Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes / Culture, Literature and Sports

GRAFFITI IN THE ROMAN ERA

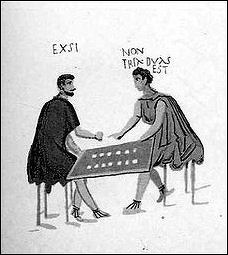

Graffiti — mainly in the form of inscriptions, chiseled messages and writings left upon the walls of buildings — at Pompeii and other sites in the Roman Empire provide some remarkable and enlightening evidences of the ordinary life of the townsmen. Some of these writings hardly rise above the dignity of mere scribblings. They are most numerous upon the buildings in those places frequented by the crowds. There we find advertisements of public shows, memoranda of sales, cookery receipts, personal lampoons, love effusions, and hundreds of similar records of the common life of this ancient people. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Describing the impression one gets of Romans by reading their graffiti, Heather Pringle wrote in Discover magazine, “The world revealed is at one tantalizingly, achingly familiar, yet strangely alien, a society that both closely parallels our own in its heedless pursuit of pleasure and yet remains starkly at odds with our cherished value of human rights and dignity."

On inscribed graffiti at Pompeii, the historian William Stearns Davis wrote: “There are almost no literary remains from Antiquity possessing greater human interest than these inscriptions scratched on the walls of Pompeii (destroyed 79 A.D.). Their character is extremely varied, and they illustrate in a keen and vital way the life of a busy, luxurious, and, withal, tolerably typical, city of some 25,000 inhabitants in the days of the Flavian Caesars. Most of these inscriptions carry their own message with little need of a commentary. Perhaps those of the greatest importance are the ones relating to local politics. It is very evident that the so-called "monarchy" of the Emperors had not involved the destruction of political life, at least in the provincial towns. [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 260-265]

Inscriptions from Pompeii with some words of wisdom: 1) “The smallest evil if neglected, will reach the greatest proportions.” 2) “If you want to waste your time, scatter millet and pick it up again.”

See Separate Articles: COMMUNICATIONS IN ANCIENT ROME: POSTAL SERVICE, SOCIAL MEDIA, SIGNALS europe.factsanddetails.com ; PROPAGANDA IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Graffiti in Antiquity” by Peter Keegan (2014) Amazon.com;

“By Roman Hands: Inscriptions and Graffiti for Students of Latin (English and Latin Edition) by Matthew Hartnett (2012) Amazon.com;

“Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii”

by Kristina Milnor (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Alexamenos Graffito: An Early Roman Commentary on Christians and Christianity”

by Thomas R. Young (2025) Amazon.com;

Ancient Peoples in their Own Words: Ancient Writing from Tomb Hieroglyphs to Roman Graffiti” by Michael Kerrigan (2019) Amazon.com;

“Graffiti in the Athenian Agora” by Mabel Lang (1988) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Graffiti in Context” (Routledge) by Jennifer Baird and Claire Taylor (2010) Amazon.com;

“Inscriptions in the Private Sphere in the Greco-Roman World” by Rebecca Benefiel and Peter Keegan (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Lives: Ancient Roman Life” Illustrated by Latin Inscriptions, by Brian K. Harvey (Author) Amazon.com;

“Children and Everyday Life in the Roman and Late Antique World”

by Christian Laes and Ville Vuolanto (2016) Amazon.com;

“Writing on the Wall: Graffiti and the Forgotten Jews of Antiquity” by Karen B. Stern (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Catacombs: The History and Legacy of Ancient Rome’s Most Famous Burial Grounds” by Charles River Editors (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Catacombs” by Rev. James Spencer Northcote (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Catacombs: Themes of Deliverance in the Age of Persecution”

by Gregory S Athnos (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Christian Catacombs of Rome: History, Decoration, Inscriptions”

by Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, et al. (2006)

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Pompeii Graffiti

Adrienne LaFrance wrote in The Atlantic: “The oldest known graffiti at Pompeii also happens to be among the simplest: Gaius was here. Or, more precisely, “Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here,” along with a time stamp, which historians have dated to October 3, 78 B.C. It’s a classic. Literally—as in, it is an artifact from classical antiquity—but it’s also a classic in the larger category of Things People Write on Walls. So-and-so was here (see also: Kilroy) has been one of the messages humans have scrawled, etched, and eventually Sharpied and spray painted onto public spaces for millennia. [Source: Adrienne LaFrance, The Atlantic, Mar 29, 2016 |^|]

Pompeii graffiti

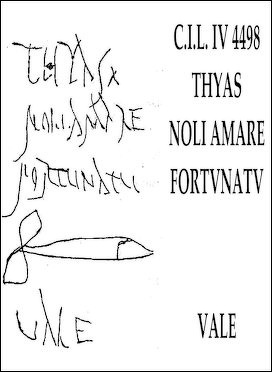

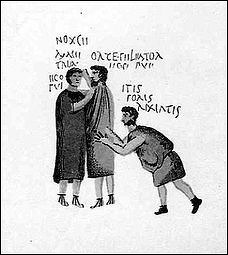

“Much of the graffiti at Pompeii seems surprisingly modern this way. Ancient inscriptions include declarations of love (“Health to you, Victoria, and wherever you are may you sneeze sweetly.”); insults (“Sanius to Cornelius: Go hang yourself!”); and remembrances (“Pyrrhus to his chum Chias: I’m sorry to hear you are dead, and so, goodbye!”). There are also billboard-esque painted inscriptions that included political campaign messages, advertisements for Gladiatorial games, and other public notices—like the equivalent of a giant flyer for a lost horse. The commonplace nature of these inscriptions is part of what makes them so historically valuable. |^|

““It recreates the life of the town,” said Rebecca Benefiel, a professor of classics at Washington and Lee University. “It’s the voices of the people who were standing there, and thinking this, and writing it. That’s why the graffiti are just so special and so enthralling.” Ancient graffiti in Pompeii, in the style typical for a political campaign. (Mirko Tobias Schäfer / Flickr) |^|

“Scholars can tell, for instance, that a tavern was once beyond the wall where a welcoming greeting—“Sodales, avete,”—can still be read. Some graffiti describes how many tunics were sent to be laundered, while other inscriptions mark the birth of a donkey and a litter of piglets. People scribbled details of various transactions onto the walls of Pompeii, including the selling of slaves. They also shared snippets of literature (lines from The Aeneid were popular) and succinct maxims like, “The smallest evil, if neglected, will reach the greatest proportions.”|^|

“And then there was the trash talk. “One speaks of ‘sheep-faced Lygnus, strutting about like a peacock and giving himself airs on the strength of his good looks,’” the London-based magazine Chambers’s Journal wrote, in 1901, of Pompeii’s well-preserved insults. “Another exclaims: ‘Epaphra glaber es,’ (Oh, Epaphras, thou art bald;) Rusticus est Cordyon, (Corydon is a clown or country bumpkin;) Epaphra, Pilicrepus non es, (Oh, Epaphras, thou art no tennis-player.)” |^|

“The fact that we can read the original inscriptions at all today is part-tragedy, part-miracle. Like most of what scholars know of Pompeii, the city’s extensive graffiti is so well preserved because it spent nearly 1,500 years entombed in ash after the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. People have been fixated on the ancient etchings since Pompeii was rediscovered centuries ago. “Though nearly 20 centuries old, the thoughtless school-boy’s scrawls, the love-sick gallant’s doggerel, or the caricature of some friend, foe, or popular favorite, are still as clear as though executed by an idler yesterday,” The New York Times wrote in 1881. |^|

Pompeii’s Graffiti as a Form of Social Media

Adrienne LaFrance wrote in The Atlantic: “All of which is somewhat sophomoric, but certainly isn’t outdated per se. The social nature of ancient graffiti, including walls where there were clusters of inscriptions featuring people writing back and forth to one another, evokes social communication of the modern era: Facebook and Twitter, for instance. “I will say that the graffiti at Pompeii are nicer than the types of things we write today, though,” Benefiel told me. [Source: Adrienne LaFrance, The Atlantic, Mar 29, 2016 |^|]

political graffiti from Pompeii

“That may be because many of the tropes associated with writing in public are by now so familiar that simply declaring “Claudius was here,” isn’t enough—in the digital space, anyway—to achieve what many people are aiming for. “Overall, people want to write on things to be known,” Roger Gastman, the author of The History of American Graffiti, told me in an email. “To be everywhere at once yet nowhere at all.” |^|

“But the wall-politicking that takes place on Facebook may be inherently different from graffiti in the physical world—even if it stems from the same basic human inclinations. “Writing your name on a [physical] wall is both a way of getting noticed but it’s also somewhat transgressive,” said Judith Donath, the author of The Social Machine: Designs for Living Online. But in order to get noticed online, where everyone can and is supposed to write on walls, you have to do more than mark down your own name and the date. The pressure, then, is to be more provocative, Donath told me. And an arms race for provocation in a world where there are more than 7,000 tweets published every second tends to debase civility pretty quickly. |^|

““Especially Twitter,” Donath said. “If you’re not saying something, it’s like you’re not there at all; you don’t exist. You have to maintain your presence there. It’s more of a temporal issue, whereas in a city it’s more spatial.” |^|

“The ancient graffiti of Pompeii brings together these two domains, the spatial and the temporal, anchoring the ideas of a group of people in time to the physical space they occupy. Few artifacts are able to do this. Books and stone tablets, for example, aren’t typically preserved in situ. Which means the preservation of the convergence in Pompeii is remarkably rare, and made all the more astonishing for the fact that much of the graffiti there dates to sometime in the twilight decades of the city’s existence. |^|

““You can walk through the entire town. You can peek into each house. You can get a sense that, wow, this is a space where people lived surrounded by color and imagery and decoration,” Benefiel said. “But I think what all of those elements give you is the space of the town. Then we have many inscriptions that are people’s names. We have hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of inscriptions that are friends writing greetings to each other. The graffiti immediately brings you to the people of the town.The graffiti really evoke the people who lived there.” |^|

Graffiti From Aphrodisias

Graffiti messages have been discovered and deciphered in the ancient city of Aphrodisias, in present-day Turkey, revealing what life was like there in Roman times. "Hundreds of graffiti, scratched or chiseled on stone, have been preserved in Aphrodisias — more than in most other cities of the Roman East(an area which includes Greece and part of the Middle East)," said Angelos Chaniotis, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton New Jersey.

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: “The graffiti touches on many aspects of the city's life, including gladiator combat, chariot racing, religious fighting and sex. The markings date to a time when the Roman and Byzantine empires ruled over the city. “"Graffiti are the products of instantaneous situations, often creatures of the night, scratched by people amused, excited, agitated, perhaps drunk. This is why they are so hard to interpret," Chaniotis said. "But this is why they are so valuable. They are records of voices and feelings on stone." [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 15, 2015]

“The graffiti includes sexual imagery, with one plaque showing numerous penises. "A plaque built into the city wall has representations of phalluses of various sizes and positions and employed in a variety of ways," Chaniotis said.

Graffiti on Love, Sex and Chariot Racing

Many pieces of love-related graffiti seem to have been written by love-struck young men. “Girl," reads an inscription found in a Pompeii bedroom, “you're beautiful I've been sent to you by one who is yours." Others express missing a loved one in timeless fashion. “Vibius Restitutus slept here alone, longing for Urbana." Others expressed urgency. “Driver," one said. “If you could feel the fires of love, you would hurry more to enjoy the pleasures of Venus. I love a younger charmer, please spur on the horses, let's get on."

Men often boasted of their love-making adventures on the walls of baths and other public buildings. Graffiti scrawled on the wall of a Pompeii bar claimed: 'I fucked the landlady.' Graffiti was often filled with bawdy and graphic details. The writers were not shy about naming names and even saying the time and place that encounters took place. Men who preferred men seemed just as emboldened to list their conquests and as men who preferred women.

On Roman-era graffiti found at Aphrodisias in present-day Turkey, Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: “The city had three chariot-racing clubs competing against each other, records show. “The south market, which included a public park with a pool and porticoes, was a popular place for chariot-racing fans to hang outthe graffiti shows. It may be "where the clubhouses of the factions of the hippodrome were located — the reds, the greens, the blues," said Angelos Chaniotis, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton New Jersey, referring to the namesof the different racing clubs. The graffiti includes boastful messages after a club won and lamentations when a club was having a bad time. "Victory for the red," reads one graffiti; "bad years for the greens," says another; "the fortune of the blues prevails," reads a third. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 15, 2015]

Graffiti Related to Gladiators

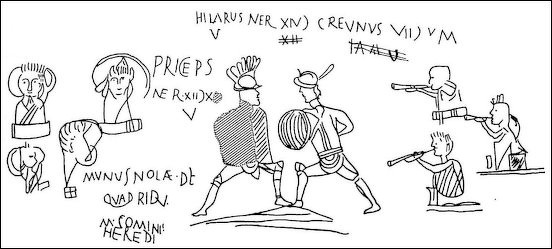

Many of the graffiti inscriptions in Pompeii are related to gladiators, such as one from A.D. 1st century that indicates the outcome of a match between gladiators Severus and Albanus Many of them announce upcoming events. “Twenty pairs of gladiators provided by Quintus Monnius Rufus are to fight at Nola May First, Second, and Third, and there will be a hunt.” There are virtually no accounts written by gladiators themselves presumably at least in part because few of them could read or write. Not even Spartacus, the most famous of all gladiators, spoke for himself. Most of what we know about gladiators is based on descriptions by Roman historians and writers, Roman-era images (many of them mosaics), and bits and shreds of archaeological evidence. A surprising amount of transportation has been gleaned from Roman-era graffiti.

Natasha Sheldon wrote in ancienthistoryarchaeology.com: “Graffiti and other archaeological evidence tell us a great deal about the lives and life expectancy of Roman gladiators in Pompeii. Despite the Pompeian’s appetite for blood, their life expectancy was not as low as one would expect. In the main, gladiators were slaves purchased for their strength by local businessmen. They were trained in troupes and then hired them out to fight in the games. Many gladiators had single names like ‘Princeps’ and 'Hilarius’ which indicated that they were slaves. Some gladiators were also free. The gladiator Lucius Raecius Felix was probably a freedman. Felix was a common slave name and his other two names were probably adopted from his former master’s name and added after his freedom. Some gladiators were also freeborn. Graffiti in Pompeii records the name of a gladiator Marcus Attilius. His name is not that of a slave and does not indicate he was a freedman, suggesting he signed up to the arena for profit. [Source: Natasha Sheldon, ancienthistoryarchaeology.com]

Professor Kathleen Coleman of Harvard University wrote for the BBC: “Regardless of their status, gladiators might command an extensive following, as shown by graffiti in Pompeii, where walls are marked with comments such as Celadus, suspirium puellarum ('Celadus makes the girls swoon'). Indeed, apart from the tombstones of the gladiators, the informal cartoons with accompanying headings, scratched on plastered walls and giving a tally of individual gladiators' records, are the most detailed sources that modern historians have for the careers of these ancient fighters. [Source: Professor Kathleen Coleman, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Sometimes these graffiti even form a sequence. One instance records the spectacular start to the career of a certain Marcus Attilius (evidently, from his name, a free-born volunteer). As a mere rookie (tiro) he defeated an old hand, Hilarus, from the troupe owned by the emperor Nero, even though Hilarus had won the special distinction of a wreath no fewer than 13 times. |::|

“Attilius then capped this stunning initial engagement (for which he himself won a wreath) by going on to defeat a fellow-volunteer, Lucius Raecius Felix, who had 12 wreaths to his name. Both Hilarus and Raecius must have fought admirably against Attilius, since each of them was granted a reprieve (missio). |::|

Gladiator Graffiti From Aphrodisias

Hundreds of graffiti messages engraved into stone in the ancient city of Aphrodisias, in modern-day Turkey, have been discovered and deciphered, more than in most other cities of the Roman East (an area which includes Greece and part of the Middle East)." Many of the inscriptions rale to gladiators.

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: “The graffiti also includes many depictions of gladiators. Although the city was part of the Roman Empire, the people of Aphrodisias mainly spoke Greek. The graffiti is evidence that people living in Greek-speaking cities embraced gladiator fighting, Chaniotis said. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 15, 2015]

Angelos Chaniotis, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton New Jersey, said a lecture at Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum: “"Pictorial graffiti connected with gladiatorial combat are very numerous," he said. "And this abundance of images leaves little doubt about the great popularity of the most brutal contribution of the Romans to the culture of the Greek east."

““Some of the most interesting gladiator graffiti was found on a plaque in the city's stadium where gladiator fights took place. The plaque depicts battles between two combatants: a retiarius (a type of gladiator armed with a trident and net) and a secutor (a type of gladiator equipped with a sword and shield). One scene on the plaque shows the retiarius emerging victorious, holding a trident over his head, the weapon pointed toward the wounded secutor. On the same plaque, another scene shows the secutor chasing a fleeing retiarius. Still another image shows the two types of gladiators locked in combat, a referee overseeing the fight.

“"Probably a spectator has sketched scenes he had seen in the arena," Chaniotis said. The images offer "an insight (on) the perspective of the contemporary spectator. The man who went to the arena in order to experience the thrill and joy of watching — from a safe distance — other people die."

Pompeii Inscriptions and Graffiti About Politics and Elections

Some inscriptions and graffiti about politics and elections from Pompeii: “The dyers request the election of Postumius Proculus as Aedile.” [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 260-265]

“Vesonius Primus urges the election of Gnaeus Helvius as Aedile, a man worthy of pubic office.”

“Vesonius Primus requests the election of Gaius Gavius Rufus as duumvir, a man who will serve the public interest — do elect him, I beg of you.”

“Primus and his household are working for the election of Gnaeus Helvius Sabinus as Aedile.”

“Make Lucius Caeserninus quinquennial duumvir of Nuceria, I beg you: he is a good man.”

“His neighbors request the election of Tiberius Claudius Verus as duumvir.”

“The worshipers of Isis as a body ask for the election of Gnaeus Helvias Sabinus as Aedile.”

“The inhabitants of the Campanian suburb ask for the election of Marcus Epidius Sabinus as aedile.”

“At the request of the neighbors Suedius Clemens, most upright judge, is working for the election of Marcus Epidius Sabinus, a worthy young man, as duumvir with judicial authority. He begs you to elect him.”

“The sneak thieves request the election of Vatia as Aedile.

Graffiti Reflects Competition Between Religions in the Roman World

On Roman-era graffiti found at Aphrodisias in present-day Turkey, Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Graffiti was one way in which religious groups “competed. Archaeologists have found the remains of statues representing governors (or other elite persons) who supported polytheistic beliefs. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 15, 2015]

"Christians had registered their disapproval of such religions by carving abbreviationson the statues thatmean"Mary gives birth to Jesus," refuting the idea that many gods existed. Christians, Jews and a strong group of philosophically educated followers of the polytheistic religions competed in Aphrodisias for the support of those who were asking the same questions: Is there a god? How can we attain a better afterlife?" said Angelos Chaniotis, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton New Jersey, told Live Science.

“Those who followed polytheistic beliefs carved graffiti of their own. "To the Christian symbol of the cross, the followers of the old religion responded by engraving their own symbol, the double axe," said Chaniotis, noting that this object was a symbol of Carian Zeus (a god), and is seen on the city's coins. Aphrodisias also boasted a sizable Jewish population. Many Jewish traders set up shop in an abandoned temple complex known as the Sebasteion.

“Among the graffiti found there is a depiction of a Hanukkah menorah, a nine-candle lamp that would be lit during the Jewish festival. "This may be one of the earliest representations of a Hanukkah menorah that we know from ancient times," said Chaniotis.

“Most of the graffiti Chaniotis recorded dates between roughly A.D. 350 and A.D. 500, appearing to decline around the time Justinian became emperor of the Byzantine Empire, in A.D. 527. In the decades that followed, Justinian restricted or banned polytheistic and Jewish practices. Aphrodisias, which had been named after the goddess Aphrodite, was renamed Stauropolis. Polytheistic and Jewish imagery, including some of the graffiti, was destroyed.”

Ancient Roman Graffiti Shows the Novelty of Early Christianity

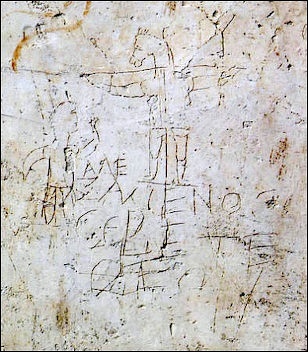

Christian graffiti

Professor Wayne A. Meeks told PBS: “One of the major implications that we get from this material in the early second century such as the letters of Pliny describing the Christians is that the Christians at this stage are still something new, something novel from the perspective of the Romans. The Romans don't really know quite what to make of them. They're odd. They sort of look like Jews. The Christians don't do certain things but they really don't know what they believe and what they stand for and why they're different. They're just different. They're foreign. [Source: Wayne A. Meeks, Woolsey Professor of Biblical Studies Yale University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“[W]e have a good example of this kind of pagan perspective on Christians from a little graffiti found in Rome from the Palatine Hill. It shows a man hanging on a cross and below it is an inscription scratched very crudely into the wall.... It's quite literally graffiti in the modern sense of the term and it says Alexamenos worships his god. In the picture we see Alexamenos bowing down before the man on the cross, but the unusual thing is that the man on the cross has the head of a donkey. From the perspective of these pagans there was this unusual belief attached to Christianity. They're worshipping a crucified man, that in of itself is probably something that they would have thought odd, and secondly the identity of this crucified man is somehow confused with animal deities... some sort of peculiar half animal, half man person. The pagans really don't know quite what to do with all this.

“Even if we hear a fair amount of pagan attack on Christianity as stupid or criminal and we do know that some persecutions occur, we shouldn't necessarily assume that all Christians were against the Roman government, were marginal parts of society. In many cases, Christians did participate in social activities and were good citizens. Indeed the Christians often claim, "We are the most ethical part of your empire. We behave better than the rest of you. Why would you want to persecute us?"”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024