Home | Category: Roman Empire and How it Was Built / Ethnic Groups and Regions

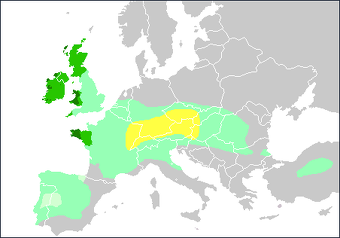

EUROPEAN PROVINCES OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Portrait of a Barbarian bust, AD 3rd century

1) Western.

Spain (205-19 B.C.).

Gaul (France, Belgium, parts of Germany, 120-17 B.C.).

Britain (A.D. 43-84).

2) Central.

Rhaetia et Vindelicia (roughly Switzerland, northern Italy15 B.C.).

Noricum (Austria, Slovenia, 15 B.C.).

Pannonia (western Hungary, eastern Austria, northern Croatia, north-western Serbia, northern Slovenia, western Slovakia and northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. A.D. 10).

3) Eastern.

Illyricum (northern Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and coastal Croatia, 167-59 B.C.).

Macedonia (northern Greece, modern Macedonia, 146 B.C.).

Achaia (western Greece, 146 B.C.).

Moesia (Central Serbia, Kosovo, northern modern Macedonia, northern Bulgaria and Romanian Dobrudja 20 B.C.).

Thrace (northeast Greece, A.D. 40).

Dacia (Romania, A.D. 107). \~\

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Romans and Barbarians: Four Views from the Empire's Edge” by Derek Williams (1968) Amazon.com;

“Barbarians in the Greek and Roman World” by Erik Jensen (2018) “Empires and Barbarians” by Peter Heather Amazon.com;

href="https://amzn.to/42q79z1"> Amazon.com;

“The Roman Barbarian Wars I: The Era of Roman Conquest ” by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Barbarian Wars II: Tiberius to Trajan” by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck (2025) Amazon.com;

“Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376 - 568" by Guy Halsall (2008) Amazon.com;

“Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity” by Ralph W. Mathisen and Danuta Shanzer (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Enemies of Rome: The Barbarian Rebellion Against the Roman Empire” by Stephen Kershaw (2021) Amazom.com

“Rebels Against Rome: 400 Years of Rebellions Against the Rule of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins ((2023) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“Race and Ethnicity in the Classical World: An Anthology of Primary Sources in Translation” by Rebecca F. Kennedy , C. Sydnor Roy, et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cultural Identity in the Roman Empire” by Joanne Berry, Ray Laurence (2002) Amazon.com;

“Demography and the Graeco-Roman World: New Insights and Approaches”

by Claire Holleran and April Pudsey (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Provinces of the Roman Empire, from Caesar to Diocletian (Volume 1)”

by Theodor Mommsen and William P Dickson Amazon.com;

“The Provinces of the Roman Empire, from Caesar to Diocletian (Volume 2)”

by Theodor Mommsen and William P Dickson Amazon.com;

“Law in the Roman Provinces (Oxford Studies in Roman Society & Law)

by Kimberley Czajkowski, Benedikt Eckhardt, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

"Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World"

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“The Roman World 44 BC-AD 180 (Routledge) by Martin Goodman (2013)

Amazon.com;

“Migration and Mobility in the Early Roman Empire” by Luuk de Ligt and Laurens Ernst Tacoma (2016) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

Greeks Versus 'Barbarians'

Dr Neil Faulkner wrote for the BBC: “In the east, change was limited. Here, long before, urban civilisation had taken root and for some centuries this had been of a distinctively Greek (or 'Hellenistic' character). Though the Romans had once caricatured the Greeks as effete and decadent, this was changing by the late first century AD. The Romans increasingly admired and imitated Greek cultural achievement. [Source: Dr Neil Faulkner, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The change is symbolised in imperial portraits. Unlike their clean-shaven predecessors, second century emperors, starting with Hadrian (117 - 138 AD) sported the Greek-style beards of 'philosopher-kings'. |In fact, so far from the east being Romanised, it was more a case of the west being Hellenised. A uniform elite culture that was both Roman and Greek was thereby forged. This became the developed language of rank, status and 'good taste' in the Roman empire's golden age. |::|

“In the western provinces, on the other hand, there was often a sharp contrast between traditional native culture and Roman innovations. |In Spain, France, Belgium and Britain, for example - all areas with a strongly Celtic culture - the archaeology of the Roman period looks very different from that of the preceding Iron Age: Rectangular houses instead of round ones; towns with regular street-grids instead of hilltop enclosures curling round the contours; mosaics, frescoes and naturalistic sculptures instead of wooden idols, golden torcs and enamelled bronzework. “

Hercynian Forest

The was an ancient and dense forest that stretched across Western Central Europe, from Northeastern France to the Carpathian Mountains, including most of Southern Germany, though its boundaries are a matter of debate. It formed the northern boundary of that part of Europe known to writers of Antiquity. [Source Wikipedia]

Tacitus (A.D. 56–120) wrote: “The Hercynian forest extends over an area which a man travelling f dits without encumbrance requires nine days to traverse. There is no other way of defining its extent, and the natives have no standards of measurement. Starting from the frontiers of the Helvetii, Nemetes, and Rauraci, it extends right along the line of the Danube to the frontiers of the Dacians and Anartes; then, bending to ~ the left and passing through a country remote / fiom the river, it borders (so vast is its extent) upon the territories of many peoples; and no one in Western Germany can say that he has got to the end of the forest, even after travelling right on for sixty days, or has heard whereabouts it begins. It is known to produce many kinds of Wild animals which have never been seen elsewhere. The follolving, on account of their strongly marked characteristics, seem worthy of mention.

“There is a species of ox, shaped like a stag, With a single horn standing out between its ears from the middle of its forehead, higher and straighter than horns as we know them. Tines spread out wide from the top, like hands and branches. The characteristics of the male and the female are identical, and so are the shape and size of their horns.

Gauls

“Again, there are elks, so-called, Which resemble goats in shape and in having piebald coats, but are rather larger. They have blunt horns, and their legs have no knots or joints' They do not lie down to sleep; and if by any chance they are knocked down, they cannot stand up again, or even raise themselves. Their resting-places are trees, against which they lean and thus rest in a partially recumbent position. Hunters mark their usual lair from their tracks and uproot or cut deep into all the trees in the neighbourhood, so that they just look as if they 53 B.C. were standing. The animals lean against them as usual, upset the weakened trunks by their mere weight, and fall down along with them.

“There is a third species, called aurochs, a little smaller than elephants, having the appearance, colour, and shape of bulls. They are very strong and swift, and attack every man and beast they catch sight of. The natives sedulously trap them in pits and kill them. Young men engage in the sport, hardening their muscles by the exercise; and those who kill the largest head of game exhibit the horns as a trophy, and thereby earn high honor. These animals, even when caught young, cannot be domesticated and tamed. Their horns, in size, shape, and appearance, differ widely from those of our oxen. The natives, who are fond of collecting them, mount them round the rim with silver and use them as drinking-cups at grand banquets.

Gaul (France) and Gauls

Gaul was a region of Western Europe initially defined by the Romans. Comprising present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of 494,000 square kilometers (191,000 square miles). Julius Caesar divided Gaul into three parts: Gallia Celtica, Belgica, and Aquitania. [Source Wikipedia]

The Romans ruled Gaul for more than 500 years. They annexed Provence in 121 B.C. and subdued the Gauls during the Gallic Wars under Caesar between 57 and 52 B.C. Gaul became part of the Roman empire when Caesar defeated Vercingetorix in 52 B.C. The first assembly of Gauls was held in A.D. 12. Gaul (France) remained Roman until the Western Roman Empire disintegrated into small-scale agrarian settlements as the Franks invaded in the fifth century A.D.

The Romans founded numerous cities and towns that remain today, including Arles, Lyon, Autun, Frejus, Orange, Nimes and Narbonne. Before their division the Goths were allowed by the Romans to settle within the borders of the Roman Empire. They rose against the Romans and killed the Roman emperor Valentinian in battle. His successor was Theodosius sued for peace.

The Gauls lived in extreme northern Italy and the areas now occupied by France and Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Crossing the Alps from western Europe, they had pushed back the Etruscans and occupied the plains of the Po; hence this region received the name which it long held, Cisalpine Gaul. They held this territory against the Ligurians on the west and the Veneti on the east; and for a long time were the terror of the Italian people. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

See Separate Article: FRANCE (GAUL) IN THE ANCIENT ROMAN ERA europe.factsanddetails.com

Celts and Germanic Tribes

The Celts were a group of related tribes, linked by language, religion and culture, that gave rise to the first civilization north of the Alps. They emerged as a distinct people around the 8th century B.C. and were known for their fearlessness in battle. Pronouncing Celts with a hard "C" or soft "C" are both okay. American archeologist Brad Bartel called the Celts "the most important and wide-ranging of all European Iron Age people." English speakers tend to say KELTS. The French say SELTS. The Italian say CHELTS. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1977]

The origin of the Celts remains a mystery. Some scholars believe they originated in the steppes beyond the Caspian Sea. They first appeared in central Europe east of the Rhine in the seventh century B.C. and inhabited much of northeast France, southwest Germany by 500 B.C. They crossed the Alps and expanded into the Balkans, north Italy and France around the third century B.C. and later they reached the British isles. They occupied most of western Europe by 300 B.C.

Germanic tribes are usually identified as a completely independent people from the Celts but in fact they are closely related.The distinction between Gauls (Celts) and Germanic tribes can be traced back to Julius Caesar who decided that Gaul region was worth conquering and the Germanic region to north wasn't.

See Separate Article: CELTS, ANCIENT ROMANS AND GERMANIC TRIBES IN NORTHERN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

Spain in the Roman Era

When Rome defeated Carthage in the Punic Wars in 146 B.C. it took over Carthage's territories in Spain. The wealth brought in from Spain enabled Rome to finance the conquests of Rome. Even so the Roman were not able to unify the Iberian peninsula until the first century A.D. According to legend the hill people of Numantia along the Duero refused to bow to he Romans when the invaded in 133 B.C. and committed mass suicide rather than being taken.

The Romans called the Iberian peninsula Hispania. They gave Spain laws, roads, temples, aqueducts and bridges. In return Spain provided Rome with meals, grains, olives, metals and wine. Three of Rome's most influential emperors—Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Auerlius—came from Spain as did the great Roman poet Seneca.

The Romans turned some native cities outside their two provinces into tributary cities and established outposts and Roman colonies to expand their control. Administrative arrangements were ad hoc. Governors who were sent to Hispania tended to act independently from the Senate due to the great distance from Rome. This changed after the end of the Republic and the establishment of rule by emperors in Rome. After the Roman victory in the Cantabrian Wars in the north of the peninsula (the last rebellion against the Romans in Hispania), Augustus conquered the north of Hispania, annexed the whole peninsula and carried out administrative reorganisation in 19 B.C. [Source Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: SPAIN IN THE ANCIENT ROMAN ERA europe.factsanddetails.com

Austria and Switzerland in the Roman Era

chained Germanic

Noricum is the Latin name for a federation of tribes that included most of what is now Austria and part of Slovenia. In the A.D. first century, it became a province of the Roman Empire. Its borders were the Danube to the north, Raetia and Vindelici to the west, Pannonia to the east and south-east, and Italia to the south. The kingdom was founded around 400 BC, and had its capital at the royal residence at Virunum on the Magdalensberg. [Source Wikipedia]

In the A.D. first century, the Romans conquered the Celts south of the Danube and set up a frontier colony. Although Noricum and Rome had been active trading partners and had formed military alliances, around 15 B.C. the majority of modern Austria was annexed to the Roman Empire, ushering in 500 years of Roman rule there. Noricum became a Roman province. The Romans built many cities that survive today. They include Vindobona (Vienna), Juvavum (Salzburg), Valdidena (Innsbruck), and Brigantium (Bregenz). As Rome's power declined, Germanic tribes from the north moved in and overcame the Celts.

What is now Switzerland was a part of the Roman Republic and Empire for a period of about 600 years six centuries, beginning with the step-by-step conquest of the area by Roman armies from the 2nd century B.C. and ending with the Fall of the Western Roman Empire in the A.D. 5th century. The mostly Celtic tribes of the area were subdued jugated by successive Roman campaigns aimed at control of the strategic routes from Italy across the Alps to the Rhine and into Gaul, most importantly by Julius Caesar's defeat of the largest tribal group, the Helvetii, in the Gallic Wars in 58 B.C.

European Provinces in Central Europe

Rhaetia et Vindelicia (roughly Switzerland, northern Italy,15 B.C.). Noricum (Austria, Slovenia, 15 B.C.).

Pannonia (western Hungary, eastern Austria, northern Croatia, north-western Serbia,

northern Slovenia, western Slovakia and northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. A.D. 10).

See Separate Article: CENTRAL EUROPE AND THE ALPS DURING THE ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com

Balkans in the Roman Era

The Balkans, which corresponds partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with a number geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the whole of Bulgaria and into other countries. The Balkan Peninsula is bordered by the Adriatic Sea in the northwest, the Ionian Sea in the southwest, the Aegean Sea in the south, the Turkish straits in the east, and the Black Sea in the northeast. The Balkan countries are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, and Slovenia. All or part of each of these countries located within the Balkan peninsula. Parts of Greece and Turkey are also located within the Balkan geographic region. [Source Wikipedia, Encyclopedia Britannica]

In the third century B.C., Rome conquered the west Adriatic coast and began exerting influence on the opposite shore. Greek allegations that the Illyrians were disrupting commerce and plundering coastal towns helped precipitate a Roman punitive strike in 229 B.C., and in subsequent campaigns Rome forced Illyrian rulers to pay tribute. Roman armies often crossed Illyria during the Roman-Macedonian wars, and in 168 B.C. Rome conquered the Illyrians and destroyed the Macedonia of Philip and Alexander. For many years, the Dinaric Alps sheltered resistance forces, but Roman dominance increased. In 35 B.C., the emperor Octavian conquered the coastal region and seized inland Celtic and Illyrian strongholds; in A.D. 9, Tiberius consolidated Roman control of the western Balkan Peninsula; and by A.D. 14, Rome had subjugated the Celts in what is now Serbia. The Romans brought order to the region, and their inventive genius produced lasting monuments. But Rome's most significant legacy to the region was the separation of the empire's Byzantine and Roman spheres (the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, respectively), which created a cultural chasm that would divide East from West, Eastern Orthodox from Roman Catholic, and Serb from Croat and Slovene. [Source: Glenn E. Curtis, Library of Congress, December 1990 *]

Over the next 500 years, Latin culture permeated the region. The Romans divided their western Balkan territories into separate provinces. New roads linked fortresses, mines, and trading towns. The Romans introduced viticulture in Dalmatia, instituted slavery, and dug new mines. Agriculture thrived in the Danube Basin, and t

See Separate Article: BALKANS AND THRACE IN THE ANCIENT ROMAN ERA europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Conquest and Occupation of Britain

Britain was conquered in A.D. 43 by four Roman legions under the crippled Emperor Claudius. In 51 the native leader Cartatcus was captured and taken to Rome. Late an insurrection led by Boudicca, queen of Iceni, was brutally put down.

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “Rome invaded Britain because it suited the careers of two men. The first of these was Julius Caesar. This great republican general had conquered Gaul and was looking for an excuse to avoid returning to Rome. Britain afforded him one, in 55 B.C., when Commius, king of the Atrebates, was ousted by Cunobelin, king of the Catuvellauni, and fled to Gaul. Caesar seized the opportunity to mount an expedition on behalf of Commius. He wanted to gain the glory of a victory beyond the Great Ocean, and believed that Britain was full of silver and booty to be plundered. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

The Romans occupied England for about 400 years. They planted vineyards, chestnut trees and cabbages. Describing the ancient Britons, Julius Caesar reported, "The husbands possess their wives to the number of 10 or 12 in common, and more especially brother with brothers." Caesar also reported that ancient Picts ran round in cold Scotland in the nude.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMAN CONQUEST OF BRITAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN OCCUPATION OF BRITAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

RISE AND FALL OF ROMAN BRITAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BOUDICCAN REBELLION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HADRIAN’S WALL europe.factsanddetails.com ;

VINDOLANDA: ROMAN SOLDIER LIFE AND LETTERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Notitia Dignitatum (Register of Dignitaries), A.D. 400

The Notitia Dignitatum (Register of Dignitaries, c. A.D. 400) is an official listing of all civil and military posts in the Roman Empire, East and West. It survives as a 1551 copy of the now-missing original and is the major source of information on the administrative organization of the late Roman Empire. William Fairley wrote: “The Notitia Dignitatum is an official register of all the offices, other than municipal, which existed in the Roman Empire.... Gibbon gave to this document a date between 395 and 407 when the Vandals disturbed the Roman regime in Gaul. [Source: Notitia Dignitatum (Register of Dignitaries), William Fairley, in Translations and Reprints from Original Sources of European History, Vol. VI:4 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 1899].

“The Notitia Dignitatum has preserved for us, as no other document has done, a complete outline view of the Roman administrative system in early fifth century. The hierarchic arrangement is displayed perfectly. The division of prefectures, dioceses and provinces, and the rank of their respective governors is set forth at length. The military origin of the whole system appears in the titles of the staff officers, even in those departments whose heads had, since the time of Constantine, been deprived of all military command.”

Register of Dignitaries in the West

Register of the Dignitaries Both Civil and Military, in the Districts of the West:

The pretorian prefect of Italy.

The pretorian prefect of the Gauls.

The prefect of the city of Rome.

The master of foot in the presence.

The master of horse in the presence.

The master of horse in the Gauls.

The provost of the sacred bedchamber.

The master of the offices.

The quaestor.

The count of the sacred bounties.

The count of the private domains.

The count of the household horse.

The count of the household foot.

The superintendent of the sacred bedchamber,

The chief of the notaries.

The castellan of the sacred palace.

The masters of bureaus:

of memorials; of correspondence; of requests.

The proconsul of Africa.

[Source: Notitia Dignitatum (Register of Dignitaries), William Fairley, in Translations and Reprints from Original Sources of European History, Vol. VI:4 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 1899].

Roman Empire in AD 460

Six vicars: of the city of Rome; of Italy; of Africa; of the Spains; of the Seven Provinces; of the Britains.

Six military counts: of Italy; of Africa; of Tingitania; of the tractus Argentoratensis; of the Britains; of the Saxon shore of Britain.

Thirteen dukes: of the frontier of Mauritania Caesariensis; of the Tripolitan frontier; of Pannonia prima and ripuarian Noricum; of Pannonia secunda; of ripuarian Valeria; of Raetia prima and secunda; of Sequanica; of the Armorican and Nervican tract; of Belgica secunda; of Germania prima; of Britannia; of Mogontiacensis.

Twenty-two consulars: of Pannonia;

in Italy eight: of Venetia and Histria; of Emilia; of Liguria; of Flaminia and Picenum annonarium; of Tuscia and Umbria; of Picenum suburbicarium; of Campania;of Sicilia.

in Africa two: of Byzacium; of Numidia.

in the Spains three: of Beatica; of Lusitania; of Callaecia.

in the Gauls six: of Viennensis; of Lugdunensis prima; of Germania prima; of Germania secunda; of Belgica prima; of Belgica secunda.

in the Britains two: of Maxima Caesariensis, of Valentia.

Three correctors:

in Italy two: of Apulia and Calabria; of Lucania and Brittii.

in Pannonia one: of Savia.

Thirty-one presidents:

in Illyricum four: of Dalmatia; of Pannonia prima; of Mediterranean Noricum; of ripuarian Noricum,

in Italy seven: of the Cottiau Alps; of Reetia prima; of Raetia secundum, of Samnium; of Valeria; of Sardinia; of Corsica.

in Africa two of Mauritania Sitifensis; of Tripolitana.

in the Spains four: of Tarraconensis; of Carthaginensis; of Tintgjtania; or the Balearic Isles.

in the Gauls eleven: of the maritime Alps; of the Pennine and Graian Alps of Maxima Sequanortim; of Aquitanica prima; Aquitanica secunda; of Novempopulana; of Narbonensis prima; of Narbonensis secunda; of Lugdunensis secunda; of Lugduneasis tertia; of Lugunensis Senonica.

in the Britains three: of Britannia prima; of Ezitannia secunda; of Flavia Caesariensis.

Count of the Sacred Bounties

Under the control of the illustrious cou n t of the sacred bounties.

The count of the bounties in Illyricum,

The count of the wardrobe,

The count of gold,

The count of the Italian bounties,

Accountants:

The accountant of the general tax of Pannonia secunda, Dalmatia and Savia,

The accountant of the general tax of Pannonia prima, Valeria, Mediterranean and ripuarian Noricum.

The accountant of the general tax of Italy,

The accountant of the general tax of the city of Rome,

The accountant of the general tax of the Three Provinces, that is, of Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica,

The accountant of the general tax of Africa,

The accountant of the general tax of Numidia,

The accountant of the general tax of Spain,

The accountant of the general tax of the Five Provinces,

The accountant of the general tax of the Gauls,

The accountant of the general tax of the Britains.

[Source: Notitia Dignitatum (Register of Dignitaries), William Fairley, in Translations and Reprints from Original Sources of European History, Vol. VI:4 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 1899].

Provosts of the storehouses:

In Illyricum:

The provost of the storehouses at Salona in Dalmatia,

The provost of the storehouses at Siscia in Savia

The provost of the storehouses at Savaria in Pannonia prima,

In Italy:

The provost of the storehouses at Aquileia in Venetia,

The provost of the storehouses at Milan in Liguria,

The provost of the storehouses of the city of Rome,

The provost of the storehouses at Augsburg in Raetia secunda.

In the Gauls:

The provost of the storehouses at Lyons,

The provost of the storehouses at Arles,

The provost of the storehouses at Rheims,

The provost of the storehouses at Trier.

In the Britains:

The provost of the storehouses at London.

Procurators of the mints:

The procurator of the mint at Siscia,

The procurator of the mint at Aquileia,

The procurator of the mint in the city of Rome,

The procurator of the mint at Lyons,

The procurator of the mint at Arles,

The procurator of the mint at Trier.

Procurators of the weaving-houses:

The procurator of the weaving-house at Bassiana, in Pannonia secunda -removed from Salona,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Sirmium. in Pannonia secunda,

The procurator of the Jovian weaving-house at Spalato in Dalmatia,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Aquileia in Venetia inferior,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Milan in Liguria,

The procurator of the weaving-house in the city of Rome,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Canosa and Venosa in Apulia,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Carthage in Africa,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Arles in the province of Vienne,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Lyons,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Rheims in Belgica secunda,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Tourney Belgica Secunda,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Trier in Belgica secunda,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Autun- removed from Metz,

The procurator of the weaving-house at Winchester Britain.

Procurators of the linen-weaving houses:

The procurator of the linen-weaving house at Vienne in the Gauls,

The procurator of the linen-weaving house at Ravenna in Italy.

Procurators of the dye-houses:

The procurator of the dye-house at Tarentum in Calabria,

The procurator of the dye-house at Salona in Dalmatia

The procurator of the dye-house at Cissa in Venetia and Istria,

The procurator of the dye-house at Syracuse in Sicily,

The procurator of the dye-houses in Africa,

The procurator of the dyeihouse at Girba, in the Province of Tripolis,

The procurator of the dye-house in the Balearic Isles in Spain,

The procurator of the dye-house at Toulon in the Gauls.

The procurator of the dye-house at Narbonne.

Procurators of the embroiderers in gold and silver:

The procurator of the embroiderers in gold and silver at Arles,

The procurator of the embroiderers in gold silver and at Rheims,

The procurator of the embroiderers in gold and silver at Trier,

Procurators of the goods despatch:

For the Eastern traffic:

The provost of the first Eastern despatch, and the fourth [return],

The provost of the second Eastern despatch, and the third [return],

The provost of the second [return] despatch, and the third from the East,

The provost of the first (return] despatch, and the fourth from the East.

For the traffic with the Gauls:

The provost of the first Gallic despatch, and the fourth [return].

The counts of the markets in Illyricum.

The staff of the aforesaid illustrious count of the sacred bounties includes:

A chief clerk of the whole staff,

A chief clerk of the bureau of fixed taxes,

A chief clerk of the bureau of records,

A chief clerk of the bureau of accounts,

A chief clerk of the bureau of gold bullion,

A chief clerk of the bureau of gold for shipment,

A chief clerk of the bureau of the sacred wardrobe,

A chief clerk of the bureau of silver,

A chief clerk of the bureau of miliarensia,

A chief clerk of the bureau of coinage, and other clerks,

A deputy chief clerk of the staff, who is chief clerk of the secretaries,

A sub-deputy chief clerk who has charge of the goods despatch.

Administrative Positions in Europe

Vicar of the Seven Provinces

Under the control of the worshipful vicar of the Seven Provinces:

Consulars:

of Vienne,

of Lyons,

of Germania prima,

of Germania secunda,

of Belgica, prima,

of Belgica secunda.

Presidents:

of the Maritime Alps,

of the Pennine and Graiam Alps,

of Maxima Sequanorum,

of Aquitanica prima,

of Aquitanica secunda,

of Novem populi,

of Narbonensis prima,

of Narbonensis secunda,

of Lugdunensis secunda,

of Lugdunensis tertia,

of Lugdunensis Senonia.

The staff of the aforesaid worshipful vicar of the Seven. Provinces:

[The same as in No. XIX.]

[Source: Notitia Dignitatum (Register of Dignitaries), William Fairley, in Translations and Reprints from Original Sources of European History, Vol. VI:4 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 1899].

Vicar of the Britains

Under the control of the worshipful vicar of the Britains:

Consulars:

of Maxima Caesariensis,

of Valentia.

Presidents:

of Britannia prima,

of Britannia secunda,

of Flavia Caesariensis.

The staff of the same worshipful vicar is as follows:

[The same as in No. XIX]

Count of Tingitania

Under the control of the worshipful count of Tingitania:

Borderers:

[One prefect of a squadron, and seven tribunes of cohorts.]

The staff of the same worshipful count is as follows:

A chief of staff from the staffs of the masters of the soldiery in the presence; one year from that of the master of the foot, the other from that of the master of horse.

A custodian as above,

Two accountants, in alternate years from the aforesaid staffs.

A chief deputy,

A chief assistant,

An assistant,

A registrar,

Secretaries,

Notaries and other officials.

Duke of the Armorican Tract

Under the control of the worshipful duke of the Armorican and Nervican tract:

[One tribune of a cohort and nine military prefects.] *enumeration omitted

The Armorican and Nervican tract is extended to include the Five Provinces:

Aquitanica prima and secunda, Lugdunensis secunda and tertia.

The staff of the same worshipful duke includes:

A chief of staff from the staffs of the masters of soldiery in the presence in alternate years,

An accountant from the staff of the master of foot for one year,

A custodian from the aforesaid staffs in alternate years

A chief assistant;

An assistant,

A registrar,

Secretaries,

Notaries and other officials.

Consular of Campania

Under the control of the right honorable consular of Campania:

The province of Campania.

His staff is as follows:

A chief of staff from the staff of the pretorian prefect of Italy,

A chief deputy,

Two accountants,

A chief assistant,

A custodian,

A keeper of the records,

An assistant,

Secretaries and other cohartalini, who are not allowed to pass to another service without the permission of the imperial clemency.

All the other consulars have a staff like that of the consular of Campania.

Corrector of Apulia and Calabria.

Under the jurisdiction of the right honorable corrector of Apulia and Calabria:

The province of Apulia and Calabria.

His staff is as follows:

A chief of the same staff,

A chief deputy,

Two accouutants,

A custodian,

A chief assistant,

A keeper of the records,

An assistant,

Secretaries and other cohortalini, who are not allowed to pass to another service without the permission of the imperial clemency.

The other correctors have a staff like that of the corrector of Apulia and Calabria.

President of Dalmatia.

Under the jurisdiction of the honorable president of Dalmatia.

The province of Dalmatia.

His staff is as follows.

[The same as in others]

The other presidents have a staff like that of the president Dalmatia

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024