Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire / Christianized Roman Empire / Christianity and Judaism in the Roman Empire

JULIO-CLAUDIANS (27 B.C. – A.D. 68)

Julio-Claudians, starting with Augustus

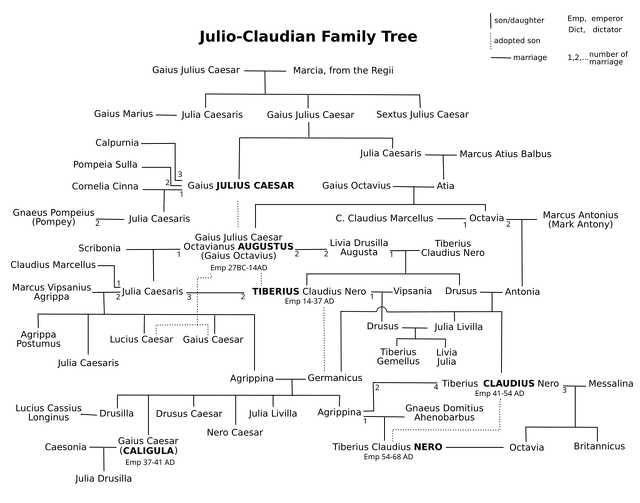

The Julio-Claudian dynasty comprised the first five Roman emperors: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero, and sometimes includes the handful largely-forgotten rulers that ruled after them. The first five emperors ruled the Roman Empire, from its creation (under Augustus, in 27 B.C.) until Emperor Nero, committed suicide (in A.D. 68). The name Julio-Claudian is derived from the two families composing the imperial dynasty: the Julii Caesares and Claudii Nerones. [Source Wikipedia]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 27 B.C., Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus was awarded the honorific title of Augustus by a decree of the Senate. So began the Roman empire and the principate of the Julio-Claudians: Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–14 A.D.), Tiberius (r. 14–37 A.D.), Gaius Germanicus, known as Caligula (r. 37–41 A.D.), Claudius (r. 41–54 A.D.), and Nero (r. 54–68 A.D.). [Source: Christopher Lightfoot, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000 \^/]

“During this time, Rome reached the height of its power and wealth; it may be seen as the golden age of Roman literature and arts, but it was also a period of imperial extravagance and notoriety. The Julio-Claudians were Roman nobles with an impressive ancestry, but their fondness for the ideals and lifestyle of the old aristocracy created conflicts of interest and duty. They cherished the memory of the Republic and wished to involve the Senate and other Roman nobles in the government. This proved impossible and eventually led to a decline in the power and effective role of the Senate, the elimination of other aristocrats through treason and conspiracy trials, and the extension of imperial control through equestrian officers and imperial freedmen. \^/

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Julio-Claudian Emperors (Classical World) by Thomas Wiedemann (1991) Amazon.com;

“Constructing Autocracy: Aristocrats and Emperors in Julio-Claudian Rome”

by Matthew B. Roller (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Ruler's House: Contesting Power and Privacy in Julio-Claudian Rome”

by Harriet Fertik (2019) Amazon.com;

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“Augustus: First Emperor of Rome” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2014); Amazon.com;

“Augustus” (New York Review Books Classics) by John Williams (1972) Amazon.com;

“Augustus, The Life of Rome's First Emperor” by Anthony Everitt (2006) Amazon.com;

“Tiberius: The Memoirs of the Emperor” by Allan Massie (1993) Amazon.com;

“Tiberius” by Robin Seager Amazon.com;

“The Successor: Tiberius and the Triumph of the Roman Empire” (2019)

by Willemijn van van Dijk Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Caesars” (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius (121 AD) Amazon.com

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C. - A.D. 476" by Michael Grant (1997) Amazon.com;

“Annals” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Histories” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World”

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire” by Alan Kreider Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

Julio-Claudian Rule

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The emperors' power rested ultimately on the army, of which they were commanders-in-chief, and they had to earn (as in the case of Claudius) its respect and loyalty. The army not only ensured their control in Rome but also helped maintain peace and prosperity in the provinces. Peace and prosperity were maintained in the provinces and foreign policy, especially under Augustus and Tiberius, relied more on diplomacy than military force. With its borders secure and a stable central government, the Roman empire enjoyed a period of prosperity, technological advance, great achievements in the arts, and flourishing trade and commerce. [Source: Christopher Lightfoot, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000 \^/]

“Under Caligula, much time and revenues were devoted to extravagant games and spectacles, while under Claudius, the empire—and especially Italy and Rome itself—benefited from the emperor's administrative reforms and enthusiasm for public works programs. Imperial expansion brought about colonization, urbanization, and extension of Roman citizenship in the provinces. The succeeding emperor, Nero, was a connoisseur and patron of the arts. He also extended the frontiers of the empire, but antagonized the upper class and failed to hold the loyalty of the Roman legions. Amid rebellion and civil war, the Julio-Claudian dynasty "came to an inglorious end with Nero's suicide in 68 A.D." \^/

The system established by Augustus was put to a severe test by the character of the men who immediately followed him. Eight of the ten emperors who followed Augustus lost their positions through violence. The emperors who made up the Julian line were often tyrannical, vicious, and a disgrace to Rome. That the empire was able to survive at all is, perhaps, another proof of the thoroughness of the work done by the first emperor. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Julio-Claudian Rulers

Vitellius, the last Julio-Claudian ruler by some reckonings

Julio-Claudian Dynasty (27 B.C.–68 A.D.)

Augustus (27 B.C.–14 A.D.)

Tiberius (14–37 A.D.)

Gaius Germanicus (Caligula) (37–41 A.D.)

Claudius (41–54 A.D.)

Nero (54–68 A.D.)

Galba (68–69 A.D.)

Otho (69 A.D.)

Vitellius (69 A.D.)

[Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, List of Rulers of the Roman Empire", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Tiberius followed the instructions left by Augustus upon his death not to undertake any expansive foreign wars. Relying more on diplomacy than military force, the empire reached an unprecedented peak of peace and prosperity. He maintained a strict economy and spent little on grandiose building projects. The most impressive sculpture begun during his reign and completed under Claudius was the Ara Pietatis, a monumental altar with classical representations that recall those on the Ara Pacis Augustae (late first century B.C.). [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Tiberius bequeathed a great surplus to his successor, Caligula, whose enormously extravagant games and spectacles eventually emptied the imperial treasury. In matters of government, Caligula favored a monarchy of Hellenistic type and accepted elaborate honors in Rome and in the provinces. The dissemination of imperial portraiture in the provinces, in sculpture, gems, and coins, was the chief means of political propaganda in the Roman empire, and all of the Julio-Claudians subscribed to the basic imperial image established by Augustus. Even Caligula, who was obsessed with his own appearance, adhered to this formula. His reign of extravagance, oppression, and treason trials ended in his assassination in 41 A.D. \^/

“Rome prospered during the succeeding reign of Claudius (Caligula's uncle), who achieved administrative efficiency by centralizing the government, taking control of the treasury, and expanding the civil service. He engaged in a vast program of public works, including new aqueducts, canals, and the development of Ostia as the port of Rome. To the Roman empire, he added Britain (43 A.D.) and the provinces of Mauritania, Thrace, Lycia, and Pamphylia. Imperial expansion brought about colonization, urbanization, and the extension of Roman citizenship in the provinces, a process begun by Julius Caesar, continued by Augustus, slowed by Tiberius, and resumed on a large scale by Claudius. \^/

“Under the next emperor, Nero, the frontiers of the empire were successfully defended and even extended. Experienced generals, such as Corbulo and Vespasian, led triumphant campaigns in Armenia, Germany, and Britain. Nero himself was more of a dilettante, and a connoisseur and patron of the arts; his coins and imperial inscriptions are among the finest ever produced in Rome. After a great fire destroyed half of Rome in 64 A.D., he spent huge sums on rebuilding the city and a vast new imperial palace, the so-called Domus Aurea, or Golden House, whose architectural forms were as innovative as they were extravagant. Nero antagonized the upper class, confiscating large private estates in Italy and putting many leading figures to death. His tendency toward Oriental despotism, as well as his failure to keep the loyalty of the Roman legions, led to civil strife and opposition to his reign.

Julio-Claudian Family and Bloodlines

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Augustus sired only one child, Julia, a daughter by his third wife, Scribonia, whom he had married for political advantage and divorced quickly. His last marriage was for love. Livia was a scion of one of the great Romans families, the Livii, and she had already been married once, to Tiberius Claudius Nero by whom she already had a son, and she was pregnant with another, Drusus, when she married Octavian in 38 B.C. They were to introduce the blood line of the Claudian gens, and hence the ruling family is labeled the Julio-Claudians in history books. But Livia had no more children. Augustus was left with Julia. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

He married her to his nephew Marcellus, and, after Marcellus' death, to his right-hand man, Marcus Agrippa, whose military talent had served Augustus well in the Civil Wars. Agrippa sired five children in less than ten years, three of them sons, Gaius, Lucius, and finally Agrippa Postumus, born after his father's death and mentally unsound. But Gaius and Lucius died young, and Augustus was left with his stepson, Tiberius. In A.D. 4, Augustus adopted him and gave him tribunician power for a ten-year term, which was renewed when the term was up and the imperium proconsulare was added to it. But at the same time as Augustus adopted him, he made him adopt Germanicus, the grandson of Augustus' sister who was married to Julia's daughter, Agrippina. When Augustus died, it was clear that if Augustus was to have a successor, it would have to be Tiberius, a Claudian, but on his death the succession would revert to Augustus' own descendants.

In fact, it did, but not as Augustus intended. Germanicus died young, leaving three sons, and Tiberius' own son, Drusus, died not long afterwards. When Tiberius died in A.D. 37, it was Germanicus' youngest son, Gaius Caligula, who succeeded, and he was the great-grandson of Augustus. When Caligula was killed Jan. 24, 41, after four years of misrule, his uncle Claudius was found hiding behind an arras. Claudius had been considered feeble-minded and harmless, and his reputation had saved his life under Caligula. He was rushed off to the praetorian camp and proclaimed emperor, while the Senate was still deliberating the succession, and some spoke for "liberty," that is, government by the Senate without an emperor. But they reached no decision. The people demonstrated for Claudius, and the Senate had little choice but to accept him. He owed the imperial office to the praetorian guard, and acknowledged his debt by giving the guardsmen handsome gratuities: a prudent move under the circumstances, but it set a hurtful example that later emperors had to follow. It made brief reigns profitable. On Claudius' death, his successor was Nero (54–68). Whatever his failings, and they were many, he was a descendant of Julia though his mother, Agrippina the Younger, and the rank-and-file of the army was loyal. When Nero died, the Julio-Claudian family became extinct.

Emma Southon wrote in National Geographic History: The Julia family (Julii) was held in high regard by the Roman people, who looked to the family as successors of Julius Caesar (Emperor Augustus was Julius Caesar’s great-nephew and adopted son). Lineage was a key factor in the match between Claudius, the fourth Roman Emperor and his third wife Messalina. The pair’s marriage formed one of the “purest” connections to the Julio-Claudian dynasty, in that it descended directly from Octavia, sister of Augustus. Tiberius, Caligula, and Claudius all descended from Livia, Augustus’s third wife, and were thereby linked also to the Claudian line. [Source: Emma Southon, National Geographic History, March 3, 2023]

Augustus (ruled 27 B.C. - A.D. 14)

Augustus was the first and arguable the greatest Roman Emperor. After Caesar's death there was five years of civil war and a bitter power struggle that resulted, 14 years later, in the accession of Augustus to the throne. Augustus was Caesar's nephew, known before he became emperor as Octavian. It has been said that the Caesar's campaign ended Republican Rome and created an empire with Augustus at the throne. The four emperors that followed Augustus were also descendants of Caesar.

Nina C. Coppolino wrote: “Unlike his great-uncle and adoptive father who was murdered by a senatorial conspiracy in 44 B.C., Augustus lived a long life, having replaced the oligarchic rule of the Roman Republic with a constitutional monarchy, controlled first by the Julio-Claudian Dynasty (31 B.C. — 68 A.D.), in which Augustus was followed by Tiberius, Claudius, Caligula, and Nero, all of whom were descended from Augustus or his wife, Livia. [Source: Nina C. Coppolino, Roman Emperors]

Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: “The civil wars that followed Caesar’s assassination were part of Octavian’s inheritance. By 30 B.C. he had eliminated his last rivals, Mark Antony and Cleopatra, and set about consolidating his power, greatly assisted by the fact that he controlled all the armies and had direct access to the wealth of Egypt, which remained his own personal possession. His other assets were his shrewdness and patience.” [Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Augustus was the Emperor of Rome during the early Christian era. Jesus was born in the 27th year of Augustus's rule. This event however was of little consequence to the Romans. Palestine was a backwater province. To achieve his ends Augustus could be quite cruel to people who got in his way. These included the banished love poet Ovid; Augustus's loyal and humane sister, Octavia, his underappreciated stepson Tiberus and Cleopatra and Marc Antony.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND HABITS factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS BECOMES EMPEROR factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS AS EMPEROR OF ROME factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS POLICIES AND REFORMS factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS, PAX ROMANA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

Livia, Wife of Augustus and Mother of Tiberius

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Tradition decreed that the Roman emperor had to be a man, but several women wielded power behind the imperial throne even if they did not rule directly. "According to Tacitus's account, it was Livia, wife of Augustus and mother of Tiberius, who was thought by many to have determined the first transition of imperial power, by removing [murdering] all potential heirs who were close of Augustus, thereby paving the way for her own son," MIT historian William Broadhead told Live Science. Tiberius was Livia's son from her previous marriage, so he was not the obvious heir to the throne. But he became Rome's second emperor upon Augustus' death in A.D. 14, thanks to Livia's actions and marriage to Augustus. [Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, August 15, 2022]

Augustus had three wives. He divorced his first wife Scribonia because of a”moral perversity of hers." Livia Drusilla, his cruel second wife, was featured in Robert Graves novel "I Claudius." She was pregnant with another man's child when they met and married Augustus three days after the baby was born. She found slave girls to send to her husband's chamber and looked the other way when he had affairs with the wives of other politicians. Livia proved to be an indispensable member of Augustus's regime but was suspected of scheming — and much worse — on behalf of her sons from her previous marriage.

Augustus’s Effort to Choose a Successor

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “In 23 B.C. Augustus, ill and expecting his demise to come at any moment, gave his signet ring to his friend, general, and later M. Vipsanius Agrippa, while at the same time he entrusted the consul, Piso, with the custody of his personal papers. This was an indication, albeit somewhat ambiguous, that Augustus intended Agrippa to be the emergency successor in the event of his death in 23 B.C. . However, his hopes at that time were truly centered on the man who was then married to Julia, Augustus' daughter by his second wife (Scribonia; cf. Suet. Aug. 62 for his brief first marriage to Claudia); this was his nephew M. Claudius Marcellus, the son of Augustus' sister Octavia. The hopes for Marcellus were dashed by his untimely death at the age of 20 in 23 B.C., an event lamented by the poets (Virg. Aen. 6. 860-886), and Augustus promptly married Julia to Agrippa. So far his machinations illustrate the difficulty of separating the office of the Princeps, in this early stage, from the familial wealth and position of Caesar and Augustus. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Julia's marriage to Agrippa started well. She gave birth to sons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, in 20 and 17 B.C. (Dio 54. 8 and 18), then two daughters (a Julia who died young, and that Agrippina later known as the Elder), and finally in 12 B.C. another son (Agrippa Postumus). The success of this union, together with the apparently high personal regard in which Augustus held Agrippa, caused him to mark that man out as his heir apparent. In 18 B.C. Agrippa became Augustus' colleague in the tribunician power, and his prominence throughout the period is attested by his appearance on the coins; in 13 B.C. his tribunician power was renewed, and he also held imperium (maius? cf. the fragment of a Greek translation of Augustus' funeral oration for Agrippa preserved on papyrus, ZPE (1970) 226 = Sherk 12) in the provinces. Meanwhile his sons, Gaius and Lucius, were themselves singled out for special honors. Augustus adopted them himself and gave them the honorary title of principes iuventutis. The existence of Gaius and Lucius softened the blow when Agrippa, too, predeceased the princeps in 12 BC. A letter of Augustus to Gaius from A.D. 1, preserved by Aulus Gellius, included these lines: ‘I beg the gods that whatever time I have left might pass with all of us in good health and with the state in the happiest condition, and with the two of you behaving like men and succeeding to my post of honor. (Attic Nights 15.7.3) ^*^

“In 6 B.C. there was agitation at Rome for Gaius Caesar to be made consul (Dio 55.9.2) and Augustus responded, with an outward show of reluctance at the transgression of Republican limitations, by designating him consul for A.D. 1 and his brother Lucius consul for A.D. 4; Gaius was made a pontifex and Lucius an augur. A flood of coinage proclaimed their status as heirs apparent. When Lucius died in A.D. 2, there was still the hope of Gaius, but he too passed away two years later.” ^*^

Tiberius (A.D. 14-37)

Tiberus (ruled from A.D. 14-37) was known for hedonism, decadence and cruelty. The adopted stepson of Augustus, he reportedly had a servant named "Sphincter;" tossed lovers that displeased him off a 1,000-foot cliff at Capri — the island near present-day Naples — and changed laws on execution of virgins that decreed that condemned virgins should be deflowered by their executioners before their sentence was carried out.

According to Tacitus and Suetonius, Tiberus was once presented a fish from a local fisherman, who was then promptly beaten with the fish. Afterwards the fisherman commented he was glad he didn't give the large crab he caught to the emperor. Tiberus overheard this and ordered the man to be beaten with the crab. Tiberus spent his last years in a palace on Capri.

death of Tiberius

Despite this, of the four Julian emperors who succeeded Augustus, Tiberius was perhaps the ablest. He had already shown his ability as a general; and having been adopted by Augustus and associated with him in the government, he was prepared to carry out the policy already laid down. But in his personal character he presented a strong contrast to his predecessor. Instead of being generous and conciliatory, he was cruel and tyrannical to those with whom he was brought into personal relations. But we must distinguish between the way in which he treated his enemies and the way in which he ruled the empire. He had a certain sense of duty, and tried to maintain the authority which devolved upon him. If he could not accomplish this by the winning ways of Augustus, he could do it by more severe methods. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Tiberius followed the instructions left by Augustus upon his death not to undertake any expansive foreign wars. Relying more on diplomacy than military force, the empire reached an unprecedented peak of peace and prosperity. He maintained a strict economy and spent little on grandiose building projects. The most impressive sculpture begun during his reign and completed under Claudius was the Ara Pietatis, a monumental altar with classical representations that recall those on the Ara Pacis Augustae (late first century B.C.). [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org ]

Struggle for Succession After Tiberus

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Tiberius' own situation vis-a-vis his successor was no less delicate and dicey than his predecessor's had been. Tiberius could naturally be expected to favor his own son by Vipsania (whom he had divorced in order to marry Julia), Drusus Caesar. But he had promised Augustus that he would adopt instead his brother's son, Germanicus Caesar, who in 14 was in command of a large army on the Rhine frontier, and who was also married to Augustus' granddaughter, Agrippina the elder. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Germanicus' death left the way clear for Tiberius' own son Drusus Caesar; it also sparked a dangerous rivalry between the emperor and the elder Agrippina, Germanicus' widow. After Drusus' death in A.D. 23, the "official" candidate for the succession was Drusus Caesar, the son of Agrippina, then 30 years old. But the enmity between Tiberius and Agrippina continued; part of the problem was that she preferred her younger son, Nero Caesar (then 29). Both of these youths disappeared from the scene after M. Aelius Sejanus, the commander of the praetorian guard, convinced Tiberius that Agrippina was plotting to murder him and replace him with Nero (it is suggestive that Drusus was allowed to remain in Rome for a year before following his mother and brother into exile). Their brother Gaius, however, who was too young to be any sort of a threat, was kept on and went to live with Tiberius in his quasi-retirement at Capri. Meanwhile Sejanus was plotting to secure the succession for himself (for his power move in consolidating the praetorian guard into one barracks, see Tac. Ann. 4.2); although Tiberius did share the consulship with him, he never granted Sejanus the tribunician power and seems never to have contemplated him as a possible candidate. ^*^

“After Sejanus fell, the victim of his own machinations, Tiberius remained in retirement at Capri. The choice of possible successors was now down to three. First, there was Germanicus' brother, Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus; but he was universally regarded as unsuitable, and he kept himself out of politics, at least as long as he could. Second, there was Tiberius' own grandson, Drusus' son Tiberius Gemellus (born A.D. 19, cf. Ann. 2.84). And third, there was Gaius, the son of the Elder Agrippina. Tiberius wavered between these latter two by making them joint heirs to his state. In the event, after his death in 37, it was decided by the praetorian guard, which picked Gaius and brought him to the senate for confirmation. The senators made no demure and even cooperated by canceling Tiberius' will. ^*^

“Four disastrous years later Gaius was dead, by a conspiracy with senatorial backing. The accession of Claudius illustrates an important stage in the development of the Principate. First, we learn from Suetonius (Claud. 10; Tacitus does not pick up until A.D. 47) that the intention of the senators had been to restore the Republic, but that this was foiled when a riotous crowd outside the Curia demanded a monarchy, and second, that the decision was not put into place quickly enough because there was opposition among the senators themselves. The point is that on the occasion, as never again in the history of the Empire, the system itself of the Principate was tested and it held fast. It had become truly institutionalized.” ^*^

Caligula

Caligula (born A.D. 12, ruled A.D. 37-41) had a great passion for women, gladiator games, chariot racing, theatrical performances, ships and violence. He liked to watch people being tortured and executed and murdered his brother along with countless others. He lasted only four years in power before he was assassinated. Some scholars dismiss accounts of Caligula's excesses as exaggerated by historians and a public that didn't like him. Other than the great ship he built there is no archaeological evidence that he spent more or was more wasteful than other emperors.

Andrew Handley wrote for Listverse:“He was one of the first emperors with truly unlimited power, and he often referred to himself as a god—he even appointed his horse as a priest. Caligula also appeared in public dressed in women’s clothing, and reportedly told his guards to use call-signs that were blatantly feminine, such as “Kiss me quick.” [Source: Andrew Handley, Listverse, February 8, 2013]

The reign of Caligula, which was fortunately limited to the brief space of four years, shows to us the perils inherent in a despotic form of government that permitted a madman to rule the civilized world. The Roman Empire had no provision by which any prince could be held responsible, either to law or to reason. A cruel tyrant could revel in blood, or a maniac could indulge in the wildest excesses without restraint. The only limit to such a despotism was assassination; and by this severe method the reign of Caligula was brought to an end. \~\

See Separate Article: CALIGULA (ruled from A.D. 37-41) europe.factsanddetails.com

Claudius

Rome prospered during the reign Claudius I (10 B.C-45 A.D.), Caligula's uncle. Regarded as a crippled, uncouth scholar and characterized by some as a "dim-witted oaf" because he stuttered and had the habit of drooling, Claudius improved Rome’s administrative efficiency by centralizing the government, taking control of the treasury, and expanding the civil service. He wrote 20 books about Etruscan history and primers on gambling. He also wrote a play in Greek and added three letter to the Roman alphabet.

Suetonius wrote: “He possessed majesty and dignity of appearance, but only when he was standing still or sitting, and especially when he was lying down; for he was tall but not slender, with an attractive face, becoming white hair, and a full neck. But when he walked, his weak knees gave way under him, and he had many disagreeable traits both in his lighter moments and when he was engaged in business; his laughter was unseemly and his anger still more disgusting, for he would foam at the mouth and trickle at the nose; he stammered besides and his head was very shaky at all times, but especially when he made the least exertion. Though previously his health was bad, it was excellent while he was emperor, except for attacks of heartburn which he said all but drove him to suicide.”[Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum:Claudius” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Claudius”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Claudius came under the influence of the members of his household—his wives and freedmen. The intrigues and crimes of his wife Messalina, and of his niece Agrippina, whom he married after the death of Messalina, were a scandal to Roman society. So far as he was influenced by these abandoned women, his reign was a disgrace. But the same can scarcely be said of the freedmen of his household—Narcissus, his secretary; Pallas, the keeper of accounts; and Polybius, the director of his studies. These men were educated Greeks, and although they were called menials, he took them into his confidence and received benefit from their advice. Indeed, it has been said that “from Claudius dates the transformation of Caesar’s household servants into ministers of state.” [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

See Separate Article: CLAUDIUS (ruled from A.D. 37-54) europe.factsanddetails.com

Nero

Nero (A.D. 37-68) was the fifth emperor of Rome, ruling from A.D. 54 to 68. He became the Roman emperor when he was seventeen, the youngest ever at that time. Nero's real name was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He is known mainly for being a cruel wacko but in many ways he left the Roman Empire better off than when arrived.

Nero was the grandson of Germanicus and a descendant of Augustus. He was proclaimed Emperor by the praetorians (Roman army elite) and accepted by the senate. He had been educated by the great philosopher Seneca; and his interests had been looked after by Burrhus, the able captain of the praetorian guards. His accession was hailed with gladness. He assured the senate that he would not interfere with its powers. The first five years of his reign, which are known as the “Quinquennium Neronis,” were marked by a wise and beneficent administration.

During this time he yielded to the advice and influence of Seneca and Burrhus, some scholars believe practically controlled the affairs of the empire and restrained the young prince from exercising his power to the detriment of the state. Under their influence delation (accusing or bringing charges against someone, especially by an informer) was forbidden, taxes were reduced, and the authority of the senate was respected. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

NERO (A.D. 37-68): HIS LIFE, DEATH, MOTHER AND WIVES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO (RULED A.D. 54-68) AS EMPEROR: EARLY PROMISE, REFORMS, LATER REVOLTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

GREAT FIRE OF ROME IN A.D. 64: NERO, EVIDENCE, STORIES, RUMORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO'S GOLDEN HOUSE AND THE REBUILDING ROME AFTER THE GREAT FIRE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO'S CRUELTY — TOWARDS HIS FAMILY, AIDES AND CHRISTIANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO’S BUFFOONERY, EXTRAVAGANCE AND STRANGE SEX LIFE factsanddetails.com

After Nero: Year of Three Emperors

Nero was forced to commit suicide in 68 A.D. at the age of 30. He killed himself by falling on his sword. Nero's death was followed by the Year of the Four Emperors (A.D. 69), in which Rome was lead in succession by Galba, Otho, Vitellisu and Vespasian.

With the death of Nero, the imperial line which traced its descent from Julius Caesar and Augustus became extinct. With all his prudence, Augustus had failed to provide a definite law of succession. In theory the appointment of a successor depended upon the choice of the senate, with which he was supposed to share his power. But in fact it depended quite as much upon the army, upon which his power rested for support. Whether the appointment was made by the senate or by the army, the choice had hitherto always fallen upon some member of the Julian family. But with the extinction of the Julian line, the imperial office was open to anyone. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Under such circumstances we could hardly expect anything else than a contest for the throne. Not only the praetorian guards, but the legions in the field, claimed the right to name the successor. The rival claims of different armies to place their favorite generals on the throne led to a brief period of civil war—the first to break the long peace established by Augustus. \~\

Galba (A.D. 68-69): At the time of Nero’s death, the Spanish legions had already selected their commander, Galba, for the position of emperor. Advancing upon Rome, this general was accepted by the praetorians and approved by the senate. He was a man of high birth, and with a good military record. But his career was a brief one. The legions on the Rhine revolted against him. The praetorians were discontented with his severity and small donations: He soon found a rival in Otho, the husband of the infamous Poppaea Sabina who had disgraced the reign of Nero. Otho enlisted the support of the praetorians, and Galba was murdered to give place to his rival. \~\

Otho (A.D. 69): The brief space of three months, during which Otho was emperor, cannot be called a reign, but only an attempt to reign. On his accession the new aspirant to the throne found his right immediately disputed by the legions of Spain and Gaul, which proclaimed Vitellius. The armies of these two rivals met in northern Italy, and fortune declared in favor of Vitellius. Under Otho, Nero's statues were again set up, his freedmen and household officers reinstalled, including the young castrated boy Sporus whom Nero had taken in marriage and Otho also would live intimately with. The populace acclaimed him as "Nero Otho", although Otho did not appear to like the title. [Source: \~\, Wikipedia]

Vitellius (A.D. 69): No sooner had Vitellius begun to revel in the luxuries of the palace, than the standard of revolt was again raised, this time by the legions of the East in favor of their able and popular commander, Vespasian. The events of the previous contest were now repeated; and on the same battlefield in northern Italy where Otho’s army had been defeated by that of Vitellius, the forces of Vitellius were now defeated by those of Vespasian. Afterward a severe and bloody contest took place in the streets of Rome, and Vespasian made his position secure. The only significance of these three so-called reigns, and the civil wars which attended them, is the fact that they showed the great danger to which the empire was exposed by having no regular law of succession. \~\

Vitelliusm — Gluttonous Emperor ‘Tight-Bum’

Aulus Vitellius rule from January 2 to December 20 A.D., when he was killed by supporters of his successor, Vespasian. Harry Sidebottom wrote in The Telegraph: As a youth a sexual plaything of the emperor Tiberius (earning the nickname “tight-bum”), as a young man a charioteer and gambler, Vitellius in maturity devoted himself to drunkenness and, above all, gluttony. He never fought as a gladiator, entertained divine pretentions, acted as a sexual predator, let alone indulged in incest, was only half-heartedly accused of avarice and cruelty, was not particularly sinister and murderous, or even very ambitious. Maybe the competition for infamy was just too tough. Apart from giving his name to a dish of beans in sweet and sour sauce, his main claim to cultural posterity was the use by Renaissance artists of his features for characters in paintings of Roman orgies. [Source: Harry Sidebottom, The Telegraph March 19, 2023]

Vitellius and his family make the ideal foundation on which Peter Stothard constructs an alternative history of the development of the imperial court on the Palatine Hill in the reigns of Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero. The Vitelli were not proud Republican aristocrats looking back with nostalgia to the days of freedom, when their ancestors addressed the plebs urbana in the forum, and won battles in the field against barbarian hordes. Instead the family origins were equestrian (the second rank in Roman society), from the small town of Nuceria. Far from chafing under the rule of the emperors, or providing martyrs for the opposition, they rose as imperial playmates and servants, consummate courtiers in the endless corridors and dining rooms of power.

Palatine opens in A.D. 69 with Vitellius cowering alone in a doghouse in the palace, waiting to be dragged out and butchered, before it jumps back in time to begin the family story with the death of Augustus in A.D. 14. Stothard constructs his narrative in short, sharp chapters. Each is a starting point for more general reflections: Vitellius in the kennels leads to Grattius Faliscus, the Augustan poet of hunting with dogs (canines are a recurring interest); the last moments of Augustus lead to theatricality and the stock characters of Atellan farce.

Apart from dogs, the main themes include flattery and acting, food and fables; Phaedrus and Aesop are constant companions, illuminating attitudes of mind. Together these vivid vignettes intertwine to paint an immersive and frighteningly believable picture of the rewards and perils, as well as the pervasive uncertainties, of life at the court of a capricious autocrat.As such it is reminiscent of dying days of the regime of Haile Selassie conjured up by Ryszard Kapuscinski in The Emperor (1983).

Vitellius’s Gluttony

The Emperor Vitellius had a very brief and insignificant reign (69 A. D.). He was mainly distinguished for his gormandizing and gluttony. How he enjoyed himself during his short lease of power is told by Suetonius. Probably there were a good many in Rome who would have imitated him, if given a similar opportunity.

Suetonius wrote: “Vitellius always made three meals per day, sometimes four: breakfast, dinner and supper and a drunken revel after all. This load of victuals he could bear well enough, from a custom to which he had enured himself of frequently vomiting For these several meals he would make different appointments at the houses of his friends on the same day. None ever entertained him at a less expense than 400,0000 [Arkenberg: about $570,000,000 in 1998 dollars]. [Source “Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.):Life of Vitellius (b. 15 r. 69 -d.69 A.D.) Chap. 13: The Gormandizing of the Emperor Vitellius]

The most famous was a set entertainment given him by his brother, at which were served up no less than two thousand choice fishes, and seven thousand birds. Yet even this supper he himself outdid at a feast which he gave upon the first use of a dish which had been made for him, and which from its extraordinary size he called "The Shield of Minerva." In this dish were tossed together the livers of charfish, the brains of pheasants and peacocks, with the tongues of flamingoes and the entrails of lampreys, which had been brought in ships of war as far as from the Carpathian Sea [between Crete and Rhodes] and the Spanish Straits. He was not only a man of insatiable appetite, but he would gratify it at unseasonable times, and with any garbage that came his way. Thus at a sacrifice he would snatch from the fire the flesh and cakes and eat them on the spot. When he traveled, he did the same at inns upon the road, whether the meat was fresh dressed and hot, or whether it had been left from the day before and was half eaten.

Jesus and the Romans

Christ on the Cross by Rubens, with some Roman soldiers nearby

Jesus was alive during the reigns of Augustus (42 B.C. - A.D. 14) and Tiberus ( 14-37). At the time of Christ, Palestine (present-day Israel) was a poorly-run, repressive Roman colony that had been conquered by Pompey in 63 B.C. After the conquest Palestine was run by a Roman-Jewish government under Herod the Great (37-4 B.C.) who enjoyed considerable autonomy and ruled in such a way that both the Romans and local population were reasonably happy despite his sometimes despotic ways.

The rulers after Herod — namely Archelaus, who inherited a third of Herod’s land, including Judea and Jerusalem — were not so good. After 10 years Roman prefects took over Archelaus’s territory. The other portions of Herod’s former lands, including Jesus’s state of Galilee remained under Jewish rule. This arrangement remained until the Roman crackdown after the Jewish revolt and the destruction of the Second Temple in A.D. 70.

Herod the Great was a Jewish leader installed by the Romans. Regarded as puppet king of the Roman Senate, he took power in 37 B.C. and ruled until around 4 B.C. and served under Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and the Emperor Augustus. He is remembered most for building the Great Temple for the Jews in Jerusalem and ordering the death of male children in Bethlehem after Jesus was born. His son Herod Antipas was involved in Jesus’s trial. He was the ruler of Judea at time of the death of John the Baptist and Jesus.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JESUS'S LIFE: HIS YOUTH, BAPTISM, FOLLOWERS, EVENTS africame.factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF THE JEWS AROUND THE TIME OF JESUS factsanddetails.com

HOLY LAND AT THE TIME OF CHRIST factsanddetails.com

LAST SUPPER, ARREST OF JESUS AND EVENTS BEFOREHAND africame.factsanddetails.com

TRIALS OF JESUS factsanddetails.com

St. Paul and the Persecution of Christians

Nero allegedly ordered the slaughter of Christians. Among them, according to tradition, were the apostles Peter and Paul. Christians, wrote Tacitus, "were nailed on crosses...sewn up in the skins of wild beasts, and exposed to the fury of dogs; others again, smeared over with combustible materials, were used as torches to illuminate the night."

Nero began persecuting Christians on the grounds of disloyalty and blamed them, along with Jews, for the great fire in Rome in A.D. 64, something which he is believed to have been was involved in. Tacitus wrote that before the killing of Christians, Nero used them to amuse the masses. Some were dressed in furs, to be killed by dogs. Others were crucified. Still others were set on fire. Although some persecution of Christian is believed to have occurred, and some it was very cruel, the extent of it has been wildly exaggerated. Most of the victims were bishops or other male leaders. Nero is believed to have accused the Christians of starting the Rome fire in order to shield himself from the suspicion of setting the fire himself.

Paul Addresses a Crowd Before His Arrest The height of the persecution of Christians was not during the reign of Nero, but much later. Domitian, Marcus Aurelius and Valerian all brutalized Christians after A.D. 150, when Christians held many high positions and presented a threat as "state within a state." In A.D. 202 the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus made baptism a criminal act. In A.D. 250 Emperor Decius increased the persecution of Christians.

According to the traditional story, in A.D. 67, in the last year of Nero’s reign, St. Peter was hung upside down and beheaded at the Circus Maximus during a wave of brutal anti-Christian persecution after the burning of Rome. His brutal treatment was partly of the result of his request not to be crucified, because he didn't consider himself worthy of the treatment of Jesus. After Peter died, it is said, his body was taken to a burial ground, situated where St. Peter's cathedral now stands. His body was entombed and later secretly worshiped.

It is not exactly clear what happened to St. Paul but it is believed that he was martyred in A.D. 64, the year that Nero blamed the great fire of Rome on the Christian and Jews. Before he was killed St. Paul invoked his right as a Roman citizen to be beheaded. His wish was granted. According to some, Paul was martyred at the site occupied by the Monastery of the Three Fountains in Rome. The Cathedral of St. John Lateran, the oldest Christian basilica in Rome, founded by Constantine on A.D. 314, contains reliquaries said to hold the heads of St. Paul and St. Peter and the chopped off finger doubting Thomas stuck in Jesus' wound.

See Separate Article: ST. PAUL'S TRAVELS AND MISSIONARY WORK europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024