Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire

SEVERANS

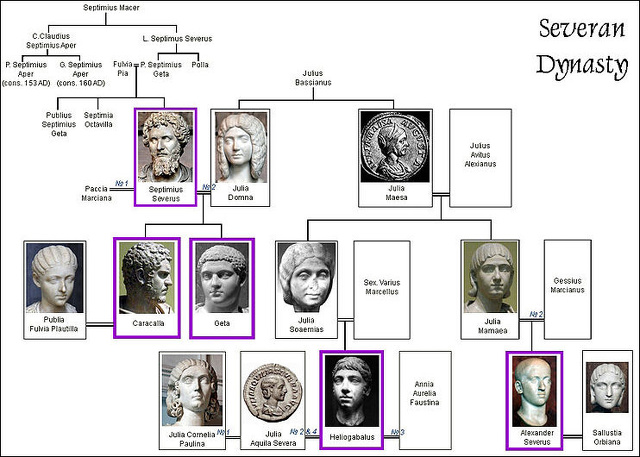

Septimius Severus and family The Severan dynasty was a Roman imperial dynasty, which ruled the Roman Empire between A.D. 193 and 235. The dynasty was founded by the general Septimius Severus, who rose to power as the victor of the 193–197 civil war. Although Septimius Severus successfully restored peace following a period of upheaval in the late A.D. 2nd century, the dynasty was characterized by highly unstable family relationships, as well as constant political turmoil that helped produce the Crisis of the Third Century. The Severans were one of the last lineages of the Principate founded by Augustus. [Source: Wikipedia]

Severan Dynasty (193–235 A.D.)

Septimius (193–211 A.D.)

Caracalla (with Geta, 211–12 A.D.) (211–17 A.D.)

Macrinus (217–18 A.D.)

Diadumenianus (218 A.D.)

Elagabalus (218–22 A.D.)

Alexander Severus (222–35 A.D.)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 193 A.D., Septimius Severus seized Rome and established a new dynasty. He rested his authority more overtly on the support of the army and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions, thereby broadening imperial power throughout the empire. The Severan dynasty gave rise to the imperial candidates of Syrian background. Caracalla abolished all distinctions between Italians and provincials. Following his reign, however, military anarchy led to a succession of short reigns and eventually the rule of the soldier-emperors (235–84 A.D.). [Source: Christopher Lightfoot, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire” by Michael Grant (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Praetorian Guard: A History of Rome's Elite Special Forces” by Sandra Bingham (2012) Amazon.com

“Severan Culture” (Reprint) by Simon Swain Amazon.com;

Rome, The Late Empire: Roman Art A.D. 200-400" by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, translated by Peter Green (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Year of Five Emperors: Part 1: Pertinax” by Robert N Eckert (2023) Amazon.com;

“Commodus (The Damned Emperors)” by Simon Turney (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Year of Five Emperors: Part 2: Severus” by Robert N Eckert (2023) Amazon.com;

“Septimius Severus” by Anthony R. Birley (1999) Amazon.com;

“Emperor Septimius Severus: The Roman Hannibal” by Dr. Ilkka Syvänne (2023) Amazon.com;

“Septimius Severus & the Roman Army” by Michael Sage (2021) Amazon.com;

“The African Emperor: Septimius Severus” by Anthony Richard Birley (1988) Amazon.com;

“Caracalla: A Military Biography” by Ilkka Syvänne (2020) Amazon.com;

“Baths of Caracalla: Guide” by Gail Swirling (2008) Amazon.com;

“Decoration and Display in Rome's Imperial Thermae: Messages of Power and their Popular Reception at the Baths of Caracalla” by Maryl B. Gensheimer (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Baths of Caracalla” by Piranomonte Marina Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine” by Patricia Southern (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Triumph of Empire: The Roman World from Hadrian to Constantine” by Michael Kulikowski (2016) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C. - A.D. 476" by Michael Grant (1997) Amazon.com;

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World”

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Severan Dynasty (193–235)

Septimius Severus (ruled A.D. 193-211), the founder of the Severan dynasty, was a senator from Libya who became Rome's first African emperor. With the rise of the African Severan dynasty, many of Rome's senators were from Africa. Septimius Severus was succeeded by Geta (ruled A.D. 209-212, co-emperor with Septimius Severus and Caracallas 209-211) followed by Caracalla alone (211-212)

Baths of Caracalla

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The Severan dynasty comprised the relatively short reigns of Septimius Severus (r. 193–211 A.D.), Caracalla (r. 211–17 A.D.), Macrinus (r. 217–18 A.D.), Elagabalus (r. 218–22 A.D.), and Alexander Severus (r. 222–35 A.D.).Its founder, Septimius Severus, was a member of a leading native family of Leptis Magna in North Africa who allied himself with a prominent Syrian family by his marriage to Julia Domna. Their union, which gave rise to the imperial candidates of Syrian background, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus, testified to the broad political franchise and economic development of the Roman empire. It was Septimius Severus who erected the famous triumphal arch in the Roman Forum, an important vehicle of political propaganda that proclaimed the legitimacy of the Severan dynasty and celebrated the emperor's victories against Parthia in a lavishly sculpted historical narrative. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Severan Dynasty (193–235)", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

“As in most artistic achievements under the Severans, the monumental reliefs show a decisive break with classicism that presaged Late Antique and Byzantine works of art. At Leptis Magna, he renovated and embellished a number of monuments and built a grandiose new temple-forum-basilica complex on an unparalleled scale that befitted the birthplace of the new emperor. Septimius cultivated the army with substantial remuneration for total loyalty to the emperor and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions. In this way, he successfully broadened the power of the imperial administration throughout the empire. By abolishing the regular standing jury courts of Republican times, he was likewise able to transfer power to the executive branch of the government. \^/

“His son, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, nicknamed Caracalla, obliterated all distinctions between Italians and provincials, and enacted the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 A.D., which extended Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Caracalla was also responsible for erecting the famous baths in Rome that bear his name. Their design served as an architectural model for later monumental public buildings. He was assassinated in 217 A.D. by Macrinus, who then became the first emperor who was not a senator. The imperial court, however, was dominated by formidable women who arranged the succession of Elagabalus in 218 A.D., and Alexander Severus, the last of the line, in 222 A.D. In the last phase of the Severan principate, the power of the Senate was finally revived and a number of fiscal reforms were enacted. The fatal flaw of its last emperor, however, was his failure to control the army, eventually leading to mutiny and his assassination. The death of Alexander Severus signaled the age of the soldier-emperors and almost a half-century of civil war and strife. \^/

Roman Empire at the Time of the Severans

It can be argued that the fall of the republic and the establishment of the empire were generally positive things that greatly benefitted to Rome. In place of a century of civil wars and discord which closed the republic, we see more than two centuries of internal peace and tranquillity. Instead of an oppressive and avaricious treatment of the provincials, we see a treatment which is with few exceptions mild and generous. Instead of a government controlled by a proud and selfish oligarchy, we see a government controlled, generally speaking, by a wise and patriotic prince. From the accession of Augustus to the death of Marcus Aurelius (31 B.C. —A.D. 180), a period of two hundred and eleven years, only three emperors who held power for any length of time—Tiberius, Nero, and Domitian—are known as tyrants; and their cruelty was confined almost entirely to the city, and to their own personal enemies. The establishment of the empire, we must therefore believe, marked a stage of progress and not of decline in the history of the Roman people. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Roman Empire in AD 210

But in spite of the fact that the empire met the needs of the people better than the old aristocratic republic, it yet contained many elements of weakness, Some say the Roman people themselves possessed the frailties of human nature, and the imperial government was not without the imperfection of all human institutions. The decay of religion and morality, it has been argued, was a fundamental cause of their weakness and ruin, with this including the selfishness of classes; the accumulation of wealth, not as the fruit of legitimate industry, but as the spoils of war an of cupidity; the love of gold and the passion for luxury; the misery of poverty and its attendant vices and crimes; the terrible evils of slave labor; the decrease of the population; and the decline of the patriotic spirit. These were moral diseases, which could hardly be cured by any government. \~\

One of the great defects of the imperial government was that its power rested with the military basis, and not upon the rational will of the people. It is true that many of the emperors were popular and loved by their subjects. But behind their power was the army, which knew its strength, and strongly asserted its claims to the government. The period extending from the death of Marcus Aurelius to the accession of Diocletian (A.D. 180-284) has therefore been aptly called “the period of military despotism.” It was a time when the emperors were set up by the soldiers, and generally cut down by their swords. During this period of one hundred and four years, the imperial title was held by twenty-nine different rulers, some few of whom were able and high-minded men, but a large number of them were weak and despicable. Some of them held their places for only a few months. The history of this time contains for the most part only the dreary records of a declining government. There are few events of importance, except those which illustrate the tyranny of the army and the general tendency toward decay and disintegration. \~\

Year of the Five Emperors and How the Severans Came to Power

The Year of the Five Emperors was A.D. 193, in which five men claimed the title of Roman emperor: 1) Pertinax, 2) Didius Julianus, 3) Pescennius Niger, 4) Clodius Albinus, and 5) Septimius Severus. This year started a period of civil war when multiple rulers vied for the chance to become emperor. [Source Wikipedia]

The Roman Empire was arguably at its nadir at this time and came close to breaking up. That it did not do so shows the extent to which the idea of a Roman Empire had been accepted by the peoples of the Mediterranean. The political unrest began with the murder of Emperor Commodus on New Year's Eve 192. Once he was out of the way, Pertinax was named emperor, but he immediately got on the wrong side of his bodyguards, the 12,000-strong Praetorian Guard, when he attempted to initiate reforms. They then plotted his assassination. After serving only 86 days as Emperor, Pertinax was killed while trying to reason with the mutineers by two members of the Praetorian Guard.

The historian William Stearns Davis wrote: “ the Praetorian Guards (elite army members) murdered the Emperor Pertinax, who had striven to reduce them to discipline. The sale of the purple which followed forms one of the most fearful and dramatic incidents in the history of the Empire, illustrating: 1) how completely the guardsmen had lost all sense of decency, discipline, and patriotism; 2) how the idea that all things were purchasable for money had possessed the men of the Empire. It ought to be said that the Praetorians were an especially pampered corps, and probably the rest of the army was less corrupted. [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

Pertinax was replaced by Didius Julianus (See Below), who purchased the title from the Praetorian Guard. Didius Julianus held his ill-gotten power only from March 28th, 193 A.D., to June 1st of the same year, being deposed and slain when Septimius Severus and the valiant Danube legions marched on Rome to avenge Pertinax. The ringleaders of the Praetorians were executed; the rest of the guardsmen dishonorably discharged and banished from Italy.

After Didius Julianus was executed on June 1, he was succeeded by Septimius Severus who was declared Caesar by the Senate, but Pescennius Niger in a hostile takeover attempt also declared himself emperor. This triggered the civil war between Niger and Severus; both gathered troops and fought throughout the territory of the empire. During this time, Severus allowed Clodius Albinus, whom he suspected of being a threat, to be co-Caesar so that Severus did not have to preoccupy himself with imperial governance. This move allowed him to concentrate on waging the war against Niger. Most historians count Severus and Clodius Albinus as two emperors, though they ruled simultaneously and that thats how you end up with five emperors The Severan dynasty was created out of the chaos of A.D. 193.

Didius Julianus — the Man Who Bought the Roman Empire

After Pertinax's death no one was sure how to fill the vacant seat. One guard had the bright idea of auctioning off leadership to the world's most powerful empire in the world to the highest bidder. Only two competed in the auction, which was won by Didius Julianus who paid 300 million sesterces for the privilege. He proved to be unpopular with both the Senate and the public, and after only 66 days in office he was beheaded by the army of a general who was outraged by the auction. [People's Almanac]

Marcus Didius Julianus served as Roman emperor from March to June 193, during the Year of the Five Emperors. Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Didius Julianus served as governor of several provinces and was immensely wealthy. According to the second-century Roman historian Cassius Dio, the Praetorians announced after killing Pertinax that they would sell the throne to the man who paid the highest price, and Julianus won the subsequent bidding war by offering 25,000 sesterces to every Praetorian soldier — the equivalent of several years' pay. After accepting his offer, the Praetorians threatened the Roman senate until they proclaimed Julianus emperor. [Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, August 15, 2022]

But he didn't enjoy the throne for very long. The Roman people, who knew that he had purchased the emperorship, openly opposed the new emperor, and on one occasion pelted him with stones. Eventually, three different generals in the Roman provinces each declared themselves emperor, and they began advancing on Rome with their armies to enforce their claims. Julianus and the Praetorian Guard fought off one of the generals, Septimius Severus, and tried to negotiate a power-sharing deal with him; but eventually the Praetorians and the senate abandoned Julianus; they proclaimed Severus emperor and ordered Julianus to be executed, just 66 days after he'd ascended the throne.

How Didius Julianus Bought the Roman Empire at Auction

Didius Julianus

On how Didius Julianus bought the Roman Empire at auction, Herodian of Syria (3rd Cent. A.D.) wrote in “History of the Emperors”: “When the report of the murder of the Emperor Pertinax spread among the people, consternation and grief seized all minds, and men ran about beside themselves. An undirected effort possessed the people---they strove to hunt out the doers of the deed, yet could neither find nor punish them. But the Senators were the worst disturbed, for it seemed a public calamity that they had lost a kindly father and a righteous ruler. Also a reign of violence was dreaded, for one could guess that the soldiery would find that much to their liking. When the first and the ensuing days had passed, the people dispersed, each man fearing for himself; men of rank, however, fled to their estates outside the city, in order not to risk themselves in the dangers of a change on the throne. But at last when the soldiers were aware that the people were quiet, and that no one would try to avenge the blood of the Emperor, they nevertheless remained inside their barracks and barred the gates; yet they set such of their comrades as had the loudest voices upon the walls, and had them declare that the Empire was for sale at auction, and promise to him who bid highest that they would give him the power, and set him with the armed hand in the imperial palace. [Source: Herodian of Syria, “History of the Emperors” II.6ff, William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“When this proclamation was known, the more honorable and weighty Senators, and all persons of noble origin and property, would not approach the barracks to offer money in so vile a manner for a besmirched sovereignty. However, a certain Julianus---who had held the consulship, and was counted rich---was holding a drinking bout late that evening, at the time the news came of what the soldiers proposed. He was a man notorious for his evil living; and now it was that his wife and daughter and fellow feasters urged him to rise from his banqueting couch and hasten to the barracks, in order to find out what was going on. But on the way they pressed it on him that he might get the sovereignty for himself, and that he ought not to spare the money to outbid any competitors with great gifts to the soldiers.

“When he came to the wall of the camp, he called out to the troops and promised to give them just as much as they desired, for he had ready money and a treasure room full of gold and silver. About the same time too came Sulpicianus, who had also been consul and was prefect of Rome and father-in-law of Pertinax, to try to buy the power also. But the soldiers did not receive him, because they feared lest his connection with Pertinax might lead him to avenge him by some treachery. So they lowered a ladder and brought Julianus into the fortified camp; for they would not open the gates, until they had made sure of the amount of the bounty they expected.

When he was admitted he promised first to bring the memory of Commodus again into honor and restore his images in the Senate house, where they had been cast down; and to give the soldiers the same lax discipline they had enjoyed under Commodus. Also he promised the troops as large a sum of money as they could ever expect to require or receive. The payment should be immediate, and he would at once have the cash brought over from his residence. Captivated by such speeches, and with such vast hopes awakened, the soldiers hailed Julianus as Emperor, and demanded that along with his own name he should take that of Commodus. Next they took their standards, adorned them again with the likeness of Commodus and made ready to go with Julianus in procession.

“The latter offered the customary imperial sacrifices in the camp; and then went out with a great escort of the guards. For it was against the will and intention of the populace, and with a shameful and unworthy stain upon the public honor that he had bought the Empire, and not without reason did he fear the people might overthrow him. The guards therefore in full panoply surrounded him for protection. They were formed in a phalanx around him, ready to fight; they had "their Emperor" in their midst; while they swung their shields and lances over his head, so that no missile could hurt him during the march. Thus they brought him to the palace, with no man of the multitude daring to resist; but just as little was there any cheer of welcome, as was usual at the induction of a new Emperor. On the contrary the people stood at a distance and hooted and reviled him as having bought the throne with lucre at an auction.

Septimius Severus

Septimius Severus

Emperor Septimius Severus (ruled A.D. 193 - 211) became emperor after victory in a civil war. His reign is noted for the reforming of the praetorian guard, which Augustus had organized and Tiberius had encamped near the city. In place of the old body of nine thousand soldiers, Septimius organized a Roman garrison of forty thousand troops selected from the best soldiers of the legions. This was intended to give a stronger military support to the government; but in fact it gave to the army a more powerful influence in appointment of the emperors. Septimius destroyed his enemies in the senate, and took away from that body the last vestige of its authority. He was himself an able soldier and made several successful campaigns m the East. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Dr Jon Coulston of the University of St. Andrews wrote for the BBC: Septimius Severus’s “reforms were principally designed to strengthen the ruling dynasty's position. He cashiered the old 'Italian' Praetorian Guard, replacing it with men recruited from the Danubian legions which first acclaimed him emperor. He further controlled the city of Rome by stationing a newly-raised legion nearby at Albano. Severus personally led the armies of his defeated rivals against the empire's external enemies in Syria and Britain. As new provinces were established, so were new legions. Large provincial commands with three legions were divided so as to break up legionary concentrations. Military service was made more attractive by raised pay and an end to the ban on soldiers' marrying. |::|

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Septimius Severus “was a member of a leading native family of Leptis Magna in North Africa who allied himself with a prominent Syrian family by his marriage to Julia Domna. Their union, which gave rise to the imperial candidates of Syrian background, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus, testified to the broad political franchise and economic development of the Roman empire. It was Septimius Severus who erected the famous triumphal arch in the Roman Forum, an important vehicle of political propaganda that proclaimed the legitimacy of the Severan dynasty and celebrated the emperor's victories against Parthia in a lavishly sculpted historical narrative. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Severan Dynasty (193–235), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

“As in most artistic achievements under the Severans, the monumental reliefs show a decisive break with classicism that presaged Late Antique and Byzantine works of art. At Leptis Magna, he renovated and embellished a number of monuments and built a grandiose new temple-forum-basilica complex on an unparalleled scale that befitted the birthplace of the new emperor. Septimius cultivated the army with substantial remuneration for total loyalty to the emperor and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions. In this way, he successfully broadened the power of the imperial administration throughout the empire. By abolishing the regular standing jury courts of Republican times, he was likewise able to transfer power to the executive branch of the government. \^/

How Septimius Severus Established Himself as the Roman Emperor

After the reign of Commodus, the contemptible son of Marcus Aurelius, the soldiers became the real sovereigns of Rome. After Pertinax and Didius Julianus were killed three different armies—in Britain, in Pannonia, and in Syria—each proclaimed its own leader as emperor. Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211): The commander of the army in the neighboring province of Pannonia was the first to reach Rome; and was thus able to secure the throne against his rivals.

J. A. S. Evans wrote in New Catholic Encyclopedia: Decimus Clodius Albinus, put forward by the army in Britain, Gaius Pescennius Niger, backed by the Syrian legions, and Lucius Septimius Severus, supported by the legions on the Rhine and the Danube. Septimius Severus reached Rome in early June of 193 and was confirmed as princeps by the Senate. In 193 and 194 he campaigned against Niger, who was defeated and killed. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Pertinax

Albinus and Severus at first made a pact to cooperate, but after Severus disposed of Niger, he designated his own son to succeed him, thus making it clear that there would be no place for Albinus in his future plans. Albinus put up a fight, but Severus moved quickly against Albinus' forces, which were based in Lugdunum (Lyon) and defeated them in two battles. Albinus killed himself and Severus had his body thrown into the Rhine, his wife and children killed, and his supporters hunted down. With Severus the emperor emerges as autocrat. His power was rooted in the army's loyalty and he knew it: he increased the pay of the soldiers by half. When he died in 211, his last words to his sons Caracalla and Geta were "Do not quarrel with each other, enrich the soldiers and scorn everyone else."

Septimius Severus felt no great reverence for Augustan tradition and determined to found a dynasty. He assumed the persona of Marcus Aurelius' son, and made the Senate deify his "brother" Commodus. He deliberately excluded the Senate from active participation in the government, and for that matter downgraded the importance of Italy. The old praetorian guard which was still mostly Italian was disbanded and replaced with a new guard recruited from Septimius' own legions, and he appointed two new Praetorian Prefects, one of them an African. He raised three new legions after he had disposed of Albinus and put equestrian prefects in command of them, thus breaking with the Augustan tradition of choosing legates to head the legions from the ranks of the senate. Then, when he left Rome for the East to wage war on the Parthians ( A.D. 195), he left one of his new legions behind, stationed a mere 20 miles from Rome. When Severus, having defeated Parthia, annexed Upper Mesopotamia and set up a new province, he put an equestrian governor in charge of it. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Deification of Emperor Septimius Severus in A.D. 211

Describing the deification of Emperor Septimius Severus in A.D. 211, the Greek historian Herodian wrote: "It is a Roman custom to give divine status to those emperors who die with heirs to succeed them. This ceremony is called deification. Public mourning, with a mixture of festive and religious ritual, is proclaimed throughout the city, and the body of the dead is buried in the normal way with a costly funeral.

"Then they make an exact wax replica of the man, which they put on a huge ivory bed strewn with gold-threaded coverings, raised high up in the entrance to the palace. This image, in the deathly palace, rests there like a sick man...the whole Senate sitting on the left, dressed in black, while on the right are all women who can claim special honors...This continues for seven days, during each of which doctors came and approach the bed, take a look at the supposed invalid and announce a daily deterioration in his condition."

“When at last the news is given that he is dead, the end of the bier is raised on the shoulders of the noblest members of Equestrian Order and chosen young Senators, carried along the Sacred Way, and placed in the Forum Romanum...a chorus of children from the noblest and most respected families stands facing a body of women selected on merit. Each group sings hymns and songs."

Septimius Severus

“After this the bier is raised and carried outside the city walls to a square structure filled with firewood and "covered with golden garments, ivory decorations and rich pictures." On top of the structure are five more structures that are progressively smaller. “The whole thing was often five or six stories tall."

"When the bier has been taken to the second story and put inside, aromatic herbs and incense of every kind produced on earth, together with flowers, grasses and juices collected for their smell, and brought and poured in heaps...When the pile of aromatic material is very high and the whole space filled...The whole equestrian Order rides round...Chariots also circle in the same formation, the charioteers dressed in purple and carrying images with the masks of famous Roman generals and emperors."

"The heir to the throne takes a brand and sets it to every building . All the spectators crowd in and add to the flame. Everything is very easily and readily consumed...From the highest and smallest story...an eagle is released and carried up into the sky with the flames. The Romans believe the bird bears the soul of the emperor from earth to heaven. Thereafter the dead emperor is worshipped with the rest of the gods."

Army During the Severan Period

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: During the Severan period The army played a role in the transformation of Roman society. Its corps of engineers provided a pool of expertise for building roads and bridges and even purely civilian projects like amphitheaters. Until Severus' principate, legionaries could not marry, but they did form alliances with women living near their camps, and they might wed them when they retired with their gratuities and savings and settle into civilian life with their families. Their sons not infrequently followed the example of their fathers and became soldiers. Auxiliary troops received citizenship when they retired. Thus the army was constantly feeding the citizenship roll. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The office of Praetorian Prefect acquired increased importance. One prefect was commander of the armed forces in Italy, and the other was given jurisdiction in all criminal cases in Italy beyond the 100-mile radius of Rome and deputized for the princeps in hearing appeals from provincial courts. He took over the more important duties of the prefect of the grain supply (praefectus annonae ) and chaired the Consilium Principis when the princeps was absent. Because of the judicial duties attached to the Praetorian Prefect's office, we find distinguished jurists like the great Papinian appointed to the prefecture, and after Papinian lost his life for criticizing Caracalla's murder of his brother Geta, Ulpian and Paul held the office successively. Once citizenship was made universal by the Constitutio Antoniniana, Roman law applied to everyone, but from the time of the Severi we find it recognizing a distinction between citizens of higher status (honestiores ) and those of lower status (inferiores ), with more severe penalties for the same offense imposed on the inferiores. The emperor became the source of law, not only in practice, for this had arguably been true earlier, but also in theory. Ulpian put it simply, "What the emperor decides is law."

Recruits for the army now came almost exclusively from the provinces. Poor administration by provincial governors, now called praesides, was sternly punished. Wars, the increased pay for the army, and the imperial building program all increased government outlays, and Severus depreciated the denarius by a further 20 percent. The ratio of silver to base metal in the silver denarius had been drifting downwards in the second century, but under the Severi the trend gathered pace. Severus also made sweeping confiscations of the property belonging to Albinus' supporters, which was assigned to a special treasury, the res privata.

Citizens and Barbarians During the Severan Period

Geta and Caracalla

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Provincials might acquire citizenship through the generosity of emperors or patrons. Leading families in provincial cities might have citizenship conferred on them. The allure of citizenship, and the upward mobility it made possible, was one of the instruments that kept the provincials loyal. Finally, the emperor Caracalla brought the process to an end in 212 A.D. with the Constitutio Antoniniana which conferred citizenship on everyone in the empire except the dediticii : probably barbarians who were settled on deserted land in the empire. How large this group was at this point in time is not known.. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Roman society became less Roman, if we can identify citizens by their origins. By the time of the Severi, the proportion of senators of known Italian ancestry is less than half, and there was only one senatorial family that could trace its family tree back to the pre-Augustan republic. The writers Lucan, Martial, and the Senecas were all Spaniards; so were the emperors Trajan and Hadrian. Africans become prominent in the senate from the time of Hadrian. Septimius Severus was born in Lepcis Magna in modern Libya and his unlucky rival, Clodius Albinus was also an African. Severus' wife, Julia Domna, was a Syrian. By the second century's end, the legions were recruited almost entirely from the provinces. The city of Rome was still the heart of the empire, but Italy was no longer its heartland.

After Septimius Severus

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Caracalla, Geta, Macrinus, Elagabalus and Severus Alexander. Septimius' sons, Geta (211–212) and Aurelius Antoninus, better known by his nickname "Caracalla," succeeded him, but their joint rule ended when Caracalla murdered his brother and obliterated his portraits and inscriptions. Edward Gibbon, influenced by the hostility to Caracalla of our main source, Cassius Dio, called him a "monster," and he may have deserved it. He gave the army generous donatives and increased pay, and he relaxed discipline in order to curry favor. While leading an offensive against Parthia, he was assassinated by his Praetorian Prefect, Opilius Macrinus, who became emperor himself to the dismay of the Senate, for he was only an equestrian. Macrinus recognized the need to relieve the stress on the economy, and though he did not dare revoke Caracalla's pay increases to the army, he recruited new soldiers on the old pay scale of Septimius Severus, which provoked discontent. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Julia Maesa, the sister of Septimius' widow, Julia Domna, got the Syrian legions to support her grandson Varius Avitus Bassianus. He was a boy of 14, better known as Elagabalus, for he was a priest and devotee of the sun god Elagabalus that was worshipped at Emesa. Maesa launched a rumor that Bassianus had been sired by Caracalla, and he took the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. Macrinus marched out from his base at Antioch against the young pretender and was defeated. Elagabalus, however, proved incapable and his devotion to his god, whose cult he tried to introduce into Rome, shocked Roman tradition so much that his grandmother transferred her support to another grandson, Marcus Aurelius Aurelianus Alexander, son of Julia Mamaea. Elagabalus was killed and was succeeded by Alexander, who added "Severus" to his name. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Caraculla

Septimius Severus’s son and heir, the Afro-Syrian warrior Caraculla (ruled A.D. 198 - 217 ) left behind a "trail or massacre and murder" and made some noteworthy reforms. After he killed his brother Geta in a struggle for the throne, he granted citizenship and raised pay in A.D. 212 to all free (non-slave) members of the empire's population, thus requiring them to pay certain citizen taxes, and thereby strengthening the army's financial base. He built the great Baths of Caracalla, which covered 26 acres, initiated cruel proscriptions and murdered Papinian, the greatest of the Roman jurists, who refused to defend his crimes.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, nicknamed Caracalla, obliterated all distinctions between Italians and provincials, and enacted the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 A.D., which extended Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Caracalla was also responsible for erecting the famous baths in Rome that bear his name. Their design served as an architectural model for later monumental public buildings. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Severan Dynasty (193–235)", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Baths of Caracalla (on a hill not far from the Circus Maximus in Rome) was the largest baths built by the Romans. Opened in A.D. 216 and covering 26 acres, more than six time the space in St. Paul's Cathedral in London, this massive marble and brick complex could accommodate 1,600 bathersand contained playing, fields, shops, offices, gardens, fountains, mosaics, changing rooms, exercise courts, a tepidarium (warm-water bathing hall), caldarium (hot-water bathing hall), frigidarium (cold-water bathing hall), and natatio (unheated swimming pool). Shelley wrote much of “Prometheus Bound” while sitting among the ruins at Caracalla.

With the Constitutio Antoniniana, or Edict of Caracalla (A.D. 212), the Roman franchise, which had been gradually extended by the previous emperors, was now conferred to all the free inhabitants of the Roman world. The edict was issued primarily to increase tax revenue. Even so, the edict was in the line of earlier reforms and effaced the last distinction between Romans and provincials. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Caracalla was assassinated in 217 A.D. by Macrinus ((ruled A.D. 217-218), who then became the first emperor who was not a senator. After his death the emperorship was passed on to the in-laws of the late Septimius Severus.

Elagabulus and Ostrich-Brain Pies

After Macrinus, the imperial court was dominated by formidable women who arranged the succession of Elagabalus in A.D. 218. Under the youthful Elagabulus (ruled A.D. 218-222), regarded by some as the worst Roman Emperor, and Severus Alexander (ruled A.D. 222-235), the Roman Empire was for all intents and purposes run by their grandmother Julia Maesa and their mothers.

Elagabulus started dressing in drag shortly after he was named emperor. He enjoyed pretending he was a woman so much that he ordered the senate to address him as the "Empress of Rome." He once ordered 600 ostriches killed so his cooks could make him ostrich-brain pies. He made appointments by choosing men with the largest penises.

As a teenage emperor Elagabulus hosted a famous feast which featured camels feet; honeyed dormice; the brains of 600 ostriches; conger eels fattened on Christian slaves; and caviar from fish caught with emperor's private fishing fleet. Guest were also given a dish with a sauce made by a chef who had to eat nothing but that sauce if the emperor didn't like it.

Elagabulus reportedly came to the banquet on a chariot pulled by naked women and is said to have liked to mix gold and pearls with peas and rice. He ate and drank from bejeweled gold plates and goblets. Guests to his banquets were given free slaves and homes and live versions of the animals they had just eaten. His idea of practical jokes was to play a game and give the winner a prize of dead flies and drug guests wine and have them wake in a room filled with lions and leopards. These excesses exhausted Rome's treasury and Elagabulus met his end, assassinated in a latrine.

See Separate Article: ELAGABALUS — ANCIENT ROME’S WORST EMPEROR— AND HIS HEDONISM AND OSTRICH-BRAIN PIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Alexander Severus

Alexander Severus

After the brief reign of Macrinus, and the longer reign of the monster Elagabalus, the most repulsive of all the emperors, the throne was occupied by Alexander Severus (A.D. 222-235), generally regarded as an able leader. In a corrupt age, he stood out as a voice of reason and goodness. It is said that he set up in his private chapel the images of those whom he regarded as the greatest teachers of mankind, including Abraham and Jesus Christ. He tried as best he could to follow the example of the best of the emperors. He selected as his advisers the great jurists, Ulpian and Paullus. The most important event of his reign was his successful resistance to the Persians, who had just established a new monarchy on the ruins of the Parthian kingdom (A.D. 226). The Severan Dynasty ended when Severus Alexander was murdered. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In the last phase of the Severan principate, the power of the Senate was finally revived and a number of fiscal reforms were enacted. The fatal flaw of its last emperor, however, was his failure to control the army, eventually leading to mutiny and his assassination. The death of Alexander Severus signaled the age of the soldier-emperors and almost a half-century of civil war and strife. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Severan Dynasty (193–235)", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Severus Alexander emerges dimly from the sources, but he appears an attractive figure. Julia Maesa soon died, so his mother, Julia Mamaea, acted as his advisor. But he was faced with a difficult situation. In the east, the Parthian dynasty, the Arsacids, was overthrown in 226 by Ardashir, founder of a new Iranian dynasty, the Sassanids, and Ardashir, taking the name Artaxerxes, was crowned king of a revived Persian Empire. In 230, Ardashir invaded Mesopotamia and threatened Syria. Alexander apparently mounted a successful defense. He returned to Rome and then on to the Rhine to meet a German threat. There he was murdered by his troops who were, it seems, disgusted when Alexander tried to defend the frontier by diplomacy and paying indemnities to the Germans. His successor, Maximinus the Thracian (235–238), was a great brute of massive size and barbarity, who visited neither Rome nor Italy during his three-year reign and introduced a half century of anarchy. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024