Home | Category: Neanderthals

NEANDERTHALS

Neanderthals are named after the German valley near Dusseldorf where the first Neanderthal fossils were discovered in 1856. Neanderthals survived the Ice Age, and were the first human species to adapt to cold climates.For a period of time, Neanderthals overlapped with humans and even had sex with them. Neanderthals and closely-related Denisovans are our closest extinct relatives. Several studies have shown that most people of Eurasian descent carry between and one and four percent of Neanderthal genes in their own genome. [Sources: Stephan Hall, National Geographic, October 2008; Rick Gore, National Geographic, January, 1996]

Neanderthals are named after the German valley near Dusseldorf where the first Neanderthal fossils were discovered in 1856. Neanderthals survived the Ice Age, and were the first human species to adapt to cold climates.For a period of time, Neanderthals overlapped with humans and even had sex with them. Neanderthals and closely-related Denisovans are our closest extinct relatives. Several studies have shown that most people of Eurasian descent carry between and one and four percent of Neanderthal genes in their own genome. [Sources: Stephan Hall, National Geographic, October 2008; Rick Gore, National Geographic, January, 1996]

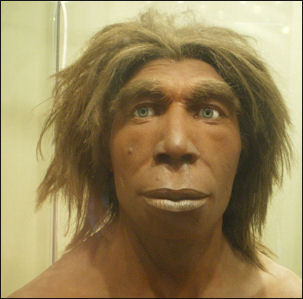

Neanderthals are thought to have evolved in Europe roughly 400,000 to 500,000 years ago, They lived in parts of Europe, Central Asia and Middle East for up to 300,000 years until they died out or where assimilated by anatomically modern humans.around 30,000 years ago. They were stockier and stronger than humans. Fossil remains of Neanderthals have allowed scientists to discern their appearance in detail. The geneticist Svante Paabo said. “We know quite well what Neanderthals look like. They were quite more robust than modern humans ... more muscular and probably more adapted to living in a harsh northerly climate.”

Geologic Age: 300,000 to 28,000 years ago. This time period is difficult to date. Too young for potassium-argon dating and too old for carbon-dating. Linkage to Modern Humans: Whether they evolved from “Homo erectus” or archaic early man or some other hominin is still a matter of debate. Most scientists believe they originated in Africa 100,000 years ago and migrated to Asia and Europe. Size: males: 1.65 meters (5 feet 4½ inches), 84 kilograms (185 pounds); females: 1.57 meters (5 feet 2 inches), (66 kilograms (145 pounds). Brain Size: Larger and just as well developed as modern humans. The skull of one specimen found in Amud, Israel had a cranial capacity of 1,740 cubic centimeters. The average modern human brain is 1,350 cubic centimeters.

A lot has been written about Neanderthals. There is a lot of anthropological, archaeological and paleontological — and even DNA data — on them, plus a lot theories about how they evolved, how they died out and what their relationship was to modern humans. In some respects they have captured our imagination more intensely than our own ancient ancestors have, perhaps because they were sort of like us but somehow weird and alien too.

Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

Neanderthal Experts: Erik Trinkhaus, Washington University in St. Louis; Portuguese archaeologist João Zilhão from the University of Barcelona; Gerd-Christian Weniger, former director of the Neanderthal Museum; Jean-Jacques Hublin, director of the Department of Human Evolution of the Max Planck Institute; Fred Smith, a Neanderthal specialist at Illinois University

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science Is Rewriting Their Story”

by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body”

by Steven Mithen (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature” by Ludovic Slimak Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

Where and When Neanderthals Lived

Neanderthals lived mainly in Europe and migrated as far south as Israel and Spain during the ice ages. Flourishing in a relatively cold ice-age climate for 200,000 years, they lived in Europe at that time when it was covered by woods and grasslands that supported large herds of horses, reindeer, bison and species adapted for cold weather. During occasional subtropical periods that lasted for around 10,000 years or less, hippos lived in the Thames and hyenas and lions roamed parts of Russia. Scientists theorize that the Neanderthals arrived from a place with a warm climate, perhaps migrating south during the winter until they adapted to the colder climate.

Neanderthal remains have been found as far east as Uzbekistan, the Altai region and Siberia as far south as Israel and Spain, as far west as England and as far north as northern Germany, the Czech Republic and the Arctic Circle of Russia Scientists estimated that even at the height of their occupation of western Europe there were never more than 15,000 of them. This conclusion was reached from DNA studies that show very little genetic diversity, a sign of a small population.

The remains of more than 400 Neanderthal individuals, including 30 relatively complete skeletons, have been found. Many specimens have been found in Germany, Italy, Spain and France. Famous discovery site include the Neander Valley, near Dusseldorf, Germany, where the first Neanderthal was discovered in 1856; La Ferrassie, France, where a complete skull was found in 1909 (Housed in Musée de l'Homme, Paris).

See Separate Article: WHERE AND WHEN NEANDERTHALS LIVED factsanddetails.com

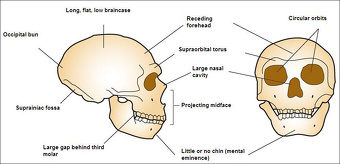

Neanderthal Skull and Face Features

Neanderthals had a large head, nose and face; heavy, bulging, boney browridge (often regarded as the hallmark of the Neanderthal skull); weak chin, protruding jaw, receding forehead and cheekbones. They lacked the strong boney chins and high foreheads of modern humans but had a broad face with a midsection thrust forward that makes their large nose look even bigger. Because their face below their eyes juts forward, their cheekbones angle to side instead of forward like modern humans.

Modern human brain cases were "higher and rounder" than those of Neanderthals. Early human brows were also much less pronounced, if not non-existent, compared to Neanderthals. CT scans reveal that human ear bones are shaped differently compared to Neanderthals. [Source: Sara Novak, Discover Magazine, April 9, 2024]

Neanderthals possessed a strong double-arched brow ridge and relatively large front teeth. They had powerful jaws and strong teeth. Based on teeth wear patterns, some scientists say that Neanderthals used their front teeth like vises or a “third hand” to hold objects they were cutting with stone tools. Some scientists have theorized their pronounced browridges ridges may have been produced by growth changes cause by living a cold environment. Neanderthals looked different enough from us that if you saw one on a subway you would not mistake him for a modern human.

Neanderthals had tall noses that could warm and moisten the cold and dry air around them in cold climates. Large sinuses adjacent to the nose gave Neanderthal upper jaws and cheeks an inflated appearance. Large external nasal passages which were too large to warm incoming air in cold climates were likely a trait inherited from more tropical ancestors. The broad noses may have helped add moisture to the dry, cold air they breathed.

Neanderthal Body Features

Early Modern humans were taller and narrower than Neanderthals and a had a less voluminous rib cage. Neanderthals could be as much as 15 centimeters (half a foot) shorter than modern humans. They were squatter with stubbier extremities, likely because they evolved in a colder part of the world compared to early humans, who did most of their evolution in Africa. [Source: Sara Novak, Discover Magazine, April 9, 2024]

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“A new body of research has emerged that’s transformed our image of Neanderthals. Through advances in archaeology, dating, genetics, biological anthropology and many related disciplines we now know that Neanderthals not only had bigger brains than homo sapiens, but also walked upright and had a greater lung capacity. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, May 2019]

Neanderthals were short limbed, thick bodied, adapted for cold weather like people in northern climates such as Lapps and Eskimos. They had Heavy bones, thick muscles and were strong and capable of endurance. Judging by their massive arm and leg bones, and general skeletal structure, the strongest Neanderthal individuals could probably lift weights of half a ton or more. Their enormous rib cages encased large lungs capable of holding large amounts of oxygen needed for high levels of activity.

The short, stocky, barrel-chested bodies of Neanderthals and their relatively short limbs helped to conserve heat in cold climates and were ideally suited for ice age conditions. "In cold climates you want to have a thick body core to retain heat and a relatively small amount of surface areas from which to lose it," Erik Trinkaus, a Neanderthal specialist told National Geographic. It has also been suggested that Neanderthals needed more energy and therefore more oxygen, so their torsos became big to make room for a larger respiratory system.

Neanderthals had wide shoulders and hips and generally had a body that was more suited for short powerful bursts of strength rather than endurance running. Sturdy, heavily-muscled limb bones evolved as a response to a demanding lifestyle. Large muscles were positioned in such a way that they provided maximum strength. Neanderthals were so strong, some scientists say, they could have butchered animals by simply tearing them from limb to limb.

A study by Fernando Ramirez Rozzi of the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris published in Nature suggests that Neanderthals grew much quicker than modern humans with Neanderthal individual’s growing very quickly during adolescence and reaching adulthood around the age of 15. The conclusion was reached by studying the wear and tear on Neanderthal teeth and comparing them to with the bones they were found with plus human bones and teeth of a similar age.

Neanderthal Hands and Feet

According to a November 2020 study Neanderthals used their hands differently than modern humans. Scientists determined they were better suited to a squeezing a spear than delicately grasping something between the thumb and forefinger. According to Business Insider: Neanderthal hands were bigger than ours, and their thumbs stuck out at a wider angle from their palms than ours do. This meant that precision grips like the ones we use when writing would have been challenging for Neanderthals. But these ancestors had powerful squeeze grips — the kind one might need to swing a hammer. [Source: Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, December 12, 2020]

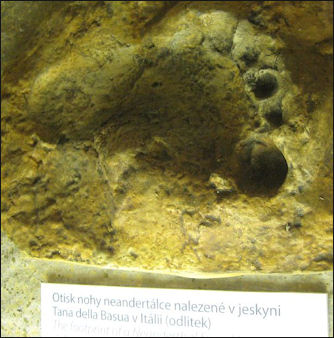

Neanderthals’ feet were broader than those of modern humans. From the size of the footprints at Le Rozel, France, where 257 footprints were found, the researchers estimated the size of the individuals who made them and then inferred their age. Some of the prints appear to have been made by a taller individual. Remains of skeletons previously suggested Neanderthals were around 150 — 160 centimeters tall, but this individual may have measured 175 centimeters (5 feet 9 inches). [Source: Kim Willsher and agencies, The Guardian, September 10, 2019]

Neanderthals Didn’t Hunch Over

Neanderthal footprint Adam Hadhazy wrote in Natural History magazine: A common misconception paints Neanderthals as stereotypical “cavemen,” hunched in their stance and gait. This depiction was borne of early anthropological work dating back over a century and exacerbated by reliance on the skeletal evidence of an elderly Neanderthal male with spinal osteoarthritis that was excavated in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France. Over the past several decades, further work has suggested that the prehistoric humans possessed an unusually straight spine, which would have made their posture precarious and unbalanced, and their walking style not-quite-human. Now a study, relying on a first-of-its-kind virtual reconstruction of a Neanderthal pelvis, indicates that Neanderthals had a curved lumbar region and neck, implying that they walked upright in the manner of modern-day Homo sapiens. [Source: Adam Hadhazy, Natural History magazine, June 2019]

“Researchers led by Martin Haeusler, head of the evolutionary morphology group at the University of Zurich, took high-precision 3D surface scans of the same well-preserved La Chapelle-aux-Saints specimen that first gave rise to the erroneous caveman posture. Because the specimen’s right hip bone was not part of its recovered remains, the team incorporated a hip bone cast into an anatomical computer simulation. They then created a computer-generated model of the specimen’s skeleton.

“The model revealed that the position of the Neanderthal’s sacrum—the shield-shaped base of the spine that connects to the pelvis—relative to the hip bone aligns with that of extant humans, pointing to similar lower back curvatures. Further evidence came from placing the lumbar and cervical vertebrae into the model. Projections off these vertebrae, called spinous processes, made close contact, indicative of spinal curvature. Finally, wear marks in the hip joint dovetailed with an upright, rather than a stooped, posture.

“Comparisons with other Neanderthal skeletons support this view of Neanderthal posture. “We show,” said Haeusler, “that there is hardly any evidence that would point to Neanderthals as having a fundamentally different anatomy than ours.”

“The researchers argue that, moving forward, Neanderthal research should focus less on the historically over-emphasized differences in anatomy that render them less “human” than Homo sapiens. Instead, subtle shifts in general human anatomies during our shared evolutionary history, as well as potential behavioral distinctions, should be grounds for gauging where we and our Neanderthal brethren ultimately went down different paths. (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences)

Neanderthal Hair and Skin

A team lead by Bruce Lahn, a researcher at the Howard High Medical Center at the University of Chicago, published a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in which he suggested that Neanderthals may have passed on a gene to modern humans that provided them with a larger brain. Lahn’s team found a gene called microcephalin (MCPH1) that regulates brain size and appears to have entered the human lineage about 1.1 million years and has a modern form that appeared about 37,000 years ago — just before Neanderthals went extinct — evidence that is circumstantial at best.

Using DNA taken from the bones of two Neanderthals, whose remains were found in Italy and Spain, a team led by Michael Hofreiter of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, determined that some Neanderthals had red hair and light skin, and possibly freckles, a view consistent with the idea that as they migrated northward Neanderthals benefits from light skin to enhance their ability to make vitamin D from sunlight.

The finding was made by examining the MC1R gene, which affects the balance red-yellow and black-brown pigments in the skin. The two Neanderthal specimens had identical mutations in their MC1R genes, which tests indicated would have produced light skin and red hair if inherited from both parents. The MC1R found in Neanderthals is different that the version found in human, suggesting the two species developed the trait independently.

Neanderthals, Dim-Witted Brutes or Intelligent as Humans?

In the past, Neanderthals were regarded as dim-witted creatures incapable of creating art or developing sophisticated tools. Recent discovers, however, have shown that Neanderthals did in fact create art and develop advanced tools as well as hunt in organized groups, care for the sick and aged and perform rituals that may have had a spiritual component. Furthermore they may have had a primitive language.

In the past, Neanderthals were regarded as dim-witted creatures incapable of creating art or developing sophisticated tools. Recent discovers, however, have shown that Neanderthals did in fact create art and develop advanced tools as well as hunt in organized groups, care for the sick and aged and perform rituals that may have had a spiritual component. Furthermore they may have had a primitive language.

"Neanderthals were highly resourceful, highly intelligent creatures," Fred Smith, a Neanderthal specialist at Illinois University, told National Geographic. "They were not big, dumb brutes by any stretch of the imagination. They were us — only different." In recent years, researchers have discovered that Neanderthals used sophisticated bone tools, buried their dead, took care of their elders, used fire, produced cave art and engravings and maybe even adorned themselves with feathers.

Christopher Stringer of the Natural History Museum of London wrote in the Times of London, “Their braincases were big, but long and low, with a large browridge instead of the domed forehead of modern humans...We cannot be certain about how intelligent they were but the Neanderthals were capable hunters, gatherers and toolmakers. While it does not seem they were great innovators, during the final 30,000 years of their existence they started to make more advanced tools, showed increasing use of pigments and developed production of jewelry.”

Neanderthal Brains

AFP reported: “Neanderthals are known to have had much larger skulls than people do today, and possibly larger brains, although this did not necessarily make them smarter. But little is known about how Neanderthals became this way. One theory is that they grew up faster – that Neanderthal children reached adult size more quickly than we do. “Previous studies suggesting this path have relied mainly on dental clues. [Source: Agence France-Presse September 22, 2017 /*]

“The latest study is based on a more complete specimen. The Neanderthal child’s skeleton included 36 percent of his left side and parts of his skull along with baby and adult teeth. After studying his remains, researchers believe that instead of simply outpacing contemporary people in brain growth, Neanderthals may have grown up over a longer period of time. “One mechanism of growing a larger brain would be expanding the period of growth,” Antonio Rosas, chairman of the Paleoanthropology Group at Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, said. /*\

Rosas “also questioned the comparison to modern humans, since different rates of brain growth are common across various people and time periods. “Furthermore, assessments of Neanderthal brain size could be skewed high, because most of the specimens paleoanthropologists have belonged to males, who were physically larger than females. This may lead us to believe Neanderthals were bigger on average than they actually were, he added. “Therefore, trying to derive much meaning from small skull size differences might be a fruitless endeavour when the bigger picture is clear. “Neanderthal brain growth may or may not be like any human population, but surely seems to fit within the normal human range,” Milford Wolpoff, professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan, said. /*\

Neanderthal Hearing

The team compared the two hominin groups’ hearing with that of chimpanzees and modern humans. Some previous studies had shown that chimpanzees are able to hear a narrower range of frequencies than humans. Other studies have demonstrated that early human ancestors belonging to the genus Australopithecus, who lived more than two million years ago, had auditory abilities similar to chimpanzees.

Conde-Valverde’s study shows that the Sima de los Huesos hominins could hear a broader frequency range than australopithecines. However, they could not hear as wide a range of sounds as their Neanderthal descendants, who could hear nearly as well as modern humans. These results imply that Neanderthals, who last shared a common ancestor with modern humans about 500,000 years ago, were likely developing spoken languages and the hearing necessary to understand them in parallel with early Homo sapiens. “We arrive at the same point,” says Conde-Valverde, “but along two different evolutionary paths.”

Neanderthal’s Massive Eyes Might Have Led To Their Extinction

Paul Jongko wrote in Listverse: “Neanderthals have larger eyes than modern humans. This fact led Eiluned Pearce of the University of Oxford to suggest that the massive eyes of Neanderthals might have caused their demise. Pearce believes that the big eyes meant that a large part of the Neanderthal’s brain was devoted to vision and body control, leaving less brain to deal with other functions, like social networking. [Source: Paul Jongko, Listverse, May 14, 2016]

“When our extinct cousins faced big problems like climate change and competition from their human contemporaries, they were severely disadvantaged. Hypothetically, had the Neanderthals possessed the ability to form complex social networks, they could have possibly survived the catastrophes that led to their extinction.

“Not all scientists are convinced with Pearce’s theory and have even contradicted it. One of them is John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Together with his colleagues, Hawks examined 18 living primate species, and he discovered that “big eyes actually indicate bigger social groups.” Hawks asserts that the size of the eyes has nothing to do with the formation of social networks. Furthermore, he believes that the reason why Neanderthals had bigger eyes is that they were slightly larger than our ancient ancestors, and that their eyes had to be proportional to their bodies.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024