Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire / Christianized Roman Empire / Christianity and Judaism in the Roman Empire / Early History of Christianity

CONSTANTINE AND CHRISTIANITY

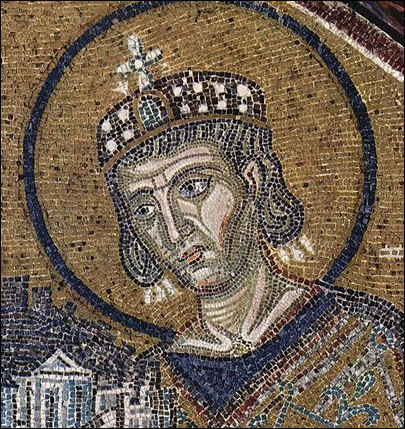

Constantine Byzantine mosaic Constantine (A.D. 312-37) is generally known as the “first Christian emperor.” The story of his miraculous conversion is told by his biographer, Eusebius. It is said that while marching against his rival Maxentius, he beheld in the heavens the luminous sign of the cross, inscribed with the words, “By this sign conquer.” As a result of this vision, he accepted the Christian religion; he adopted the cross as his battle standard; and from this time he ascribed his victories to God, and not to himself. The truth of this story has been doubted by some historians; but that Constantine looked upon Christianity in an entirely different light from his predecessors, and that he was an avowed friend of the Christian church, cannot be denied. His mother, Helena, was a Christian, and his father, Constantius, had opposed the persecutions of Diocletian and Galerius. He had himself, while he was ruler in only the West, issued an edict of toleration (A.D. 313) to the Christians in his own provinces. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Holland Lee Hendrix told PBS: “Constantine's conversion to Christianity, I think, has to be understood in a particular way. And that is, I don't think we can understand Constantine as converting to Christianity as an exclusive religion. Clearly he covered his bases. I think the way we put it in contemporary terms is "Pascal's Wager" — it's another insurance policy one takes out. And Constantine was a consummate pragmatist and a consummate politician. And I think he gauged well the upsurge in interest and support Christianity was receiving, and so played up to that very nicely and exported it in his own rule. But it's clear that after he converted to Christianity he was still paying attention to other deities. We know this from his poems and we know it from other dedications as well. [Source: Holland Lee Hendrix, President of the Faculty Union Theological Seminary, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“But what's important to understand and appreciate about Constantine is that Constantine was a remarkable supporter of Christianity. He legitimized it as a protected religion of the empire. He patronized it in lavish ways. ... And that really is the important point. With Constantine, in effect the kingdom has come. The rule of Caesar now has become legitimized and undergirded by the rule of God, and that is a momentous turning point in the history of Christianity. ...

“To appreciate the remarkable dramatic evolution that had occurred in so short a period, one might counterpose the image of Pliny and his courtroom under the Emperor Trajan — sending Christians off to their execution simply for being called Christians — to the majesty of Constantine presiding over the great gathering of bishops that he had called to resolve particular questions. The Imperium on the one hand being used clearly to extinguish a religious movement. The Imperium on the other hand being used clearly to undergird and support a religious movement, the same religious movement in so short a period of time.”

See Separate Articles: CONSTANTINE THE GREAT (AD 312-37): HIS LIFE, RISE TO POWER AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ; CONSTANTINE THE GREAT (AD 312-37) AS RULER OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com ; PRO-CHRISTIAN LAWS AND REFORMS ENACTED BY CONSTANTINE THE GREAT africame.factsanddetails.com ; CHRISTIANITY IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE AFTER CONSTANTINE africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Websites and Resources: Christianity Britannica on Christianity britannica.com//Christianity ; History of Christianity history-world.org/jesus_christ ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ;Wikipedia article on Christianity Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/christ.htm ; Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ;

Early Christianity: Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; PBS Frontline From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Early Christian Art oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth212/Early_Christian_art ; Early Christian Images jesuswalk.com/christian-symbols ; Early Christian and Byzantine Images belmont.edu/honors/byzart2001/byzindex

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom” by Peter J. Leithart (2010) Amazon.com;

“The History of the Church: From Christ to Constantine” (Penguin Classics)

by Eusebius , Andrew Louth , et al. (1990) Amazon.com;

“Constantine the Great” by Michael Grant Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Great: And the Christian Revolution” by G. P. Baker Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Emperor” (Reprint Edition) by David Potter Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine” by Noel Lenski Amazon.com;

“The Age of Constantine the Great” by Jacob Burckhardt, Moses Hadas Amazon.com;

“Constantine at the Bridge” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2021) Amazon.com;

“The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine” by Timothy D. Barnes (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Age of Martyrs: Christianity from Diocletian (284) to Constantine (337)”

by Giuseppe Ricciotti and Anthony Bull (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World” by Catherine Nixey (2017) Amazon.com

“The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire” by Alan Kreider Amazon.com ;

“The Church and the Roman Empire (301–490): Constantine, Councils, and the Fall of Rome” by Mike Aquilina Amazon.com ;

“The Seven Ecumenical Councils” by Henry R Percival, Philip Schaff, et al Amazon.com ;

“The General Councils: A History of the Twenty-One Church Councils from Nicaea to Vatican II by Christopher M. Bellitto Amazon.com ;

“When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers” by Marcellino D'Ambrosio Amazon.com ;

“Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years” by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Walter Dixon, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Eusebius on Constantine

Was Constantine a Christian or a Pagan?

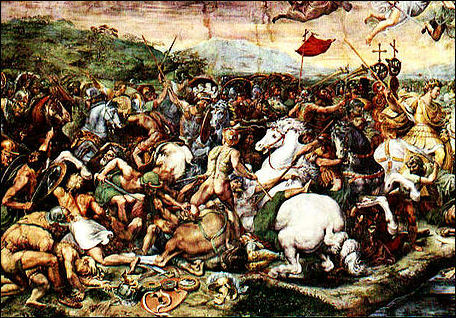

Raphael's Constantine at Milvian Bridge Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: “When he became sole emperor in 324 AD, he rewrote his own history with the help of Christian authors. He actively promoted the Christian Church, though he was baptised into the faith only on his death bed. Throughout his life he also acknowledged Sol Invictus - the 'Unconquered Sun' - as a god. He may have been a true convert, or he may have used the Church as a strong unifying force - the debate continues.” [Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe wrote for the BBC: “One of the supposed watersheds in history is the ‘conversion’ of the emperor Constantine to Christianity in, or about, 312 AD. Historians have marvelled at this idea. Emperors had historically been hostile or indifferent to Christianity. How could an emperor subscribe to a faith which involved the worship of Jesus Christ - an executed Jewish criminal? This faith was also popular among slaves and soldiers, hardly the respectable orders in society. [Source: Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The story of Constantine’s conversion has acquired a miraculous quality, which is unsurprising from the point of view of contemporary Christians. They had just emerged from the so-called ‘Great Persecution’ under the emperor Diocletian at the end of the third century. The moment of Constantine’s conversion was tied by two Christian narrators to a military campaign against a political rival, Maxentius. The conversion was the result of either a vision or a dream in which Christ directed him to fight under Christian standards, and his victory apparently assured Constantine in his faith in a new god. |::|

“Constantine’s ‘conversion’ poses problems for the historian. Although he immediately declared that Christians and pagans should be allowed to worship freely, and restored property confiscated during persecutions and other lost privileges to the Christians, these measures did not mark a complete shift to a Christian style of rule. Many of his actions seemed resolutely pagan. Constantine founded a new city named after himself: Constantinople. Christian writers played up the idea that this was to be a 'new Rome', a fitting Christian capital for a newly Christian empire. |But they had to find ways to explain the embarrassing fact that in this new, supposedly Christian city, Constantine had erected pagan temples and statues. |::|

How Sincere was Constantine's Christianization?

Hans A. Pohlsander of SUNY wrote: “When Diocletian and Maximian announced their retirement in 305, the problem posed by the Christians was unresolved and the persecution in progress. Upon coming to power Constantine unilaterally ended all persecution in his territories, even providing for restitution. His personal devotions, however, he offered first to Mars and then increasingly to Apollo, reverenced as Sol Invictus. [Source: Hans A. Pohlsander, SUNY Albany, Roman Emperors ]

Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe wrote for the BBC: ““How should we characterise Constantine’s religious convictions? The differing but related accounts of his miraculous conversion suggest some basic spiritual experience which he interpreted as related to Christianity. His understanding of Christianity was, at the stage of his conversion, unsophisticated. He may not have understood the implications of converting to a religion which expected its members to devote themselves exclusively to it. However, what was certainly established by the early fourth century was the phenomenon of an emperor adopting and favouring a particular cult. What was different about Constantine’s ‘conversion’ was merely the particular cult to which he turned – the Christ-cult – where previous emperors had sought the support of pagan gods and heroes from Jove to Hercules. | [Source: Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

How complete and how sincere was Constantine's conversion? Professor Allen D. Callahan told PBS: “[To answer that] is absolutely impossible. This is one of the worst abuses of arm chair psychology in the historiography of early Christianity. Constantine continued to behave like a pagan well after his so-called conversion. It didn't stop him from killing people. It didn't stop him from doing all of the kinds of unsavory things that Roman emperors were wont to do. But again, I think from an institutional perspective, the change that was inaugurated by, let's say, the re-orientation of his personal commitments... signaled the reconfiguration of relations between institutions in the late Roman Empire. When we go farther than that, we go to Eusebius and other apologists for Constantine and we know what they really want to do. They want to put his best face forward even if they've got to put a lot of makeup on it. ... We understand Eusebius' motivations, but I think the real important thing there is that conversion experience, how we understand that that particular individual signals something for the culture and the institutions of late antiquity and that's the most important aspect of that one single conversion experience for us.” [Source: Allen D. Callahan, Associate Professor of New Testament, Harvard Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Battle of the Milvian Bridge,

In 310, Constantine decided he was going to take Rome. He lead a small army to the Alps for an important battle outside Rome on the Tiber River against his rival Maxentius, the emperor of Rome.

Constantine dreamed that Jesus told him to take the cross as his standard. Constantine ordered that new standards be made up, emblazoned with the cross. The next morning at the Battle of Milvian Bridge, on October 28, 312 he scored a victory against great odds against Maxentius, whose forces were swept into the Tiber, where Maxentius drowned. Constantine may well have thought a divine power was guiding his fortune, for if Maxentius had stayed within the massive walls of Rome and forced Constantine to lay siege, the outcome of the contest could have been different. But Maxentius chose to do battle outside the walls.

Constantine attributed his military victory to the Christian faith and entered Rome with Maxentius's head on a pike. He erected the triumphal Arch of Constantine in Rome and took control of the western half of the Roman Empire. Maxentius had been the strongest member of the Tetrarchy. By 323, Constantine had unified the Roman Empire and brought it under his control by defeating another rival, the eastern co-emperor Licinius.

Constantine's Conversion to Christianity

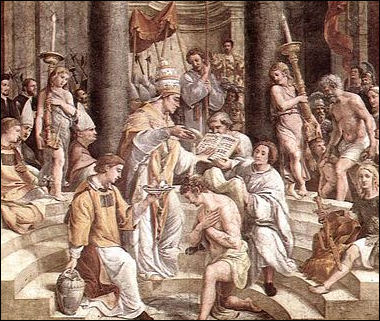

Raphael's Baptism of Constantine J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Tradition has it that before the night before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, Constantine had a vision that resulted in his conversion to Christianity. The earlier and simpler version comes from Lactantius, writing within four years of the event, but in Eusebius' Life of Constantine, published shortly after Constantine's death, there is a more elaborate version, which Eusebius claims to have heard from Constantine himself. His account relates that "about noon, when the day was already beginning to decline, he saw with his own eyes flaming cross above the sun with the words " In hoc signo vinces " ("in this sign you will conquer"). The words " In hoc signo vinces " are featured on the label of Pall Mall cigarettes. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Hans A. Pohlsander of SUNY wrote: “Lactantius, whom Constantine appointed tutor of his son Crispus and who therefore must have been close to the imperial family, reports that during the night before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge Constantine was commanded in a dream to place the sign of Christ on the shields of his soldiers. Twenty-five years later Eusebius gives us a far different, more elaborate, and less convincing account in his Life of Constantine. When Constantine and his army were on their march toward Rome - neither the time nor the location is specified - they observed in broad daylight a strange phenomenon in the sky: a cross of light and the words "by this sign you will be victor" (hoc signo victor eris or ). During the next night, so Eusebius' account continues, Christ appeared to Constantine and instructed him to place the heavenly sign on the battle standards of his army. The new battle standard became known as the labarum. [Source: Hans A. Pohlsander, SUNY Albany, Roman Emperors ]

“Whatever vision Constantine may have experienced, he attributed his victory to the power of "the God of the Christians" and committed himself to the Christian faith from that day on, although his understanding of the Christian faith at this time was quite superficial. It has often been supposed that Constantine's profession of Christianity was a matter of political expediency more than of religious conviction; upon closer examination this view cannot be sustained. Constantine did not receive baptism until shortly before his death (see below). It would be a mistake to interpret this as a lack of sincerity or commitment; in the fourth and fifth centuries Christians often delayed their baptisms until late in life.”

Eusebius on The Conversion of Constantine

On the Conversion of Constantine, Eusebius wrote: Chapter XXVII: “Being convinced, however, that he needed some more powerful aid than his military forces could afford him, on account of the wicked and magical enchantments which were so diligently practiced by the tyrant, he sought Divine assistance, deeming the possession of arms and a numerous soldiery of secondary importance, but believing the co-operating power of Deity invincible and not to be shaken. He considered, therefore, on what God he might rely for protection and assistance. While engaged in this enquiry, the thought occurred to him, that, of the many emperors who had preceded him, those who had rested their hopes in a multitude of gods, and served them with sacrifices and offerings, had in the first place been deceived by flattering predictions, and oracles which promised them all prosperity, and at last had met with an unhappy end, while not one of their gods had stood by to warn them of the impending wrath of heaven; while one alone who had pursued an entirely opposite course, who had condemned their error, and honored the one Supreme God during his whole life, had formal I him to be the Saviour and Protector of his empire, and the Giver of every good thing. [Source: “Library of Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers,” 2nd series (New York: Christian Literature Co., 1990), Vol I, 489-9, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“Reflecting on this, and well weighing the fact that they who had trusted in many gods had also fallen by manifold forms of death, without leaving behind them either family or offspring, stock, name, or memorial among men: while the God of his father had given to him, on the other hand, manifestations of his power and very many tokens: and considering farther that those who had already taken arms against the tyrant, and had marched to the battle-field under the protection of a multitude of gods, had met with a dishonorable end (for one of them had shamefully retreated from the contest without a blow, and the other, being slain in the midst of his own troops, became, as it were, the mere sport of death (4) ); reviewing, I say, all these considerations, he judged it to be folly indeed to join in the idle worship of those who were no gods, and, after such convincing evidence, to err from the truth; and therefore felt it incumbent on him to honor his father's God alone.

Constantine's conversion Chapter XXVIII: Accordingly he called on him with earnest prayer and supplications that he would reveal to him who he was, and stretch forth his right hand to help him in his present difficulties. And while he was thus praying with fervent entreaty, a most marvelous sign appeared to him from heaven, the account of which it might have been hard to believe had it been related by any other person. But since the victorious emperor himself long afterwards declared it to the writer of this history, when he was honored with his acquaintance and society, and confirmed his statement by an oath, who could hesitate to accredit the relation, especially since the testimony of after-time has established its truth? He said that about noon, when the day was already beginning to decline, he saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription, CONQUER BY THIS. At this sight he himself was struck with amazement, and his whole army also, which followed him on this expedition, and witnessed the miracle.

Chapter XXIX: He said, moreover, that he doubted within himself what the import of this apparition could be. And while he continued to ponder and reason on its meaning, night suddenly came on ; then in his sleep the Christ of God appeared to him with the same sign which he had seen in the heavens, and commanded him to make a likeness of that sign which he had seen in the heavens, and to use it as a safeguard in all engagements with his enemies.

Chapter XXX: At dawn of day he arose, and communicated the marvel to his friends: and then, calling together the workers in gold and precious stones, he sat in the midst of them, and described to them the figure of the sign he had seen, bidding them represent it in gold and precious stones. And this representation I myself have had an opportunity of seeing.

Chapter XXXI: Now it was made in the following manner. A long spear, overlaid with gold, formed the figure of the cross by means of a transverse bar laid over it. On the top of the whole was fixed a wreath of gold and precious stones; and within this, the symbol of the Saviour's name, two letters indicating the name of Christ by means of its initial characters, the letter P being intersected by X in its centre: and these letters the emperor was in the habit of wearing on his helmet at a later period. From the cross-bar of the spear was suspended a cloth, a royal piece, covered with a profuse embroidery of most brilliant precious stones; and which, being also richly interlaced with gold, presented an indescribable degree of beauty to the beholder. This banner was of a square form, and the upright staff, whose lower section was of great length, bore a golden half-length portrait of the pious emperor and his children on its upper part, beneath the trophy of the cross, and immediately above the embroidered banner. The emperor constantly made use of this sign of salvation as a safeguard against every adverse and hostile power, and commanded that others similar to it should be carried at the head of all his armies.

Chapter XXXII: “These things were done shortly afterwards. But at the time above specified, being struck with amazement at the extraordinary vision, and resolving to worship no other God save Him who had appeared to him, he sent for those who were acquainted with the mysteries of His doctrines, and enquired who that God was, and what was intended by the sign of the vision he had seen. They affirmed that He was God, the only begotten Son of the one and only God: that the sign which had appeared was the symbol of immortality, and the trophy of that victory over death which He had gained in time past when sojourning on earth. They taught him also the causes of His advent, and explained to him the true account of His incarnation. Thus he was instructed in these matters, and was impressed with wonder at the divine manifestation which had been presented to his sight. Comparing, therefore, the heavenly vision with the interpretation given, he found his judgment confirmed; and, in the persuasion that the knowledge of these things had been imparted to him by Divine teaching, he determined thenceforth to devote himself to the reading of the Inspired writings. Moreover, he made the priests of God his counselors, and deemed it incumbent on him to honor the God who had appeared to him with all devotion. And after this, being fortified by well-grounded hopes in Him, he hastened to quench the threatening fire of tyranny.”

Implications of Constantine's Conversion

Constantine's conversion

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Constantine entered Rome a victor, and began a policy of generosity to the church. He gave Pope Melchiades the Lateran Palace, which had belonged to his wife, Fausta, and only a fortnight after the Battle at the Milvian Bridge, on November 9, we have the traditional dedication date of the first church he built in Rome, the Lateran Basilica. The Roman Senate, which was to be a stronghold of paganism until the century's end, dedicated an arch in Constantine's honor (315–316) and its attic bore an inscription attributing his victory neutrally to "instinctu divinitatis " (the prompting of divinity). By the same year, the basilica which Maxentius had been building for secular use, a massive fragment of which still stands in the Roman Forum, had been dedicated to Constantine and in it was a great statue of him holding a spear shaped like a cross. Constantine's Christianity can hardly be doubted, but he treated pagans with tact. The majority of the population was still pagan. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Professor Allen D. Callahan told PBS:“The benefits of imperial patronage were enormous. There are a lot of questions about the profundity of his conversion experience, since he still seems to carry on pretty much like a pagan, even after the vision on the Milvian Bridge. But I think all those matters are matters of the apologies that are written for Constantine afterwards. What's important is that he signals a kind of detente that's reached between the church as a force to be reckoned within imperial society and the Roman state. ... I think that these were two projects in which a lot of people were very, very heavily involved, and they are on a collision course with each other and some kind of resolution has to be accomplished by somebody, otherwise they're going to destroy each other or compromise each other's integrity. And so, Constantine is a historical point man with respect to the relation of the Roman state to the growing Christian movement as an institutional force in late antique society. [Source: Allen D. Callahan, Associate Professor of New Testament, Harvard Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“There's an imperial underwriting of pilgrimage and pilgrimage sites, and so a lot of money goes to refurbishing those pilgrimage sites that exist and making them bigger and better and even greater and grander attractions, and creating pilgrimage sites where none existed previously. ...[This] sends a kind of cultural shockwave to the entire society. Now, pilgrimage is a very important activity among Roman elites and others who now identify themselves as Christians — to go to the holy places and see the holy things. Christianity becomes another kind of institutional force after this detente, so to speak. ...

“From the beginning of the Jesus movement, there was always the problem of negotiating the proper relation between the members of the movement, who owed their allegiance to a different Lord, and the powers of the state — the state which, incidentally, killed Jesus. [There is] the story of the coin that's produced for Jesus and they say, "Shall we pay tribute to Caesar?" and Jesus says,"Well, show me a coin. Whose face is on it? Caesar's. We'll render unto Caesar that which is Caesar's and render unto God that which is God's." [This is] Jesus' famous non-answer to the question of that relation between the Jesus movement and the powers of the state. In early Byzantine political ideology, after the detente between Rome and Jerusalem, after the so-called conversion of Constantine, it's possible to have two thrones set side by side. In one, the emperor sits. tTe other is left empty because there, Christ, the ruler of the world, is presumed to be reigning and the emperor is seen as a vice-regent of Christ. This resolution, this answer to that nagging problem, is possible after Constantine's [conversion].

Constantine Makes Constantinople the Capital of Christianity

Constantine moved the main capital of the Roman empire from Rome to Byzantium, a former Greek city on the Bosporus. With the move from Rome to Byzantium (later Constantinople and Istanbul) the pagan Roman empire was transformed into the Christian Byzantine empire. Although the city was formally dedicated in A.D. 330, Constantine began making plan for the move soon after he became Supreme Leader in 324. With little delay, Constantine began the construction of two major churches — Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) and Hagia Eirene (Holy Peace) — in Constantinople, without . The foundation of a third, the Church of the Holy Apostles, is generally attributed to him. Unlike Old Rome, which was filled with pagan monuments and institutions, the New Rome was essentially a Christian capital , although not all traces of its pagan past had been eliminated. [Source: Hans A. Pohlsander, SUNY Albany, Roman Emperors]

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: There was a city on the site before Constantine's new foundation, Byzantium, which was founded by the Greek city-state of Megara in 659 B.C. according to tradition. Unlike Rome, it had few monuments of its pagan past. There were temples to Artemis, Aphrodite, and the sun god Helios on its acropolis, which survived until the emperor Theodosius I turned them to secular uses, but Constantinople was to be a Christian city filled with churches. The Great Palace that Constantine began in the southeast section of the city was to grow into an immense complex of pavilions, churches — at least 20 of them — residential quarters and reception halls, and it was joined by a private passageway to the imperial loge in the Hippodrome that flanked the palace. In the middle of the Forum, oval-shaped and markedly different from the traditional rectangular forum of a Roman town with a temple of Jupiter at one end, stood a great porphyry column 100 feet high, bearing a statue of Constantine with the radiate crown usually associated with the Sun God: indeed, it may have been a recycled statue of Apollo. This new foundation was to be a worthy capital. The grain ships which had carried their cargoes from Egypt to Rome were diverted gradually to Constantinople, and Rome was left to get its grain from Africa and Sicily. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

For the patriarch, Constantine built a noble patriarchal church, Hagia Eirene, and his son constantius ii added a better one, hagia sophia, served by the same clergy. The bishop of Byzantium had been only a suffragan bishop of the see of Heraclea Pontica, but now he became the patriarch of Constantinople, with the prestige of the new capital behind him: the third canon of the Second Ecumenical Council of 381 which met at Constantinople was to state that the bishop possessed "prerogatives of honor after the Bishop of Rome, because Constantinople is New Rome." The pope in old Rome heard the news without pleasure and would not recognize the patriarch's claims. Nor did they sit well with the see of St. Mark in Alexandria which claimed second place itself.

A few pagan temples were closed. A temple of Aphrodite at Efge in Lebanon, where transvestites and women prostituted themselves, was razed. At Heliopolis (Ba'albek) where there were only women prostitutes, Constantine urged restraint on the people and built a church, but otherwise did not interfere. The town of Hispellum in Italy petitioned him towards the end of his life to allow the building of a temple dedicated to his family, and he consented with the proviso that there be no sacrifices (C.I.L. xi, 5265). He confiscated treasure from temples, some of which housed a wealth of dedications, no doubt to the success of his currency reform. He issued a gold coin, the solidus, which was valued at 72 to a pound of gold, and which was used until the fall of the Byzantine empire. He may have banned pagan sacrifices, though the law has not survived. His son Constantius II did pass such a ban (Cod. Theod. 16.10.2) and refers to one his father passed. Sacrifices were at the core of paganism and the pagan cults would be severely damaged if they were prohibited.

The church enjoyed favor. Most clergy supported themselves partly by farming or crafts, and Constantine ruled that they should be exempt from compulsory labor (sordida munera ). (In 330, rabbis and heads of synagogues were also freed from compulsory public services involving physical labor). Constantius II extended the privileges of the clergy to their wives, children, and servants. But most of all Constantine shows his favor by building and endowing churches. In Rome his greatest church was St. Peter's, built over a necropolis where tradition had it that St. Peter was buried. In Jerusalem he built the church of the Holy Sepulchre, and Constantine's mother, St. helena, also built churches on the Mount of Olives and at Bethlehem. They set a pattern: in Late Antiquity private euergetism was to be directed towards building and endowing churches, and the secular public buildings it had once sustained were left to crumble.

Constantine Becomes Involved in Church Disputes

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Having accepted Christianity, Constantine found himself immersed without delay in the disputes of the Church. In Carthage, the Catholics were under attack by the followers of a certain donatus. In the persecution which had only recently ended, some clergy had surrendered the Scriptures, and the Donatists took a hard line, arguing that these traditores who had handed over sacred books should not be readmitted to he church. They appealed to Constantine, who referred the question to a caucus of bishops in Rome, and when the Donatists refused to accept its verdict, to a council with wider representation at Arles. The Donatist arguments failed again, whereupon the Donatists demanded to know what business the matter was of the emperor's. Constantine attempted a round of persecution to bring the Donatists to heel, but without success, and the Donatist schism endured well into the next century. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Once Constantine eliminated Licinius, he encountered a more serious contention centering on the doctrine of Arius, a presbyter in Alexandria who argued that in the Trinity the Son must be secondary to the Father. To solve this dispute, Constantine in A.D. 325 convened a council of bishops at nicaea, the first of seven recognized ecumenical councils of the church. The minutes of this council have not survived, and we are dependent on the eyewitness account of eusebius of caesarea in his Life of Constantine (3.7–14). Many of the bishops had experienced persecution less than a couple decades before, and it must have been a heady experience for them to meet with the emperor and have him defer to their opinions. Yet Constantine took an active role: he seems himself to have suggested the controversial nub of the Nicene Creed which emerges from the Council, that the Son was of joint substance (homoousios ) with the Father. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Constantine Christianizes the Roman Empire

Constantine was accepted as a Christian after the Battle of Milvian Bridge and is regarded as the first Christian emperor. He wasn't baptized, however, until he was on his deathbed and called for a priest, shouting “Let there be no ambiguity." In March 313, Constantine issued his famous Edict of Milan which gave every person the right to practice any religion they wanted. With the edict Constantine formally recognized Christianity and put an end to the persecution of Christians.

![]()

Bulgarian icon of

Constantine and Helena In 324, Constantine made Christianity the state religion: stating there was "No distinction between realm of Caesar and the realm of God." Under Constantine, pagan temples were expropriated, their treasuries were used to build churches and support clergy, and laws were adjusted for Christian ethics.

Before Constantine's time Christians practiced their faith in private. Under Constantine, suddenly they could practice their faith openly. Constantine went on a church building spree, constructing churches from Jerusalem to Rome. His grandest church was the original St. Peters which was destroyed by fire.

Before Constantine, the attitude of the Roman government toward Christianity varied at different times. At first indifferent to the new religion, it became hostile and often bitter during the “period of persecutions” from Nero to Diocletian. But finally under Constantine Christianity was accepted as the religion of the people and of the state. A large part of the empire was already Christian, and the recognition of the new religion gave stability to the new government. Constantine, however, in accepting Christianity as the state religion, did not go to the extreme of trying to uproot paganism. The pagan worship was still tolerated, and it was not until many years after this time that it was proscribed by the Christian emperors. For the purpose of settling the disputes between the different Christian sects, Constantine called (A.D. 325) a large council of the clergy at Nice (Nicaea), which decided what should thereafter be regarded as the orthodox belief. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Harry Sidebottom wrote in The Telegraph: Constantine’s vision and conversion weren’t all that unusual. The emperor Aurelian had seen a vision of Sol Invictus before the Battle of Emesa (AD 272), and previously Constantine himself had had a vision of Apollo. What was unusualwas the longevity of Constantine (died AD 337), and his sons (Constantius II, died AD 361). Half a century of imperial patronage and coercion would entrench the particular type of Christianity favoured by Constantine and his family. [Source: Harry Sidebottom, The Telegraph, February 25, 2024]

Christianity Advances Under Constantine

Constantine became like a Pope. He called the first general ecumenical council, in Nicaea in A.D. 325, to settle questions of doctrine. The most important decision was the adoption of Nicene creed: the assertion that the denial of Christ's divinity was a heresy. This became the basis of all church doctrine from that time forward. Anyone who departed from the creed was branded a heretic. See Christianity

St. Helena, the mother of Constantine, became one of the most cherished saints in the Greek Orthodox church. On her first pilgrimage to the Holy Land she came back with the True Cross, Christ's crown of thorns and the lance used to pierce his skin before his crucifixion. And if that wasn't enough she identified Christ's tomb, which had been covered over by a temple dedicated to Aphrodite. The site is now occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem."

Under Constantine, Christians who deviated from official church doctrine were branded as heretics. They were given no support, were punished with penalties and were ordered to stop meeting.

After Constantine died in 337, the Roman Empire was divided up among his sons. Christianity spread gradually but inexorably through the Roman Empire and beyond its borders. Paganism was banned at the end of 4th century and restrictions were placed on Judaism. The power and the wealth of the church grew quickly with the help of faithful Christians who donated their land and other possessions. By the beginning of the 6th century Christianity had 34 million followers. They made up half of the Roman Empire.

Constantine's Imperial Christianity

Constantine and Helena

Professor Shaye I.D. Cohen told PBS: “One of the first things Constantine does, as emperor, is start persecuting other Christians. The Gnostic Christians are targeted...and other dualist Christians. Christians who don't have the Old Testament as part of their canon are targeted. The list of enemies goes on and on. There's a kind of internal purge of the church as one emperor ruling one empire tries to have this single church as part of the religious musculature of his vision of a renewed Rome. And it's with this theological vision in mind that Constantine not only helps the bishops to iron out a unitary policy of what a true Christian believes, but he also, interestingly, turns his attention to Jerusalem, and rebuilds Jerusalem just as a righteous king should do. [Source: Shaye I.D. Cohen, Samuel Ungerleider Professor of Judaic Studies and Professor of Religious Studies Brown University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“But what Constantine does is take the city, which was something of a backwater, and he begins to build beautiful basilicas and architecturally ambitious projects in the city itself. The sacred space of the Temple Mount he abandons. It's not reclaimable. And what he does is [to] religiously relocate the center of gravity of the city around the places where Christ had suffered, where he had been buried, or where he [had] been raised. So that in the great basilicas that he built, Constantine has a new Jerusalem, that's splendid and beautiful and... his reputation as an imperial architect resonates with great figures in biblical history like David and Solomon. In a sense, Constantine is a non-apocalyptic Messiah for the church.

“The bishops are terribly grateful for this kind of imperial attention. It's not the western Middle Ages. The lines of power are unambiguous. Constantine is absolutely the source of authority. And there's no question about that. But the bishops are able to take advantage of Constantine's mood and his curious intellectual interest in things like Christology and the Trinity and Church organization. They're able to have bibles copied at public expense. They are finally able to have public Christian architecture and big basilicas. So there's a comfortable symbiotic relationship between the empire and the church, one that, in a sense, is what defines the cultural powerhouse of Europe and the West.

First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325

In A.D., 325, the Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea (present-day Iznik In Turkey), inaugurating the ecumenical movement. Called by Constantine to combat heresy and settle questions of doctrine, it attracted thousands of priests, 318 bishops, two papal lieutenants and the Roman Emperor Constantine himself. The attendees discussed the Holy trinity and the eventual linkage of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, argued whether Jesus was truly divine or just a prophet (he was judged divine), and decided that Easter would be celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox.

The early councils were shaped largely by Christian scholars from Alexandria and their views were in line with modern Coptic doctrine that the God and Christ are of the same essence and that Christ's divinity and humanity are unified.

Constantine made a grand entrance at the council. According to one witness he “proceeded through the midst of the assembly” and acted like a Pope. The greatest debate was between Arius, a priest from Alexandria, who argued that Christ was not the equal of God but was created by him, and Athanasius, the leader of the bishops to the west, who claimed that the Father and Son, where distinct, but hatched from the same substances and thus were equal. Arus's argument was rejected in part because it opened to the door to polytheism and a doctrine was codified that stated Christ was “begotten not made” and that God and Christ were “of the same stuff."

The Council of Nicaea gave us the Roman version of Christianity rather the Nestorian. The most important decision was the rejection of Arius's arguments and the adoption of Nicene creed: the assertions that Christ's divinity, the Virgin Birth and the Holy Trinity were truths and the denial of Christ's divinity was a heresy. This became the basis of all church doctrine from that time forward. Anyone who departed from the creed was branded a heretic.

See Separate Article: ECUMENICAL COUNCILS africame.factsanddetails.com

Constitutum Constantini (Donation of Constantine) and Its Unraveling as Forgery

The Pope's authority over all of Europe is based the Constitutum Constantini (the Donation of Constantine), a 3,000-word documented purportedly written by Constantine between A.D. 315 and 325 that legalized Christianity and gave the See of Rome and the pope spiritual power over the entire world in addition to political power over Europe. The document was not made public until the ninth century when it was used as evidence in dogma debates when the Christian church split into the Catholic church and Eastern Orthodox Church.

In the A.D. 8th century Pope Stephen II and the military leader Pepin (king of the Franks and father of Charlemagne) gained control of huge chunk of land in central Italy, that included Rome and Ravenna, by using the Constitutum Constantini . The chunk of land, known as the Patrimony of St. Peter, was ruled by the popes for most of the next 11 centuries.

The Constitutum Constantini (the Donation of Constantine) was later revealed to be, in the words of Voltaire, the "boldest and the most magnificent forgery." One of the documents flaws was that it gave Rome authority in New Rome (Constantinople) at least a decade before the city was founded.

In 1440,the Constitutum Constantini was labeled a fake by Lorenzo Valla who was called into settle a dispute between King Alfonos and Pope Eugenius IV over who had secular authority over Italy. Valla showed the Constitutum Constantini was a fake. An authority on Latin, Valla pointed out that a diadem in Constantine's time was not a gold crown as the the Constitutum Constantini claimed but was coarse cloth and the word "tiara" was not even in use at the time the document was said to have been written. A number of other words in it were not used in Constantine's time.

Valla was later convicted of heresy for pointing out the "Apostle's Creed" could not have been composed by the Twelve Apostles. He was convicted on eight counts and probably would have been burned at the stake were it not for his patron King Alfonso. Valla's criticism of the Bible itself were not well received either.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024