Home | Category: Age of Augustus / Government and Justice

AUGUSTUS’S POLITICAL ACHIEVEMENTS

Nina C. Coppolino wrote: “Through his gradual efforts, and through the circumstances of his era, Augustus ruled Rome alone for nearly a half-century (31 B.C.- 14 A.D.), and he set for all his successors the institutional and ideological foundations of the Roman Empire. The broad bases of his power were the army, whose loyalty was maintained by money and land-grants at retirement, and Tiberius’s apparently genuine support of many people, who wanted at any constitutional cost an end to the factional bloodshed of the late Republican civil wars; the nobles retained niches in the regular operation of the still prestigious political administration or in military roles, property was ultimately secured, administrative roles were more easily filled by some increased social mobility among the ranks and classes, and the populace (once fed) was ostensibly defended by the tribunicia potestas with which Augustus legitimized his rule, and which finally became the official rubric under which the state was run for centuries. The innovative outcome of Augustus' rule was the acquisition of sole power at Rome and abroad by the assumption of traditionally distributed powers found in long-standing Roman magistracies, military commands, state religious honors, patronage, family connections, and personal influence. [Source: Nina C. Coppolino, Roman Emperors ]

Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: “Many reforms were necessary, but he rarely imposed his will, and worked by legal means. In order to oversee his initial reforms, he entered on his fourth consulship in 30 B.C. and held it every year until 23 B.C. But the most important source of his power was that of the tribunes, which gave him the right of veto over any proposals. [Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“In 27 B.C., he restored control of the republic to the Senate, ostensibly reverting to the old order, with annually elected magistrates, the senators sharing responsibility for government, and no single individual with supreme power. But it was a republic in name only. The reality was that Octavian emerged with the honorary title 'Augustus' and the control, via his legates, of all the provinces with armies. Augustus converted the republican citizen levy into a standing army, established regular pay and terms of service for soldiers, and a pension scheme for veterans. Gradually by his authority and influence he became the principal fount of law, he controlled state finance, foreign policy and religion, and he shaped Roman society as the republic was transformed into the empire. In brief, he became the first emperor.” |::|

Books: “Augustus: First Emperor of Rome” by Adrian Goldsworthy (Yale University Press, 2014); “Augustus, The Life of Rome's First Emperor” by Anthony Everitt (Random House, 2006)

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, FAMILY, SOURCES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS'S CHARACTER, LIFESTYLE, APPEARANCE AND HABITS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS BECOMES EMPEROR OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS'S POLICIES AND REFORMS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS, PAX ROMANA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS'S ACCOMPLISHMENTS: BUILDING CAMPAIGN, PUBLIC WORKS, THE ARTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS'S LEGACY, WILL AND EFFORT TO PREPARE A SUCCESSOR europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Acts of the Divine Augustus (Res Gestae Divi Augusti) MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Augustus” (New York Review Books Classics) by John Williams (1972) Amazon.com;

“Augustus: First Emperor of Rome” by Adrian Goldsworthy (Yale University Press, 2014); Amazon.com;

“Augustus, The Life of Rome's First Emperor” by Anthony Everitt (Random House, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Augustus and the Family at the Birth of the Roman Empire” by Beth Severy (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Roman History: The Reign of Augustus” (Penguin Classics) by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Augustus: The Biography” by Jochen Bleicken, Anthea Bell Amazon.com;

“The Age of Augustus”by Werner Eck (Author) Amazon.com;

“Augustus at War: The Struggle for the Pax Augusta” by Lindsay Powell (2016) Amazon.com

“Marcus Agrippa: Right-Hand Man of Caesar Augustus” by Lindsay Powell (2023) Amazon.com;

“Octavian: Rise to Power: The Early Years of Caesar” by Patrick J. Parrelli (2015) Amazon.com;

“Augustan Culture” by Karl Galinsky (1996) Amazon.com

“Augustan Rome” by A Wallace-Hadrill, (Classical World, 1998) Amazon.com;

“Power of Images in the Age of Augustus” by Paul Zanker and Alan Shapiro (1988) Amazon.com

“The Museum of Augustus: The Temple of Apollo in Pompeii, the Portico of Philippus in Rome, and Latin Poetry” by Peter Heslin (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire” by Anthony Everitt (2013) Amazon.com;

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Rome: An Empire's Story” by Greg Woolf (2012) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

Augustus as Emperor

Augustus (Octavian) Octavia officially became emperor of Rome at the age of 35 in 27 B.C., three years after the Battle of Actium (he had been the unofficial leader of Rome since 31 B.C.). He was given the formal title of Augustus Caesar, a named denoting majesty and dignity, and enthroned in a ceremony that implied he was at last semi-divine. Augustus reportedly selected the name Augustus because he defeated his toughest enemy, Egypt and Syria under Antony and Cleopatra, in the month of August.

Augustus began his career as a firm believer in Republicanism but ended it as an absolute dictator. Historians mark the year he took power, 31 B.C., as the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of Imperial Rome. Even so Augustus mostly ruled benevolently like a simple public magistrate and "advocated moderation and virtues." Under Augustus the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. Large landowners swindled small land owners out of the land. There was a mass migration of rural people to Rome. People went hungry and were homeless.

There was an aura of ambiguity about the principate (political regime) of which Augustus governed under. Augustus was both princeps (first citizen) and imperator (generalissimo); the first title denoted prestige and influence within the customary constitution of Rome, and the second denoted military power. He enjoyed the confidence of the masses; when there were floods, a food shortage, and an epidemic in 22 B.C., they rioted to make him accept a dictatorship. The army was loyal. The commanders Augustus appointed were men whom he could trust; when he could, he chose members of the imperial family. The provinces were better governed, and had no reason to regret the passing of the old republic. The people accepted peace after a generation of civil war with relief and gratitude. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Augustus delivered Rome to the hands of the emperors by destroying, coopting and intimidating the old governing elite into submission. The once powerful Senate was stripped of much of its power and became something along the lines of a rubber stamp legislature like that in China today. Augustus paid lip service to its republican traditions" and "legitimized his power under a facade of constitutional authority" and kept up appearances by acting as the princeps, first citizen. "It was on the dignity of the senate," Gibbon wrote, "that Augustus and his successors founded their new empire." The result he wrote was "an absolute monarchy disguised by the forms of a commonwealth,"

Titles and Powers of Augustus

Soon after returning to Rome in 27 B.C., Augustus resigned the powers which he had hitherto exercised, giving “back the commonwealth into the hands of the senate and the people”. The first official title which he then received was the surname Augustus, bestowed by the senate in recognition of his dignity and his services to the state, He then received the proconsular power (imperium proconsulare) over all the frontier provinces, or those which required the presence of an army. He had also conferred upon himself the tribunician power tribunicia potestas,by which he became the protector of the people. He moreover was made pontifex maximus, and received the title of Pater Patriae. Although Augustus did not receive the permanent titles of consul and censor, he occasionally assumed, or had temporarily assigned to himself, the duties of these offices. He still retained the title of Imperator, which gave him the command of the army. But the title which Augustus chose to indicate his real position was that of Princeps Civitatis, or “the first citizen of the state,” The new “prince” thus desired himself to be looked upon as a magistrate rather than a monarch—a citizen who had received a trust rather than a ruler governing in his own name. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Suetonius wrote: “The whole body of citizens with a sudden unanimous impulse proffered him the title of Pater Patriae ["Father of his Country"]; first the commons, by a deputation sent to Antium, and then, because he declined it, again at Rome as he entered the theatre, which they attended in throngs, all wearing laurel wreaths; the Senate afterwards in the House, not by a decree or by acclamation, but through Valerius Messala. He, speaking for the whole body, said: "Good fortune and divine favour attend you and your house, Caesar Augustus; for thus we feel that we are praying for lasting prosperity for our country and happiness for our city. The Senate in accord with the people of Rome hails you Father of your Country." Then Augustus with tears in his eyes replied as follows (and I have given his exact words, as I did those of Messala): "Having attained my highest hopes, Fathers of the Senate, what more have I to ask of the immortal gods than that I may retain this same unanimous approval of yours to the very end of my life." [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum--Divus Augustus” (“The Lives of the Caesars--The Deified Augustus”), written A.D. c. 110, “Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum,” 2 Vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 123-287]

“In honour of his physician, Antonius Musa, through whose care he had recovered from a dangerous illness, a sum of money was raised and Musa's statue set up beside that of Aesculapius. Some householders provided in their wills that their heirs should drive victims to the Capitol and pay a thank-offering in their behalf, because Augustus had survived them, and that a placard to this effect should be carried before them. Some of the Italian cities made the day on which he first visited them the beginning of their year. Many of the provinces, in addition to temples and altars, established quinquennial games in his honour in almost every one of their towns.

“His friends and allies among the kings each in his own realm founded a city called Caesarea, and all joined in a plan to contribute the funds for finishing the temple of Jupiter Olympius, which was begun at Athens in ancient days, and to dedicate it to his Genius [i.e., one's tutelary divinity, or familiar spirit, closely identified with the person himself]; and they would often leave their kingdoms and show him the attentions usual in dependents, clad in the toga and without the emblems of royalty, not only at Rome, but even when he was travelling through the provinces.:

Augustus’s Advisors

Nina C. Coppolino wrote: “There was not a dyarchic division of power between the senate and Augustus. Augustus ultimately had the power of all the legions abroad and of the standing army of 9,000 soldiers in the Praetorian Guard at Rome and in the Italian towns. The senate, however, had important judicial, financial, and probouleutic functions at home, and it was the source of provincial governorships. The basic social hierarchy of Rome was maintained with the senatorial nobility at the top; the equites, who were of the same economic class but lacked the prestige of the senate, still staffed the jury-courts and junior army and procuratorial posts, but now they also got provincial commands. Around Augustus there was not so much a 'party' of political alliance, as a group of friends or clients who were confidants by the personal choice of Augustus. Most important for advisory, administrative, and military positions was the dynastic network of the imperial family. [Source: Nina C. Coppolino, Roman Emperors]

The remarkable prosperity that attended the reign of Augustus has caused this age to be called by his name. The glory of this period is largely due to the wise policy of Augustus himself; but in his work he was greatly assisted by two men, whose names are closely linked to his own. These men were Agrippa and Maecenas. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Agrippa had been from boyhood one of the most intimate friends of Augustus, and during the trying times of the later republic had constantly aided him by his counsel and his sword. The victories of Augustus before and after he came to power were largely due to this able general. By his artistic ability Agrippa also contributed much to the architectural splendor of Rome.\~\

The man who shared with Agrippa the favor and confidence of Augustus was Maecenas, a wise statesman and patron of literature. It was by the advice of Maecenas that many of the important reforms of Augustus were adopted and carried out. But the greatest honor is due to Maecenas for encouraging those men whose writings made this period one of the “golden ages” of the world’s literature. It was chiefly the encouragement given to architecture and literature which made the reign of Augustus an epoch in civilization. \~\

Augustus: the Just Ruler

Suetonius wrote: “The evidences of his clemency and moderation are numerous and strong. Not to give the full list of the men of the opposite faction whom he not only pardoned and spared, but allowed to hold high positions in the state, I may say that he thought it enough to punish two plebeians, Junius Novatus and Cassius Patavinus, with a fine and with a mild form of banishment respectively, although the former had circulated a most scathing letter about him under the name of the young Agrippa, while the latter had openly declared at a large dinner party that he lacked neither the earnest desire nor the courage to kill him. Again,when he was hearing a case against AemiliusAelianus of Corduba and it was made the chief offence, amongst other charges, that he was in the habit of expressing a bad opinion of Caesar, Augustus turned to the accuser with assumed anger and said: "I wish you could prove the truth of that. I'll let Aelianus know that I have a tongue as well as he, for I'll say even more about him;" and he made no further inquiry either at the time or afterwards. When Tiberius complained to him of the same thing in a letter, but in more forcible language, he replied as follows: "My dear Tiberius, do not be carried away by the ardour of youth in this matter, or take it too much to heart that anyone speak evil of me; we must be content if we can stop anyone from doing evil to us." [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum--Divus Augustus” (“The Lives of the Caesars--The Deified Augustus”), written A.D. c. 110, “Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum,” 2 Vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 123-287]

“Although well aware that it was usual to vote temples even to proconsuls, he would not accept one even in a province save jointly in his own name and that of Rome. In the city itself he refused this honour most emphatically, even melting down the silver statues which had been set up in his honour in former times and with the money coined from them dedicating golden tripods to Apollo of the Palatine. When the people did their best to force the dictatorship upon him, he knelt down, threw off his toga from his shoulders and with bare breast begged them not to insist.

“He always shrank from the title of Dominus [ "Lord" or "Master"] as reproachful and insulting. When the words "O just and gracious Lord!" were uttered in a farce at which he was a spectator and all the people sprang to their feet and applauded as if they were said of him, he at once checked their unseemly flattery by look and gesture, and on the following day sharply reproved them in an edict. After that he would not suffer himself to be called "Sire" even by his children or his grandchildren either in jest or earnest, and he forbade them to use such flattering terms even among themselves. He did not if he could help it leave or enter any city or town except in the evening or at night, to avoid disturbing anyone by the obligations of ceremony. In his consulship he commonly went through the streets on foot, and when he was not consul, generally in a closed litter. His morning receptions were open to all, including even the commons, and he met the requests of those who approached him with great affability, jocosely reproving one man because he presented a petition to him with as much hesitation "as he would a penny to an elephant." On the day of a meeting of the Senate he always greeted the members in the House and in their seats, calling each man by name without a prompter; and when he left the House, he used to take leave of them in the same manner, while they remained seated. He exchanged social calls with many, and did not cease to attend all their anniversaries, until he was well on in years and was once incommoded by the crowd on the day of a betrothal. When Gallus Cerrinius, a senator with whom he was not at all intimate, had suddenly become blind and had therefore resolved to end his life by starvation, Augustus called on him and by his consoling words induced him to live.”

Augustus’s Dealings with the Senate

The census that Augustus conducted in 28 B.C. registered 4,063,000 citizens. J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: He tried to reduce the numbers in the Senate which had ballooned to over a thousand, and expelled some 150, but he failed to bring the number down to the Sullan figure of 600....Augustus' accomplishment displays a nice balance between respect for senatorial traditions and eagerness to harness the abilities and loyalty of new blood. He chose his highest civil and military officers from among the senators, and three times (29/8, 18, 13 B.C.) he purged the rolls of the senate to rid it of undesirable members. For the first time he set a property qualification: either 800 thousand sesterces, according to Suetonius or 400 thousand (Cassius Dio) but he raised it periodically and at the start of Tiberius' reign it stood at one million. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com] [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Suetonius wrote: ““As he was speaking in the Senate someone said to him: "I did not understand," and another: "I would contradict you if I had an opportunity." Several times when he was rushing from the House in anger at the excessive bickering of the disputants, some shouted after him: "Senators ought to have the right of speaking their mind on public affairs." At the selection of Senators when each member chose another, Antistius Labeo named Marcus Lepidus, an old enemy of the emperor's who was at the time in banishment; and when Augustus asked him whether there were not others more deserving of the honor, Labeo replied that every man had his own opinion. Yet for all that no one suffered for his freedom of speech or insolence.” [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum — Divus Augustus” (“The Lives of the Caesars — The Deified Augustus”), written A.D. c. 110, “Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum,” 2 Vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 123-287]

“He did not even dread the lampoons against him which were scattered in the Senate house, but took great pains to refute them; and without trying to discover the authors, he merely proposed that thereafter such as published notes or verses defamatory of anyone under a false name should be called to account.

“When he was assailed with scurrilous or spiteful jests by certain men, he made reply in a public proclamation; yet he vetoed a law to check freedom of speech in wills [the Romans in their wills often expressed their opinion freely about public men and affairs]. Whenever he took part in the election of magistrates, he went the round of the tribes with his candidates and appealed for them in the traditional manner. He also cast his own vote in his tribe, as one of the people. When he gave testimony in court, he was most patient in submitting to questions and even to contradiction. He made his forum narrower than he had planned, because he did not venture to eject the owners of the neighbouring houses. He never recommended his sons for office without adding "If they be worthy of it." When they were still under age and the audience at the theatre rose as one man in their honour, and stood up and applauded them, he expressed strong disapproval. He wished his friends to be prominent and influential in the state, but to be bound by the same laws as the rest and equally liable to prosecution. When Nonius Asprenas, a close friend of his, was meeting a charge of poisoning made by Cassius Severus, Augustus asked the Senate what they thought he ought to do; for he hesitated, he said for fear that if he should support him, it might be thought that he was shielding a guilty man, but if he failed to do so, that he was proving false to a friend and prejudicing his case. Then, since all approved of his appearing in the case, he sat on the benches [the moveable seats provided for the advocates, witnesses, etc.] for several hours, but in silence and without even speaking in praise of the defendant. He did however defend some of his clients, for instance a certain Scutarius, one of his former officers, who was accused of slander. But he secured the acquittal of no more than one single man, and then only by entreaty, making a successful appeal to the accuser in the presence of the jurors; this was Castricius, through whom he had learned of Murena's conspiracy.

“It may readily be imagined how much he was beloved because of this admirable conduct. I say nothing of decrees of the Senate, which might seem to have been dictated by necessity or by awe. The Roman knights celebrated his birthday of their own accord by common consent, and always for two successive days [September 22 and 23]. All sorts and conditions of men, in fulfilment of a vow for his welfare, each year threw a small coin into the Lacus Curtius, and also brought a New Year's gift to the Capitol on the Kalends of January, even when he was away from Rome. With this sum he bought and dedicated in each of the city wards costly statues of the gods, such as Apollo Sandaliarius, Jupiter Tragoedus, and others. To rebuild his house on the Palatine, which had been destroyed by fire, the veterans, the collegia, the tribes, and even individuals of other conditions gladly contributed money, each according to his means; but he merely took a little from each pile as a matter of form, not more than a denarius from any of them. On his return from a province they received him not only with prayers and good wishes, but with songs. It was the rule, too, that whenever he entered the city, no one should suffer punishment.”

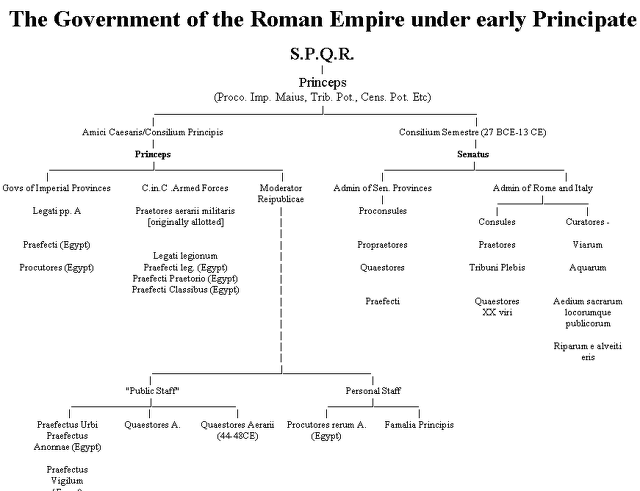

Bureaucracy and Administration Under Augustus

In accordance with his general policy Augustus did not interfere with the old republican offices and magistrates, but allowed them to remain as undisturbed as possible. The consuls, praetors, quaestors, and other officers continued to be elected just as they had been before. But the emperor did not generally use these magistrates to carry out the details of his administration. This was performed by other officers appointed by himself. The position of the old republican magistrates was rather one of honor than one of executive responsibility. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Suetonius wrote: “To enable more men to take part in the administration of the State, he devised new offices: the charge of public buildings, of the roads, of the aqueducts, of the channel of the Tiber, of the distribution of grain to the people, as well as the prefecture of the city, a board of three for choosing Senators, and another for reviewing the companies of the knights whenever it should be necessary. He appointed censors, an office which had long been discontinued. He increased the number of praetors. He also demanded that whenever the consulship was conferred on him, he should have two colleagues instead of one; but this was not granted, since all cried out that it was a sufficient offence to his supreme dignity that he held the office with another and not alone. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum — Divus Augustus” (“The Lives of the Caesars — The Deified Augustus”), written A.D. c. 110, “Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum,” 2 Vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 123-287]

“He was not less generous in honouring martial prowess, for he had regular triumphs voted to above thirty generals, and the triumphal regalia to somewhat more than that number. To enable Senators' sons to gain an earlier acquaintance with public business, he allowed them to assume the broad purple stripe immediately after the gown of manhood and to attend meetings of the Senate; and when they began their military career, he gave them not merely a tribunate in a legion, but the command of a division of cavalry as well; and to furnish all of them with experience in camp life, he usually appointed two Senators' sons to command each division. He reviewed the companies of knights at frequent intervals, reviving the custom of the procession after long disuse. But he would not allow an accuser to force anyone to dismount as he rode by, as was often done in the past; and he permitted those who were conspicuous because of old age or any bodily infirmity to send on their horses in the review, and come on foot to answer to their names whenever they were summoned. Later he excused those who were over thirty-five years of age and did not wish to retain their horses from formally surrendering them.

“XIX. Having obtained ten assistants from the Senate, he compelled each knight to render an account of his life, punishing some of those whose conduct was scandalous and degrading others; but the greater part he reprimanded with varying degrees of severity. The mildest form of reprimand was to hand them a pair of tablets publicly, which they were to read in silence on the spot. He censured some because they had borrowed money at low interest and invested it at a higher rate.

Assemblies of the People and Tribunes Under Augustus

Augustus did not formally take away from the popular assemblies their legislative power, but occasionally submitted to them laws for their approval. This was, however, hardly more than a discreet concession to custom. The people in their present unwieldy assemblies, the emperor did not regard as able to decide upon important matters of state. Their duties were therefore practically restricted to the election of the magistrates, whose names he usually presented to them. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Suetonius wrote: “At the elections for tribunes if there were not candidates enough of senatorial rank, he made appointments from among the knights, with the understanding that after their term they might remain in whichever order they wished. Morever, since many knights whose property was diminished during the civil wars did not venture to view the games from the fourteen rows through fear of the penalty of the law regarding theatres, he declared that none were liable to its provisions, if they themselves or their parents had ever possessed a knight's estate. He revised the lists of the people district by district, and to prevent the commons from being called away from their occupations too often because of the distributions of grain, he determined to give out tickets for four months' supply three times a year; but at their urgent request he allowed a return to the old custom of receiving a share every month. He also revived the old time election privileges, trying to put a stop to bribery by numerous penalties, and distributing to his fellow members of the Fabian and Scaptian tribes [Augustus was a member of the latter because of his connection with the Octavian family; with the former, through his adoption into the Julian gens] a thousand sesterces a man from his own purse on the day of the elections, to keep them from looking for anything from any of the candidates. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum — Divus Augustus” (“The Lives of the Caesars — The Deified Augustus”), written A.D. c. 110, “Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum,” 2 Vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 123-287]

“Considering it also of great importance to keep the people pure and unsullied by any taint of foreign or servile blood, he was most chary of conferring Roman citizenship and set a limit to manumission. When Tiberius requested citizenship for a Grecian dependent of his, Augustus wrote in reply that he would not grant it unless the man appeared in person and convinced him that he had reasonable grounds for the request; and when Livia asked it for a Gaul from a tributary province, he refused, offering instead freedom from tribute, and declaring that he would more willingly suffer a loss to his privy purse than the prostitution of the honour of Roman citizenship. Not content with making it difficult for slaves to acquire freedom, and still more so for them to attain full rights, by making careful provision as to the number, condition, and status of those who were manumitted, he added the proviso that no one who had ever been put in irons or tortured should acquire citizenship by any grade of freedom [i.e., even by iusta libertas, which conferred citizenship; slaves who had been punished for crimes or disgraceful acts became on manumission dediticii, or "prisoners of war"].

“He desired also to revive the ancient fashion of dress, and once when he saw in an assembly a throng of men in dark cloaks, he cried out indignantly, "Behold them Romans, lords of the world, the nation clad in the toga," [Verg., Aen. I.282], and he directed the aediles never again to allow anyone to appear in the Forum or its neighbourhood except in the toga and without a cloak.

Magistrates and Local Government Under Augustus

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: The republican magistrates continued to be elected. The consuls had little to do except preside over the Senate, but the consulship was still prestigious, and it opened the door for military commands and the governorship of senatorial provinces. Competition for the consulship was keen, and around 5 B.C. the number chosen each year was doubled by introducing suffect consuls: the two consuls would resign office after six months and their places would be taken by two suffects. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The praetors, eight until 23 B.C. then ten, and in Augustus' last years, 12, still had judicial duties; two of them became treasury officials after 23, managing the aerarium, and the next year they took over from the aediles the attractive duty of giving public games. The tribunes had nothing left to do, and the office became so unattractive to senators that in a.d. 12, Augustus opened it to the equites. Aediles had little to do except to repair streets and act as a small claims court in commercial cases, so there was, understandably, a dearth of candidates.

The quaestorship gave admission to the Senate. Twenty quaestors were elected each year and about half served in the provinces. Elections in the Centuriate Assembly for the praetors and consuls were lively, and Augustus had to take steps to control corruption. He had another control as well: by virtue of his proconsular imperium he could reject nominees, and present his own preferred list of candidates for the consulship and the praetorship. Other consuls could also commend nominees, and Roman politicians regularly canvassed for their candidates, but when Augustus canvassed, his commendation carried particular weight. It would be too much to say that the elections in the Centuriate Assembly were entirely free. The emperor Tiberius abolished them, and henceforth magistrates were elected in the Senate.

Imperial Cult and Revival of Old State Cults by Augustus

According to Encyclopedia.com Octavian began a systematic revival of the old state cults in the years before Actium (31), and then, as Augustus, founder of the Principate, he carried out this policy on a much wider scale. He instituted the Ludi saeculares in 17 B.C., and in 12 B.C., after the death of Lepidus, he assumed the office of Pontifex Maximus — held subsequently by all his successors until it was relinquished by Gratian, A.D. 382. He rebuilt temples throughout Rome, restored the old priesthoods, and required them to celebrate the rituals of their respective cults with the earlier regularity and pomp. He enlisted the help also of the great contemporary poets Horace, Virgil, and Ovid in his program of restoring the Old Roman cults and their celebration. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

But the most important of his religious innovations was the imperial cult. It was in part Hellenistic, but the emphasis on the public worship of the Genius of the emperor, especially in Rome and Italy, gave it a Roman character as well. It was intended to serve as an effective symbol of unity in the universal empire of Rome and also to promote a deeper loyalty on the part of the army to its imperator, or commander in chief. Gradually, the imperial cult and its priesthoods lost much of their appeal, but they enjoyed a marked revival in the period from Aurelian to Diocletian. Under the influence of the central administration and the model set by Rome, the religious cults of the Roman provinces, despite local aspects, assumed more and more the Roman pattern, at least in external form.

Augustus Worship and Religion Under Augustus

Augustus and the Roman goddess Cybele

Augustus held strong beliefs in traditional Roman religion. He restored over 80 temples and passed strict moral laws that mirrored older Roman values. With his encouragement of art and literature Augustus also tried to improve the religious and moral condition of the people. The old religion was falling into decay. With the restoration of the old temples, he hoped to bring the people back to the worship of the ancient gods. The worship of Juno, which had been neglected, was restored, and assigned to the care of his wife, Livia, as the representative of the matrons of Rome. Augustus tried to purify the Roman religion by discouraging the introduction of the foreign deities whose worship was corrupt. He believed that even a great Roman had better be worshiped than the degenerate gods and goddesses of Syria and Egypt; and so the Divine Julius was added to the number of the Roman gods. He did not favor the Jewish religion; and Christianity had not yet been preached at Rome. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Nina C. Coppolino wrote: “ Roman religion consisted of cult ritual, whose regular and traditional performance had a cohesive role in the state. The prestige of religious things had been dampened by neglect during the civil war years, but now religion was restored and promoted by Augustus for stability and for his own position in the state. Julius Caesar had traced the divine ancestry of his family to Venus and Mars, and when he was deified in 42 B.C., Augustus early in his career became the son of a god; in 29 B.C. he dedicated the Temple of the Divine Julius in the Roman Forum. Augustus's defeat of Antony and Cleopatra was portrayed as a victory of Roman over Egyptian gods; in 28 B.C. Augustus dedicated a temple to 'Actian Apollo' on Rome's Palatine Hill, where Augustus himself lived. Apollo was represented in a cult statue and in reliefs as both the god of vengeance against sacrilege like Antony's, and also as a bringer of peace. Augustus undertook the restoration of existing temples in the city, and he claims to have rebuilt eighty-two. (Res Gestae, 20.4) [Source: Nina C. Coppolino, Roman Emperors]

“After Actium Augustus was venerated as a divine king in Egypt, and the provinces in the east were allowed to erect temples to him in association with the goddess Roma. At Rome the senate made the traditional vows and prayers for his safety, and included him in annual prayers at the beginning of the year; even at Rome, however, the process of divination was begun. His name was included in the ancient Salian hymn to Mars or Quirinus. In 27 B.C. the cult of the Genius of Augustus was established, in which it was decreed that a libation should be poured to his guardian spirit at public and private banquets. The senate authorized a tribute to his moral leadership by setting up in the senate-house a golden shield celebrating his military virtue, clemency, justice, and social and religious responsibility; this shield was associated with the goddess Victoria and therefore implied god-given rule. Laurel trees sacred to Apollo were set up on either side of Augustus's house, and for rescuing citizens he was awarded the corona civica, made of oak leaves from the tree sacred to Jupiter. On coins of the period Jupiter's eagle, a symbol of apotheosis, was depicted with the civic crown and laurel branches.

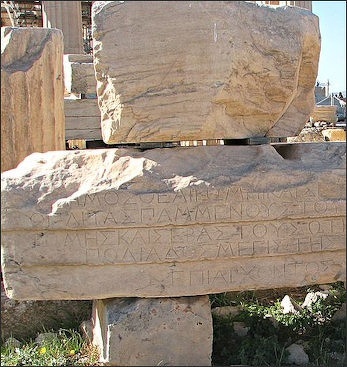

Halicarnassus Inscription Decreeing the Worship of Augustus

Inscription on the Temple of Rome and Augustus at the Athens Acropolis

Frederick C. Grant wrote in “Ancient Roman Religion: “This decree of the Provincial Assembly of Asia is dated 9 B.C. It sets forth the usual reasons for the worship of the emperor, i.e., the benefits of the Roman peace. At the proposal of the Proconsul, Paulus Fabius Maximus, the new year is to begin with the emperor's birthday, the ninth day before the Kalends of October (September 23). We have fragments of the decree, including even a Latin translation, from Priene, Apameia, Eumeneia, and Dorylaeum. Lines 1-29 give the letter of the Proconsul, lines 30-77 the decree of the Assembly. The Greek of the inscription is especially interesting for its use of terms also found in early Christian literature." [Source: "Dittenberger, OGIS, II. 458; P. Wendland, HRK, p. 409, no. 8; F. H. Gaertringen, Inschriften von Priene (1906), No. 105, “Ancient Roman Religion,” edited and translated by Frederick C. Grant,(The Liberal Arts Press, Inc., 1957) pp. 173f]

An inscription dedicated to Caesar Augustus from Halicarnassus dated after 2 B.C. reads: “"Since the eternal and deathless nature of the universe has perfected its immense benefits to mankind in granting us as a supreme benefit, for our happiness and welfare, Caesar Augustus, Father of his own Fatherland, divine Rome, Zeus Paternal, and Savior of the whole human race, in whom Providence has not only fulfilled but even surpassed the prayers of all men: land and sea are at peace, cities flourish under the reign of law, in mutual harmony and prosperity; each is at the very acme of fortune and abounding in wealth; all mankind is filled with glad hopes for the future, and with contentment over the present; [it is fitting to honor the god] with public games and with statues, with sacrifices and with hymns." [Source: British Museum Inscriptions, 894, Cf. P. Wendland, HRK, p. 410, no. 9]

Another Inscription under a statue of Caesar Augustus in Myra in Lycia reads: "The God Augustus, Son of God, Caesar, Autokrator [Autocrat, i.e., absolute ruler] of land and sea, the Evergetes (Benefactor) and Soter (Savior) of the whole cosmos, the people of Myra [have set up this statue]." [Source: E. Petersen, Reisen in Lykien, II, 43]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024