Home | Category: The Gospels and Early Christian Texts

GOSPELS

Luke in a Byzantine text from AD 1020 The Gospels are the most important part of the News Testament. Based on oral traditions, they are four accounts of Jesus’s life and teaching written by four evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The Gospels differ in some details but are the same on essentials. For example all the Gospels tell the story of Jesus’s death and resurrection but each tells it in a different way with a different viewpoint and a different message.

In his book “What the Gospels Meant”, the writer and thinker Gary Wills wrote the Gospels are “a mediation on the meaning of Jesus in the light of sacred history as recorded in sacred writings.” Gospels means "Good News," and is derived from the Old English "godspell." The good news was the coming Christ and his offer of salvation. The earliest New Testament writings are the letters of Paul written between A.D. 50 and 62.

Few old examples of the Gospels exist in part because of the massive destruction of Christian materials ordered by the Roman Emperor Diocletian in A.D. 303. A rare example of a pre-Diocletian manuscript was found at the Fayyum oasis in Egypt. The earliest Christian Bibles, all in Greek, date to 4th and 5th century. Most are from fragments kept at St. Catharine’s in the Sinai or were found elsewhere in Egypt.

Reverend Dr Richard Burridge, Dean of King's College London said: “The Gospels are a form of ancient biography and are very short. They take about an hour and a half, two hours to read out loud. They're not what we understand modern biography to be: the great life and times of somebody in multi volume works. They've got between ten and twenty thousand words and ancient biography doesn't waste time on great background details about where the person went to school or all the psychological upbringing that we now look for in our kind of post-Freudian age. [Source: Reverend Dr Richard Burridge, Dean of King's College London and Lecturer in New Testament Studies, September 17, 2009 |::|]

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Bible: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rose Guide to the Gospels: Side-by-Side Charts” Amazon.com ;

“What the Gospels Meant” by Garry Wills Amazon.com ;

“Why Four Gospels?” by A. W. Pink Amazon.com ;

"New Testament with Psalms and Proverbs", Pocket-Sized (New International Version, NIV,version) , Amazon.com ;

“A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New” by G. K. Beale Amazon.com ;

“Johnny Cash Reading the Complete New Testament” Amazon.com ;

“The New Testament in Its World: An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians” by N. T. Wright and Michael F. Bird Amazon.com ;

“King James Version Bible”, Black Leather-Look (imitation leather) Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Bible in English easy to read version” Amazon.com ;

“Eerdman's Dictionary of the Bible” by David Noel Eerdman Amazon.com ;

“How to Read the Bible” by James Kugel Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Bible: The Story of the World's Most Influential Book”

by John Barton, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Who Wrote the Bible?” by Richard Friedman, Julian Smith, et al.

Amazon.com ;

“The Complete Guide to the Bible” by Stephen M. Miller Amazon.com ;

“Oxford History of the Biblical World” by Michael D. Coogan Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce Metzger and Michael D. Coogan Amazon.com

Understanding the Gospels

The Gospels are collections of oral traditions. When they were written most people couldn’t read. They are believed to have initially served as guides for preachers — that were more like notes than texts that preachers were free to embellish. It is thought that quotes ascribed to Jesus were summaries of what he probably said rather than verbatim quotes. It seems plausible that Jesus really said them based on the similarities between the Gospels and the overall consistency of the message.

According to the BBC: “The Gospels were written to present the life and teachings of Jesus in ways that would be appropriate to different readerships, and for that reason are not all the same. They were not intended to be biographies of Jesus, but selective accounts that would demonstrate his significance for different cultures. The writer of Luke also wrote the Acts of the Apostles, which tells the story of how Christianity spread from being a small group of Jewish believers in the time of Jesus to becoming a worldwide faith in less than a generation. [Source: John Drane, July 12, 2011 BBC |::|]

Mark from the Four Gospels (1495)

The Gospels were not historical documents or short biographies as have been claimed but rather are articles of faith and likely works of propaganda. Historians regard them as unreliable because they were written 35 years to 60 years after the death of Jesus and they were written as proclamations (not objective history) and as polemics for a certain sect (Christianity) and a time when this sect was in competition with other sects.

Reverend Dr Richard Burridge, Dean of King's College London said: “They tend to go straight to the person's arrival on the public scene, often 20 or 30 years into their lives, and then look at the two or three big key things that they did or the big two or three key ideas. They'll also spend quite a lot of time concentrating on the actual death because the ancients believe that you couldn't sum up a person's life until you saw how they died. In their death, very often, they would die as they lived and then they would conclude with the events after the death - very often on dreams or visions about the person and what happened to their ideas afterwards. [Source: Reverend Dr Richard Burridge, Dean of King's College London and Lecturer in New Testament Studies, September 17, 2009 |::|]

“The four gospels are four angles on one person and in the four gospels there are four angles on the one Jesus. It was a wonderful insight of the early Fathers, guided by the spirit of God, who recognised that these four pictures all reflect upon the same person. It's like walking into a portrait gallery and seeing four portraits, say, of Winston Churchill: the statesman or the war leader or the Prime Minister or the painter or the family man. |::|

“Of course we actually have to do all sorts of historical critical analysis and try to get back to what this tells us about the historical Jesus. It also shows us the way in which the early church tried to make that one Jesus relevant and to apply him to the needs of their own people of that day, whether they were Jews as in Matthew's case or Gentiles as in Luke's case and so on. And so those four portraits give us a challenge and a stimulus today to actually try to work out how we can actually tell that story of the one Jesus in different ways that are relevant for the needs of people today. |::|

Synoptic Gospels and John

John in an Armenian Gospel manuscript

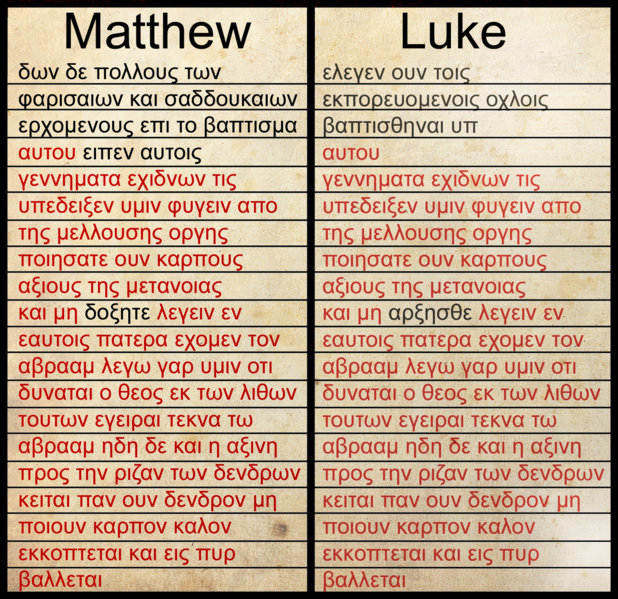

The first three Gospels are effectively different editions of the same materials, and for that reason are known as the 'synoptic gospels'. Charlotte Allen wrote: “Anyone who has ever studied the four canonical Gospels is aware that three of them -- Matthew, Mark, and Luke -- have a good deal of substantive material and even exact wording in common. (The fourth Gospel, John, although it contains a few parallels with the other three, is largely idiosyncratic in its subject matter and its presentation of Jesus.) For that reason Matthew, Mark, and Luke are called the Synoptic Gospels ("synoptic" derives from a Greek verb meaning "to see together"). [Source: , The Atlantic, December 1996 ~]

About 90 percent of Mark's subject matter is also in Matthew, and more than 50 percent of Mark's subject matter is in Luke. Matthew and Luke are both a good deal longer than Mark, however: they each contain around 1,100 verses, whereas Mark contains 661. Furthermore, both Matthew and Luke frequently follow Mark's order when presenting Mark's material, though they seldom put the other material they have in common into the same place in Mark's framework. That material appears in scattered chunks in Luke, whereas in Matthew it is organized rhetorically around a theme, such as the Sermon on the Mount. ~

“Finally, studying the Greek texts of the three Synoptics side by side suggests that the relationship among them may be literary, a matter of their authors' having read one another's work rather than having drawn on the same eyewitness accounts or a common oral tradition about Jesus. In many cases the three evangelists used the exact same Greek word, right down to the verb form, in a narration of the same event. In a few cases entire sentences are almost identical among the three. The matter shared by all three Synoptics is known in New Testament circles as the triple tradition. The matter shared by only Matthew and Luke -- amounting to about one fifth of the verses in each evangelist's Gospel -- is known as the double tradition.: ~

Gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke and John

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke are very similar and in some cases have the exact same wording. They are often called the Sypnotic Gospels ("sypnotic" is derived from a Greek word for "to see together"). About 90 percent of the material in Mark is also in Matthew and 50 percent of what is in Luke is also in Matthew. Mark and Luke are considerably longer than Matthew. They have about 1,100 verses compared to Matthew's 610.

Matthew miniature in the Peresopnytske Gospel

The Gospel of Mark is the oldest, shortest, clearest and believed to be the most historically accurate of the Gospels. It has few references to the divinity of Jesus and originally had nothing about the Resurrection. It was reportedly written between A.D. 67 and 70 and has more details and a rougher style than the other Gospels. Mark was a disciple of Jesus and was associated with Peter. Wills called his work a “report from the suffering body of Christ” written to comfort early Christians facing persecution.

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke and Acts were reportedly written in A.D. 85. Matthew was a Jewish tax collector and one of the 12 disciples. He is thought to have lived in a Jewish community in either Galilee or what is now Lebanon. It is not clear whether he was really the author of his Gospel. In any case his Gospel is sometimes referred to as the teaching Gospel as it recounts many familiar sermons. Luke was “the beloved physician” and a companion of St. Paul. He is thought to have originally been a pagan rather than a Jew, who wrote in Greek and used more dramatic touches like those found in Greek myths. He was probably the author of his Gospel and the Acts. His Gospel has been described “the reconciling body of Christ.” It contains famous stories like Prodigal Son and the Good Samaritan, expressing the humanity of Jesus and the universality of his message.

The Gospel of John was reportedly written in A.D. 90 to 95. It is believed to have been written particularly for churches in the area of Ephesus in Asia Minor. Some think that John was the “disciple that Jesus loved.” Scholars sometimes refer to the Gospel of John as the Forth Gospel and regard it as the most poetic and highly developed text in the New Testament. It goes beyond the life of Christ and helps frame and define Christianity itself

What the Gospels Tell Us

Marilyn Mellowes wrote: ““Each of the four gospels depicts Jesus in a different way. These characterizations reflect the past experiences and the particular circumstances of their authors' communities. The historical evidence suggests that Mark wrote for a community deeply affected by the failure of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome. Matthew wrote for a Jewish community in conflict with the Pharisaic Judaism that dominated Jewish life in the postwar period. Luke wrote for a predominately Gentile audience eager to demonstrate that Christian beliefs in no way conflicted with their ability to serve as a good citizen of the Empire. Despite these differences, all four gospels contain the "passion narrative," the central story of Jesus' suffering and death. That story is directly connected to the Christian ritual of the Eucharist. As Helmut Koester has observed, the ritual cannot "live" without the story. [Source: Marilyn Mellowes Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“While the gospels tell a story about Jesus, they also reflect the growing tensions between Christians and Jews. By the time Luke composed his work, tension was breaking into open hostility. By the time John was written, the conflict had become an open rift, reflected in the vituperative invective of the evangelist's language. In the words of Prof. Eric Meyers, "Most of the gospels reflect a period of disagreement, of theological disagreement. And the New Testament tells a story of a broken relationship, and that's part of the sad story that evolves between Jews and Christians, because it is a story that has such awful repercussions in later times."

Gospels and Historical Jesus

Christ heals uncovering the roof, Mark 2:4

Kristin Romey wrote in National Geographic: “By far the most important—and possibly most debated—of those traces are the texts of the New Testament, especially the first four books: the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. But how do those ancient texts, written in the second half of the first century, and the traditions they inspired, relate to the work of an archaeologist? “Tradition gives more life to archaeology, and archaeology gives more life to tradition,” Father Alliata replies. “Sometimes they go together well, sometimes not,” he pauses, offering a small smile, “which is more interesting.” [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, November 28, 2017 ^|^]

According to the BBC: “Many Bible scholars would say that the Gospels are not primarily a historical record of what happened because: 1) they were written between 40 and 70 years after the death of Jesus: 2) those who wrote them were not present at the events they described - but the oral tradition was very strong in those days, so it was possible for information to be passed on quite accurately from actual eyewitnesses; 3) the oral tradition allowed the narrative to be reshaped as it was passed on, in order to suit the purposes of the person telling the story; 4) the Gospels differ on some of the events; 5) the purpose of the Gospels is not to provide an accurate record of the historical events of Christ's last days but to record the spiritual truth of Jesus Christ; 6) The Gospels are a combination of historical fact with theological reflection on the meaning and purpose of Christ's life and death. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “I think we're, in some ways, forced to engage in a historical critical study of scripture by the problems of scripture itself. That is, the discrepancies that we see in scripture that make it difficult for us to construct a simple and coherent historical narrative out of the data of the text, which after all, are faith statements and calls to belief in Christ. At the same time, I think we're encouraged to engage in this kind of historical critical study because it enriches our understanding of the world within which Jesus operated, within which scriptural figures in general operated and with which they were interacting. We can't, for instance, understand what it means to proclaim the kingdom or reign of God unless we understand it was that proclamation was made in the context of an imperial power that had certain implications for human existence. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“I think too, by a historical, critical understanding of scripture we can both enrich our own appropriation of the teachings of scripture and also sort through some problematic elements in scripture. And I think unless we adopt a historical critical attitude toward our Biblical tradition we may miss appropriate scripture. For instance, if we apply too readily or accept without some sort of critical perspective some of the controversial statements within the gospel tradition about the Jews, I think we're being unfaithful to our Biblical tradition. But in order to understand those we have to put them into some sort of historical context. So we're invited to engage in historical critical study by the problems of scripture itself, encouraged to do so by the payoff of such study for understanding and enriching our appropriation of scriptural material, and I think absolutely forced to do so by the problematic elements of scripture which can only be understood within the historical context.

Gospels: A Mix of Facts and Stories?

Matt Andrews wrote in Midwest Today, “Most experts take the moderate position that the canonical gospels are neither the second-century tissue of fabrications nor quite the contemporary eyewitness accounts that, given the nature of Christianity's claims, it would be reasonable to expect. Ironically, it has not been theologians but outsiders, such as students of ancient history, well accustomed to imperfections in the works of the pagan writers of antiquity, who have been prepared to recognize the strong vein of authenticity underlying the gospels. [Source: Matt Andrews, Midwest Today, March 1994 ^=^]

“Oxford English don C.S. Lewis, speaking on the subject, commented, "I have been reading poems, romances, vision literature, legends, myths all my life. I know what they are like. I know that none of them is like this. Of the text there are only two possible views. Either this is reportage - though it may no doubt contain errors - pretty close to the facts... Or else, some unknown writer in the second century, without known predecessors or successors, suddenly anticipated the whole technique of modern novelistic, realistic narrative. If it is untrue, it must be narrative of that kind. The reader who doesn't see this simply has not learned to read." ^=^

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: “From a historical perspective what we really know about the life of Jesus is very, very limited depending on which gospel you read. His actual career may be something less then one year and maybe even as little as only a few months, whereas in John's Gospel his career is nearly three years long. So there are these kinds of historical discrepancies among the gospels themselves. They range from the way his birth occurred to the actual day on which he was executed and even to the kinds of teachings and miracles that he performs throughout his career. As a result we begin to see that the gospels themselves are not as useable as historical information as we might have hoped. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Professor Allen D. Callahan told PBS: “Well, there are what we might identify as contradictions in the account. Some of this has to do with our methodology. If we want to read the gospels as eye witness accounts, historical records and so on, then not only are we in for some tough going, I think there's evidence within the material itself that it's not intended to be read that way. I mean that there are certain concerns that are being addressed in this literature. And we become theologically and even historically tone deaf to those concerns, if we don't give them due consideration. It's now consensus in the New Testament scholarship to some extent [that]... in the gospels we're dealing with theologians, people who are reflecting theologically on Jesus already. And there's all indication that what we now refer to as theological reflection was there at the very beginning of things.... [Source: Allen D. Callahan, Associate Professor of New Testament, Harvard Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“They don't claim to be eye witness accounts of his life. I don't think that the people who are responsible for those documents were staying up at night worried about those kinds of things. They're making certain arguments and they have concerns..., and they are articulating those arguments and they're forwarding those concerns based on what they know and what other people know about what Jesus said and did.”

Gospels: Biographies, “"Religious Advertisements?”

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: “The gospels are not biographies in the modern sense of the word. Rather, they are stories told in such a way as to evoke a certain image of Jesus for a particular audience. They're trying to convey a message about Jesus, about his significance to the audience and thus we we have to think of them as a kind of preaching, as well as story telling. That's what the gospel, The Good News, is really all about. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Another view

“The four gospels that we find in the New Testament, are of course, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The first three of these are usually referred to as the "synoptic gospels," because they look at things in a similar way, or they are similar in the way that they tell the story. Of these then, Mark is the earliest, probably written between 70 and 75. Matthew is next - written somewhere between 75 and about 85, maybe even a little later than that. Luke is a little later still, being written between 80 and maybe 90 or 95. And, John's gospel is the latest, usually dated around 95, although it may have been completed slightly later than that, as well.

Professor Paula Fredriksen told PBS: “The gospels are very peculiar types of literature. They're not biographies. I mean, there are all sorts of details about Jesus that they're simply not interested in giving us. They are a kind of religious advertisement. What they do is proclaim their individual author's interpretation of the Christian message through the device of using Jesus of Nazareth as a spokesperson for the evangelist's position. The evangelist is not an author of fiction. The evangelist has traditions that go back through the Greek to the spoken language of Jesus, which was probably Aramaic. In other words, I think there's some kind of continuity between what Jesus would have been saying to other Jews in 27 to 30 and what the Evangelists in Greek are saying to their own communities, that Jesus said. But, as historians, we have to sift, and go through and try to figure out what corresponds mostly to the period of the composition in Greek and what corresponds to the lifetime of the historical Jesus. [Source: Paula Fredriksen, William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of the Appreciation of Scripture, Boston University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Images of Jesus and Symbols in the Gospels

Professor Paula Fredriksen told PBS: “The gospel tradition divides into two streams. There's Mark and there's John. Mark is the earliest gospel written, probably, shortly after the war that destroyed the Temple, the war between Rome and Judea. And Mark presents one type of Jesus with a particular narrative where Jesus begins in the Galilee and he ends his life in Jerusalem. John, a gospel that we can't date at all, has Jesus really with the Jerusalem ministry. He's scarcely in Galilee at all. And he's really talking and preaching and doing in Jerusalem. It's a quite different story and a quite different personality. Matthew and Luke depend on Mark. Which is why those three gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are called the synoptic gospels. Because they can be understood together. But in terms of literary dependency, Matthew and Luke construct their story around the plot provided by Mark. [Source: Paula Fredriksen, William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of the Appreciation of Scripture, Boston University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “Some of the symbols that Irenaeus uses of the gospels have come to be quite traditional and quite influential in the the symbolism associated with the gospels. So the ox, the lion, the winged man and the eagle that [are] used for the evangelists in many contexts, both artistic and literary, go back to Irenaeus. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Harmony of Synoptic Gospels page 1

“The eagle is the usual symbol for the Gospel of John, because his thought is so lofty and it flies so high. And the ox is the symbol of the third gospel, the gospel according to Luke, perhaps because of the way in which Jesus is presented as as someone born in a manger. It's unclear exactly why but that's certainly an element. The man with wings is associated with the Gospel of Matthew. And this may go back to traditions about Matthew having some sort of angelic assistance in the composition of his gospel.... Mark is symbolized by the lion, it's unclear why, but perhaps because the lion is a symbol of Jesus in the book of Revelation. And Mark does have connections with an apocalyptic view of Jesus.

Historical Constraints on Studying the Gospels

Professor Allen D. Callahan told PBS: “I think the historic story provides certain controls on our project of reconstruction. We just can't make Jesus anything that we want him to because we have certain historical constraints. Now, I also think that we're not the first people who have had these problems. I think these problems are very old. I think you start with the gospel writers, themselves.In other words, even though we're concerned about the gospel literature as being shot through with allkinds of tendencies and all kinds of biases and exaggerations and however we want to characterize these things, those guys who were responsible for that literature couldn't sit down and write anything that they wanted to about Jesus.... Among other things, they were writing for an audience, or audiences, who already knew something about Jesus; there was a market out there for their literature, and in order to engage that market, they really had to write about somebody that people knew about. They wanted to tell more about a figure about whom people already knew. And so they couldn't say any old thing. [Source: Allen D. Callahan, Associate Professor of New Testament, Harvard Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“And furthermore -- and other scholars wiser and smarter than I kind of smoked these places out -- [there are points in] the text that indicate that the gospel writers themselves were dealing with certain traditions about which they may be ambivalent, but nevertheless had to do something with them. [In] a classic example, Luke tells us about the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist. Now, if we read elsewhere in the Gospel of Luke [in]... the Acts of the Apostles, we see that Luke knows about the sect of John the Baptist. He knows that they preceded the Jesus movement and he also knows that there are some people in the Baptist Sect who insist on following the teachings of John the Baptist, even after Jesus has come on the scene, even after John is dead. And Luke doesn't like this....They were supposed to kind of get with the new franchise but they didn't.... He's concerned to show that even [though] John is a great guy, he's not greater than Jesus. But he knows that John baptized Jesus and that John was preaching of baptism of the repentance [of] sins. So, what does he do? ...In the third chapter of his gospel, he presents Jesus as coming to John the Baptist and then he says, "later John was put into prison." ... So, we get a notice that John was put in prison, and immediately following that notice, Jesus is baptized, it's in the passive, the verb's in the passive, with no mention of who baptized him. Now, we all know who baptized Jesus, and the smart money is that Luke knew who baptized Jesus but he didn't want to come right out and say, "John baptized him" because he doesn't like what that suggests, in the terms of the relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus....

Harmony of Synoptic Gospels page 1

Early Christians Interpreted Gospels Allegorically

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “At the time when the gospels were written, how did people read those documents? Did they read them the way we read a newspaper or a piece of history, at least with the hope, that is the factual rendition or are they reading it at a different level? [Source: Harold W. Attridge, Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Most of the people in the early Christian movement couldn't read so they wouldn't have been reading the gospels.... Probably the greatest contact they would have had is hearing these read or preached in connection with church services. Certainly what we think of today as literal interpretation of the scripture would not really have been available in quite the same way to people in the ancient world. I think it's important to understand that what contemporary Americans, for example, think of as a literal reading of scripture is really a product of the late 19th and early 20th century, as development or part of fundamentalism's reaction to Biblical scholarship and Biblical criticism as it had developed in the 19th century.

“Early Christians certainly read scripture allegorically, understanding it to refer to some kind of so-called higher realities that weren't really present in the text itself. They could interpret it morally, as giving advice for life. Very often in the 2nd and 3rd century, you find a kind of scriptural interpretation which we call "typological", and what that means is that events and details that are found in the Hebrew Bible are seen as types pointing ahead to the coming of Jesus. So that, for example, the scapegoat of the Book of Leviticus who bears off the sins of the Israelites is a type pointing ahead to Jesus and his bearing the sins of the world, according to Christian teaching....

“Since the Christians wanted to retain the Hebrew Bible as their scripture... it was necessary for them to make certain interpretive gestures to try to rein in the meaning of the Hebrew Bible text. Since clearly most early Christians, at least by the 2nd century, were not keeping details of the Jewish law they had a lot of correction to do, you might say, in terms of trying to say why this scripture was theirs and [why] they had the right to interpret it, but, on the other hand, why they weren't following the Jewish law, in the way that the Hebrew Bible detailed. That was quite an interpretive problem for the early Christians....

Gospels Parallels

“Most of the early Christians certainly would think that the gospel stories happened. They did have problems because there are so many discrepancies among and between the gospel stories which they themselves could notice, but they had a hard time perhaps putting them all together in what we would consider a literal kind of way. Basically, early Christians wanted to use these stories for moral edification. For a general message about salvation. Jesus lived. He died. He saved us from our sins. There's going to be an end to the world on judgment. A few basic phrases like that...

Evolution of the Four Gospels

Professor John Dominic Crossan told PBS: “Oral tradition is something that we have rather abused, I think, in scholarship. If you take, for example, the common material behind the Q gospel and the Gospel of Thomas, there's 37 sayings without any order so this is not a document of any type. Who is preserving it? The people who are living like Jesus, the itinerants who are trying to follow the life of Jesus. They are interested in these stories, not just because of oral tradition, but because it justifies their lifestyle. So whenever somebody says oral tradition, I want to say, "Could you show it to me? I know you can't show me oral tradition, but can you show it to me some way in the text, or at least, in the lifestyle of somebody who would have cared about it?" Otherwise we have a free-floating oral tradition that is becoming kind of meaningless. [Source: John Dominic Crossan, Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies DePaul University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“I think the Jesus traditions were preserved by those who were trying to live them. Whence, for example, those who preserved, "Blessed are the destitute." They preserved it because they were destitute and they thought they were blessed. They had a vested interest in remembering that saying because it described them.

“The first gospel, Mark, is around the year 70. So within 70 and, say, 95, we have the four gospels. 25 years. But that leaves 70 to 30. 40 years before that. If you watch the creativity within that 25 year span, from Mark being copied into Matthew and Luke, possibly also by John, then you have to face the creativity of that 40 years, even when you don't have written gospels. And that may be equally intense.

Gospels Parallels

“The gospels are, first of all, extremely reliable historical documents for their own time and place. Mark tells us very much about, say, a community writing in the 70's. John, a community writing in the mid-90's. But, since we have four of them, we get four vectors, then, on the basic tradition that they're working with. What is common, we might be able to then work, by going back very carefully through those deliberate... what scholars call "redactional" elements in there. If Mark just made it up any old way, and Matthew did the same, we could not do anything historically with them.

Differences among the Gospels

Professor John Dominic Crossan told PBS: “What the gospels do share, of course, is Jesus. But that is almost trivial to say that. Because they are interested in not simply repeating Jesus. They are interested in interpreting Jesus. Matthew, even when he has Mark in front of him, will change what Jesus says. And that's what's most important for me, to understand the mind of an evangelist. It is that Matthew is saying, "I will change Mark so that Mark's Jesus speaks to my people." Now, there's a logic to his change. He's not just changing it to be difficult. He will change Mark, but what Jesus says in Mark does not make sense to Matthew's people.... What is consistent about the gospels is that they change consistent with their own theology, with their own communities' needs. They do not change at random. If you begin to understand how Matthew changes Mark, you see it worked again and again and again. You don't have to make up a different reason for every change. Once you understand Matthew's theology, you can almost predict how he will change. [Source: John Dominic Crossan, Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies DePaul University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“For somebody who thinks the four gospels are like four witnesses in a court trying to tell exactly how the accident happened, as it were, this is extremely troubling. It is not at all troubling to me because they told me, quite honestly, that they were gospels. And a gospel is good news ... "good" and "news" ... updated interpretation. So when I went into Matthew, I did not expect journalism. I expected gospel. That's what I found. I have no problem with that. We have the problem, not Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. They do a superb job, or Christianity would not be still around, of doing what they had to do. We want them to be journalists and we're very unhappy with them.”

What's the significant difference between Matthew and Luke and Mark? What kind of differences do they bring in? “If you look at Luke 4, for example, the opening, almost paradigmatic, scene in Luke. Jesus goes into the synagogue. He takes the scroll of Isaiah. He is literate of course, he can read. And he's a scholar. He can find his way around an unpointed Hebrew scroll and find exactly the place he wants and reads it and comments on it. Jesus is a scholar. Jesus is rather like Luke, actually....Luke gives us his big scene up front. Matthew does the same with the Sermon on the Mount. It's on a mountain, where else? Moses is on a mountain ... Sinai. Jesus is on a mountain saying, "You've heard what was said to them of old, what I say to you." I couldn't imagine Matthew starting off with something else. Jesus is a new Moses. All of that is coherent within the theology of each evangelist....There is no Sermon on the Mount and there is no mountain to have a sermon on in Mark, and there is no scene in the synagogue at Nazareth where Jesus reads Isaiah and is almost killed. None of that is in Mark. One is in Matthew. The other is in Luke.”

Synoptic word for word

Comparing Mark with John

Professor John Dominic Crossan told PBS: “Let me compare Mark with John to explain how two gospels do it differently in an episode we call "the agony in the garden". Now, there is no agony in John and there is no garden in Mark, but we call it the agony in the garden because we put them together. Mark tells the story in which Jesus, the night before he dies, is prostrate on the ground, begging God, "If this all could pass, but I will do what you want." And the disciples all flee. Now that's an awful picture. That makes sense to me because Mark is writing to a persecuted community who know what it's like to die. That's how you die, feeling abandoned by God. [Source: John Dominic Crossan, Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies DePaul University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Over to John. Jesus is not on the ground in John. The whole cohort of the Jerusalem forces come out - 600 troops come out to capture Jesus, and they end up with their faces on the ground in John. And Jesus says, "Of course I will do what the Father wants." And Jesus tells them to "Let my disciples go." He's in command of the whole operation. You have a Jesus out of control almost in Mark, a Jesus totally in control in John. Both gospel. Neither of them are historical. I don't think either of them know exactly what happened. Mark is writing to a persecuted church, "Here is how to die ... like Jesus." John is writing, I think, to a community that's hanging on by its fingernails. It's getting more and more marginalized. Its Jesus is getting more and more in control, in control of the passion, in control of Pilate. The more John's community is out of control, the more Jesus is in control. Both of that makes absolute sense to me. But both are gospel.

“As I read John, I come to two conclusions. One is that this is a Jewish group. If you want to call them Christians, they're Jewish Christians. They're one group within Judaism. The second conclusion is that they are being more and more marginalized. That is, their appeal to lead all of Judaism is becoming less and less likely. They're becoming smaller and smaller and smaller. And they can refer to their fellow Jews as "the Jews". They are feeling profoundly alienated from their own Judaism. In plain language, they're losing. And that means the language of invective gets nastier and nastier. It's the loser in political campaigns that calls names. So, Matthew is losing when he calls the Pharisees hypocrites and says "war to them." That warns me that he is losing out to the Pharisees as he sees it. John, he talks about "the Jews did this" or that awful statement about the Jews are born of the Devil. That tells me that this community is desperate. It's hanging on by its fingernails.

Tension Between Christians and Jews in the Gospels

One theory of how the Synoptic Gospels originated

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “In all of the gospels there are statements that reflect the growing polemical situation or situation of controversy between the Christian movement toward the end of the first century and Jewish communities of that time. In Matthew for instance, there are the "Woes on the Pharisees," whereas at the same time we have statements about Jesus coming to fulfill the law. So there seems to be a debate between Matthew and some observant Jews or Jewish Christians about the law. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“In Luke and in John, that kind of polemic is intensified in various ways. Particularly in John, we have statements about the Jews put on the lips of Jesus which distinguish them as a group alien to Jesus and his followers, which is the farthest thing possible from the historical reality, and demonize [them]. So, for instance, in John 8, we have the statement that the Jews are children of Satan, and Satan is the murderer from all time. Those kinds of statements indicated there was an intense polemical relationship between Jews and Christians at that point. The basis for that relationship seems to have been a separation between the Johannite community and the group of Jews from which they came.”

Is this also the roots of Christian anti-Semitism? “The kind of polemic and the sorts of things that were said by Christians about Jews in the gospels certainly... played a role in Christian anti-Semitism, and it's certainly something that the Christian churches need to grapple with as they appropriate the gospel tradition.

Role of Jews in the Gospels' Accounts of Jesus' Death

Koester theory on how the Gospels originated

Professor John Dominic Crossan told PBS: “In terms of the execution of Jesus, we know from the Roman historian Tacitus, and the Jewish historian Josephus, that there was a movement, that the founder was executed, and that the movement continued ... three very important things. So, the brute facts, as it were, are as certain as historical things can be. When you turn, however, to the details, to the blow by blow, moment by moment, word by word accounts that you find in Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John, that's a very different thing because what's interesting there is that it looks like it's a single stream of tradition, not four independent witnesses. Mark is copied into Matthew and Luke and may well be copied into John, so it's only a single source for all of this. What you find throughout that source, is that as this group ... the Christian Jews, we're talking about ... a group of Jews similar to the Essene Jews or the Pharisaic Jews or the Sadducean Jews, or the Zealot Jews ... as the Christian Jews become more and more marginalized and alienated from the majority ... of their own people, the enemies of Jesus in this story similarly get increased. So Mark talks about the crowd being against Jesus, but by Matthew, 15 years later, say in the year 85, it's all the people. And by the time you get to John in the 90's, it is the Jews who are against Jesus in the passion. [Source: John Dominic Crossan, Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies DePaul University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“The difficulty for us is to take the term "gospel" seriously. It means "good news." "Good" is from somebody's point of view, not the Roman point of view, for example. "News" means "updated" so the story had to be updated. Any gospel writer, when they're writing the passion of Jesus, asks themselves, as it were, "Who are my enemies here, today, now? They are the enemies of Jesus way back in the 20's." That becomes terribly dangerous as you watch the Christian gospels..., even John talking about the Jews, means all those other Jews, except us "good" Jews. And he's admitting, sort of, that the majority is going steadily against him. When that is read in the fourth century by pagans with the Roman Empire behind them, that becomes the lethal seedbed out of which, eventually, genocide and anti-Semitism, in our own days, would eventually come. Because after all, we're now reading that the Jews did this. And that means that those people over there who are not us.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024