Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

ROMAN HOLIDAYS

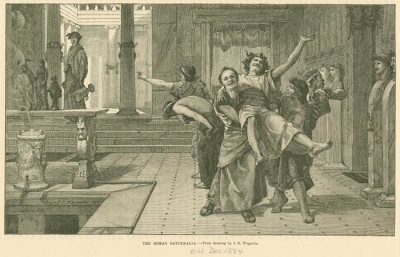

December 25 was not selected as the day for Christmas because it was the date of Jesus' birth but rather because that was the time of the riotous Roman winter festival of Saturnalia, which early Christians aimed to get rid of by having it replaced by Christmas. In ancient Rome, people celebrated Saturnalia for the entire week leading up to the solstice. Historical sources indicate that it was the most wild and popular festive period in the year.

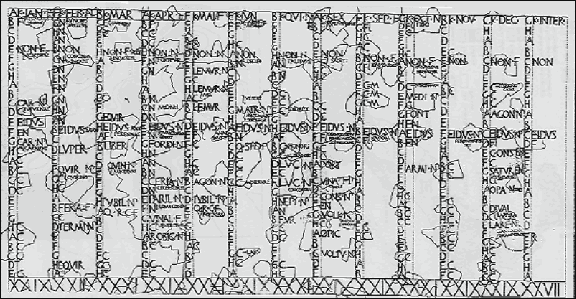

According to Roman tradition legendary King Numa established the Roman calendar with its cycle of feasts and its listing of days on which public business could or could not be conducted (dies fasti et nefasti). The king was the chief priest. He was assisted primarily by two collegiate priesthoods, the College of Pontiffs, and the College of Augurs. After the establishment of the Republic (c. 509 B.C.), the two colleges mentioned became the two most important religious bodies in the state. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The aim of public worship was to assure or to restore the "benevolence and grace of the gods," which the Romans considered indispensable for the state's well-being. Annually returning rituals dominated public cultic activity. The feasts were fixed or movable or organized around some particular circumstance. According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The feriae, a special class of days given to the gods as property (and hence free from every mundane activity) were marked as a special class of dies nefasti (days not to be used), namely as a group of days whose violation made sacrifices performed to ask the gods for forgiveness of transgressions necessary. Many of these festivals go back to the early Republic or an even earlier period. Usually, they were coordinated with the days that structured each month. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

This ritual sequence was punctuated by the rhythm of seasons for the agrarian celebrations (especially in April and in July and August) and by the schedule of training for military campaigns. Apart from the feriae and connected ritual sequences, many commemoration days of the dedication of temples filled the calendar. The annual sacrifice in front of the temple sometimes gave rise to very popular festivals. The Roman liturgy developed in line with an order of feasts consecrated to particular deities. An overlap was therefore possible: since the ides, "days of full light," were always dedicated to Jupiter. The sacrifice of the Equus October (horse of October) on October 15 coincided with the ides.

April Fool's day is thought to date back to the Roman Empire and may have evolved from a festival honoring the goddess Ceres who foolishly chased echos of her daughter Proserpina while Pluto carried her off from the Elysian meadows. Lemuria was a holiday in which people scattered beans, displayed their treasured possessions on a special cabinet and ate fish sausage.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic: An Introduction to the Calendar and Religious Events of the Roman Year” by W Warde Fowler (1899) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Holidays” by Mab Borden (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Festivals in the Greek East: From the Early Empire to the Middle Byzantine Era” by Fritz Graf (2015) Amazon.com;

“A Week in the Life of Rome” by James L. Papandrea (2019) Amazon.com;

“Time in Antiquity” by Robert Hannah Amazon.com;

“Roman Origins of Our Calendar” by Van L. Johnson (1974) Amazon.com;

“On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity” by Michele Renee Salzman (1991) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Calendars: Constructions of Time in the Classical World” by Robert Hannah (2005) Amazon.com;

“Cæsar's Calendar: Ancient Time and the Beginnings of History” by Denis Feeney (2008) Amazon.com;

“Calendarium Perpetuum: A Modern Edition of the Ancient Roman Calendar”

by L. Vitellius Triarius (2013) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (Reissue Edition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

“The Calendar: The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Calendars and Constellations” by Emmeline M. Plunket (1903) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Early Festivals in Ancient Rome

The earliest-known festivals in Ancient Rome celebrated the city’s legendary founding and growth. According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The Lupercalia, celebrated on February 15, delimited the very cradle of the city. On that date "the old Palatine stronghold ringed by a human flock" (Varro, De lingua Latina) was purified by naked Luperci (a variety of wolf-men, dressed in loincloths), who, armed with whips, would flog the public. Everything about this ceremony — the "savage" rite (see Cicero, Pro Caelio 26) and the territorial circumscription — demonstrates its extreme archaism.[Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005),Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The feast of Septimontium on December 11 designated a more extended territory. It involved no one except the inhabitants of the montes (mountains). These seven mountains (which are not to be confused with the seven hills of the future Rome) are the following: the knolls of the Palatium, the Germalus, the Velia (which together would make up the Palatine), the Fagutal, the Oppius, the Cespius (which three would be absorbed by the Esquiline), and the Caelius (Sextus Pompeius Festus, while still asserting the number of seven montes, adds the Subura to this list). This amounted, then, to an intermediary stage between the primitive nucleus and the organized city.

The feast of the Argei, which required two separate rituals at two different times (on March 16 and 17, and on May 14), marks the last stage. It involved a procession in March in which mannequins made of rushes (Ovid, Fasti 5.621) were carried to the twenty-seven chapels prepared for this purpose. On May 14 they were taken out of the chapels and cast into the Tiber from the top of a bridge, the Pons Sublicius, in the presence of the pontiff and the Vestal Virgins. There are different opinions on the meaning of the ceremony. Wissowa saw in it a ritual of substitution taking the place of human sacrifices. (A note by Varro, De lingua Latina 7.44, specifies that these mannequins were human in shape.) However, Kurt Latte prefers to compare these mannequins of rushes to oscilla (figurines or small masks that were hung from trees), which absorbed the impurities that were to be purged from the city. The itinerary of the procession shows that it corresponds to the final stage of the city's development, the Rome of the quattuor regiones (four regions). Varro outlined the procession as follows: it proceeded through the heights of the Caelius, the Esquiline, the Viminal, the Quirinal, and the Palatine, and encircled the Forum — henceforth located in the heart of the city.

Types of Holidays in Ancient Rome

The Roman recognized two kinds of days: 1) dies fasti and 2) dies nefasti. On the former, civil and judicial business might be transacted without fear of offending the gods; on the latter such business was suspended. There were also 14 days of a mixed nature when civil affairs might proceed normally after certain rites had been performed or during a certain limited part of the day. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Among the dies nejasti (holidays), we find a certain number characterised as jeriae or public holidays, as well as another group set apart for ludi or public games. Such days are usually marked in surviving calendars with the letters NP and scholars do not agree as to the difference, if any, between the days marked with these two letters and those characterised by the single letter N, meaning nejas? Yet it is certain that jeriae and days set aside for games were public holidays in the present sense of the word, when work was relaxed or suspended altogether, and men gave themselves over to rest and pleasure. It is with these days that we are primarily concerned. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Calendars also record the forty-five feriae publicae, the origins of which are lost in the mists of early Latin history but which were kept up under the empire: among others, the Lupercalia in February; the Parilia, Cerialia, and Vinalia in April; the Vestalia and Matronalia in June; the Volcanalia in August; and the Saturnalia in December. Ceremonies having the nature of games were connected with some of the holidays in this ancient group : for instance, the dance of the Salii which took place on the festival of the Quinquatrus (March 19) and the Armilustrium (October 19), the foot races of the Robigalia (April 25), the races on foot and muleback of the Consualia (August 21 and December 15). But since these festivals were essentially religious and their chief purpose was not the entertainment of the people, we may conveniently set them aside from the days devoted primarily to games. Allowing, then, for overlapping, in that six of these ancient festivals were celebrated on days when games were being held, we have 39 new holidays to add to the previous 93 game days, making a total of 132 days in all.

Finally, in the time of Caesar, we meet a new kind of public holiday, decreed by the Senate to commemorate a significant event in the life of the emperor. The first of these to appear were Caesar's birthday and the anniversaries of five of his most important military victories. The precedent was followed under Augustus and 18 new holidays were proclaimed commemorating secular and religious events of his reign or connected with his memory after death. To these we must add 6 more days pertaining to events extending into the reign of Claudius. But of these 30 new holidays, only 18 do not coincide with days otherwise celebrated, so that our sum total of all holidays reaches an even 150. Finally, 8 of the Ides dedicated to Jupiter and i of the Calends dedicated to Mars do not fall on other holidays and must be added to our list.

There Were Lots of Festivals and Holidays in Ancient Rome

About half of the Roman year was spent in holiday. At the time of Claudius the Roman calendar contained 159 days expressly marked as holidays, of which 93 were devoted to games given at public expense. The list does not include the many ceremonies for which the State took no responsibility and supplied no funds, but which were much in favor among the people and took place around the sanctuaries of the quarters in the chapels of foreign deities whose worship was officially sanctioned, and in the scholae or meeting places of the guilds and colleges. Even less does it take account of the feriae privatae of individuals or family groups. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

After Claudius, we have very little precise information as to public holidays. To be sure, a number of jerialia are still extant lists giving a selected number of days which were celebrated with religious ceremonies by a limited group of people. But in many cases it is difficult to conjecture whether these days were designated as public holidays in the city of Rome. Naturally the list of holidays changed from reign to reign, but the additions seem to have outnumbered the subtractions, for we know that Claudius, 11 Vespasian, 12 and Marcus Aurelius 13 all found it necessary to cut down the number of holidays. Marcus Aurelius, his biographer tells us, restored the business year to 230 days; and from later evidence it has been reasonably conjectured that most of the remaining 135 were devoted to public spectacles. For the manuscript Calendar of Philocalus, written in A.D. 354 and reflecting conditions of the third century, records 175 days of games out of about 200 public holidays, as against 93 out of 159 for the early empire, an increase from about 59 per cent to 87 per cent in the proportion of game days.

We have, moreover, been speaking of ordinary years during which nothing remarkable had happened and the normal program was not combined with the recurrence of quadrennial cycles such as the earlier Actiaca and the later Agon Capitolinus, and at longer intervals with the return of the "renewal of the century" prolonged over a series of days, such as took place in 17 B.C. and in 88 and 204 A.D., or of the "centenaries" of the Eternal City as in 47, 147, and 248. 15 Above all, we must not overlook the festivals which defy exact computation because they were dependent on imperial caprice and might be suddenly inserted in the calendar at any moment. These the Caesars decreed in quantities. They grew in importance with the prosperity of an emperor's reign, and their unexpectedness greatly intensified the interest they aroused. They were the triumphs which an emperor made the Senate decree for him; the munera or gladiatorial combats which he decreed on some arbitrary pretext. These gladiatorial displays soon came to equal the ludi in frequency, and in the second century they sometimes went on for months. 16 The reality, therefore, fir exceeded our statistics; and in attempting to analyse it, we are driven to conclude that in the epoch we are studying Rome enjoyed at least one day of holiday for every working day.

Cycle of Festivals in Ancient Rome

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The calendar of festivals reflected and conventionalized temporal rhythms. The preparation for warfare finds ritual reflection in some festivals and in the ritual activities of the priesthood of the Salii in the month of March, the opening month of the year. Mars is the god presiding over warfare; the Salians performed dances clad in archaic warrior dress and cared for archaically formed shields in the shape of an eight. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Agricultural and pastoral festivals could be found in the month of April, the Parilia with their lustration of cattle being probably the oldest one (April 21). Fordicidia, the killing of pregnant cows (April 15); the Cerialia (April 19), named after the goddess of cereals; the Vinalia, a wine festival (April 23); and the Robigalia, featuring the sacrifice of a dog to further the growing of the grain (April 25), might denote old rituals, too. Series of festivals in August and December, addressed to gods related to the securing of the harvest and abundance, might have produced other foci of communal and urban ritualizing of the economic activities of farmsteads.

The subordination of the festival listed to the monthly — originally empirical, later fictitious — lunar phases of the developed calendar warns of the assumption of complex festival cycles, too easily postulated by scholars like Dumézil. The same warning holds true for the postulation of complex cycles of initiation rites. Sociologically, Rome was not a tribal society, but a precarious public of gentilician leaders and their followers and an increasingly incoherent urban population. What looks like initiatory phenomena are rites reserved mostly for young aristocrats organized as representative priesthoods.

Roman calendar

Important Festivals in Ancient Rome

Two of the most famous Roman holidays were are Saturnalia and Lupercalia (See Below). Ancient Romans exchanged gifts of figs and honey on New Year’s Day and made sure to work part of the day as a good omen for the coming year. Today Italians celebrate December 31 (San Silvestro’s day) with lentils and wearing red underwear is the order to bring good luck in the upcoming year. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 31, 2014]

Forncalia, or “Feast of the Ovens” was a movable feast held in February that centered around baking small cakes from the ground and roasted seeds of the oldest variety of wheats. During the baking an offering was made to the spirit of the oven. After the cakes were cooked the community gathered to eat them.

Terminalia was the main purification holiday of the year. Held in late February and dedicated to Terminus, the god of boundaries and endings, it featured the sacrifice of a lamb and a young pig and a feast with wine and songs. Property owners decorated the boundary stones between properties with garlands and wreaths. A temporary altar was set up and a fire was kindled using a flame brought from the family hearth. Fruit, honey and cakes was thrown into the fire by girls. During a feast everyone wore white. The original purpose of the holiday seems to have been to avoid disputes by standardizing local boundaries.

The month of March contained several feasts marking the opening of martial activities. There was registered on the calendars a sacrifice to the god Mars; the blessing of horses on the Equirria on February 27 and March 14; and the blessing of arms on the Quinquatrus and of trumpets on the Tubilustrium on March 19. In addition, there was the Agonium Martiale on March 17. The Salii, carrying lances (hastae) and shields (ancilia), roamed the city performing martial dances. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Lupercalia

The early Romans practiced a purifying ritual called Lupercalia. Priests sacrificed goats and a dog at the Lupercal, the cave where legend says Romolus and Remus were suckled, and their blood was smeared on two youths. Young women were whipped across their shoulders in the belief it bestowed fertility. The rite was performed in mid February at an altar near Lapis Niger, a sacred site paved with black stones near the Roman Forum until A.D. 494 when it was banned by the pope.

According to persweb: Lupercalia came in the spring and was symbolic of the fertility that spring brought forth. A group of young priests, named the Luperci, ran from Lupercal, a cave at the foot of the Palatine, through the streets, back to the Palatine. They were completely naked, except for a goat skin that was left over from a sacrifice earlier that day. As they made their way through the streets of Rome, the Luperci struck topless women on the breasts with strips of goat skin in order to make them fertile. They also purified the ancient site of Lupercal in this interesting festival. Ovid wrote of the Lupercalia, "Neither potent herbs, nor prayers, nor magic spells shall make of thee a mother, submit with patience to the blows dealt by a fruitful hand."

Saturnalia

“Saturnalia was the winter celebration to the god Saturn. Saturn was identified with the Greek god Kronos, and he was sacrificed to according to Greek ritual during this festival. The Temple of Saturn, the oldest temple recorded by the pontifices, was dedicated on the Saturnalia, and the woolen bonds which fettered the feet of the ivory cult statue within were loosened on that day to symbolize the liberation of the god. [Source: persweb.wabash.edu ~~]

The Saturnalia festival lasted seven days and was celebrated for during week leading up to the winter solstice. Historical sources indicate that it was the most wild and popular festive period in the year. Saturnalia was marked by gift giving. This is one reason why people believe that Saturnalia was absorbed into Christmas. The festival also had a day where the slave and master would trade places. The masters would serve their slaves and the slaves would go out into the streets and gamble with dice, a pastime that was illegal during the rest of the year. On the day of the festival, a sacrifice took place at the Temple of Saturn which was followed by a public banquet. As they left the banquet, the citizens are reputed to have shouted "IO, Saturnalia!"” ~

Candida Moss wrote in The Daily Beast: Just like Christmas today, Saturnalia was part religious festival and part opportunity to skip work and drink too much. According to the agricultural writer Columella, it was officially celebrated on December 17, but by the time of Cicero (first century B.C.) it lasted for three or even seven days. It was a raucous affair with people greeting one another with the traditional “Io, Saturnalia.” Catullus called it “the best of days” complete with food, drink, games, gambling, and gift giving. Homes were decorated with evergreen wreaths and berries and, on the final day (December 23), candles and small terracotta figurines (sigallaria) were given as gifts, particularly to children. The noise of the celebrations got so bad that the Roman statesman and writer Pliny had to construct a special writing chamber to block out the din.[Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast December 25, 2022]

A religious festival that involves candles, gift-giving, evergreen decor, songs, and food, it all sounds a touch familiar but was Saturnalia the source of Christian revelry? There’s no shortage of memes and videos out there but, once again, the timeline is a bit off. Saturnalia finished by December 23 and while we might be tempted to say “well, close enough” the precise date was enormously important because it said something about the importance of Jesus.

Festivals in Ancient Rome

One way Romans showed their respect and reverence of the gods was through festivals. The festivals which were celebrated in honor of the gods were very numerous and were scattered through the different months of the year. The old Roman calendar contained a long list of these festival days. The new year began with March and was consecrated to Mars and celebrated with war festivals. Other religious festivals were devoted to the sowing of the seed, the gathering of the harvest, and similar events which belonged to the life of an agricultural people such as the early Romans were. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Prayers, offerings and sacrifices were key elements of these festivals. The prayers were addressed to the gods for the purpose of obtaining favors, and were often accompanied by vows. The religious offerings consisted either of the fruits of the earth, such as flowers, wine, milk, and honey; or the sacrifices of domestic animals, such as oxen, sheep, and swine. \~\

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Hellas” (c. A.D. 175): “Every year too the people of Patrai celebrate the festival Laphria in honor of their Artemis, and at it they employ a method of sacrifice peculiar to the place. Round the altar in a circle they set up logs of wood still green, each of them sixteen cubits long. On the altar within the circle is placed the driest of their wood. Just before the time of the festival they construct a smooth ascent to the altar, piling earth upon the altar steps. The festival begins with a most splendid procession in honor of Artemis, and the maiden officiating as priestess rides last in the procession upon a car yoked to deer. It is, however, not till the next day that the sacrifice is offered, and the festival is not only a state function but also quite a popular general holiday. For the people throw alive upon the altar edible birds and every kind of victim as well; there are wild boars, deer and gazelles; some bring wolf-cubs or bear-cubs, others the full-grown beasts. They also place upon the altar fruit of cultivated trees. Next they set fire to the wood. At this point I have seen some of the beasts, including a bear, forcing their way outside at the first rush of the flames, some of them actually escaping by their strength. But those who threw them in drag them back again to the pyre. It is not remembered that anybody has ever been wounded by the beasts.” [Source: Pausanias, Pausanias' Description of Greece, translated by A. R. Shilleto, (London: G. Bell, 1900)]

Ludi

rare depiction of Roman men wearing the toga praetexta and participating in what is probably the Compitalia

Michael Van Duisen wrote for Listverse: “The ludi were public games that were normally held in conjunction with religious festivals, though there were occasional events which were secular in nature. Many of them were annual events, especially the religious ones, and the most famous was the Ludi Romani, which honored Jupiter and was held each September. (It’s the oldest of the ludi and was the only one held in Rome for 300 years after it first began.) [Source: Michael Van Duisen, Listverse, February 13, 2014]

“Ludi normally consisted of chariot races, as well as animal hunts. Later editions incorporated gladiatorial combat and there were even special ludi, which were strictly theatrical performances. The ludi with the largest gap in celebration was probably the Ludi Saeculares, or Secular Games. Held in honor of a saeculum, or the longest estimated human lifespan, the Ludi Saeculares were held once every 110 years. (Historian Zosimus actually blames the fall of the Roman Empire on the Romans neglecting to honor this ancient festival.)”

Ludi were days on which performances were held at public expense in the circus or the theater. Based on data down to the time of Claudius, when the evidence of stone calendars breaks off, there were, first of all, the games which the republic at grave crises in its history had decreed in honor of the gods, and which were destined to minister to the ambition of the dictators and the policy of the Caesars: the Ludi Romani, instituted in 366 B.C. and ultimately lasting from September 4 to 19; the Ludi Plebei, which made their appearance somewhere between 220 and 216 B.C. and were then held from November 4 to 17; the Ludi Apollinares, which dated from 208 B.C. and went on from July 6 to 13; the Ludi Ceriales, consecrated to Ceres in 202 B.C., which fitted in between April 12 and 19; the Ludi Mcgalenses, in honor of the Great Idaean Mother of the Gods, Cybele, whose sanctuary was dedicated on the Palatine in 191 B.C., and whose games had since been held every year from April 4 to 10; the Ludi Florales, whose homage the goddess Flora seems regularly to have enjoyed only after 173 B.C., and whose celebration was attended by special ceremonies from April 28 to May 3. All in all, then, we find 59 days devoted to these traditional games of the Roman Republic before the time of Sulla. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The first addition to this group is connected with his name. It is the Ludi Victoria^ Suttanae in the title we can detect Sulla's pretensions to divinity which for two hundred years after his death continued to be held from October 26 to November i. Next, we learn of the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris, which from July 20-30 continued to recall to Roman memory the exploits of the conqueror of Gaul; and the Ludi Fortunae Reducis, which Augustus instituted in n B.C. and which lasted for 10 days from October 3 to 12. To these we must add the 3 days of the Ludi Palatini instituted by Livia in memory of Augustus; 7 the 2 days of the Ludi Martiales celebrated on May 12 and August i in connection with the dedication of the shrine and temple of Mars Ultor; and the day of games celebrating the birthday of the emperor. The sum total for this post-Sullan group is 34 days, which, added to the 59 days of pre-Sullan games, gives us 93 public holidays when the Roman was entertained at spectacles at the expense of the State.

Festival Entertainment in Roman-Era Greece

Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “A festival is celebrated every year at Acharaca; and at that time in particular those who celebrate the festival can see and hear concerning all these things; and at the festival, too, about noon, the boys and young men of the gymnasion, nude and anointed with oil, take out a bull and with haste run before him into the cave; and, when they arrive at the cave, the bull goes forward a short distance, falls, and breathes out his life. [Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, translated by H. C. Hamilton, & W. Falconer, (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857)

The Roman-era Greek orator Dio Chrysostom wrote (A.D. 110): “Some people attend the festival of the god out of curiousity, some for shows and contests, and many bring goods of all sorts for sale, the market folk, that is, some of whom display their crafts and manufactures while others make a show of some special learning — many, of works of tragedy or poetry, many, of prose works. Some draw worshipers from remote regions for religion's sake alone, as does the festival of Artemis at Ephesos, venerated not only in her home-city, but by Hellenes and barbarians.

Clementis Recognitiones wrote (c. A.D. 220): “Most men abandon themselves at festival time and holy days, and arrange for drinking and parties, and give themselves up wholly to pipes and flutes and different kinds of music and in every respect abandon themselves to drunkenness and indulgence.”

Bacchanalian scene

Wild Dionysus Festivals

The Dionysus (Bacchus) Cult was very much alive in the Roman Empire as it was in ancient Greece. To pay their respect to Dionysus, according to ancient sources, the citizens of Athens and other places, held a winter-time festival in which a large phallus was erected and displayed. After competitions were held to see who could empty their jug of wine the quickest, a procession from the sea to the city was held with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and maenads (nymphs), which were often paired together. At the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,"]

The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of ivy and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The main purveyors of the Dionysus fertility cult "These drunken devotees of Dionysus," wrote Boorstin, "filled with their god, felt no pain or fatigue, for they possessed the powers of the god himself. And they enjoyed one another to the rhythm of drum and pipe. At the climax of their mad dances the maenads, with their bare hands would tear apart some little animal that they had nourished at their breast. Then, as Euripides observed, they would enjoy 'the banquet of raw flesh.' On some occasions, it was said, they tore apart a tender child as if it were a fawn'"μ

One time the maenads got so involved in what they were doing they had to be rescued from a snow storm in which they were found dancing in clothes frozen solid. On another occasion a government official that forbade the worship of Dionysus was bewitched into dressing up like a maenad and enticed into one of their orgies. When the maenads discovered him, he was torn to pieces until only a severed head remained."

See Separate Article: DIONYSUS CULT europe.factsanddetails.com

Bacchanal by Nicolas Poussin

Coming of Age Celebrations in Ancient Rome

According to Encyclopedia of Religion The cult within the familia, the extended Roman family placed under the unrestricted authority of the pater familias ("father of the family" or the "owner of the family estate"). The day of birth (dies natalis) and the day of purification (dies lustricus : the ninth day for boys, the eighth for girls, when the infant received its name) were family feasts. In the atrium of the family home, the infant would acquire the habit of honoring the household gods (the lar familiaris and the di penates). [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The allusion made in the Aulularia (v. 24s) by Plautus to a young daughter who every day would bring "some gift such as incense, wine, or garlands" to the lar familiaris ( guardian household deities) shows that personal devotion was not unknown in Rome. Livy (26.19.5) cites a more illustrious example of this kind about P. Cornelius Scipio, the future conqueror of Hannibal. "After he received the toga virilis, he undertook no action, whether public or private, without going right away to the Capitolium. Once he reached the sanctuary, he remained there in contemplation, normally all alone in private for some time." (It is true that a rumor attributed divine ancestry to Scipio, something he very carefully neither confirmed nor denied; see above).

The taking of the toga virilis, or pura (as opposed to the toga praetexta, bordered with a purple ribbon and worn by children), generally took place at age seventeen during the feast of the Liberalia on March 17. Before this point, the puer (boy) offered his bulla (a golden amulet) to the lar familiaris. From then on, he was a iuvenis, and he would go to the Capitolium to offer a sacrifice and leave an offering in the sanctuary of the goddess Juventus (Iuventas). Girls would offer dolls and clothing on the day of their wedding.

Another family feast honored the father of the family on his birthday; for reasons of convenience the commemoration and party seems to have frequently been moved to the next calends or ides. A warm atmosphere brought together the whole family, including the servants, at least twice a year. On March 1, the feast of the Matronalia, mothers of families would make their way up the Esquiline to the temple of Juno Lucina, whose anniversary it was. Together with their husbands they prayed "for the safeguarding of their union" and received presents. They then prepared dinner for their slaves. Macrobius (Saturnalia 1.12.7), who mentions this custom, adds that on December 17, the feast of the Saturnalia, it was the masters' turn to serve their slaves, unless they preferred to share dinner with them (Saturnalia 1.7.37). It is characteristic of the gendered perspective of the Romans that the "male" Saturnalia developed into a carnival lasting for several days, characterized by an exchange of gifts, as well as excessive drinking.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024