Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

EVERYDAY LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME

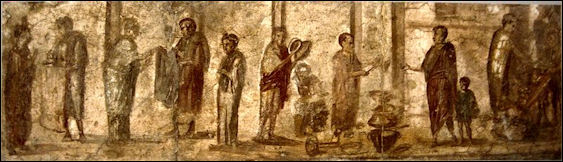

Pompeii fresco

In much of the ancient Roman Empire people tended to wake up at dawn and go to the fields and do whatever work or chores they had to do first thing in the morning. The forum was the main square or market place of a Roman city. It was the center of Roman social life and the place where business affairs and judicial proceedings were carried out. Here, orators stood on podiums pontificating about the issues of the days, priests offered sacrifices before the gods, chariot-borne emperors rode past worshipping crowds, and people milled about shopping, gossiping and simply hanging out.

It is believed that rural people in Roman era tended to wake up at dawn and go to the fields and do whatever work or chores they had to do first thing in the morning. Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The way in which a Roman spent his day depended, of course, upon his position and business, and varied greatly with individuals and with the particular day. The ordinary routine of a man of the higher class, the man of whom we read most frequently in Roman literature, was something like this. He rose at a very early hour—he began his day before sunrise, because it ended so early. After a simple breakfast he devoted such time at home as was necessary to his private business, looking over accounts, consulting with his managers, giving directions, etc. Cicero and Pliny the Elder found these early hours the best for their literary work. Horace tells of lawyers giving free advice at three in the morning. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“After his private business was dispatched, the man took his place in the atrium for the salutatio, when his clients came to pay their respects, perhaps to ask for the help or advice that he was bound to furnish them. All this business of the early morning might have to be dispensed with, however, if the man was asked to a wedding, or to be present at the naming of a child, or to witness the coming of age of the son of a friend, for all these semi-public functions took place in the early morning. But after them or after the levee the man went to the Forum, attended by his clients and carried in his litter with his nomenclator at his elbow. The business of the courts and of the senate began about the third hour, and might continue until the ninth or tenth; that of the senate was bound to stop at sunset. Except on extraordinary occasions all business was pretty sure to be over before eleven o’clock, and at this time the lunch was taken. |+|

“Then came the midday siesta (meridiatio), so general that the streets were as deserted as at midnight; one of the Roman writers fixes upon this as the proper time for a ghost story. Of course there were no sessions of the courts or meetings of the senate on the public holidays; on such days the hours generally given to business might be spent at the theater or the circus or other games. As a matter of fact some Romans of the better class rather avoided these shows, unless they were officially connected with them, and many of them devoted the holidays to visiting their country estates.

Pompeii tools

"After the siesta, which lasted for an hour or more, the Roman was ready for his regular athletic exercise and bath, either in the Campus, and the Tiber or in one of the public bathing establishments. The bath proper was followed by the lounge, or perhaps by a promenade in the court, which gave a chance for a chat with a friend, or an opportunity to hear the latest news, to consult business associates, in short to talk over any of the things that men now discuss at their clubs. After this came the great event of the day, the dinner, at one’s own house or at that of a friend, followed immediately by retirement for the night. Even on the days spent in the country this program would not be materially changed, and the Roman took with him into the provinces, so far as possible, the customs of his home life. |+|

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT ROMAN POSSESSIONS, TOOLS AND PERSONAL OBJECTS europe.factsanddetails.com ; LIFESTYLE OF THE UPPER CLASSES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins (1986) Amazon.com;

“Life in Ancient Rome: People & Places”, 450 Pictures, Maps And Artworks,

by Nigel Rodgers (2014) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“A Week in the Life of a Roman Centurion” by Gary M. Burge (2015) Amazon.com;

“Populus: Living and Dying in Ancient Rome” by Guy de la Bédoyère (2024) Amazon.com;

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Paul Roberts Amazon.com;

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Communications and Mail in the Roman Empire

There was no postal service or mail delivery in ancient times. A person who wrote a letter had to track someone down who was heading to the same destination as the letter and that someone had to be persuaded and given incentive or money to deliver it.

One letter received in the A.D. 2nd century read: "I was delighted to get your letter, which was given to me by the sword maker; the one you say you sent with Platon's son, I haven't got." Another read; "I sent you two other letters, one by Nedymos and one by Kronios, the armed guard. I've received the one you sent with an Arab."

One daughter in Egypt wrote her mother: "I found no way I could get to you, since the camel-drivers didn't want to go to Oxyrhynchus. Not only that, I also went up to Antinoe to take a boat, but didn't find any. So now I've thought it best to forward the baggage to Antonoe and wait there til I can find a boat and sail. Please give the bearers of this letter 2 talents and 300 drachmas...to pay for transportation...If you you don't have it at hand borrow it...and pay them, since they can't wait around even an hour."

There were no addresses and only the main streets had names. People dropping off letters had to be given careful instructions on where to deliver it. One set of instruction read, "From Moon gate walks as if toward the granaries...and at the first street in back of the baths turn left...Then go west. Then go to the steps and up the other steps and turn right. After the temple precinct there is a seven story house with a basket-weaving establishment. Inquire there from the concierge...Then give a shout."

The only postal system was for government couriers, who were often slaves. The words diplomacy and diploma come from the Greek word “diploma”, which means "doubled" or "folded." This was a reference to how special messages were folded and sealed to be kept secret. The Romans placed important documents on a bronze diptych and were folded shut and sealed. Bronze seals with names of homeowners and administrators have been found.

scenes from the Forum market

Roman Forum

The Roman Forum (between the Colosseum, Palatine Hill and Capitoline Hill) is a huge jumble of weathered arches, fallen columns, broken pedestals, stone blocks and buildings still in the process of being restored. Set up like a big park, it is a good place to stroll around admire Roman architecture and watch cats fight.

Situated in a long green valley that was originally a swamp, it was used by the predecessors of the Etruscans to bury their dead. The Etruscans and Greeks set up a market there. The early Romans established a village where Romulus held a meeting on 753 B.C. that led to the rape of the Sabine women. In Imperial Rome, , the Forum was sort of like New York's Park Avenue and Washington D.C.'s Mall all rolled into one. It was the political and economic center of Rome and the main gathering place for Rome's people.

People came here to chat and gossip with their friends; to listen to orators and politicians, who stood on podiums pontificating about the issues of the day; to worship and make sacrifices to their pagan Gods; and to shop for foodstuffs and items brought in from as far as Africa and Persia. Emperors and noblemen built their palaces on the hills surrounding the Forum.

For 500 years, until the middle of the 5th century when Rome was sacked, every emperor raised new monuments in the Forum. After Rome was claimed by Barbarian tribes, the Forum was abandoned and ignored. When archeologists began excavating it in the 19th century it was covered by 20 feet of soil and cattle grazed on the grass above it.

The Forum today is divided into the Civic Forum (Capitoline Hill side of the Forum), Market Quare, the Lower Forum, the Upper Forum (Colosseum-side entrance of the Forum), the Velia and Palantine Hill. As is true with the Colosseum, most of the buildings are the brick superstructures of the originals, whose marble facades were dismantled and carted away and used to make other building in Rome such as St. Peter's Basilica. Some of the pieces of stone have numbers on them to identify their position. The Temple of Mars Ultor (mars the Avenger) is dedicated to the god of war for avenging Rome after the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Lighting in Ancient Rome

lamp The habit of rising and going to bed early which prevailed in Greece and Italy is easily understood when we see the meagre arrangements for lighting which they possessed. In the street torches were carried, and they were also used in the house in early times. A bronze torch-holder of the late sixth century from Cyprus in the corridor and a terracotta example appear to have been made so that they could be set on a table. The Romans and Etruscans made candles of pitch and also wax ones very similar to our own, but the Greeks were not acquainted with them until they were introduced by the Romans. The iron candelabrum was designed to hold candles on the prickets around the top. Lamps were commonly of terracotta or bronze. Olive oil was burnt in them with a wick of flax, but at best the light must have been poor and flickering. Candelabra were commonly made of wood, but handsomer ones were of bronze. A fine Etruscan candelabrum stands was probably furnished with hooks or other attachments for hanging lamps, or with prickets for candles. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

The earliest lamps were made from sea shells. These were observed in Mesopotamia. Lamps made from man-made materials such as earthenware and alabaster appeared between 3500 and 2500 B.C. in Sumer, Egypt and the Indus Valley. Metal lamps were rare. As technology advanced a groove for the wick was added, the bottom of the lamp was titled to concentrate the oil and the place where the flame burned was moved away from the handle. Mostly animal fats and vegetable and fish oils were burned. In Sumer, seepage from petroleum deposits was used. The wicks were made from twisted natural fibers.

Houses were lit with oil lamps, and cooking was done with coals placed in a metal brazier. Fires were always a hazard and it was not unusual for entire towns to burn down after someone carelessly knocked over an oil lamp. Greeks and Romans used oil lamps made of bronze, with wicks of oakum or linen. They were fueled by edible animal fats and vegetables oils which could be consumed in times of food shortages. The Romans were perhaps the first people to use oil as a combustible material; they burned petroleum in their lamps instead of olive oil.

In ancient times, olive oil was used in everything from oil lamps, to religious anointments, to cooking and preparing condiments and medicines. It was in great demand and traveled well and people like the Philistines grew rich trading it.

Morning in Ancient Rome

To begin with, Imperial Rome woke up as early as any country village at dawn, if not before. Let us revert to an epigram of Martial's, where the poet enumerates the causes of insomnia which in his day murdered sleep for the luckless city dweller. Before the sun was up, he was a martyr to the deafening din of streets and squares where the metalworker's hammer blended with the bawling of the children at school: "The laughter of the passing throng wakes me and Rome is at my bed's head.... Schoolmasters in the morning do not let you live; before daybreak, bakers; the hammers of the coppersmiths all day." To protect themselves against the clatter, the wealthy retired to the depths of their houses, isolated by the thickness of their walls and the garden shrubberies which shut them in. But even there they were assailed from within by the teams of slaves whose duty it was to clean the house. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Food crockery display Day had scarcely broken when a crowd of servants, their eyes still swollen with sleep, were turned loose by the sound of a bell and flung themselves on the rooms, armed with an arsenal of buckets, of cloths (ntappae), of ladders (scalae) to reach the ceilings, of poles (perticae) with sponges (spongiae) attached to the end, feather dusters, and brooms (scopae). The brooms were made of green palms or twigs of tamarisk, heather, and myrtle twisted together. The cleaners scattered sawdust over the floors; then they swept it off again with the accumulated dirt; they dashed with their sponges to attack the pillars and cornices; they cleaned, they scrubbed, they dusted with noisy fervour. If the master of the house was expecting an important guest, he would often rise himself to bring them into action and his imperious or fretful voice would pierce their hullabaloo, as, whip in hand, he shouted : "Sweep the pavement! Polish up the pillars! Down with that dusty spider, web and all! One of you clean the flat silver, another the embossed vessels!" Even if the master depended on a steward to carry out this supervision, he was none the less awakened by the racket of his servants, unless, like Pliny the Younger in his Laurentine villa, he had taken the precaution to interpose the silence of a corridor between his bedchamber and the commotion of the morning.

In general, however, the Romans.were early risers. In the ancient town the artificial light was so deplorable that the rich were as eager as the ppor to profit by the light of day. Each man took the maxim of the elder Pliny as his motto "To live is to be awake: profecto enim vita vigilia est." Ordinarily no one lay in bed of a morning save the young roisterers or the drunkards who were forced to sleep off their overnight excesses. Even some of these were up and about by noon, for "the fifth hour" at which, according to Persius, they made up their minds to go out, normally finished about n A.M. The "late morning" when Horace betook himself in state to the Forum, and which was a luxury Martial could allow himself only in his distant Bilbilis, meant the third or fourth hour, which in summer ended at about 8 or 9 A.M.

Morning Routine in Ancient Rome

The habit of getting up at dawn was so deeply ingrained that even if a person lay abed late he still woke before daybreak and took up the thread of his normal occupations in his bed by the flickering and indifferent light of the wick of tow and wax. From this light (lucubrum) came the words "lucubratio" and "lucubrare" which have given us the English "lucubration." From Cicero to Horace, from the two Plinys to Marcus Aurelius, distinguished Romans vied with each other in "lucubrating" every winter; and the year round the Naturalist, having closed his night with fiis lucubrations, would wait upon Vespasian before daybreak, when the emperor likewise chose to transact business, in order to submit reports and open his master's correspondence. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

There was practically no interval between leaping out of bed and leaving the house. Getting up was a simple, speedy, instantaneous process. Only one single villa, that of Diomedes, has been excavated in Pompeii where the master's bedroom included a zotheca or alcove equipped with a table and a basin. In the text of Suetonius where we are allowed to witness the rising of Vespasian, the subject of a morning wash is passed over in silence; and though the same Suetonius mentions it in telling of the last hours of Domitian, his allusion is too elliptic for us to attach much importance to it. Terrified by the prophecy that the fifth hour of September 18, 96 A.D. the hour at which in fact he died a bloody death was to be inexorably fatal to him, the emperor had mewed himself in his room and had not quitted his bed the whole morning. He remained seated on the bolster beneath which he had a sword concealed. Then suddenly, at the false news that the sixth hour had come, when actually the fifth had but begun, he decided to get up and proceed to the care of his body ( A.D. corporis curam) in an adjacent room.

But Parthenius, his chamberlain, who was one of the conspirators, kept him back on the pretext that a visitor was insisting on making grave revelations to him in person. Suetonius unfortunately has not specified what were the cares which he was going to give his body when the assassins' plot prevented him. The brevity of the allusion, the readiness with which Domitian was turned aside from his intention, indicate that nothing very serious was intended. The word sapo in those days was used only for a dye, and the use of soap in our sense was still unknown, so that at most he may have meant to tfip his face and hands in fresh water. This was the limit of the cura corporis of the fourth century which Ausonius versified in a charming little ode of his Ephemeris, the Occupations of a Day: "Come, slave, up! Give me my slippers and my 7muslin mantle. Bring me the amictus you have got ready for me, for I am going forth. And pour out the running water that I may wash my hands, my mouth, my eyes.

Afternoon Activities in Ancient Rome

After the prandium (lunch) came the midday rest or siesta (meridiatio). |+|when all work was laid aside until the eighth hour, except in the law courts and in the senate. In the summer, at least, everybody went to sleep, and even in the capital the streets were almost as deserted as at midnight. The vesperna, entirely unknown in city life, closed the day on the farm. It was an early supper which consisted largely of the leavings of the noonday dinner with the addition of such uncooked food as a farm would naturally supply. The word merenda seems to have been applied in early times to this evening meal, and then to refreshments taken at any time. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Many Romans spent at least part of their afternoon at the baths. People did not bath in their homes in the evening or morning. Most houses didn't have baths. Most people bathed in the afternoon in public baths. By the time of Jesus, almost every village and town had at least one public bath. Some of them were donated by rich citizens; other charged admission, with the admission price being low enough in most cases that everyone was welcome. A census during the first century A.D. counted more than 1000 such facilities in Rome (a fivefold increase from a 100 years before). Baths were so popular that government passed laws regulating opening and closing times. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

The Romans loved their bathes and much of Roman social life centered around them. Bathing was both a social duty and a way to relax. During the early days of Roman baths there were no rules about nudity or the mixing of the sexes, or for that matter rules about what people did when they were nude and mixing. For women who had problems with this arrangement there were special baths for women only. But eventually the outcry against promiscuous behavior in the baths forced Emperor Hadrian to separate the sexes.

After the fatigue of the sports and tonic of the bath came dinner. The sun is sloping toward its setting and still we have not seen the Romans eat. In reading the lives of Vitellius and his like, it would be easy to imagine that the Romans passed their whole life at table. When we look more closely at the facts, however, we see that for the most part they did not sit down to table till their day was done.

Getting a Picture of Everyday Life by Studying Pompeii’s Garbage

Researchers at Pompeii have done a systematic survey of street trash, buckets and even storage containers to gain an understanding of the relationship between Romans and their possessions. “We’re actually starting to see evidence of people’s choices and how they dealt with their objects,” Caroline Cheung, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, involved in the project, told USA Today. “We get a sense of how people were using them, how they were storing them, whether they were throwing them away or keeping them.” [Source: Traci Watson, USA Today, January 20, 2017 ]

Traci Watson of USA Today wrote: “The humble objects left behind show that people didn’t necessarily go easy on their possessions, even though the articles of everyday life were often purchased rather than homemade. “Take the objects discovered at a farmhouse near Pompeii, where the cooking range was so heaped with ashes that it’s clear “they just basically didn’t take out the garbage,” says Theodore Peña of the University of California, Berkeley. “Like frat boys.” Peña leads the project, which is taking a close look at artifacts found during previous excavations.

“In a storeroom of the kitchen, shelves held gear that “had the hell beaten out of it,” Peña says. There was a bronze bucket full of dents, perhaps where it had banged into the side of the well just outside the farmhouse. There were pots with bits of the rims broken off and a casserole so badly cracked that it was close to falling apart, but people had kept them to use again. At a complex near Pompeii that seems to have been a wine-bottling facility, there were more than 1,000 amphorae, ceramic vessels that were the shipping containers of their day. Many were patched and waiting to be refilled, presumably with wine, Peña says.

“When the researchers delved into street rubbish, they expected to find lots of broken glass, used for perfume bottles and other common items. Instead they found almost none, a sign that even shards of glass were being collected and made into something else. “It’s too early to say whether the people of Pompeii were thrifty adherents of recycling. But the indications so far are that “ceramics and other types of objects were being reused, repurposed or at least repaired,” Cheung says, in contrast to today’s “throwaway society. … If I break a cheap mug, I probably throw it away. I don’t even think about repairing it.”“

Water Supplies and Sewers in Ancient Rome

aqueduct pipe

Some houses had water piped in but most homeowners had to have their water fetched and carried, one of the main duties of household slaves. Residents generally had to go out to public latrines to use the toilet. According to Listverse: The Romans “had two main supplies of water – high quality water for drinking and lower quality water for bathing. In 600 BC, the King of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus, decided to have a sewer system built under the city. It was created mainly by semi-forced laborers. The system, which outflowed into the Tiber river, was so effective that it remains in use today (though it is now connected to the modern sewerage system). It continues to be the main sewer for the famous amphitheater. It was so successful in fact, that it was imitated throughout the Roman Empire.” [Source: Listverse, October 16, 2009 ]

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “All the important towns of Italy and many cities throughout the Roman world had abundant supplies of water brought by aqueducts from hills, sometimes at a considerable distance. The aqueducts of the Romans were among their most stupendous and most successful works of engineering. The first great aqueduct (aqua) at Rome was built in 312 B.C. by the famous censor Appius Claudius. Three more were built during the Republic and at least seven under the Empire, so that ancient Rome was at last supplied by eleven or more aqueducts. Modern Rome is well supplied by four, which are the sources and occasionally the channels of as many of the ancient ones. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Mains were laid down the middle of the streets, and from these the water was piped into the houses. There was often a tank in the upper part of the house from which the water was distributed as needed. It was not usually carried into many of the rooms, but there was always a fountain in the peristylium and its garden, and a jet in the bathhouse and in the closet. The bathhouse had a separate heating apparatus of its own, which kept the room or rooms at the desired temperature and furnished hot water as required. The poor must have carried the water for household use from the public fountains in the streets. |+|

“The necessity for drains and sewers was recognized in very early times, the oldest at Rome dating traditionally from the time of the kings. Some of the ancient drains, among them the famous Cloaca Maxima, were in use until recent years. |+|

Toilets in Ancient Rome

Toilet in Ephesus Turkey The Romans had flushing toilets. It is well known Romans used underground flowing water to wash away waste but they also had indoor plumbing and fairly advanced toilets. The homes of some rich people had plumbing that brought in hot and cold water and toilets that flushed away waste. Most people however used chamber pots and bedpans or the local neighborhood latrine. [Source: Andrew Handley, Listverse, February 8, 2013 ]

The ancient Romans had pipe heat and employed sanitary technology. Stone receptacles were used for toilets. Romans had heated toilets in their public baths. The ancient Romans and Egyptians had indoor lavatories. There are still the remains of the flushing lavatories that the Roman soldiers used at Housesteads on Hadrian's Wall in Britain. Toilets in Pompeii were called Vespasians after the Roman emperor who charged a toilet tax. During Roman times sewers were developed but few people had access to them. The majority of the people urinated and defecated in clay pots.

Ancient Greek and Roman chamber pots were taken to disposal areas which, according to Greek scholar Ian Jenkins, "was often no further than an open window." Roman public baths had a pubic sanitation system with water piped in and piped out. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

See Separate Article: TOILETS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024