driven back to a lab at the museum, where I would later find three other students picking through it with magnifying glasses and tweezers, searching for tinier stuff — rodent teeth, sea-urchin spines — while listening to “Call Me Maybe.” ||*||

“To an outsider, it looked preposterous. The archaeologists were cataloging and storing absolutely everything, treating this physical material as though it were digital information — JPEGs of itself. And yet they couldn’t afford not to: Everything a Neanderthal came into contact with was a valuable clue. (In 28 years of excavations here, archaeologists have yet to find a fossil of an actual Neanderthal.) “This is like putting together a 5,000-piece jigsaw puzzle where you only have five pieces,” Clive Finlayson of the Gibralter Museum said. He somehow made this analogy sound exciting instead of hopeless.” ||*||

What Archaeological Can Tell Us About Neanderthals

Jon Mooallemjan wrote in the New York Times magazine: “By that point, the enormousness of what they didn’t know — what they could never know — had become a distraction for me. One of the dig’s lead archaeologists, Richard Jennings of Liverpool John Moores University, listed the many items they had found around that hearth. “And this is literally just from two squares!” he said. (A “square,” in archaeology, is one meter by one meter; sites are divided into grids of squares.) Then Jennings waved wordlessly at the rest of the sand-filled cave. Look at the big picture, he was saying; imagine what else we’ll find! There was also Vanguard Cave next door, an even more promising site, because while Gorham’s had been partly excavated by less meticulous scientists in the 1940s and ’50s, Finlayson’s team was the first to touch Vanguard. Already they had uncovered a layer of perfectly preserved mud there. (“We suspect, if there’s a place where you’re going to find the first Neanderthal footprint, it will be here,” Finlayson said.) The “resolution” of the caves was incredible; the wind blew sand in so fast that it preserved short periods, faithfully, like entries in a diary. Finlayson has described it as “the longest and most detailed record of [Neanderthals’] way of life that is currently available.” [Source: Jon Mooallemjan, New York Times magazine, January 11, 2017 ||*||]

“This was the good news. And yet there were more than 20 other nearby caves that the Gibraltar Neanderthals might have used, and they were now underwater, behind us. When sea levels rose around 20,000 years ago, the Mediterranean drowned them. It also drowned the wooded savanna between Gorham’s and the former coastline — where, presumably, the Neanderthals had spent an even larger share of their lives and left even more artifacts. ||*||

“So yes, Jennings was right: There was a lot of cave left to dig through. But it was like looking for needles in a haystack, and the entire haystack was merely the one needle they had managed to find in an astronomically larger haystack. And most of that haystack was now inaccessible forever. I could tell it wasn’t productive to dwell on the problem at this scale, while picking pine-nut husks from the hearth, but there it was. ||*||

Neanderthal art that predates human art

““Look, you can almost see what’s happening,” Finlayson eventually said. “The fire and the charcoal, the embers scattering.” It was true. If you followed that stratum of sand away from the hearth, you could see, embedded in the wall behind us, black flecks where the smoke and cinders from this fire had blown. Suddenly, it struck me — though it should have earlier — that what we were looking at were the remnants of a single event: a specific fire, on a specific night, made by specific Neanderthals. Maybe this won’t sound that profound, but it snapped that prehistoric abstraction into focus. This wasn’t just a “hearth,” I realized; it was a campfire. ||*||

“Finlayson began narrating the scene for me. A few Neanderthals cooked the ibex they had hunted and the mussels and nuts they had foraged and then, after dinner, made some tools around the fire. After they went to sleep and the fire died out, a hyena slinked in to scavenge scraps from the ashes and took a poop. Then — perhaps that same night — the wind picked up and covered everything with the fine layer of sand that these students were now brushing away. While we stood talking, one of the women uncovered a small flint ax, called a Levallois flake. After 50,000 years, the edge was still sharp. They let me touch it.” ||*||

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024