Home | Category: Jewish People in 19th and 20th Century

ZIONISM

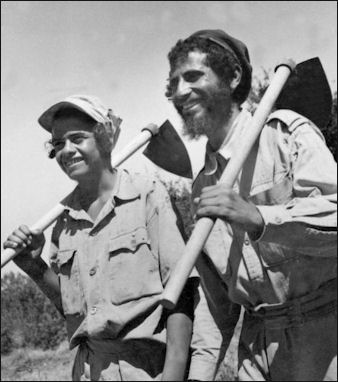

New immigrants to Israel Zionism is an international political movement that supports a homeland for the Jewish People in the Land of Israel. Beginning in about the mid-nineteenth century many Jews began to dream of a safe, permanent homeland in Palestine, the land where Judaism historically originated. This became a movement called Zionism. The dream is said that have its origins in A.D. 70 when Roman troops sacked Jerusalem, massacred the Jews, and destroyed the Temple, and in A.D. 132 ce when hundreds of thousands of Jews were massacred or enslaved, and their survivors were banished from what is now Israel.

Zionism calls for the creation of a Jewish homeland state in Biblical Israel. It is based on the practical idea of establishing a nation for Jews and rooted in the spiritual idea of returning to Zion (the promised land or Jerusalem), referred to as the Land of Israel (Eretz Israel ). "Zion" being is one the biblical names for Jerusalem. Mount Zion is a place in the in the Old City of Jerusalem, where it is said David was buried (and Christ had his Last Supper).

It has been said that the history of modern Israel began with the articulation of Zionism as a blueprint for Jewish nation and cultural revival. According to the Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Zionism was a reaction to virulent and increasingly violent European anti-Semitism (which culminated in the terrible Holocaust of 1933-1945), but it was also a response to the nationalist movements of other, especially eastern and southern, European peoples throughout the nineteenth century. Zionism stressed the physical relocation of Jews to Palestine (in Hebrew, Aliya), and in 1882 the first wave of these "modern" immigrants — politically and ideologically, rather than religiously, motivated — arrived. This first wave effectively doubled the Jewish population of Palestine (from about 24,000 in 1881).

Zionism was also based on the idea of uniting Jews scattered all over the world in a single homeland. Theodore Herzl, the regarded as the father of Zionism, said in 1897, “Zionism has already brought about something remarkable, heretofore regarded as impossible: a close union between the ultramodern and the ultraconservative elements of Jewry.” Although the name Zionism conjures up images of religious extremists, its 19th century founders Zionism were antireligious European intellectuals inspired not by religion but by socialist and nationalist sentiments prevalent in Europe at that time. The Zionist Congress of 1897 was fundamentally a nationalist movement. It stated in its final resolution that “the goal of Zionism is the establishment for the Jewish people of a home in Palestine guaranteed by public law.”

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Herzl’s Vision: Theodor Herzl and the Foundation of the Jewish State” By Shlomo Avineri (BlueBridge, 2015) Amazon.com ;

“From Herzl to Rabin: The Changing Image of Zionism” by Amnon Rubenstein (Holmes & Meier Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews Volume Two: Belonging: 1492-1900 by Simon Schama Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com ;

“The Lost World of Russia's Jews: Ethnography and Folklore in the Pale of Settlement” by Abraham Rechtman, Nathaniel Deutsch , et al. Amazon.com ;

“Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History” by Steven J. Zipperstein Amazon.com ;

“Pogroms: A Documentary History” by Eugene M. Avrutin and Elissa Bemporad Amazon.com ;

Jewish Homeland

The Zionist movement was rooted in centuries of Jewish prayer and yearning to return to the land of Israel. The Old Testaments describes the Jews as God’s Chosen People and describes three different sets of boundaries for Israel; the book of Prophets, three more; and the Rabbinic authorities, a seventh. According to Joshua 15:1-12, God gave Judah, the forth son of the Patriarch Jacob, the relatively modest chunk of land between the Dead Sea and the Mediterranean.

Children of Zionism The Jewish kingdom reached its greatest extent under David around 1000 B.C. when it stretched from the Sinai to the Euphrates River and included large chunks of present-day Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt. David’s kingdom lasted less than a century but it fulfilled a promise made by God to Abraham (Genesis 15:18): “To your offspring assign this land, from the river of Egypt [in the Sinai] to the great river, the river Euphrates.” Centuries after David’s kingdom was lost, the Prophet Ezekial dreamed (47:13-20) of Israel’s exiles returning to a land restored to borders of David’s kingdom.

In Deuteronomy 11:24-25 God promised Moses: “Every spot on which your foot treads shall be yours; your territory shall extend from wilderness to the Lebanon and from the River — the River Euphrates — to the Western Sea [the Mediterranean]. No man shall stand up to you; the Lord Your God will put the dread and fear of you over the whole land in which you set foot, as he promised you.”

Zionist dream is regarded as unfilled in part because most of the world’s Jews chose not move to Israel and Jewish suffering outside of Israel has not occurred. Of the world’s 16 or so million Jews only 9.4 million live in Israel. Until fairly recently more Jews lived in the United States than in Israel.

Vladimir Jabotinsky was a rightist Zionist visionary who called for the creation of a Israel that covered the territory described in the Bible. Conversely, the founders of Zionism did not seek another sacred, anointed state defined by the Old Testament. Rather they wanted to establish a secular democracy with full equality for Arab citizens.

Zionism Timeline

1210 — Group of 300 French and English rabbis make aliyah — the immigration of Jews from the diaspora to Israel- Palestine region — and settle in Israel.

1163 — Benjamin of Toledo writes of 40,000 Jews living in Baghdad, complete with 28 synagogues and 10 Torah academies.

1211 — A group of 300 rabbis from France and England settle in Palestine (Eretz Yisrael), beginning what might be interpreted as Zionist aliyah.

1785-1851 — Zionist author, journalist and and diplomat, Mordechai Manuel Noah.

1812-1875 — Moses Hess, author, socialist and Zionist.

1821-1891 — Well-known physician and early Zionist, Leon Pinsker.

1861-1936 — Essayist and publicist who headed the Jewish and Zionist Organization during the 1930s, was editor of He-Tsefriah and published a history of Zionism, Nahum Sokolow.

1864 — Leon Pinsker writes Autoemancipation and argues for creation of a Jewish state.

1866 — Jews become a majority in Jerusalem.

1845-1934 — Zionist leader Baron Edmond James de Rothschild.

1860-1904 — Father of Zionism, Theodore Herzl.

1873-1934 — Poet laureate of the Jewish national movement, authored "In City of Slaughter," "El Ha Tsippor-To the Bird" and "Metai Midbar-Dead of the Desert, Hayim Nahman Bialik.

1880-1920 — Zionist leader Joseph Trumpeldor.

1880-1939 — Zionist leader, founder of the New Zionist Organization, Haganah, Jewish Legion, Irgun, Betar, Revisionist Party, Vladimir Jabotinsky.

1882 — Hibbat Tzion societies founded.

1884 — First Conference of Hovevei Zion Movement.

1891 — Christian Zionist William E. Blackstone and 413 prominent Americans petition President Benjamin Harrison to support resettlement of Russian Jews in Palestine.

1896 — Theodor Herzl publishes Der Judenstaat, The Jewish State (Zionism): .

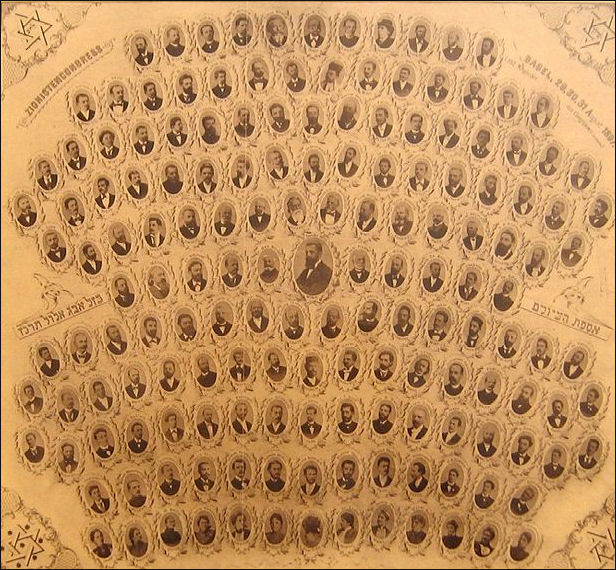

August 29, 1897 — First Jewish Zionist congress convened by Theodor Herzl in Basle, Switzerland, Zionist Organization Founded.

1899 — Theodor Herzl establishes the Jewish Colonial Trust, the financial arm of the Zionist movement.

Illegal Immigrants to Israel

1901 — The Fifth Zionist Congress decides to establish Keren Kayemet LeIsrael (KKL) — The Jewish National Fund.

1902 — Theodor Herzl publishes a romantic utopian novel, Altneuland, Old-New Land, a vision of the Jewish State.

1903 — British Government proposes "Uganda Scheme," rejected by the Sixth Zionist Congress.

August 26, 1903 — Herzl proposes Kenya as a safe haven for Jews.

1905 — Zionist Labor Party (Poale Zion) formed in Minsk in an effort to combine Zionism and Socialism.

1911 — Palestinan journalist Najib Nasser publishes first book in Arabic on Zionism entitled, "Zionism: Its History, Objectives and Importance." Palestinian newspaper Filastin begins addressing its readers as "Palestinians" and warns them about Zionism.

1912 — Henrietta Szold founds Hadassah, the Women's Zionist Organization.

1912 — Agudah (Agudat Israel) formed as the World Organization of Orthodox Jewry at Katowitz.

1913 — First Arab Nationalist Congress meets in Paris.

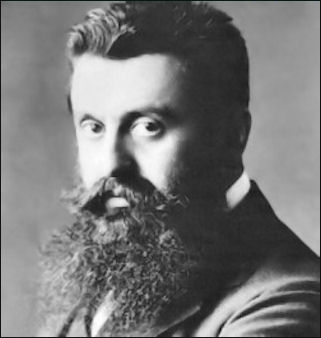

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (1860-1904), the father of modern Zionism, was an assimilated Budapest Jew who worked as a journalist in Vienna. At first he advocated assimilation of Jews into Gentile society as a solution to the Jew’s problems. He took up the cause of establishing a Jewish homeland in Israel (Zionism) when he came to the conclusion that anti-Semitism was ingrained in Europe after covering the Dreyfus Trial in Paris (in which a French Jewish officer was imprisoned on trumped up charges).

Herzl wasn’t the first person to propose the idea of a Jewish state but he was the first to offer a plan of how such a state could be realized in the modern world. Herzl said, "Dream is not so different from deed as long as many believe...The Jews who wish it will have their state and they will earn it."

Herzl took up the Zionist cause when he was in his mid-30s and devoted the rest of his life to it. He described his dream in a series of books. In his 1886 book “Der Judenstaat” (“The Jewish State”) he argued that Jews would never fit into Europe and that establishing a Jewish homeland was the only way they ever be secure and at peace. In his 1902 utopian “Altneukabd” (“Old-New Land”) he described a world in which Jewish Palestine was the center of commerce.

Herzl wrote letters to influential men throughout Europe on the importance of creating a Jewish homeland organized the first International Zionist Congress in 1897 in Basel, Switzerland and helped set up Zionist organizations in all countries where there were a large Jewish populations

In a review of the book “Herzl’s Vision”by Shlomo Avineri, Jonathan Kirsch of Washington Post writes: Flesh-and-blood Herzl has almost disappeared under the weight of his place in history.” Herzl “was a highly assimilated Viennese Jew, a disappointed playwright and a rather more successful journalist when he was drawn to the notion of solving the so-called Jewish Problem by creating a Jewish homeland somewhere in the world. He did not speak Hebrew: “Who amongst us,” he mused, “has a sufficient acquaintance with Hebrew to ask for a railway-ticket in that language?” With the publication of “The Jewish State” in 1896, however, Herzl rose to the international leadership of political Zionism, thereby transforming the movement “from an esoteric, if not cranky, idea into a player on the international scene.” [Source:Jonathan Kirsch, Washington Post, January 2, 2015]

Herzl “Unlike other founding fathers and mothers of Zionism, Herzl was not one of the chalutzim, the pioneers who, starting in the late 19th century, traveled to Palestine to turn the soil of the Promised Land with their own hands. Rather, his approach to Zionism was typical of the traditional survival strategies of the Diaspora — that is, he sought out the rich, powerful and wealthy in the hope of enlisting their support for the Zionist project.” This is best illustrated by his “momentous tour of the Middle East during which Herzl won an audience with the kaiser of imperial Germany in 1898. Even Herzl’s idea was dismissed, Avineri points out, “it was the first time the world’s major movers and shakers had considered it and taken a stand about it — even if to negate it..“The Zionist idea was on the world’s map and would from this point onward be a factor in international relations.” The Balfour Declaration in 1917 was essentially the same package wrapped in the colors of the British Empire. Avineri credits Herzl with the “phenomenal achievement” of transforming the idea of a Jewish state “from one bandied about by a small coterie of educated but marginal Jews to an item on the international political agenda, a position which it keeps to this day.”

“Avineri sees the profound irony in Herzl’s vision. He lived in an era that Avineri characterizes as “one of the best times ever for European Jews,” a time and place that afforded remarkable new opportunities to Jewish communities that had long been confined to the ghettos and burdened with legal disabilities. Although the point is moot nowadays, Herzl was willing to entertain the idea that a Jewish homeland did not necessarily require a foothold in Palestine: “Argentina or Palestine” was one of the questions he pondered in “The Jewish State,” and he was open to talking about Uganda, too, if only as a place of refuge in the wake of a wave of pogroms in Russia. Yet he was astute enough to realize that only Palestine resonated in the hearts of his readers: “Palestine is our never-to-be-forgotten homeland.”

Although Herzl is one of the foundational figures in Zionism and the state of Israel he insisted that the Arabs in Palestine be given equal rights and play a political role in a Jewish state. He recognized that a Jewish homeland in Palestine should not be exclusively Jewish. “And if it should occur that men of other creeds and nationalities come to live among us, we should accord them honorable protection and equality before the law,” Herzl wrote. “We learned toleration in Europe. This is not said sarcastically.”

Zionism to Secular and Religious Jews

After its articulation Zionism became different things to different people. To religious Jews, Zionism was the idea of returning to Jerusalem as the religious homeland of the Jews: a metaphysical place deep-seated in the Jewish consciousness, an answer to 2,000 years of prayers. It was a “divinely ordained” and “intrinsically holy” idea expressed throughout the centuries by the expression of hope and promise, “Next year in Jerusalem.”

To secular Jews, Zionism expressed the dream of creating modern Jews that ascribed to the same principalis as altruist, socialist gentiles. Dr. Chaoim Weizmann, a leading spokesman and negotiator for the Zionist cause, said: “There should be one place in the world, in God’s wide world, where we could live and express ourselves in accordance with our character and make our contribution.” The Zionist curriculum in schools has traditionally attempted to downplay the experience of the Jewish people and their connection to the land while promoting universal values and history. For others Zionism was justice for 2,000 of years of exile, discrimination and murder directed at the Jews and a guarantee that such things would not happen again. These people argue that if Israel been created a decade earlier the Holocaust would never happened.

Professor Joshua Shanes wrote: The first Zionists were mostly secular Jews from Eastern Europe. Inspired by nationalist movements around them, they claimed that Jews constituted a modern nation, rather than just a religion. Traditions and prayers connected to the land — often reinterpreted through a secular, nationalist lens — became all-important for Zionists, while many other rituals and traditions were abandoned.[Source: Joshua Shanes, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies, College of Charleston, The Conversation, June 15, 2023]

Most Jews opposed Zionism for decades. Reform Jews and even some early Orthodox Jews worried that defining Jews as a “nation” would undermine their claim to equal citizenship in other countries. Orthodox Jews, meanwhile, opposed Zionists’ staunch secularism and emphasized that Jews must wait for the Messiah to lead them back to the land of Israel. Within a decade or two of Israel’s establishment as a modern state, however, most Jewish denominations integrated Zionism into their worldview. Still, most ultra-Orthodox Jews today continue to oppose Zionist ideology, even as they hold right-wing political views on Israel. Young liberal Jews, too, are increasingly emphasizing the distinction between Zionism and their own Jewish identity.

Jews, Israel, Zionism and Religion

In the 17th century a charismatic rabbi by the name of Shabbetal Tzezi urged his followers to re-establish Israel in the Ottoman Empire. The Turkish sultan ultimately caught up with him and gave him a choice: convert to Islam or be put to death, he chose the former and to this day some descendants of his disciples practice a Jewish-flavored Islam.

Many Orthodox Jews believe the Torah states that Israel can not be created until the Messiah comes, thus posing them with a dilemma when Israel was founded in 1948. Some decided to reconcile their beliefs with “the facts on the ground” as Ariel Sharon later put it. Some refused, including the Satmar Hasidim, a large group of ultra-Orthodox Jews. To this day two Orthodox prayer books are printed, with one leaving out the “Prayer for the State of Israel.”

Zionism has few links with religion and is viewed by ultra-Orthodox Judaism as backward. The founding Zionist fathers would be appalled by the power and influence of ultra-Orthodox in Israel today. Hannah Arendt, the author “Eichmann in Jerusalem” and the source of term “Banality of Evil,” was against Zionism. She said that Jews no longer believed in God; they only believed in themselves. “In this sense,” she said “I don’t like the Jews.”

According to an advertisements run by the True Torah Jews in the Washington Post and New York Times and other newspapers: “Zionism is not Judaism. The Zionist ideology is fundamentally anti-Torah. Zionism has not only denied the fundamental Jewish belief in Heavenly Redemption it has created a pseudo-Judaism which replaces the Torah with nationalism...Thus, the State of Israel cannot — and should not — claim to represent worldwide Jewry....True Torah Jews are outraged by this ongoing ploy, in which the Zionists attempt to create the impression that the holy Torah is behind their hard-line , nationalistic goals. It is not!”

Zionism and Modern Jewry

Torah Book in Porat A movement to create a Jewish homeland began in the mid 19th century when Jewish populations were exploding, poverty was rampant, waves of pogroms were being leveled against the Jews and large numbers of Jews were migrating to the United States and western Europe, where they were assimilating into dominate cultures, making contributions to these cultures and being influenced by ideas of socialism and nationalism.

Judaism and the Jewish people have been affected and shaped very much by two 20th century events: the Holocaust and the creation of Israel. Although these events were historical in nature had religious overtones in their interpretation as the destiny of a people chosen by God to suffer and fulfill a special destiny.

Secularism was embraced by many Jews. In the United States there were only five Jewish day schools in the whole country in the early 20th century. By 1930, only a third of Jews belonged to a synagogue, and only a quarter of Jewish children were receiving any kind of religious instruction. Hebrew all but died out and Jewish scholars lamented about “institutional decay” of American Judaism. Jewish identity was still strong but it was based on Jewish culture, Zionism and campaigns against anti-Semitism rather than on religion.

Judaism and the Jewish people have also been shaped by the existence of America, with America representing the Jewish Diaspora and its reformed ideas about both religion and politics and Israel representing the Jewish nation with its view about religion and politics.

Many modern Israelis believe that Zionism has been a success. One Israeli Zionist told the Los Angeles Times, “We came to Israel to build a state so that the word ‘victim’ wouldn’t be part of our vocabulary. It strikes at a very deep chord.” Many Jews feel they were too passive during the Holocaust when they were led to the Nazi gas chambers “like sheep to the slaughter.”

Jews who criticise Israel are sometimes condemned as 'self-loathing' by members of their own community. Devout Jews pray daily for Israel — or Zion as it's known in the ancient texts. Israel and Zionism are sensitive subjects, regarded as going to the heart of what it means to be Jewish. [Source: Jonathan Freedland, BBC, July 7, 2009 |::|]

Judaism, Nationalism and Zionism

Louis Jacobs wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The Zionist movement posed an acute form a problem which had agitated Jewish minds for some time — the role of nationalism in Judaism. Were the Jews merely adherents of a common religion — as it was put, Germans, Frenchmen, Englishmen of the Mosaic persuasion — or were they a nation? Was Judaism dependent for its fullest realization on residence in the Holy Land, or was it desirable that Jews be dispersed in many lands to further there the "mission of Israel" in bringing God to mankind in the purest form of teaching? These questions were being asked, and the replies varied considerably. [Source: Louis Jacobs, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1990s, Encyclopedia.com]

The early Reformers deleted from the prayer book all references to national restoration. Exile was not seen as an evil to be redressed but as an essential step in the fulfillment of the divine purpose. The Reformers were not alone in their opposition to a nationalistic interpretation of Judaism. When political Zionism became a practical policy for Jews, many of the Orthodox opposed it as a denial of Jewish messianism according to which, it was believed, the redemption would come through direct divine intervention, not at the hands of men. There were not lacking, however, religious leaders who advocated a form of religious Zionism, claiming that, as in other spheres, the divine blessing follows on prior human effort.

With the actual establishment of the State of Israel the older attitudes became academic. With the exception of the fringe groups of the Neturei Karta (Orthodox) and the American Council for Judaism (Reform), the majority of Jews now accept the special role the new state has to play as a spiritual center (over and above the haven of refuge it provides), while generally acknowledging that to uncover the full implications of this concept requires a good deal of fresh thinking. Some Orthodox thinkers have taken refuge in the notion of the establishment of the State of Israel as at alta di-ge'ullah ("the beginning of the redemption"), i.e., that while complete redemption is at the hands of God through the Messiah, the present life of the State still has messianic overtones and belongs in a realm far removed from the secular. Some see this as an unsuccessful attempt literally to have the best of both worlds.

Zionism and the Creation of Israel

Israel was set up with the purpose of providing a home and shelter for Jews. This concept is tied up with the idea of Zionism as a secular movement based on the idea that Israel was a nation like any another except that it lacked a homeland and the goal was to create a secular homeland for them. Religious Zionists embraced the movement as fulfillment of Judaic doctrines, Biblical prophecies and destinies of the Jewish people as dictated by God.

Political Zionism began in the mid-19th Century and towards the end of the century it gained strength as many Jews began to feel that the only way they could live in safety would be to have a country of their own. Some have argued that Zionism developed as a response to the inability of the Jews to emancipate themselves socially from the world they lived in and felt they had no other choice but to create their own homeland.

In the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the British Government agreed that a national home for Jewish people should be established in Palestine. Following the First World War, the British governed the region in preparation for a permanent political arrangement. Over the next few years Jewish immigration increased and important institutions were founded such as the Israeli Chief Rabbinate, and the Hebrew University.

Chaim Wiezmann (1874–1952) was instrumental in the planning for a Jewish state in Israel. A native of Russia, he studied biochemistry and worked with the Allies during World War I. Weizmann made many connections with British leaders through his work and was influential in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which Britain announced its support for a Jewish state in Palestine. Additionally, the British appointed him to advise on the formation of such a state. During World War II, when Jews were being targeted for extermination by Nazi Germany, Weizmann tried to prevent the restriction of Jewish immigration into Palestine, though he was unsuccessful. After the war he was involved with partition plan presented before the United Nations, which established boundaries for the proposed Jewish state in Palestine. The state of Israel was declared in 1947, and Weizmann served as its first president, a position he held until his death.

First World Zionist Congress delegates

Zionism, Anti-Zionism and Anti-Semitism

Jonathan Weisman wrote in The New York Times: Zionism as a concept was once clearly understood: the belief that Jews, who have endured persecution for millenniums, needed refuge and self-determination in the land of their ancestors. The word still evokes joyful pride among many Jews in the state of Israel, which was established 75 years ago and repeatedly defended itself against attacks from Arab neighbors that aimed to annihilate it.[Source: Jonathan Weisman, The New York Times, December 11, 2023]

If anti-Zionism a century ago meant opposing the international effort to set up a Jewish state in what was then a British-controlled territory called Palestine, it now suggests the elimination of Israel as the sovereign homeland of the Jews. That, many Jews in Israel and the diaspora say, is indistinguishable from hatred of Jews generally, or antisemitism.

Yet some critics of Israel say they equate Zionism with a continuing project of expanding the Jewish state. That effort animates an Israeli government bent on settling ever more parts of the West Bank that some Israelis, as well as the United States and other Western powers, had proposed as a separate state for the Palestinian people. Expanding those settlements, to Israel’s critics, conjures images of “settler colonialists” and apartheid-style oppressors.

So for some Jews, the answer to the question is obvious. Of course anti-Zionism is antisemitism, they say: Around half the world’s Jews live in Israel, and destroying it, or ending its status as a refuge where they are assured of governing themselves, would imperil a people who have faced annihilation time and again. “There is no debate,” said Jonathan Greenblatt, the CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, which has been defining and monitoring antisemitism since 1913. “Anti-Zionism is predicated on one concept, the denial of rights to one people.”

Many Palestinians and their allies recoil just as fiercely: The equating of opposition to a Jewish state on once-Arab land — or opposition to its expansion — with bigotry is to silence their national aspirations, muffle political dissent and denigrate 75 years of their suffering. Laila el-Haddad, a Palestinian activist and author, called it “a chilling attempt to punish and silence voices critical of Israeli policies.”

But perhaps nowhere is the question more fraught than among Jews themselves. Younger, left-leaning Jews, steeped in the cause of anti-racism and terms such as “settler colonialism,” are increasingly searching for a Jewish identity centered more on religious values like the pursuit of justice and repairing the world than on collective nationalism tied to the land of Israel. Many older liberal Jews have also struggled with the Israeli government’s lurch to the far right, but they see Israel as the centerpiece and guarantor of continued Jewish existence in an ever more secular world. “We’re living in an increasingly post-religious age, and any Jewish community that walks away from the Jewish people, and its most articulate expression of our times — the Jewish state, the state of Israel — is walking away from their own future,” said Ammiel Hirsch, the senior rabbi of Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in New York City and the founder of Amplify Israel, which seeks to emphasize the Jewish state in Jewish worship.

Complicated Distinction Between Anti-Zionism and Anti-Semitism

The distinction between anti-Zionism and anti-semitism is complicated and even Jews and Israel’s most ardent defenders can disagree of their definitions. Jonathan Jacoby, the director of the Nexus Task Force, a group of academics and Jewish activists affiliated with the Bard Center for the Study of Hate, told the New York Times the group had wrestled with the issue for several years now, seeking a definition of antisemitism that captures when anti-Zionism crosses from political belief to bigotry. He warned that shouting down any political action directed against Israel as antisemitic made it harder for Jews to call out actual antisemitism, while stifling honest conversation about Israel’s government and U.S. policy toward it. [Source: Jonathan Weisman, The New York Times, December 11, 2023]

The definition of antisemitism as drafted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance and embraced by the Trump White House includes phrases that critics say squelch political — not hate — speech: 1) Denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, such as by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor. 2) Applying double standards by requiring of Israel behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation. 3) Comparing contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.

Wesiman wrote: The Nexus definition agrees that holding Jews around the world responsible for Israeli government actions, as pro-Palestinian protesters did last week outside an Israeli restaurant in Philadelphia, is Jew hatred. It also holds that it is antisemitic to reject the right of Jews alone to define themselves as a people and exercise self-determination, as some on the left do in arguing that Jews are a religion, not a nation. But Nexus pushes back sharply on some aspects of the IHRA definition, stating, “Paying disproportionate attention to Israel and treating Israel differently than other countries is not prima-facie proof of antisemitism” and “Opposition to Zionism and/or Israel does not necessarily reflect specific anti-Jewish animus.”

Yehuda Kurtzer, the president of the Shalom Hartman Institute, a Jewish research organization, said that Judaism had always contained elements of religion and nationhood, and that Jewish identity had toggled between the two over the millenniums. It is unsurprising that the two strains can seem baffling, he said.

Since the rise of violent white supremacy that accompanied the political movement of Trump, Jewish intellectuals have viewed right-wing antisemitism “as dangerous to Jewish bodies,” Kurtzer continued. The 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue massacre that took 11 Jewish lives was perpetrated by an adherent to the “great replacement” theory, a conspiratorial fiction designed to create race hatred by holding that Jews are importing Black and brown people to supplant white Americans.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024