Home | Category: Jewish People in 19th and 20th Century / Jewish Groups in Europe, Russia and America / Jewish Groups in the Former Soviet Union and Asia / Jewish Sects and Religious Groups

EARLY HISTORY OF JEWS IN RUSSIA

Mountain Jews in Russia Jewish settlers are believed to have arrived in the Crimea and the Black Sea area as early as the last centuries B.C.

In the 9th century the Khazars, a Turkic tribe in Russia, converted en masse to Judaism. The Khazar Khan Turk Bulan underwent a ritual circumcision. Some say the conversion was as much of political move by the Khazars — to distance themselves from the Christian Byzantines and Muslim Arabs — as a religious one. Some attribute the Khazar’s conversion to the influence of the people that became known as Mountain Jews of the Caucasus. There were many Jewish aristocrats, merchants and advisors from the Caucasus in the Khazar court before the Khazars converted.

Recent genetic studies indicate that Levites, an ancient caste of heredity Jewish priests, of Ashkenazi descent originated in Central Asia not the Middle East. Ashkenazim is one of the two main branches of Jews (the other is Sephardism). Most American Jews are of Ashkenazi descent. The genetic studies found that 52 percent of the Levites of Ashkenazi have a particular genetic marker that originated in Central Asia. Some scholars have theorized that the markers were introduced by the Khazars and the Jews that descended from the Khazars became integrated and influential in the worldwide Jewish community. This has great implication on the belief that Jewish priests are the descendants of the Chosen People tribes from Israel.

Between the 14th and 18th century a large number of Jews moved to the Crimean and the Black Sea region from the Spain and the Mediterranean countries, eastern Europe and to a lesser extent the Caucasus and Persia.

See Separate Articles: JEWS IN RUSSIA factsanddetails.com; HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN RUSSIA factsanddetails.com; JEWISH GROUPS IN RUSSIA AND THE FORMER SOVIET UNION factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Lost World of Russia's Jews: Ethnography and Folklore in the Pale of Settlement” by Abraham Rechtman, Nathaniel Deutsch , et al. Amazon.com ;

“Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History” by Steven J. Zipperstein Amazon.com ;

“Pogroms: A Documentary History” by Eugene M. Avrutin and Elissa Bemporad Amazon.com ;

“The Khazars: A Judeo-Turkish Empire on the Steppes, 7th–11th Centuries AD (Illustrated) by Mikhail Zhirohov Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews Volume Two: Belonging: 1492-1900 by Simon Schama Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com ;

“Herzl’s Vision: Theodor Herzl and the Foundation of the Jewish State” By Shlomo Avineri (BlueBridge, 2015) Amazon.com ;

“From Herzl to Rabin: The Changing Image of Zionism” by Amnon Rubenstein (Holmes & Meier Amazon.com

Jews in Eastern Europe

By the 16th century, most of the world’s Jews were concentrated in Poland, then the largest kingdom in Europe and one that included what is now Lithuania, Belarus and western Ukraine.

Jews first arrived in Poland in large numbers during the Crusades to escape persecution in Germany. They were welcomed in the 14th century by Poland's King Kazimierz III who hoped they would bring urban skills to his largely peasant kingdom. For two centuries the Jews were members of the privileged class and many Poles married off their daughter to Jewish merchants to move up in the world.

Prague was famous for its Jewish theologians, philosophers, mystics, sorcerers and alchemists. The "terrible" Rabbi Judah Lowe ben Bezalel was a 16th century astrologer who reputedly created a golem, a creature brought to life from clay with a magic inscription called a shem. A sort Jewish version of Aladdin’s genie, golem served anyone who awakened it and was supposed to come the rescue of the Jewish people in their hour of need.

This period of Jewish tolerance and enlightenment came to an end during the Counter-Reformation of the 16th century when Jews were so badly persecuted many of them converted to Catholicism.

Later History of Jews in Russia

1917.jpg)

Jews of Khorostkiv, Ukraine, 1917 When Poland was broken up and absorbed by its neighbors in the 18th century most Jews ended up in the Russian Empire. About a half million Jews arrived after the partition of Poland in 1772-95. Most were restricted and forced by law to live in the so called Pale of Settlement, or the Western Pale, on the western fringes of the Russian empire.

The Pale of Settlement was huge ghetto that occupied former Polish territories in in present-day Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and eastern Poland. Jews were prohibited from living in cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg. The were required to pay a double tax. In the 19th century, many Jews adopted Russian-sounding names to avoid prejudice.

When Jews arrived in the Western Pale, Christian peasants still made of the bulk of the population there. They lived in agricultural villages as “serfs” (essentially slaves that could be bought and sold) until they were liberated in 1861. Jews made up only about 1 percent of the population of villages, where they made flour mills, ran taverns, and peddled merchandise and crafts. They prospered in towns and constituted the majority in hundreds of towns that spread and grew over a large territory. “Fiddler on the Roof” is set in this part of Russia at this time.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the Jewish population in the Pale grew rapidly: four or five fold. Jews constituted two-thirds of the population and made up a half to two thirds of the residents in the cities. From the cities Jews dominated much of the economy in western Russia. Even though they were denied basic rights such owning land and holding government jobs, Jews prospered by developing local light industries such as paper, wood and things like hog bristle brushes exported to England — artisan crafts, banking and trade. They had their own education systems, hospitals, charities and professional organizations, literature, publishers and newspapers. Intellectual life was divided between Talmudic scholarship and the Haskalah, influenced by secularism, liberalism and the enlightenment. A typical 19th century Jewish town was called a “shtetl”.

Beyond the Pale

Towards the end of the 1700s Jews began to suffer persecution in central Europe, and in Russia they began to be restricted to living in a particular area of the country, called The Pale. "The Pale " is a strip of land stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea, running chiefly through the Polish provinces. Save by special privilege, no Jew is allowed to make his home elsewhere than within this Pale.

The Jewish presence in Russia grew as a result of Russia, Prussia and Austria’s division of Poland at the end of the 1700s. Along with the Polish territory it gained, the Russian Empire inherited approximately 1 million Jews. Most of the Jewish population was densely concentrated in rural areas in the north and west of the Russian Empire. Later Tsarist decrees forbade Jews from settling outside of a prescribed area, known as the Pale of Settlement.

Individual Jews had to apply for permission to live outside of the Pale (from where we get the expression, “beyond the pale”), applications which were almost always denied. As the Russian Empire expanded, especially south into the area known as New Russia (southern Ukraine), Jews were permitted to settle in this new terrain, which included the city of Odessa. The Ukrainian port soon became the center of flourishing Jewish life, one of the major Jewish centers of the world.

Hasidism

Armenian Jew in Georgia Hasidic Jews are extremely pious and mystical ultra-Orthodox Jews known for their unusual clothing styles and preservation of 18th century customs and rituals. They are also known for their strong devotion to individual leaders, their ascetic lifestyles, ecstatic religion experiences, devotion to prayer and study and their emphasis on the traditional Jewish concept of simple delight in the service of God.

The Hasidic movement was founded in central Europe in the 18th century by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tob (Boav Shem Toyva), a mystic who lived in Medshibish Ukraine, now regarded as a great center of Hasidism. The Hasidic communities in central Europe were largely wiped out during the Holocaust. Most Hasidic Jews are found in Israel and the United States.

According to the BBC: “Poland and Central Europe saw the creation of a new Jewish movement of immense importance - Hassidism. It followed the example of the Baal Shem Tov (1700-1760) who said that you didn’t have to be an ascetic to be holy; indeed he thought that the appropriate mood for worship was one of joy. The movement included large amounts of Kabbalic mysticism as well, and the way it made holiness in every day life both intelligible and enjoyable, helped it achieve great popularity among ordinary Jews. However it also led to divisions within Judaism, as many in the religious establishment were strongly against it. In Lithuania in 1772 Hassidism was excommunicated, and Hassidic Jews were banned from marrying or doing business with other Jews. [Source: BBC]

See Separate Article: HASIDIC JEWS: HISTORY, BELIEFS, PRACTICES africame.factsanddetails.com

Little Jewish Girl in the Russian Pale, 1890

“A Little Jewish Girl in the Russian Pale” by Mary Antin (1890) reads: “The Gentiles used to wonder at us because we cared so much about religious things about food and Sabbath and teaching the children Hebrew. They were angry with us for our obstinacy, as they called it, and mocked us and ridiculed the most sacred things. There were wise Gentiles who understood. These were educated people, like Fedora Pavlovna, who made friends with their Jewish neighbors. They were always respectful and openly admired some of our ways. But most of the Gentiles were ignorant. There was one thing, however, the Gentiles always understood, and that was money. They would take any kind of bribe, at any time. They expected it. Peace cost so much a year, in Polotzk. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 243-247, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

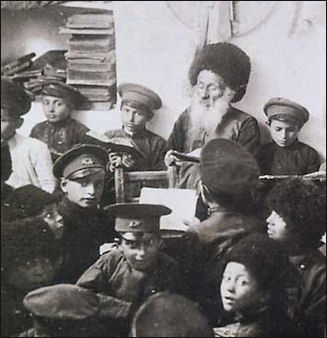

Pale teacher

“ If you did not keep on good terms with your Gentile neighbors, they had a hundred ways of molesting you. If you chased their pigs when they came rooting up your garden, or objected to their children maltreating your children, they might complain against you to the police, stuffing their case with false accusations and false witnesses. If you had not made friends with the police, the case might go to court; and there you lost before the trial was called unless the judge had reason to befriend you.

“Many bitter sayings came to your ears if you were a little girl in Polotzk. "It is a false world," you heard, and you knew it was so, looking at the czar's portrait, and at the flags. "Never tell a police officer the truth," was another saying, and you knew it was good advice. That fine of three hundred rubles was a sentence of life-long slavery for the poor locksmith, unless he could free himself by some trick. As fast as he could collect a few rags and sticks, the police would be after them.

“Perhaps I should not have had so many foolish fancies if I had not been so idle. If they had let me go to school — but of course they didn't. There was one public school for boys, and one for girls, but Jewish children were admitted in limited numbers — only ten to a hundred; and even the lucky ones had their troubles. First, you had to have a tutor at home, who prepared you and talked all the time about the examination you would have to pass, till you were scared. You heard on all sides that the brightest Jewish children were turned down if the examining officers did not like the turn of their noses. You went up to be examined with the other Jewish children, your heart heavy about that matter of your nose. There was a special examination for the Jewish candidates, of course: a nine-year-old Jewish child had to answer questions that a thirteen-year-old Gentile was hardly expected to answer. But that did not matter so much; you had been prepared for the thirteen-year-old test. You found the questions quite easy. You wrote your answers triumphantly — and you received a low rating, and there was no appeal.

“I used to stand in the doorway of my father's store munching an apple that did not taste good any more, and watch the pupils going home from school in twos and threes; the girls in neat brown dresses and black aprons and little stiff hats, the boys in trim uniforms with many buttons. They had ever so many books in the satchels on their backs. They would take them out at home, and read and write, and learn all sorts of interesting things. They looked to me like beings from another world than mine. But those whom I envied had their troubles, as I often heard. Their school life was one struggle against injustice from instructors, spiteful treatment from fellow students, and insults from everybody. They were rejected at the universities, where they were admitted in the ratio of three Jews to a hundred Gentiles, under the same debarring entrance conditions as at the high school: especially rigorous examinations, dishonest marking, or arbitrary rulings without disguise. No, the czar did not want us in the schools.”

Czar and Jews in the Russian Pale

1917.jpg)

Jews in Khorostkiv in western Ukraine in 1917 “A Little Jewish Girl in the Russian Pale” by Mary Antin (1890) reads: “ In your father's parlor hung a large colored portrait of Alexander III. The czar was a cruel tyrant — oh, it was whispered when doors were locked and shutters tightly barred, at night — he was a Titus, a Haman, a sworn foe of all Jews — and yet his portrait was seen in a place of honor in your father's house. You knew why. It looked well when police or government officers came on business. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 243-247, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“The czar was always sending us commands, — you shall not do this and you shall not do that, — till there was very little left that we might do, except pay tribute and die. One positive command he gave us: You shall love and honor your emperor. In every congregation a prayer must be said for the czar's health, or the chief of police would close the synagogue. On a royal birthday every house must fly a flag, or the owner would be dragged to a police station and be fined twenty-five rubles. A decrepit old woman, who lived all alone in a tumble-down shanty, supported by the charity of the neighborhood, crossed her paralyzed hands one day when flags were ordered up, and waited for her doom, because she had no flag. The vigilant policeman kicked the door open with his great boot, took the last pillow from the bed, sold it, and hoisted a flag above the rotten roof.

“The czar always got his dues, no matter if it ruined a family. There was a poor locksmith who owed the czar three hundred rubles, because his brother had escaped from Russia before serving his time in the army. There was no such fine for Gentiles, only for Jews; and the whole family was liable. Now the locksmith never could have so much money, and he had no valuables to pawn. The police came and attached his household goods, everything he had, including his bride's trousseau; and the sale of the goods brought thirty-five rubles. After a year's time the police came again, looking for the balance of the czar's dues. They put their seal on everything they found.”

Economic Life in the Russian Pale

“A Little Jewish Girl in the Russian Pale” by Mary Antin (1890) reads: “The cheapest way to live in Polotzk was to pay as you went along. Even a little girl understood that... Business really did not pay, when the price of goods was so swollen by taxes that the people could not buy. The only way to make business pay was to cheat — cheat the government of part of the duties. Playing tricks on the czar was dangerous, with so many spies watching his interests. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 243-247, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

Jewish money changer

“People who sold cigarettes without the government seal got more gray hairs than banknotes out of their business. The constant risk, the worry, the dread of a police raid in the night, and the ruinous fines, in case of detection, left very little margin of profit or comfort to the dealer in contraband goods. "But what can one do? " the people said, with that shrug of the shoulders that expresses the helplessness of the Pale. "What can one do? One must live."

“It was not so easy to live, with such bitter competition as the congestion of population made inevitable. There were ten times as many stores as there should have been, ten times as many tailors, cobblers, barbers, tinsmiths. A Gentile, if he failed in Polotzk, could go elsewhere, where there was less competition. A Jew could make the circle of the Pale only to find the same conditions as at home. Outside the Pale he could only go to certain designated localities, on payment of prohibitive fees, which were augmented by a constant stream of bribes; and even then he lived at the mercy of the local chief of police.

“Artisans had the right to reside outside the Pale on fulfillment of certain conditions which gave no real security. Merchants could buy the right of residence outside the Pale, permanent or temporary, on conditions which might at any time be changed. I used to picture an uncle of mine on his Russian travels, hurrying, hurrying, to finish his business in the limited time; while the policeman marched behind him, ticking off the days and counting up the hours. That was a foolish fancy, but some of the things that were done in Russia really were very funny.”

Orthodoxy and Reforms of Judaism

The Enlightenment in 17th and 18th century Europe helped free the Jews from their ghettos and opened them to the outside world and exposed them to ideas such liberalism and social equality and justice. This was a period in which Jews went through many changes and modern Judaism took shape, coalescing into it rather rigid orthodox form on the 16th to 18th centuries and reformed forms in the 19th century. It as also a time when many Jews escaped being Jews.

See Sects

There were a number of Messiah movements in this period. Perhaps the most famous was led by Sabbarai Sevi, a 17th century figure who raised the hope of the Jewish diaspora of a return to Jerusalem.

Persecution of the Jews in Eastern Europe

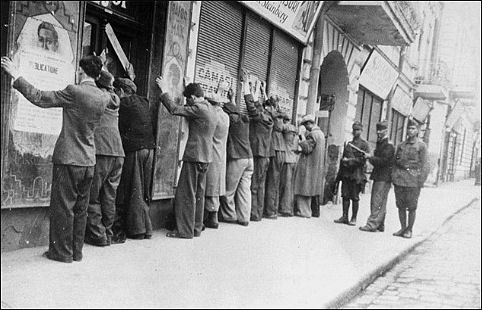

Pogrom in Bialostok in 1906

With the rise of democratization in the late 18th and 19th century the Jews were granted more freedoms. By 1870 all western and central European nations had granted the Jews the same rights as other citizens under the law.

However, persecution continued particularly in Russia, Poland and Romania, where Jews endured pogroms, ritual murders, continued confinement in ghettos and humiliations. During the pogroms of the mid 19th-century the Jewish population of some towns in central Europe and eastern Europe declined by a third.

In the 19th century prejudice against Jews was based more on ethnic and racial superiority and inferiority. Anti-Semitism was justified by racist theories.

Citizenship for Jews in the Austria-Hungary empire had strings attached and Jews were not allowed to become citizens in the North German Confederation until 1869. In Hungary, many professional Jews had assimilated. Between 1870 and World War I, many university professors in eastern Europe who were Jewish chose to hide the fact by changing their names or even getting baptized.

Pogroms in Russia

In 1882, the Russian government passed its notorious anti-Semitic “May laws” that drove Jews off their farms and forced them to live in town ghettos. Violent pogroms against the Jews erupted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a way of dealing with the "Jewish problem."

The pogroms began in during a period of repression and discontent when many people blamed their problems on the Jews. Local authorities fanned these sentiments as the Jews made convenient scapegoats. Among the peasantry Jews were regarded as money-hungry shopkeepers and capitalists. Authorities viewed them as political agitators.

Many Jews fled overseas. Others joined revolutionary organizations such as the Bolsheviks. Pogroms in tsarist Russia forced more than 2 million Jews to seek asylum in the United States between 1881 and 1914. In 1900, nearly a quarter of the new Jewish Russian arrivals in the U.S. were employed in the garment business.

There were severe anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia in 1903 and 1905-6. Vowing to "drown the revolution in Jewish blood," Russian Interior Minister Vyacheslav von Plehve sent police and gangs of anti-Semites on a three-day pogrom through the town of Kishinev. Over 60 Jews were killed or injured and 500 Jewish homes were looted or destroyed.

See Separate Article HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN RUSSIA factsanddetails.com

Pogroms and Zionism

Odessa was the site of pogroms in 1821, 1859, 1871, 1881, 1886 and 1905. There in the amid of the anti-Jewish violence, Vladimir Jabotinsky created the Jewish Self-Defense Organization, a Jewish militant group whose purpose was to protect Jews from attacks in Odessa and elsewhere in Russia. Jabotinsky believed the only way for Jews to be free from the threat of violence was to be armed — “better to have a gun and not need it than to need it and not have it!” he said. Jabotinsky became a prominent Zionist, changed his name from Vladimir to Ze’ev, and founded the Revisionist Zionist movement. Jabotinksy died in New York in 1940, before his dream of a Jewish homeland was realized, but after the establishment of the Jewish State, his remains were transferred to Israel.

Daniel Gordis wrote in Bloomberg: “At the Sixth Zionist Congress in 1903, Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, evoked Kishinev not as an event, but as a condition. “Kishinev exists wherever … (Jews’) self-respect is injured and their property despoiled because they are Jews. Let us save those who can still be saved!” The Jews, he insisted, needed a state of their own. [Source: Daniel Gordis, Bloomberg, November 2014 ++]

“He was not the first to say this. When the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881 unleashed a similar burst of murderous anti-Jewish violence, an earlier Zionist, Yehuda Leib Pinsker, wrote that “the misfortunes of the Jews are due, above all, to their lack of desire for national independence; … if they do not wish to exist forever in a disgraceful state … they must become a nation.” As long as the Jew was landless and stateless, Pinsker argued as Herzl would once again a decade and a half later, the Jew would persist in a “disgraceful state.” He, too, argued that there was no choice — the Jews needed to flee Europe. ++

“So flee they did, by the many millions. Most went to America, but some newly committed Zionists went to Palestine where they hoped to build a nation-state for the Jews. The Italians had Italy, the Poles had Poland and the Germans had Germany. Each had a language, a history, a culture. So, too, did the Jews; what they lacked was a state, and the price of that statelessness, they believed, was Kishinev.” ++

Pogrom in Ukraine

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024

.JPG)