Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

POPULATION OF ANCIENT ROME

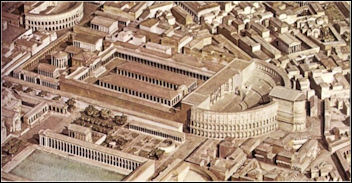

densely populated Rome Demographic studies suggest a population peak from 70 million to more than 100 million. Each of the three largest cities in the Empire — Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch — was almost twice the size of any European city at the beginning of the 17th century. Historian Kyle Harper has estimated the population was around 75 million and an average population density of about 20 people per square kilometer at its peak, with a high rate of urbanization. During the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, the population of the city of Rome is conventionally estimated at one million inhabitants. Historian Ian Morris said no other city in Europe of the Middle East would have as many again until the 19th century. [Source Wikipedia]

Rome was the first city to have a million people — by A.D. 1. The world population was around 170 million at the time of the birth of Jesus. In A.D. 100 it had risen to around 180 million. By 190 it rose to 190 million. Four fifths of the world's population lived under the Roman, Chinese Han and Indian Gupta empires at this time

Rome regularly took a census. This was used to figure out the status of citizens and figure out taxes, budgets and troop strength. Rome had a very low birth rate. This was partly the result of birth control and perhaps the result of , infanticide and miscarriages and sterility caused by lead poisoning.

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Demography and the Graeco-Roman World: New Insights and Approaches”

by Claire Holleran and April Pudsey (2011) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Roman People” by Allen M. Ward, Fritz M. Heichelheim, Cedric A. Yeo Amazon.com;

“Abortion in the Ancient World” by Konstantinos Kapparis (2002) Amazon.com;

“Earliest Italy: An Overview of the Italian Paleolithic and Mesolithic by Margherita Mussi Amazon.com;

“Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings” by Jean Manco (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic: Relations and Descent” by Alasdair Whittle, Joshua Pollard (2023) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Indo-Europeans” by J. P. Mallory (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“Romana: The Origins and Deeds of the Roman People” by Jordanes Jordanis Amazon.com;

“Aeneid” (Penguin Classics) by Virgil (19 BC) Amazon.com

“Livy: The Early History of Rome, Books I-V” (Penguin Classics)

by Titus Livy , Aubrey de Sélincourt , et al. (2002) Amazon.com

“Mediterranean Timescapes: Chronological Age and Cultural Practice in the Roman Empire”by Ray Laurence, Francesco Trifilò Amazon.com;

“Central Italy: An Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric, Villanovan, Etruscan, Samnite, Italiote and Roman Remains and the Ancient Road Systems” by R. F. Paget (1973) Amazon.com;

“The Demography of Roman Italy: Population Dynamics in an Ancient Conquest Society 201 BCE–14 CE” by Saskia Hin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Demography and Roman Society” by Professor Tim G. Parkin (1992) Amazon.com;

“Peasants, Citizens and Soldiers: Studies in the Demographic History of Roman Italy 225 BC–AD 100" by Luuk de Ligt (2012) Amazon.com;

“Peasants and Slaves: The Rural Population of Roman Italy (200 BC to AD 100) by Alessandro Launaro (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Resilience of the Roman Empire: Regional Case Studies on the Relationship Between Population and Food Resources” by Dimitri Van Limbergen, Sadi Maréchal, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Settlement, Urbanization, and Population” (Oxford Studies on the Roman Economy, Reprint) by Alan Bowman and Andrew Wilson (2012) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

Genetic Studies Reflect Rome’s Diversity

In a study published in Science in November 2019, researchers from Stanford and Italian universities said populations from ancient Romes’s earliest eras and from after the Western empire's decline in the A.D. 4th Century genetically resembled other Western Europeans. But during the imperial period in between, Romans had more in common with populations from Greece, Syria and Lebanon. The study was is based on genome data of 127 individuals from 29 archaeological sites in and around Rome, spanning nearly 12,000 years of Roman prehistory and history. [Source: AFP, November 7, 2019]

AFP reported: “The earliest sequenced genomes, from three individuals living 9,000 to 12,000 years ago, resembled other European hunter-gatherers at the time. Starting from 9,000 years ago, the genetic makeup of Romans again changed in line with the rest of Europe following an influx of farmers from Anatolia or modern Turkey. Things started to change however from 900 B.C. to 200 B.C., as Rome grew in size and importance, and the diversity shot up from 27 B.C. to 300 CE, when the city was the capital to an empire of 50 million to 90 million people, stretching from North Africa to Britain to the Middle East.

“Of the 48 individuals sampled from this period, only two showed strong genetic ties to Europe. The genetic "diversity was just overwhelming," added Ron Pinhasi of the University of Vienna, who extracted DNA from the skeletons' ear bones. After the empire split into two parts with the eastern capital in Constantinople (now Istanbul), Rome's diversity decreased once more. "The genetic information parallels what we know from historical and archaeological records," said Kristina Killgrove, a Roman bioarchaeologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who wasn't involved in the study.

“Jonathan Pritchard, a population geneticist at Stanford University who sequenced and analyzed the DNA, said mass migration is sometimes thought to be a new phenomenon. "But it's clear from ancient DNA that populations have been mixing at really high rates for a long time," he added.

Ancient Roman Census

The Romans conducted censuses every five years, calling upon every man and his family to return to his place of birth to be counted in order to keep track of the population. Historians believe that it was started by the Roman king Servius Tullius in the 6th century BC, when the number of arms-bearing citizens was counted at 80,000. The census played a crucial role in the administration of the peoples of an expanding Roman Empire, and was used to determine taxes. It provided a register of citizens and their property from which their duties and privileges could be listed. [Source: UK government]

Who were counted in the Roman census? How important was the identity of those looking at the census for the interpretation of the census process? Those are the two related central questions of the project The Roman census: counting and identity. A correct interpretation of the census figures is important for anyone who wants to learn more about the population development of the Roman Empire and of pre-industrial societies in general. Since the 19th century, it has usually been assumed that at least all adult male citizens were counted. But this interpretation is controversial. The model from which it derives seems to force us to choose between a Roman population which is either smaller or larger than can reasonably be expected. Furthermore, it is not consistent with the information we have about the census ceremony from ancient Roman sources. [Source: Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research]

According to the Data Administration Newsletter: “The Romans decided that they wanted to tax everyone in the Roman empire. But in order to tax the citizens of the Roman empire the Romans first had to have a census. The Romans quickly figured out that trying to get every person in the Roman empire to march through the gates of Rome in order to be counted was an impossibility. There were people in North Africa, in Spain, in Germany, in Greece, in Persia, in Israel, and so forth. Not only were there a lot of people in far away places, trying to transport everyone on ships and carts and donkeys to and from the city of Rome was simply an impossibility. [Source:Data Administration Newsletter]

dates were consumed to avoid pregnancy

“So the Romans realized that creating a census where the processing (i.e., the counting, the taking of the census) was done centrally was an impossibility. The Romans solved the problem by creating a body of “census takers”. The census takers were organized in Rome and then were sent all over the Roman empire and on the appointed day a census was taken. Then, after taking the census, the census takers headed back to Rome where the results were tabulated centrally.

“In such a fashion the work being done was sent to the data, rather than trying to send the data to a central location and doing the work in one place. By distributing the processing, the Romans solved the problem of creating a census over a large diverse population. Many people don’t realize that they are very familiar with the Roman census method and don’t know it. You see there once was a story about two people – Mary and Joseph – who had to travel to a small city – Bethlehem – for the taking of a Roman census. On the way there Mary had a little baby boy – named Jesus – in a manger. And the shepherds flocked to see this baby boy. And Magi came and delivered gifts. Thus born was the religion many people are familiar with – Christianity. The Roman census approach is intimately entwined with the birth of Christianity.”

Growth of Rome in the Ages of Caesar and Augustus

From the beginning of the first century B.C. to the middle of the first century A.D. the republic of Rome swelled to a point where her cohesion was in danger of being undermined and her food supply of breaking down. After the Social War in 91 B.C. an influx of refugees caused a sudden leap in numbers similar to that of fifteen years before, when the flood of Greek refugees from Asia Minor raised Athens to the rank of a great European capital. Faced by provinces and an Italy torn between the democratic government of Rome and the armies mobilised against that government by the senatorial aristocracy, the censors of 86 B.C. were obliged to abandon the attempt to make the usual general census of all citizens of the empire, and proceeded instead to catalogue the different categories of population who were herded together in the city. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” By Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

If it is true, as Lucan's commentator asserts, that when-Pompey took charge of the Annona in September, 57 B.C., he succeeded in getting the grain needed to feed a minimum of 486,000 people. After the triumph of Julius Caesar in 45 B.C. the population made another upward bound. The fact itself cannot be doubted, though, for lack of figures we cannot make an exact estimate of the increase; instead of the 40,000 whom Cicero mentions in his In Verrem as receiving free grain in 71 B.C., Caesar in 44 B.C. admitted no less than 150,000 to the free distribution. Moreover, as Censor Morum, he standardised the accidental procedure of the censors of 86 B.C.

The advance in numbers continued under the principate of Augustus. The available data combine to force us to conclude that the inhabitants of Rome must have reached nearly a million. First, we note the quantity of grain which the Annona had to store each year for the support of the population: Aurelius Victor tells us that 20,000,000 modii (1,698,000 hectolitres) were supplied by Egypt, and Josephus records that Africa furnished twice that amount in all, therefore, 60,000,000 modii?* Allowing an average yearly consumption of 60 modii (5.094 hectolitres) per head, this would represent 1,000,000 recipients.

Secondly, we have Augustus' own declaration in his Res Gcstae that when he was invested for the twenty-second time with the tribunicia potestas and for the twelfth time with the consular dignity, that is to say, in the year 5 B.C., he gave 60 denarii to each of the 320,000 citizens composing the urban plebs. Now, according to the words which the emperor deliberately employed, this distribution was confined to adult males the Latin text specifies viritim, the Greek translation XOCT' av&pa. It excluded, therefore, all women and girls and all boys under eleven. Taking the average proportion established in our time by the actuaries between men, women, and children, this yields a Roman population of at least 675,000 cives. To this we must add a garrison of 12,000 men who lived in Rome but did not partake in the congiaria, the host of noncitizens (peregrini), and another item, more important than either, the slaves. The words of Augustus himself thus lead us to calculate the total population of Rome at close to a million, if indeed it did not exceed that figure.

Lastly, we have the statistics included in the Regionaries of the fourth century A.D. These compel us to assess still higher the figure for the second century, a time when, as we have seen, the population of Rome vigorously increased. Adding up, region by region, the dwelling-houses of the Urbs as catalogued in the Notitia, we get the two totals: 1,782 domus and 44,300 insulae; but both the summary of the Notitia and Zacharias record 1,797 domus and 46,602 insulae.

Birth Control and Contraceptives in the Greco-Roman World

There is some evidence that the Romans used oiled animal bladders as condom-like sheaths. Roman women were told sperm be could expelled by coughing, jumping and sneezing after intercourse, and repeated abortions produced sterility.

According to historians, demographic studies suggest the ancients attempted to limit family size. Greek historians wrote that urban families in the first and second centuries B.C. tried to have only one or two children. Between A.D. 1 and 500, it was estimated the population within the bounds of the Roman Empire declined from 32.8 million to 27.5 million (but there can be all sorts of reason for this excluding birth control).

Birth control methods in ancient Greece included avoiding deep penetration when menstruation was "ending and abating" (the time Greeks thought a woman was most fertile); sneezing and drinking something cold after having sex; and wiping the cervix with a lock of fine wool or smearing it with salves and oils made from aged olive oil, honey, cedar resin, white lead and balsam tree oil. Before intercourse women tried applying a perceived spermicidal oil made from juniper trees or blocking their cervix with a block of wood. Women also ate dates and pomegranates to avoid pregnancy (modern studies have shown that the fertility of rats decreases when they ingest these foods).

Women in Greece and the Mediterranean were told that scooped out pomegranates halves could be used as cervical caps and sea sponges rinsed in acidic lemon juice could serve as contraceptives. The Greek physician Soranus wrote in the 2nd century A.D. : "the woman ought, in the moment during coitus when the man ejaculates his sperm, to hold her breath, draw her body back a little so the semen cannot penetrate into the uteri, then immediately get up and sit down with bent knees, and this position provoke sneezes."

Valuable Contraceptive Plant

In the seventh century B.C., Greek colonists in Libya discovered a plant called silphion , a member of the fennel family which also includes asafoetida , one of the important flavorings in Worcester sauce. The pungent sap from silphion, the ancient Greeks found, helped relieve coughs and tasted good on food, but more importantly it proved to be an effective after-intercourse contraceptive. A substance from a similar plant called ferujol has been shown in modern clinical studies to be 100 percent successful in preventing pregnancy in female rats up to three days after coitus. [Source: John Riddle, J. Worth Estes and Josiah Russell, Archaeology magazine, March/April 1994]

silphion

Known to the Greeks as silphion and to the Romans as silphium, the plant brought prosperity to the Greek city-state of Cyrene. Worth more than is weight on silver, it was described by Hippocrates, Diosorides and a play by Aristophanes. Sixth century B.C. coins depicted women touching the silphion plant with one hand and pointing at their genitals with the other. The plant was so much in demand in ancient Greece it eventually became scarce, and attempts to grow it outside of the 125-mile-long mountainous region it grew in Libya failed. By the 5th century B.C., Aristophanes wrote in his play The Knights , "Do you remember when a stalk of silphion sold so cheap?" By the third or forth century A.D., the contraceptive plant was extinct.

Abortions in the Greco-Roman World

Abortions were performed in ancient times, says North Carolina State history professor John Riddle, and discussions about featured many of the same arguments we hear today. The Greeks and Romans made a distinction between a fetus with features and one without features. The latter could be aborted without having to worry about legal or religious reprisals. Plato advocated population control in the ideal city state and Aristotle suggested that "if conception occurs in excess...have abortion induced before sense and life have begun in the embryo."

The Stoics believed the human soul appeared when first exposed to cool air, and the potential for a soul existed at conception. Hippocrates warned physicians in his oath not to use one kind of abortive suppository, but the statement was misinterpreted as a blanket condemnation of all of abortion. John Chrystom, the Byzantine bishop of Constantinople compared abortion to murder in A.D. 390, but a few years earlier Bishop Gregory of Nyssa said the unformed embryo could not be considered a human being. [Riddle has written a book called “Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance”]

silphion symbol

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: According to Plautus (died 185 B.C.) , abortion was a likely action for a pregnant prostitute to take, either -Ovid (born 43 B.C.) suggested - by drinking poisons or by puncturing with a sharp instrument called the foeticide, the amniotic membrane which surrounds the foetus. Procopius of Caesarea (A.D. 500-554) states emphatically that when she was a prostitute, Empress Theodora knew all the methods which would immediately provoke an abortion (Anecd. 9.20). [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3]

“Didascalia Apostolorum (around A.D. 230) condemned both abortion and infanticide: 'You will not kill the child by abortion and you will not murder it once it is born'. In 374, a decree of Emperors Valentinian I and Valens forbade infanticide on pain of death (Cod. Theod. 9.14.1). Nevertheless, the practice which had been common in the Roman period, continued. That is why the Tosephta (Oholoth 18.8) repeated in the fourth century the warning made by the Mishna in the second century: 'The dwelling places of Gentiles are unclean... What do they [the rabbis] examine? The deep drains and the foul water'. This implied that the Gentiles disposed of their aborted foetuses in the drains of their own houses.” ~

Infanticide in Ancient Rome

Infanticide and abortion were common practice in the Roman Empire that produced a disproportionally large male population as the victims were often girls. One husband wrote his pregnant wife: "If, as could well happen, you give birth, if it’s a male, let it be — if it's a female, cast it out."

"Exposing" newborns was a decision often made by the father. Under Roman law a father could commit infanticide as long as he invited five neighbors to examine the body before it was left to die. Infants were left to die of exposure or flung on garbage heaps simply for being sickly or female or an extra mouth to feed. In one study of 600 upper class families only six had more than one daughter. Women sometimes made arrangements to have exposed children rescued and brought up in secret. Other times poor families grabbed infanticide victims and raised them as slaves.

Excavations of an ancient sewer under a Roman bathhouse in Ashkleon in present-day Israel revealed the remains of more than 100 infants thought be unwanted children from the brothel. They infants had been thrown into a gutter along with animal bones, pottery shards and a few coins and are thought to have been unwanted because of the way they were disposed. DNA tests revealed that 74 percent of the victims were male. Usually unwanted children were girls.

Pat Smith, a physical archaeologist at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, told National Geographic, “We know that infanticide was widely practiced by the Greeks and Romans. It was regarded as the parents’ right if they didn’t want a child. Usually they killed girls. Boys were considered more valuable — as heirs for support in old age. Girls were sometimes viewed as burdens, especially if they needed a dowry to marry.”

Augustus's Marriage Reforms

In attempt to boost the declining birth rate Augustus, in the A.D. first century, offered tax breaks for large families and cracked down on abortion. He imposed strict marriage laws and changed adultery from an act of indecency to an act of sedition, decreeing that a man who discovered his wife’s infidelity must turn her in or face charges himself. Adulterous couples could have their property confiscated, be exiled to different parts of the empire and be prohibited from marrying one another. Augustus passed the reforms because he believed that too many men spent their energy with prostitutes and concubines and had nothing for their wives, causing population declines.

Under Augustus, women had the right to divorce. Husbands could see prostitutes but not keep mistresses, widows were obligated to remarry within two years, divorcees within 18 months. Parents with three or more children were given rewards, property, job promotions, and childless couples and single men were looked down upon and penalized . The end result of the reforms was a skyrocketing divorce rate.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024