Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire

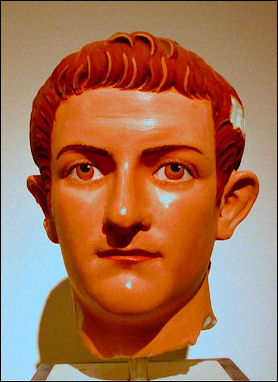

CALIGULA (RULED FROM A.D. 37-41)

Caligula Caligula (born A.D. 12, ruled A.D. 37-41) was the Roman Empire’s third emperor and ranks with Nero as one of the world’s most hated — and remembered — rulers. Caligula had a great passion for women, gladiator games, chariot racing, theatrical performances, ships and violence. He liked to watch people being tortured and executed and murdered his brother along with countless others. He lasted only four years in power before he was assassinated. Some scholars dismiss accounts of Caligula's excesses as exaggerated by historians and a public that didn't like him. Other than the great ship he built there is no archaeological evidence that he spent more or was more wasteful than other emperors.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Tiberius bequeathed a great surplus to his successor, Caligula, whose enormously extravagant games and spectacles eventually emptied the imperial treasury. In matters of government, Caligula favored a monarchy of Hellenistic type and accepted elaborate honors in Rome and in the provinces. The dissemination of imperial portraiture in the provinces, in sculpture, gems, and coins, was the chief means of political propaganda in the Roman empire, and all of the Julio-Claudians subscribed to the basic imperial image established by Augustus. Even Caligula, who was obsessed with his own appearance, adhered to this formula. His reign of extravagance, oppression, and treason trials ended in his assassination in 41 A.D. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org ]

Caligula was one of the first emperors with truly unlimited power. He often referred to himself as a god and even appointed his horse as a priest. Caligula also appeared in public dressed in women’s clothing, and reportedly told his guards to use call-signs that were clearly feminine. It has been said that the reign of Caligula, which was fortunately very brief, shows to us the perils inherent in a despotic form of government that permitted a madman to rule the civilized world. The Roman Empire had no provision by which any prince could be held responsible, either to law or to reason. A cruel tyrant could revel in blood, or a maniac could indulge in the wildest excesses without restraint. The only limit to such a despotism was assassination; and by this severe method the reign of Caligula was brought to an end. [Sources: Andrew Handley, Listverse, February 8, 2013; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Caligula: A Biography” by Aloys Winterling, Glenn W. Most, Paul Psoinos (2015) Amazon.com;

“Caligula: The Abuse of Power” by Anthony A. Barrett, a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia; Amazon.com;

Film: Caligula (Uncut Edition) by Penthouse with Malcolm McDowell as Caligula and Peter O'Toole as Tiberius and John Gielgud as one of Caligula's advisors. The film featured a decapitating machine and lots of naked writhing bodies Amazon.com;

“Caligula: The Mad Emperor of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2019) Amazon.com;

“Evil Roman Emperors: The Shocking History of Ancient Rome's Most Wicked Rulers from Caligula to Nero and More by Phillip Barlag (2021) Amazon.com;

“Infamous Roman Emperors: Conquest, Sabotage, and Betrayal in the Roman Empire” by August Mead (2023) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Caesars” (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius (121 AD) Amazon.com

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Annals” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Caligula's Early Life

Caligula — Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus — was born on August 13, A.D. 12. The son of Germanicus, one of Rome’s most revered leaders and popular Roman general, and Agrippina the Elder, the granddaughter of Augustus, Caligula was born into the first ruling family of the Roman Empire, conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Two years after Caligula's birth, Germanicus' uncle and adoptive father, Tiberius, succeeded Augustus as emperor of Rome in AD 14. Caligula’s was named Gaius Caesar, after Julius Caesar, at birth. [Source: Wikipedia]

Caligula, or “Little Boot,” as he was called when he was young didn’t inherit his father’s leadership skills. Instead, after his father’s untimely death, Caligula spent much of his childhood in exile, only to return to Rome as the uneasy protégé of Tiberius, the paranoid emperor who had cast him and his family out. [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, April 2, 2024]

Germanicus, Caligula's father

Suetonius wrote: “His surname Caligula ["Little Boots"] he derived from a joke of the troops, because he was brought up in their midst in the dress of a common soldier. To what extent besides he won their love and devotion by being reared in fellowship with them is especially evident from the fact that when they threatened mutiny after the death of Augustus and were ready for any act of madness, the mere sight of Gaius unquestionably calmed them. For they did not become quiet until they saw that he was being spirited away because of the danger from their outbreak and taken for protection to the nearest town. Then at last they became contrite, and laying hold of the carriage and stopping it, begged to be spared the disgrace which was being put upon them. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“He attended his father also on his expedition to Syria. On his return from there he first lived with his mother and after her banishment, with his great-grandmother Livia; and when Livia died [29 A.D.], though he was not yet of age, he spoke her eulogy from the rostra. Then he fell to the care of his grandmother Antonia and in the nineteenth year of his age he was called to Capreae [the Isle of Capri] by Tiberius, on the same day assuming the gown of manhood and shaving his first beard, but without any such ceremony as had attended the coming of age of his brothers. Although at Capreae every kind of wile was resorted to by those who tried to lure him or force him to utter complaints, he never gave them any satisfaction, ignoring the ruin of his kindred as if nothing at all had happened, passing over his own ill-treatment with an incredible pretence of indifference, and so obsequious towards his grandfather and his household, that it was well said of him that no one had ever been a better slave or a worse master.

“Yet even at that time he could not control his natural cruelty and viciousness, but he was a most eager witness of the tortures and executions of those who suffered punishment, revelling at night in gluttony and adultery, disguised in a wig and a long robe, passionately devoted besides to the theatrical arts of dancing and singing, in which Tiberius very willingly indulged him,in the hope that through these his savage nature might be softened. This last was so clearly evident to the shrewd old man, that he used to say now and then that to allow Gaius to live would prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman people and a Phaethon for the world.”

Early Promise of Caligula

When Tiberius died in 37 A.D., 24-year-old Caligula became Rome’s emperor. At first Anthony A. Barrett, a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia, told National Geographic, the youthful emperor looked like he might follow in his respected father’s footsteps. “No one knew anything about him,” he says. “They probably thought they could control him.” Young, charming, and seemingly capable, Caligula began his reign reasonably.

Tiberius had made no provision for a successor. Hence the choice lay entirely with the senate, which selected a favorite of the army. This was Gaius Caesar, the son of the famous general, Germanicus. He was familiarly called by the soldiers “Caligula,” by which name he is generally known. He was joyfully welcomed by the people, and gave promise of a successful reign. He declared his intention of devoting himself to the public welfare. But the high hopes which he raised at his accession were soon dashed to the ground, when it was discovered that the empire was in the hands of a man who had lost his reason. The brief career of Caligula may be of interest as showing the vagaries of a diseased and unbalanced mind; but they have no special political importance, except as proving that the empire could survive even with a mad prince on the throne. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Suetonius wrote: “By thus gaining the throne he fulfilled the highest hopes of the Roman people, or I may say of all mankind, since he was the prince most earnestly desired by the great part of the provincials and soldiers, many of whom had known him in his infancy, as well as by the whole body of the city populace, because of the memory of his father Germanicus and pity for a family that was all but extinct. Accordingly, when he set out from Misenum, though he was in mourning garb and escorting the body of Tiberius, yet his progress was marked by altars, victims, and blazing torches, and he was met by a dense and joyful throng, who called him besides other propitious names their "star," their "chick," their "babe," and their "nursling." [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“When he entered the city, full and absolute power was at once put into his hands by the unanimous consent of the senate and of the mob, which forced its way into the Senate, and no attention was paid to the wish of Tiberius, who in his will had named his other grandson, still a boy, joint heir with Caligula. So great was the public rejoicing, that within the next three months, or less than that, more than a hundred and sixty thousand victims are said to have been slain in sacrifice.

“Gaius himself tried to rouse men's devotion by courting popularity in every way. After eulogizing Tiberius with many tears before the assembled people and giving him a magnificent funeral, he at once posted off to Pandateria and the Pontian islands, to remove the ashes of his mother and brother to Rome, and in stormy weather, too, to make his filial piety the more conspicuous. He approached them with reverence and placed them in the urns with his own hands. With no less theatrical effect he brought them to Ostia in a bireme with a banner set in the stern, and from there up the Tiber to Rome, where he had them carried to the Mausoleum [of Augustus] on two biers by the most distinguished men of the order of equites, in the middle of the day, when the streets were crowded. He appointed funeral sacrifices, too, to be offered each year with due ceremony, as well as games in the Circus in honor of his mother, providing a carriage to carry her image in the procession. But in memory of his father he gave to the month of September the name of Germanicus. After this, by a single decree of the senate, he heaped upon his grandmother Antonia whatever honors Livia Augusta had ever enjoyed; took his uncle Claudius, who up to that time had been a Roman eques,

Then Things Start to God Bad for Caligula

Between A.D. 39 and 40 Caligula's character changed. There were rumors that the emperor had health issues that affected his mental state; others spoke of a mind-altering potion given to him by his wife, Caesonia. Erin Blakemore wrote in National Geographic: About six months into his reign, the emperor’s demeanor changed. Some historians attribute the personality shift to a severe illness. But to Barrett, it’s simpler — the honeymoon was over, and the pressure was on. He believes that once the reality of the administrative and political burdens of being emperor became clear, the immature and unprepared leader struggled to live up to his title. Without training and lacking the political skills to keep the trust of both his subjects and the Senate, Caligula began to falter. [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, April 2, 2024]

Soon, Caligula was striking out at his enemies, demanding expensive and ill-advised military campaigns, and even ordering the death of his wife. Rumors circulated that the hedonistic emperor had sexual relationships with his own sisters, Julia Livilla and Agrippina the Younger (the future mother of Emperor Nero). Caligula eventually exiled them after discovering what seems to have been behind-the-scenes scheming against his reign. He courted controversy, goading and humiliating the Senate and ordering assassinations left and right.

Caligula's salacious deeds, like allowing his horse Incitatus at the banquet table, made him a target for gossip and public condemnation. In “Lives of the Caesars” Roman-era historian Suetonius said that besides a stall of marble, a manger of ivory, purple blankets and a collar of precious stones, Caligula even gave Incitatus a house, a troop of slaves and furniture ... and it is also said that he planned to make him consul. Caligula was so hated by his own men that they assassinated him in 41 A.D., but his notorious reputation isn't reflected in works of art depicting the Roman emperor, like this gilt bronze from the first century A.D.

Caligula’s Weird Behavior

Caligula was perhaps the world's first major league shell collector and in the process of doing this he supposedly declared war on the English Channel. When he arrived with his army at the English Channel he decided he would rather look for shells on the beach than conquer the islands on the other side of the channel. He used his entire army to collect shells and he returned to Rome with what he called "the spoils of a conquered ocean." The senate was directed to deposit these spoils among the treasures of the Capitol.

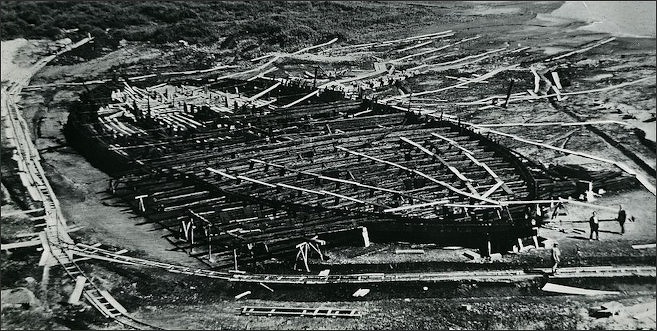

On Lake Nemi, south of Rome, Caligula built a floating palace, with five keels, 140 oak frames, two decks with on an onboard temple that included fluted columns, gilded roof tiles, terra-cotta roof ornaments, marble and ivory decorations and a sculptured terra-cotta frieze with blue, green and yellow paint. In order to exceed the luxuries of Lucullus —a rich politician from the late Roman Republican era — he spent the equivalent of several million dollars on a single meal. Numerous other stories of a similar kind are told.

Suetonius wrote: “In reckless extravagance he outdid the prodigals of all times in ingenuity, inventing a new sort of baths and unnatural varieties of food and feasts; for he would bathe in hot or cold perfumed oils, drink pearls of great price dissolved in vinegar, and set before his guests loaves and meats of gold, declaring that a man ought either to be frugal or Caesar. He even scattered large sums of money among the people from the roof of the Basilica Julia for several days in succession. He also built Liburnian galleys with ten banks of oars, with sterns set with gems, parti-colored sails, huge spacious baths, colonnades, and banquet-halls, and even a great variety of vines and fiuit trees; that on board of them he might recline at table from an early hour, and coast along the shores of Campania amid songs and choruses. He built villas and country houses with utter disregard of expense, caring for nothing so much as to do what men said was impossible. So he built moles out into the deep and stormy sea, tunnelled rocks of hardest flint, built up plains to the height of mountains and razed mountains to the level of the plain; all with incredible dispatch, since the penalty for delay was death. To make a long story short, vast sums of money, including the 2,700,000,000 sesterces which Tibelius Caesar had amassed, were squandered by him in less than the revolution of a year. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Caligula’s Outrageous Gladiator Shows

Suetonius wrote: “He gave several gladiatorial shows, some in the amphitheater of Taurus and some in the Saepta, in which he introduced pairs of African and Campanian boxers, the pick of both regions. He did not always preside at the games in person, but sometimes assigned the honor to the magistrates or to friends. He exhibited stage-plays continually, of various kinds and in many different places, sometimes even by night, lighting up the whole city. He also threw about gift-tokens of various kinds, and gave each man a basket of victuals. During the feasting he sent his share to a Roman eques opposite him, who was eating with evident relish and appetite, while to a senator for the same reason he gave a commission naming him praetor out of the regular order. He also gave many games in the Circus, lasting from early morning until evening, introducing between the races now a baiting of panthers and now the manoeuvres of the game called Troy; some, too, of special splendor, in which the Circus was strewn with red and green, while the charioteers were all men of senatorial rank. He also started some games off-hand, when a few people called for them from the neighboring balconies as he was inspecting the outfit of the Circus from the Gelotian house. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Besides this, he devised a novel and unheard of kind of pageant; for he bridged the gap between Baiae and the mole at Puteoli, a distance of about thirty-six hundred paces, by bringing together merchant ships from all sides and anchoring them in a double line, after which a mound of earth was heaped upon them and fashioned in the manner of the Appian Way. Over this bridge he rode back and forth for two successive days, the first day on a caparisoned horse, himself resplendent in a crown of oak leaves, a buckler, a sword, and a cloak of cloth of gold; on the second, in the dress of a charioteer in a car drawn by a pair of famous horses, carrying before him a boy named Dareus, one of the hostages from Parthia, and attended by the entire praetorian guard and a company of his friends in Gallic chariots. I know that many have supposed that Gaius devised this kind of bridge in rivalry of Xerxes, who excited no little admiration by bridging the much narrower Hellespont; others, that it was to inspire fear in Germany and Britain, on which he had designs, by the fame of some stupendous work. But when I was a boy, I used to hear my grandfather say that the reason for the work, as revealed by the emperor's confidential courtiers, was that Thrasyllus the astrologer had declared to Tiberius, when he was worried about his suceessor and inclined towards his natural grandson, that Gaius had no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding about over the gulf of Baiae with horses.

“He also gave shows in foreign lands, Athenian games at Syracuse in Sicily, and miscellaneous games at Lugdunum in Gallia; at the latter place also a contest in Greek and Latin oratory, in which, they say, the losers gave prizes to the victors and were forced to compose eulogies upon them, while those who were least successful were ordered to erase their writings with a sponge or with their tongue unless they elected rather to be beaten with rods or thrown into the neighboring river.

“He completed the public works which had been half finished under Tiberius, namely the temple of Augustus and the theater of Pompeius. He likewise began an aqueduct in the region near Tibur and an amphitheater beside the Saepta, the former finished by his successor Claudius, while the latter was abandoned. At Syracuse he repaired the city walls, which had fallen into ruin through lapse of time, and the temples of the gods. He had planned, besides, to rebuild the palace of Polycrates at Samos, to finish the temple of Didymaean Apollo at Ephesus, to found a city high up in the Alps, but, above all, to dig a canal through the Isthmus in Greece, and he had already sent a chief centurion to survey the work.

Was Caligula's Insane?

Caligula is believed to have suffered from epilepsy as a child and later had a brain fever that made him mentally ill. He was widely regarded as insane when he was Emperor. He believed himself a god and wasted huge sums of money on senseless projects. To lead his army over the sea he constructed a five-kilometer-long bridge over the Gulf of Baiae, a part of the Bay of Naples, and conducted his soldiers over it in a triumphal procession. According to Suetonius he invited a crowd to the dedication of then bridge and then had them all pushed in the water so he could watch them drown. In spite of his extreme cruelty, Caligula was a greater lover of animals. He named his beloved horse to be consul which some have said is a like a U.S. President naming his pet to the Supreme Court." [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Erin Blakemore wrote in National Geographic:This capricious behavior — and accusations he did things like pit physically incapable gladiators against wild beasts for sport — has long fueled speculation that Caligula suffered from some kind of mood disorder or mental illness. Retroactive diagnoses blame everything from epileptic psychosis to encephalitis. [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, April 2, 2024]

But Barrett thinks Caligula was sane — a fact that sheds an even more sinister light on his casual brutality. “Right up until the end, Caligula made rational decisions,” says Barrett, comparing him more to a Joseph Stalin as opposed to a deranged Hitler figure. “He could distinguish reality from fantasy.” But the monarch’s reality was one suffused in total power — a privilege he wielded strategically and at will.

That power would have gone to anyone’s head. “When he entered the city, full and absolute power was at once put into his hands by the unanimous consent of the senate and the mob,” claimed Suetonius, a historian known for his biographies of the Caesars. From the first, though, Caligula’s imperial might was bathed in blood of thousands of animal sacrifices. “So great was the public rejoicing,” said Suetonius, “that within the next three months…more than a hundred and sixty thousand victims are said to have been slain in sacrifice.”

Caligula's Self-Deification

Caligula claimed he was a god while alive. He said he communed with Jupiter (the king of the Roman gods) and bragged about having sex with the moon. He built a bridge from the Palatine hill, where he resided, to the Capitoline, that he might be “next door neighbor to Jupiter” and he threatened to set up his own image in the temple at Jerusalem and to compel the Jews to worship it.

Suetonius wrote: “Chancing to overhear some kings, who had come to Rome to pay their respects to him, disputing at dinner about the nobility of their descent, he cried: "Let there be one Lord, one King." And he came near assuming a crown at once and changing the semblance of a principate into the form of a monarchy. But on being reminded that he had risen above the elevation both of princes and kings, he began from that time on to lay claim to divine majesty; for after giving orders that such statues of the gods as were especially famous for their sanctity or their artistic merit, including that of Jupiter of Olympia, should be brought from Greece, in order to remove their heads and put his own in their place, he built out a part of the Palace as far as the Forum, and making the temple of Castor and Pollux its vestibule, he often took his place between the divine brethren, and exhibited himself there to be worshipped by those who presented themselves; and some hailed him as Jupiter Latiaris. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“He also set up a special temple to his own godhead, with priests and with victims of the choicest kind. In this temple was a life-sized statue of the emperor in gold, which was dressed each day in clothing such as he wore himself, The richest citizens used all their influence to secure the priesthoods of his cult and bid high for the honor. The victims were flamingoes, peacocks, black grouse, guinea-hens a and pheasants, offered day by day each after its own kind. At night he used constantly to invite the full and radiant moon to his embraces and his bed, while in the daytime he would talk confidentially with Jupiter Capitolinus, now whispering and then in turn putting his ear to the mouth of the god, now in louder and even angry language; for he was heard to make the threat: "Lift me up, or I'll lift you." But finally won by entreaties, as he reported, and even invited to live with the god, he built a bridge over the temple of the Deified Augustus, and thus joined his Palace to the Capitol. Presently, to be nearer yet, he laid the foundations of a new house in the court of the Capitol.

Caligula's Sadism and Cruelty

Caligula brutally murdered people for fun, used the law as an instrument of torture and once lamented that the Rome didn’t have “a single neck” for him to sever. Patrick Ryan wrote in Listverse: “. He believed prisoners should feel a painful death. He would kill his opponents slowly and painfully over hours or days. He decapitated and strangled children. People were beaten with heavy chains. He forced families to attend their children’s execution. Many people had their tongues cut off. He fed prisoners to a lions, panthers and bears and often killed gladiators. One gladiator alone was beaten up for two days full days. He sometimes ordered people to be killed by elephants. He caused many to die of starvation. Sawing people was one of his favorite things to do, which filleted the spine and spinal cord from crotch down to the chest. He liked to chew up the testicles of victims. One time Caligula said “I wish Rome had but one neck, so that I could cut off all their heads with one blow!”“ [Source: Patrick Ryan, Listverse, May 30, 2012]

Suetonius wrote: “ Being disturbed by the noise made by those who came in the middle of the night to secure the free seats in the Circus, he drove them all out with cudgels; in the confusion more than twenty Roman equites were crushed to death, with as many matrons and a countless number of others. At the plays in the theater, sowing discord between the people and the equites, he scattered the gift tickets ahead of time, to induce the rabble to take the seats reserved for the equestrian order. At a gladiatorial show he would sometimes draw back the awnings when the sun was hottest and give orders that no one be allowed to leave; then removing the usual equipment, he would match worthless and decrepit gladiators against mangy wild beasts, and have sham fights between householders who were of good repute, but conspicuous for some bodily infirmity. Sometimes too he would shut up the granaries and condemn the people to hunger...An ex-praetor who had retired to Anticyra for his health, sent frequent requests for an extension of his leave, but Caligula had him put to death, adding that a man who had not been helped by so long a course of hellebore needed to be bled. On signing the list of prisoners who were to be put to death later, he said that he was clearing his accounts. Having condemned several Gauls and Greeks to death in a body, he boasted that he had subdued Gallograecia. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“The following are special instances of his innate brutality. When cattle to feed the wild beasts which he had provided for a gladiatorial show were rather costly, he selected criminals to be devoured, and reviewing the line of prisoners without examining the charges, but merely taking his place in the middle of a colonnade, he bade them be led away "from baldhead to baldhead." A man who had made a vow to fight in the arena if the emperor recovered, he compelled to keep his word, watched him as he fought sword in hand, and would not let him go until he was victorious, and then only after many entreaties. Another who had offered his life for the same reason, but delayed to kill himself, he turned over to his slaves, with orders to drive him through the streets decked with sacred boughs and fillets, calling for the fulfilment of his vow, and finally hurl him from the embankment.

“Many men of honorable rank were first disfigured with the marks of branding-irons and then condemned to the mines, to work at building roads, or to be thrown to the wild beasts; or else he shut them up in cages on all fours, like animals, or had them sawn asunder. Not all these punishments were for serious offences, but merely for criticizing one of his shows, or for never having sworn by his Genius. He forced parents to attend the executions of their sons, sending a litter for one man who pleaded ill health, and inviting another to dinner immediately after witnessing the death, and trying to rouse him to gaiety and jesting by a great show of affability. He had the manager of his gladiatorial shows and beast-baitings beaten with chains in his presence for several successive days, and would not kill him until he was disgusted at the stench of his putrefied brain. He burned a writer of Atellan farces alive in the middle of the arena of the amphitheatre, because of a humorous line of double meaning. When a Roman eques on being thrown to the wild beasts loudly protested his innocence, he took him out, cut off his tongue, and put him back again.

“Having asked a man who had been recalled from an exile of long standing, how in the world he spent his time there, the man replied by way of flattery: "I constantly prayed the gods for what has come to pass, that Tiberius might die and you become emperor." Thereupon Caligula, thinking that his exiles were likewise praying for his death, sent emissaries from island to island to butcher them all. Wishing to have one of the senators torn to pieces, he induced some of the members to assail him suddenly, on his entrance into the Senate, with the charge of being a public enemy, to stab him with their styluses, and turn him over to the rest to be mangled; and his cruelty was not sated until he saw the man's limbs, members, and bowels dragged through the streets and heaped up before him.

“He seldom had anyone put to death except by numerous slight wounds, his constant order, which soon became well-known, being: "Strike so that he may feel that he is dying." When a different man than he had intended had been killed, through a mistake in the names, he said that the victim too had deserved the same fate. He often uttered the familiar line of the tragic poet [Accius, Trag., 203]: — "Let them hate me, so they but fear me." He often inveighed against all the senators alike, as adherents of Seianus and informers against his mother and brothers, producing the documents which he pretended to have burned, and upholding the cruelty of Tiberius as forced upon him, since he could not but believe so many accusers. He constantly tongue-lashed the equestrian order as devotees of the stage and the arena. Angered at the rabble for applauding a faction which he opposed, he cried: "I wish the Roman people had but a single neck," and when the brigand Tetrinius was demanded, he said that those who asked for him were Tetriniuses also. Once a band of five retiarii in tunics, matched against the same number of secutores, yielded without a struggle; but when their death was ordered, one of them caught up his trident and slew all the victors. Caligula bewailed this in a public proclamation as a most cruel murder, and expressed his horror of those who had had the heart to witness it

“As a sample of his humor, he took his place beside a statue of Jupiter, and asked the tragic actor Apelles which of the two seemed to him the greater, and when he hesitated, Caligula had him flayed with whips, extolling his voice from time to time, when the wretch begged for mercy, as passing sweet even in his groans. Whenever he kissed the neck of his wife or sweetheart, he would say: "Off comes this beautiful head whenever I give the word." He even used to threaten now and then that he would resort to torture if necessary, to find out from his dear Caesonia why he loved her so passionately.”

Caligula's Treatment of His Family

Suetonius wrote: “He did not wish to be thought the grandson of Agrippa, or called so, because of the latter's humble origin; and he grew very angry if anyone in a speech or a song included Agrippa among the ancestors of the Caesars. He even boasted that his own mother was born in incest, which Augustus had committed with his daughter Julia.He often called his great-grandmother Livia Augusta "a Ulysses in petticoats," and he had the audacity to accuse her of low birth in a letter to the senate, alleging that her maternal grandfather had been nothing but a decurion of Fundi; whereas it is proved by public records that Aufidius Lurco held high offices at Rome. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“When his grandmother Antonia asked for a private interview, he refused it except in the presence of the praefect Macro, and by such indignities and annoyances he caused her death; although some think that he also gave her poison. After she was dead, he paid her no honor, but viewed her burning pyre from his dining-room. He had his brother Tiberius put to death without warning, suddenly sending a tribune of the soldiers to do the deed; besides driving his father-in-law Silanus to end his life by cutting his throat with a razor. His charge against the latter was that Silanus had not followed him when he put to sea in stormy weather, but had remained behind in the hope of taking possession of the city in case he should be lost in the storm; against Tiberius, that his breath smelled of an antidote, which he had taken to guard against being poisoned at his hand. Now as a matter of fact, Silanus was subject to sea-sickness and wished to avoid the discomforts of the voyage, while Tiberius had taken medicine for a chronic cough, which was growing worse. As for his uncle Claudius, he spared him merely as a laughingstock.

“It would be trivial and pointless to add to this an account of his treatment of his relatives and friends, Ptolemy, son of king Juba, his cousin (for he was the grandson of Marcus Antonius by Antonius' daughter Selene), and in particular Macro himself and even Ennia, who helped him to the throne; all these were rewarded for their kinship and their faithful services by a bloody death. He was no whit more respectful or mild towards the senate, allowing some who had held the highest offices to run in their togas for several miles beside his chariot and to wait on him at table, standing napkin in hand a either at the head of his couch, or at his feet. Others he secretly put to death, yet continued to send for them as if they were alive, after a few days falsely asserting that they had committed suicide. When the consuls forgot to make proclamation of his birthday, he deposed them, and left the state for three days without its highest magistrates. He flogged his quaestor, who was charged with conspiracy, stripping off the man's clothes and spreading them under the soldiers' feet, to give them a firm footing as they beat him. He treated the other orders with like insolence and cruelty....When he was on the point of killing his brother, and suspected that he had taken drugs as a precaution against poison, he cried: "What! an antidote against Caesar?" After banishing his sisters, he made the threat that he not only had islands, but swords as well.”

Caligula's Sex Life

Caligula coin (tails three sisters) Caligula had four wives and demanded sex with many women including his three sisters. He raped one of his sisters and forced her to marry his male lover, Marcus Lapidus. He made prostitutes out of his other sisters and made love to his friend's wives. After having sex with someone's wife he prohibited them from every having intercourse with their husbands again :then publicly issued divorce proceedings in their husband's name. Among the sweet nothings he whispered into the ears of his lovers was "Off comes this head whenever I give the word." According to Pliny, Lollia Pualina, the consort of Caligula, was “covered with emeralds and pearl interlaced and alternately shining all over her head, hair, ears, neck and fingers, the sum total amounting to 40,000,000 sesterces." The annual salary of a soldier was around, 1,200 sesterces.

Suetonius wrote: “ “It is not easy to decide whether he acted more basely in contracting his marriages, in annulling them, or as a husband. At the marriage of Livia Orestilla to Gaius Piso, he attended the ceremony himself, gave orders that the bride be taken to his own house, and within a few days divorced her; two years later he banished her, because of a suspicion that in the meantime she had gone back to her former husband. Others write that being invited to the wedding banquet, he sent word to Piso, who reclined opposite to him: "Don't take liberties with my wife," and at once carried her off with him from the table, the next day issuing a proclamation that he had got himself a wife in the manner of Romulus and Augustus. When the statement was made that the grandmother of Lollia Paulina, who was married to Gaius Memmius, an ex-consul commanding armies, had once been a remarkably beautiful woman, he suddenly called Lollia from the province, separated her from her husband, and married her, then in a short time he put her away, with the command never to have intercourse with anyone. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“Though Caesonia was neither beautiful nor young, and was already mother of three daughters by another, besides being a woman of reckless extravagance and wantonness, he loved her not only more passionately but more faithfully, often exhibiting her to the soldiers riding by his side, decked with cloak, helmet and shield, and to his friends even in a state of nudity. He did not honor her with the title of wife until she had borne him a child, announcing on the selfsame day that he had married her and that he was the father of her babe. This babe, whom he named Julia Drusilla, he carried to the temples of all the goddesses, finally placing her in the lap of Minerva and commending to her the child's nurture and training. And no evidence convinced him so positively that she was sprung from his own loins as her savage temper, which was even then so violent that she would try to scratch the faces and eyes of the little children who played with her.

“He respected neither his own chastity nor that of anyone else. He is said to have had unnatural relations with Marcus Lepidus, the pantomimic actor Mnester, and certain hostages. Valerius Catullus, a young man of a consular family, publicly proclaimed that he had violated the emperor and worn himself out in commerce with him. To say nothing of his incest with his sisters and his notorious passion for the concubine Pyrallis, there was scarcely any woman of rank whom he did not approach.

“These as a rule he invited to dinner with their husbands, and as they passed by the foot of his couch, he would inspect them critically and deliberately, as if buying slaves, even putting out his hand and lifting up the face of anyone who looked down in modesty; then as often as the fancy took him he would leave the room, sending for the one who pleased him best, and returning soon afterward with evident signs of what had occurred, he would openly commend or criticize his partner, recounting her charms or defects and commenting on her conduct. To some he personally sent a bill of divorce in the name of their absent husbands, and had it entered in the public records.

“He added to the enormity of his crimes by the brutality of his language. He used to say that there was nothing in his own character which he admired and approved more highly than what he called his "lasting power", that is, his shameless impudence [a sexual innuendo]. When his grandmother Antonia gave him some advice, he was not satisfied merely not to listen but replied: "Remember that I have the right to do anything to anybody."

Caligula's Sex Life with His Sisters

Suetonius wrote: “He lived in habitual incest with all his sisters, and at a large banquet he placed each of them in turn below him, while his wife reclined above. Of these he is believed to have violated Drusilla when he was still a minor, and even to have been caught lying with her by his grandmother Antonia, at whose house they were brought up in company. Afterwards, when she was the wife of Lucius Cassius Longinus, an ex-consul, he took her from him and openly treated her as his lawful wife; and when ill, he made her heir to his property and the throne. When she died, he appointed a season of public mourning, during which it was a capital offence to laugh, bathe, or dine in company with one's parents, wife, or children. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“He was so beside himself with grief that suddenly fleeing the city by night and traversing Campania, he went to Syracuse and hurriedly returned from there without cutting his hair or shaving his beard. And he never afterwards took oath about matters of the highest moment, even before the assembly of the people or in the presence of the soldiers, except by the godhead of Drusilla. The rest of his sisters he did not love with so great affection, nor honor so highly, but often prostituted them to his favorites; so that he was the readier at the trial of Aemilius Lepidus to condemn them, as adulteresses and privy to the conspiracies against him; and he not only made public letters in the handwriting of all of them, procured by fraud and seduction, but also dedicated to Mars the Avenger, with an explanatory inscription, three swords designed to take his life.”

Huge Taxes to Pay Off Caligula's Debts

José Antonio Rodríguez Valcárcel wrote in National Geographic History: Caligula spent extravagently during his reign, on both projects and frivolous projects. He had no qualms about resorting to all manner of trickery and extortion to get the money that funded his excessive expenditures. High taxes were set, inheritances confiscated, and prominent wealthy citizens found themselves subject to legal action. Nobody’s possessions were safe and many lived in fear of becoming the next target of Caligula’s caprice. [Source José Antonio Rodríguez Valcárcel, National Geographic History, February 26, 2020]

Suetonius wrote: “Having thus impoverished himself, from very need he turned his attention to pillage through a complicated and cunningly devised system of false accusations, auction sales, and imposts. He ruled that Roman citizenship could not lawfully be enjoyed by those whose forefathers had obtained it for themselves and their descendants, except in the case of sons, since "descenda “When he had roused such fear in this way that he came to be named openly as heir by strangers among their intimates and by parents among their children, he accused them of making game of him by continuing to live after such a declaration, and to many of them he sent poisoned dainties. He used further to conduct the trial of such cases in person, naming in advance the sum which he proposed to raise at each sitting, and not rising until it was made up. Impatient of the slightest delay, he once condemned in a single sentence more than forty who were accused on different counts, boasting to Caesonia, when she woke after a nap, of the great amount of business he had done while she was taking her afternoon sleep. Appointing an auction, he put up and sold what was left from all the shows, personally soliciting bids and running them up so high, that some who were forced to buy articles at an enormous price and were thus stripped of their possessions, opened their veins. A well-known incident is that of Aponius Saturninus; he fell asleep on one of the benches, and as the auctioneer was warned by Gaius not to overlook the praetorian gentleman who kept nodding to him, the bidding was not stopped until thirteen gladiators were knocked down to the unconscious sleeper at nine million sesterces.

“When he was in Gaul and had sold at immense figures the jewels, furniture, slaves, and even the freedmen of his sisters who had been condemned to death, finding the business so profitable, he sent to the city for all the paraphernalia of the old palace, seizing for its transportation even public carriages and animals from the bakeries; with the result that bread was often scarce at Rome and many who had cases in court lost them from inability to appear and meet their bail. To get rid of this furniture, he resorted to every kind of trickery and wheedling, now railing at the bidders for avarice and because they were not ashamed to be richer than he, and now feigning regret for allowing common men to acquire the property of princes. Having learned that a rich provincial had paid those who issued the emperor's invitations two hundred thousand sesterces, to be smuggled in among the guests at one of his dinner-parties, he was not in the least displeased that the honor of dining with him was rated so high; but when next day the man appeared at his auction, he sent a messenger to hand him some trifle or other at the price of two hundred thousand sesterces and say that he should dine with Caesar on his personal invitation.

“He levied new and unheard of taxes, at first through the publicans and then, because their profit was so great, through the centurions and tribunes of the praetorian guard; and there was no class of commodities or men on which he did not impose some form of tariff. On all eatables sold in any part of the city he levied a fixed and definite charge; on lawsuits and legal processes begun anywhere, a fortieth part of the sum involved, providing a penalty in case anyone was found guilty of compromising or abandoning a suit; on the daily wages of porters, an eighth; on the earnings of prostitutes, as much as each received for one embrace; and a clause was added to this chapter of the law, providing that those who had ever been prostitutes or acted as panders should be liable to this public tax, and that even matrimony should not be exempt.

Roman Empire Under Caligula, Red: Italy and Roman provinces Blue: Independent countries Yellow: Client states (Roman puppets) Light Purple: Mauretania seized by Caligula Dark purple: Former Roman provinces Thrace and Commagena made client states by Caligula

“When taxes of this kind had been proclaimed, but not published in writing, inasmuch as many offences were committed through ignorance of the letter of the law, he at last, on the urgent demand of the people, had the law posted up, but in a very narrow place and in excessively small letters, to prevent the making of a copy. To leave no kind of plunder untried, he opened a brothel in his palace, setting apart a number of rooms and furnishing them to suit the grandeur of the place, where matrons and freeborn youths should stand exposed. Then he sent his pages about the fora and basilicas, to invite young men and old to enjoy themselves, lending money on interest to those who came and having clerks openly take down their names, as contributors to Caesar's revenues. He did not even disdain to make money from play, and to increase his gains by falsehood and even by perjury. Having on one occasion given up his place to the player next him and gone into the courtyard, he spied two wealthy Roman knights passing by; he ordered them to be seized at once and their property confiscated and came back exultant, boasting that he had never played in better luck.

“But when his daughter was born, complaining of his narrow means, and no longer merely of the burdens of a ruler but of those of a father as well, he took up contributions for the girl's maintenance and dowry. He also made proclamation that he would receive New Year's gifts, and on the Kalends of January took his place in the entrance to the Palace, to clutch the coins which a throng of people of all classes showered on him by handfuls and lapfuls. Finally, seized with a mania for feeling the touch of money, he would often pour out huge piles of gold pieces in some open place, walk over them barefooted, and wallow in them for a long time with his whole body.

Caligula’s Enemies and Plots to Kill Him

José Antonio Rodríguez Valcárcel wrote in National Geographic History: According to his biographer Suetonius, Caligula believed himself to be a god and often said: “Remember that I have the right to do anything to anybody.” He humiliated senators by making them run behind his litter or forcing them to fight for his amusement. Suetonius wrote, "When the consuls forgot to make proclamation of his birthday, he deposed them, and left the state for three days without its highest magistrates." [Source José Antonio Rodríguez Valcárcel, National Geographic History, February 26, 2020]

Numerous plots, real or alleged, were hatched, like the one led by Lentulus Gaetulicus in Germania in A.D. 39, and another devised by close followers of Callistus, one of the richest men in Rome. Many yearned to take revenge on the emperor for past affronts but almost everyone remained afraid of falling out of his favor. The Roman historian Tacitus summed up the situation perfectly in his dramatic expression ocultae Gaium insidiae, “hidden malice toward Gaius.” Secret hatred seethed beneath a frightened mask of adulation. (Citizenship was the path to power in ancient Rome.)

Historian Cassius Dio wrote that practically everyone at Caligula’s court wanted him dead. Even those who were not actively conspiring to kill him kept quiet and allowed plots to proceed in the hope of ending the nerve-wracking uncertainty of their possessions and lives being utterly at the mercy of a tyrannical and capricious emperor.

In The Antiquities of the Jews, the first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus records that Caligula faced hostility from all sides. He said that there were three groups of conspirators simultaneously involved in the plot that ended Caligula's life. One was headed by Emilius Regulus, about whom little is known. Annius Vinicianus led another group and was apparently somehow connected with a thwarted coup in A.D. 39.

It’s almost certain that there were many more plots than those mentioned in the written accounts. Possible widespread involvement of Caligula’s court would explain why he never learned of the threat. Yet, despite support and ample opportunities, the plotters hesitated when it came to actually carrying out the deed.

Murder of Caligula

In A.D. 41, Caligula was killed in a plot hatched by Casius Chaerea, a man whom Caligula had publicly humiliated, mocked at court for his effeminacy and subjected to cruel practical jokes. José Antonio Rodríguez Valcárcel wrote in National Geographic History: Cassius Chaerea was a member of the Praetorian Guard (the troops closest to the emperor). Chaerea wanted revenge but turned to others for support, including a fellow tribune and one of his superiors, a prefect of the Praetorian Guard. Concealing his personal hatred, he tried to convince them to join him in denouncing Caligula as the oppressor of Rome and the empire. He failed to secure explicit support. However, he revealed his plans to a trusted colleague, another tribune, Cornelius Sabinus, and the pair became the principal players in the plot to end the emperor’s life. [Source José Antonio Rodríguez Valcárcel, National Geographic History, February 26, 2020]

Having exhausted all other options, they finally decided to strike the fatal blow during the Palatine Games. These were a series of events held each January to honor Augustus, the first emperor of Rome who ruled from 27 B.C. to A.D.14. Initially the attack was planned for the first day of the games, but complications and indecision pushed the date to the games’ final day. They dared not delay any longer—people were by now openly talking about the plot, and the emperor was about to set off for the relative safety of Alexandria in Egypt. Meanwhile the auguries were warning Caligula of impending doom: The oracle at Fortuna’s temple in Antium warned him to protect himself against Chaerea; the mathematician and astrologer Sulla had predicted that the emperor would die a violent death.

As the sun rose on the final day of the games, Chaerea met with his co-conspirators, then went to the palace in the early hours of the morning. Meanwhile, on Palatine Hill, crowds began to jostle along the Sacred Road, ancient Rome’s main street. In the half-light of dawn they gathered around the theater built for the games where Caligula was due to attend a performance. On this special day the best seats were not reserved, and when the venue opened, the mob of men and women, citizens and slaves, rushed inside, shouting and cheering.

When Caligula finally arrived at the theater, he opened the day’s festivities by making a sacrifice to Augustus. Indeed Caligula appeared to be in a fine mood: He was talkative, courteous, and friendly. He took his seat in the right-hand side of the theater, surrounded by his close family and friends. The watchful Chaerea sat near Caligula, having made sure that his co-conspirators were in position inside and outside the building.

The day’s performance was Laureolus, a popular mimed play by Catullus. It told the story of a gang of bandits whose leader, Laureolus, was adept at escaping from dire situations until one day he was caught and crucified. It was to be followed by the tragedy Cinyras. Both were to be performed by the great actor Mnester. A nighttime show was also planned, in which Egyptians and Ethiopians would perform scenes depicting the underworld—as imagined by Romans, with the entertainment rounded off by war dances and sacred songs about religious mysteries.

Extending into the next day, the plays had not finished. Sometime after midday Caligula decided to have a bath and lunch, intending to return to the festivities later. He had made similar arrangements on previous days. By then some plotters had grown impatient, but they were stirred by the public’s sudden cries that announced that caesar was on the move. His procession left the theater led by notables such as Claudius and Valerius Asiaticus, but then Caligula made a fateful decision. He deviated from his usual well-guarded route, along which the procession had already started, and instead took a shortcut through a dark, narrow, lonely passageway. Suetonius called it a “crypt” and it may have run between the houses of Tiberius and Nero.

It was there that Chaerea found Caligula. The soldier raised his sword and slashed him between the collarbone and neck. Caligula tried to run away but Sabinus was lying in wait and knocked him to the ground with another sword stroke. According to Suetonius, after Cassius Chaerea and Cornelius Sabinus struck Caligula, the plotters stabbed him thirty times, continuing to attack after he was dead. "Hoc age! Accipe ratum! Repete!" went the cry. “Take that! So be it! And again!” Cassius Dio claims they even “tasted his esh.” Caligula’s wife and daughter were also murdered to prevent any possibility of a legitimate successor.

After the assassination, the Senate met in the capitol. Led by the two consuls, Saturninus and Secundus, they had to decide on the future of Rome and its empire. They could select a new emperor from among its leading senators; many others wanted to restore the republic as before Augustus. Alternatively they might return to the even older system of monarchy. But their lofty deliberations were cut short as the army outmaneuvered them. Claudius, the assassinated emperor’s uncle, was discovered hiding by a unit of Praetorian Guardsmen. They preferred imperial rule, a system that had greatly benefited them, so they took the frightened senator back to their camp to proclaim him emperor. For the following days the future of Rome hung in the balance, but few mourned the murder of Caligula.

Excavation of Caligula's Lake Nevi boat

Lanta Davis and Vince Reighard wrote in National Geographic:According to ancient historian Cassius Dio, in his final moments, Caligula learned: “He had but one neck,” while Rome had “many hands”—a reference to the collective power of the people and his assassins. Stabbed repeatedly, his killers allegedly mutilated his corpse, thrusting “their swords through his privates,” while one sensationalist account said they “tasted of his flesh.” After his murder, his remains were hastily cremated on a makeshift pyre and thrown into a shallow grave. It wasn’t long before his spirit reportedly began to haunt the Palatine Hill, where his murder took place. Night after night, eerie specters plagued the gardens where he was laid to rest, with no evening passing without some “fearsome apparition.” Before his assassination, Caligula had exiled his sister Agrippina to the Pontiane Islands, where he sent her ominous letters reminding her that he not only possessed islands for his enemies but “swords as well.” Despite this, Agrippina returned to Rome to give her brother a proper burial—perhaps a political maneuver, but also an attempt to quiet his malevolent spirit due to the improper burial. [Source Lanta Davis and Vince Reighard, National Geographic, October 4, 2024]

Was Caligula Really as Bad as They Say

Erin Blakemore wrote in National Geographic:, Murder? Check. Incest? Maybe. The brutal exercise of political power? Definitely. In the annals of infamous emperors, few come close to But was Caligula really that bad? “He was a terrible emperor,” says Barrett, But he wasn’t that bad if we’re using bad in the sense of extravagant, ridiculous behavior.” Despite those excesses, says Barrett, it’s important to question the accounts of Caligula’s contemporaries. Their work was informed by his political enemies and distorted by hearsay. The most trustworthy chronicler of his day, Tacitus, did write about Caligula, but unfortunately his work has been lost. The histories that remained contain “ridiculous and absurd” accounts of the emperor, says Barrett, who compares Suetonius and his contemporary, Cassius Dio, to tabloid reporters in search of a scoop on the embattled emperor. [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, April 2, 2024]

Caligula’s behavior was definitely cruel but likely a little less juicy than Dio and Suetonius would have you believe. Take Caligula’s widely reported demands to be treated like a god. That would have been standard practice in Roman colonies, which were forced to recognize the so-called “imperial cult” of Rome. But Barrett says there is no evidence like coinage that would support a similar demand within Rome or even Italy. Then there’s the infamous tale of making his horse a consul — a threat that never came to fruition. Barrett attributes that episode to an annoyed emperor mocking his enemies in the senate — enemies he considered so incompetent and feckless, they could easily be replaced by an animal.

But even if Caligula never engaged in the most outrageous exploits attributed to him, the fact of his outsized and extremely long-lasting reputation remains. What accounts for the ongoing notoriety of a man whose rule lasted less than four years nearly two millennia ago? “Humans love villains,” says Barrett, and Caligula enjoys ongoing fame thanks to a combination of personal charisma and stubborn enmity among his contemporaries. There’s another factor, says Barrett: The passage of time. Because so many years have passed since his exploits, Barrett says, “Caligula belongs to a world that is so alien to us now that we can enjoy his villainy with a clear conscience.”

We have only one source who lived at the same time as Caligula and met him. Philo of Alexandria visited Caligula to petition the emperor for Jewish rights and wrote briefly about the experience in "On the Embassy to Gaius." Philo described Caligula as sane but hostile and self-absorbed. [Source J. Wisniewski, Listverse, July 21, 2014]

Caligula Seen in a Different Light

In a discussion of Aloys Winterling, biography, “Caligula”, Adam Kirsch wrote in The New Yorker: Winterling “seeks to rehabilitate one of the most infamous Roman emperors, commonly believed to have been deranged. He begins with a recitation of the charges that historians have levelled against Caligula, who reigned from 37 to 41 A.D.: “He drank pearls dissolved in vinegar and ate food covered with gold leaf. He forced men and women of high rank to have sex with him, turned part of his palace into a brothel, and even committed incest with his own sisters. . . . He considered himself superhuman and forced contemporaries to worship him as a god.” Yet the title of Winterling’s introduction is “A Mad Emperor?,” and it becomes clear that his answer to the question is no. [Source: Adam Kirsch, The New Yorker, January 2, 2012 ]

“All the sources—especially Suetonius, whose “Twelve Caesars” is the basis for this catalogue of horrors—may portray Caligula as a raving madman, but Winterling puts this treatment in the context of classical history writing, which had a habit of charging those who had fallen from power with outrageous villainies. “The accounts of Caligula surviving from antiquity pursue the clearly recognizable goal of depicting the emperor as an irrational monster,” he writes. “They provide demonstrably false information to support this picture of him and omit information that could contradict it.” To understand what Caligula was really up to, Winterling insists, we must understand the political culture of the early Roman Empire. When Augustus Caesar established the Empire, he was widely beloved for putting an end to generations of devastating civil wars. At the same time, however, Rome’s senatorial aristocracy could not easily let go of the Republican traditions that gave them a privileged place in the state. Augustus finessed this situation by wielding power quietly: he lived on a modest scale, treated other senators as peers, and allowed the façade of the Republic to cover the reality of autocracy.

“But Caligula, who, at the age of twenty-four, became the third Roman emperor, was unable to maintain this delicate balance. What embittered Caligula, Winterling argues, and has ruined his historical reputation, was the enmity of the senators, who chafed against his rule and plotted to end it. Instead of meeting this opposition with suavity, as Augustus had, Caligula turned a withering, bitter sarcasm on Rome’s aristocracy, and was intent on humiliating them and reminding them of their servitude. “His aim,” Winterling writes, “was to destroy the aristocratic hierarchy as such and expose it to ridicule.” Seen in this light, some of Caligula’s pranks become more understandable. Notoriously, for instance, he wanted to make his favorite horse, Incitatus, a consul—on the face of it, an insane thing to do. But Winterling suggests that this was never a serious plan, merely a way to mock the aristocrats, for whom the consulship was the crown of a career in politics: “To equip the emperor’s horse with a sumptuous household and destine it for the consulship satirized the main aim of aristocrats’ lives and laid it open to ridicule.”

“Caligula’s madness, in other words, was a deliberate exercise in political showmanship. This principle allows Winterling to explain another baffling episode in Caligula’s biography, when he supposedly declared war on the English Channel. According to Suetonius, the emperor was in Gaul planning a campaign in Germany when he changed his mind and marched his legions to the French coast, facing Britain. He set up his artillery facing the ocean, and “no one knew or could imagine what he was going to do.” Then he abruptly ordered the troops to collect seashells as booty from their “victory” over the waves, and gave them the bonus payment customary after triumphs. For Winterling, this story sounds insane only because it was distorted by the historian. What probably happened, he writes, is that Caligula was planning a genuine invasion of Britain, when his troops—fearful of going to a place that at that time was terra incognita, outside the bounds of the civilized world—mutinied and refused to go any farther. In this scenario, Caligula’s order to collect shells was another form of elaborate sarcasm, a way of humiliating the soldiers “who had assembled at the edge of the sea but refused to fight.”

“Winterling grants that “there is no knowing what actually happened in any detail,” but he prefers this explanation to the one Suetonius offers, which is that Caligula was simply psychotic. After all, “if Caligula was mad,” Winterling asks, “why wasn’t he removed from public view, and placed under the care of a physician—just as was done when rulers in later European history became mentally ill?” It sounds like a reasonable enough argument—until you remember, for instance, that Hitler’s orders were followed until the very end, even when they were plainly mad and cost millions of lives, including those of his own soldiers. From Stalin to Mao to Idi Amin, the twentieth century surely gave plenty of proof that psychotic leaders are not necessarily “removed from public view,” and can sometimes infect whole populations with their madness. At certain times, and the Roman Empire may be one of them, reasonableness is not a reasonable approach to history.”

Caligula’s Pleasure Garden

During the four years that Caligula was Emperor, his favorite refuge was an imperial pleasure garden called Horti Lamiani. The vast residential compound spread out on the Esquiline Hill, one of the seven hills on which Rome was originally built, in the area around the current Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II. A combination estate and wildlife park, the Horti Lamiani featured orchards, fountains, terraces, a bath house adorned with precious colored marble from all over the Mediterranean, and exotic animals, some of which were used, as in the Colosseum, for private circus games. When Caligula was assassinated his body was carried to the Horti Lamiani, where he was cremated and hastily buried before being moved to the Mausoleum of Augustus. According to Suetonius, the garden was haunted by Caligula’s ghost.

Jason Horowitz, Town & Country The garden had a fountain sanctuary consecrated to the water nymphs camouflaged with hand-painted images of birds and branches, melting the border between home and garden in a court culture where little was as it seemed. The empire’s most expensive colored marble — the porphyry that gave us imperial purple, giallo antico, beige breccia, white Greek — created a kaleidoscopic perimeter for the terrace gardens. [Source:Jason Horowitz, Town & Country, March 22, 2021]

“There was so much good marble that ancient artisans used it as a canvas, carving floral designs and filling the empty spaces with other marble inlays. Greek theater masks hung from the colonnade, and the columns, candelabras, and capitals were embellished with marble oak leaves or wrapped in marble ivy. Actual wild animals, including lions and bears, entertained the guests, as peacocks and deer roamed amid rosebushes, olive trees, fruit trees, and statues. Inside the villas on the grounds,-Pompeii-red frescoes covered walls that often sparkled with astonishing quantities of garnets, carnelians, and rubies.

Caligula traipsed around in silken robes and pearl — festooned slippers and, according to one of the few eyewitness accounts of the era, having surveyed all the villas and chambers, “gave orders that they should be more magnificent” and ordered up windows of “transparent stones,” all as a terrified delegation of Jews pleading for tolerance looked on. The Praetorian Guard, which eventually murdered Caligula, 41, wore brooches on their togas inset with gold and mother-of-pearl.

In the spring of 2021, Italy’s Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Cultural Activities and Tourism opened the Nymphaeum Museum of Piazza Vittorio, a subterranean gallery that showcases a section of the imperial garden that was unearthed during an excavation from 2006 to 2015. The dig, carried out beneath the rubble of a condemned 19th-century apartment complex, yielded gems, coins, ceramics, jewelry, pottery, cameo glass, a theater mask, seeds of plants such as citron, apricot and acacia that had been imported from Asia, and bones of peacocks, deer, lions, bears and ostriches. “The ruins tell extraordinary stories, starting with the animals,” said Mirella Serlorenzi, the culture ministry’s director of excavations. “It is not hard to imagine animals, some caged and some running wild, in this enchanted setting.” [Source: Franz Lidz, New York Times, January 12, 2021]

Franz Lidz wrote in the New York Times: “The objects and structural remnants on display in the museum paint a vivid picture of wealth, power and opulence. Among the stunning examples of ancient Roman artistry are elaborate mosaics and frescoes, a marble staircase, capitals of colored marble and limestone, and an imperial guard’s bronze brooch inset with gold and mother-of-pearl. “All the most refined objects and art produced in the Imperial Age turned up,” Dr. Serlorenzi said.

“The classicist Daisy Dunn said the finds were even more extravagant than scholars had anticipated. “The frescoes are incredibly ornate and of a very high decorative standard,” noted Dr. Dunn, whose book “In The Shadow of Vesuvius” is a dual biography of Pliny the Elder — a contemporary of Caligula’s — and his nephew Pliny the Younger. “Given the descriptions of Caligula’s licentious lifestyle and appetite for luxury, we might have expected the designs to be quite gauche.”

The Horti Lamiani were commissioned by Lucius Aelius Lamia, a wealthy senator and consul who bequeathed his property to the emperor, most likely during the reign of his friend Tiberius from A.D. 14 to 37. When Caligula succeeded him — it is rumored that Caligula and the Praetorian Guard prefect Macro hastened the death of Tiberius by smothering him with a pillow — he moved into the main house.

“In an evocative eyewitness account, the philosopher Philo, who visited the estate in A.D. 40 on behalf of the Jews of Alexandria, and his fellow emissaries had to trail behind Caligula as he inspected the sumptuous residences “examining the men’s rooms and the women’s rooms … and giving orders to make them more costly.” The emperor, wrote Philo, “ordered the windows to be filled up with transparent stones resembling white crystal that do not hinder the light, but which keep out the wind and the heat of the sun.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024