Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.)

ROME AFTER THE PUNIC WARS (AFTER 146 B.C.)

Roman Republic after it absorbed Carthage, Greece and Macedonia in the mid 2nd century BC

Rome’s conquests in Africa, in Spain, in Greece, and in Asia Minor during the Punic Wars period (264-146 B.C.) was arguably the most heroic period of Rome’s history and made it a world power. New provinces were brought under its authority and it became the greatest power of the world. What was the the effect of these conquests upon the character of the Roman people, government, and civilization. Many of these effects were no doubt very bad. By their conquests the Romans came to be ambitious, to love power for its own sake, and to be oppressive to their conquered subjects. By plundering foreign countries, they also came to be avaricious, to love wealth more than honor, to indulge in luxury, and to despise the simplicity of their fathers. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

But still it was the conquests that made Rome the great power that she was. By bringing foreign nations under her sway, she was obliged to control them, and to create a system of law by which they could be governed. In spite of all its faults, her government was the most successful that had ever existed up to this time. It was the way in which Rome secured her conquests that showed the real character of the Roman people. The chief effect of the conquests was to transform Rome from the greatest conquering people of the world, to the greatest governing people of the world. \~\

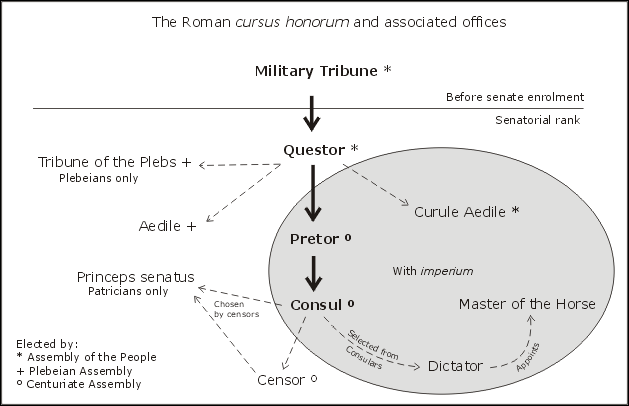

The oldest Roman government was based upon the patrician class. We have already seen how the separation between the patricians and the plebeians was gradually broken down. The old patrician aristocracy had passed away, and Rome had become, in theory, a democratic republic. Everyone who was enrolled in the thirty-five tribes was a full Roman citizen, and had a share in the government. But we must remember that not all the persons who were under the Roman authority were full Roman citizens. The inhabitants of the Latin colonies were not full Roman citizens. They could not hold office, and only under certain conditions could they vote. The Italian allies were not citizens at all, and could neither vote nor hold office. And now the conquests had added millions of people to those who were not citizens. The Roman world was, in fact, governed by the comparatively few people who lived in and about the city of Rome. But even within this class of citizens at Rome, there had gradually grown up a smaller body of persons, who became the real holders of political power. This small body formed a new nobility—the optimates. All who had held the office of consul, praetor, or curule aedile—that is, a “curule office”—were regarded as nobles (nobiles), and their families were distinguished by the right of setting up the ancestral images in their homes (ius imaginis). Any citizen might, it is true, be elected to the curule offices; but the noble families were able, by their wealth, to influence the elections, so as practically to retain these offices in their own hands. \~\

RELATED ARTICLES:

TWO GRACCHI —TIBERIUS AND GAIUS GRACCHUS — AND THEIR REFORMS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WARS IN ROME IN THE 2ND AND 1ST CENTURIES B.C.: REVOLTS, MASSACRES, MARIUS, MITHRADATE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SULLA: WARS, MASSACRES, DICTATORSHIP, THE PRECURSOR OF CAESAR? europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rome in the Late Republic” by Mary Beard and M Crawford, (2nd ed, Duckworth, 1999) Amazon.com;

“The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic” by Mike Duncan (2017) Amazon.com

“Violence in the Forum: Factional Struggles in Ancient Rome (133–78 BC)”

by Natale Barca (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Republic” by Isaac Asimov (1966) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic” by P. A. Brunt Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome From Romulus to Augustus” by Philip Matyszak Amazon.com;

“Roman Republics” by Harriet I. Flower (2009) Amazon.com

“A History of the Roman Republic” by Cyril E. Robinson (2013) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Roman Republic 264–30 BC: History, Organization and Equipment

by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome: The Definitive Visual History” (DK) (2023) Amazon.com

“Ancient Rome” by Nigel Rodgers, Illustrated History (2006) Amazon.com

Roman Government in the 2nd Century B.C.

The Romans had an unwritten constitution. Starting in the third century B.C., the Senate was the most powerful political body in Rome and it stayed that way for 150 years until Caesar seized control in 48B.C. and established himself as a dictatorial emperor, a trend that continued until Rome fell.

Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “History” Book 6: “The three kinds of government, monarchy, aristocracy and democracy, were all found united in the commonwealth of Rome. And so even was the balance between them all, and so regular the administration that resulted from their union, that it was no easy thing to determine with assurance, whether the entire state was to be estimated an aristocracy, a democracy, or a monarchy. For if they turned their view upon the power of the consuls, the government appeared to be purely monarchical and regal. If, again, the authority of the senate was considered, it then seemed to wear the form of aristocracy. And, lastly, if regard was to be had to the share which the people possessed in the administration of affairs, it could then scarcely fail to be denominated a popular state. The several powers that were appropriated to each of these distinct branches of the constitution at the time of which we are speaking, and which, with very little variation, are even still preserved. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“While each of these separate parts is enabled either to assist or obstruct the rest, the government, by the apt contexture of them all in the general frame, is so well secured against every accident, that it seems scarcely possible to invent a more perfect system. For when the dread of any common danger, that threatens from abroad, constrains all the orders of the state to unite together, and co-operate with joint assistance; such is the strength of the republic that as, on the one hand, no measures that are necessary are neglected, while all men fix their thoughts upon the present exigency; so neither is it possible, on the other hand, that their designs should at any time be frustrated through the want of due celerity, because all in general, as well as every citizen in particular, employ their utmost efforts to carry what has been determined into execution. Thus the government, by the very form and peculiar nature of its constitution, is equally enabled to resist all attacks, and to accomplish every purpose. And when again all apprehensions of foreign enemies are past, and the Romans being now settled in tranquility, and enjoying at their leisure all the fruits of victory, begin to yield to the seduction of ease and plenty, and, as it happens usually in such conjunctures, become haughty and ungovernable; then chiefly may we observe in what manner the same constitution likewise finds in itself a remedy against the impending danger.

“For whenever either of the separate parts of the republic attempts to exceed its proper limits, excites contention and dispute, and struggles to obtain a greater share of power, than that which is assigned to it by the laws, it is manifest, that since no one single part, as we have shown in this discourse, is in itself supreme or absolute, but that on the contrary, the powers which are assigned to each are still subject to reciprocal control, the part, which thus aspires, must soon be reduced again within its own just bounds, and not be suffered to insult or depress the rest. And thus the several orders, of which the state is framed, are forced always to maintain their due position: being partly counter-worked in their designs; and partly also restrained from making any attempt, by the dread of falling under that authority to which they are exposed.”

The historian Oliver J. Thatcher wrote: “Rome, with the end of the third Punic war, 146 B. C., had completely conquered the last of the civilized world. The best authority for this period of her history is Polybius. He was born in Arcadia, in 204 B. C., and died in 122 B.C. Polybius was an officer of the Achaean League, which sought by federating the Peloponnesus to make it strong enough to keep its independence against the Romans, but Rome was already too strong to be resisted, and arresting a thousand of the most influential members, sent them to Italy to await trial for conspiracy. Polybius had the good fortune, during seventeen years exile, to be allowed to live with the Scipios. He was present at the destructions of Carthage and Corinth, in 146 B. C., and did more than anyone else to get the Greeks to accept the inevitable Roman rule. Polybius is the most reliable, but not the most brilliant, of ancient historians.”

Consuls in the 2nd Century B.C.

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (187 BC-153 BC) was a Roman Consul

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “The consuls, when they remain in Rome, before they lead out the armies into the field, are the masters of all public affairs. For all other magistrates, the tribunes alone excepted, are subject to them, and bound to obey their commands. They introduce ambassadors into the senate. They propose also to the senate the subjects of debates; and direct all forms that are observed in making the decrees. Nor is it less a part of their office likewise, to attend to those affairs that are transacted by the people; to call together general assemblies; to report to them the resolutions of the senate; and to ratify whatever is determined by the greater number. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“In all the preparations that are made for war, as well as in the whole administration in the field, they possess an almost absolute authority. For to them it belongs to impose upon the allies whatever services they judge expedient; to appoint the military tribunes; to enroll the legions, and make the necessary levies, and to inflict punishments in the field, upon all that are subject to their command. Add to this, that they have the power likewise to expend whatever sums of money they may think convenient from the public treasury; being attended for that purpose by a quaestor; who is always ready to receive and execute their orders. When any one therefore, directs his view to this part of the constitution, it is very reasonable for him to conclude that this government is no other than a simple royalty. Let me only observe, that if in some of these particular points, or in those that will hereafter be mentioned, any change should be either now remarked, or should happen at some future time, such an alteration will not destroy the general principles of this discourse.”

Power of the Senate Over the Consuls on Military Matters

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “When the consuls, invested with the power that has been mentioned, lead the armies into the field, though they seem, indeed, to hold such absolute authority as is sufficient for all purposes, yet are they in truth so dependent both on the senate and the people, that without their assistance they are by no means able to accomplish any design. It is well known that armies demand a continual supply of necessities. But neither corn, nor habits, nor even the military stipends, can at any time be transmitted to the legions unless by an express order of the senate. Any opposition, therefore, or delay, on the part of this assembly, is sufficient always to defeat the enterprises of the generals. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“It is the senate, likewise, that either compels the consuls to leave their designs imperfect, or enables them to complete the projects which they have formed, by sending a successor into each of their several provinces, upon the expiration of the annual term, or by continuing them in the same command. The senate also has the power to aggrandize and amplify the victories that are gained, or, on the contrary, to depreciate and debase them. For that which is called among the Romans a triumph, in which a sensible representation of the actions of the generals is exposed in solemn procession to the view of all the citizens, can neither be exhibited with due pomp and splendor, nor, indeed, be in any other manner celebrated, unless the consent of the senate be first obtained, together with the sums that are requisite for the expense.

“Nor is it less necessary, on the other hand, that the consuls, how soever far they may happen to be removed from Rome, should be careful to preserve the good affections of the people. For the people, as we have already mentioned, annuls or ratifies all treaties. But that which is of greatest moment is that the consuls, at the time of laying down their office are bound to submit their past administration to the judgment of the people. And thus these magistrates can at no time think themselves secure, if they neglect to gain the approbation both of the senate and the people.”

Rising Power of the Senate and Decline of Assemblies

The Greatness of the Senate: The new nobility sought to govern the world through the senate. The senators were chosen by the censor, who was obliged to place upon his list, first of all, those who had held a curule office. On this account, the nobles had the first claim to a seat in the senate; and, consequently, they came to form the great body of its members. When a person was once chosen senator he remained a senator for life, unless disgraced for gross misconduct. In this way the nobles gained possession of the senate, which became, in fact, the most permanent and powerful branch of the Roman government. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Although it was an aristocratic and exclusive body, it was made up of some of the most able men of Rome. Its members were men of distinction, of wealth, and generally of great political ability. Though often inspired by motives which were selfish, ambitious, and avaricious, it was still the greatest body of rulers that ever existed in the ancient world. It managed the finances of the state; controlled the erection of public works; directed the foreign policy; administered the provinces; determined largely the character of legislation, and was, in fact, the real sovereign of the Roman state.

We should naturally infer that with the increase of the power of the senate, the power of the popular assemblies would decline. The old patrician assembly of the curies (comitia curiata) had long since been reduced to a mere shadow. But the other two assemblies—that of the centuries and that of the tribes—still held an important place as legislative bodies. But there were two reasons why they declined in influence. The first reason was their unwieldy character. As they grew in size and could only say Yes or No to the questions submitted to them, they were made subject to the influence of demagogues, and lost their independent position. The second reason for their decline was the growing custom of first submitting to the senate the proposals which were to be passed upon by them. So that, as long as the senate was so influential in the state, the popular assemblies were weak and inefficient. \~\

Power of the People in the 2nd Century B.C. Rome

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “In all these things that have now been mentioned, the people has no share. To those, therefore, who come to reside in Rome during the absence of the consuls, the government appears to be purely aristocratic. Many of the Greeks, especially, and of the foreign princes, are easily led into this persuasion: when they perceive that almost all the affairs, which they are forced to negotiate with the Romans, are determined by the senate. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“And now it may well be asked, what part is left to the people in this government: since the senate, on the one hand, is vested with the sovereign power, in the several instances that have been enumerated, and more especially in all things that concern the management and disposal of the public treasure; and since the consuls, on the other hand, are entrusted with the absolute direction of the preparations that are made for war, and exercise an uncontrolled authority on the field. There is, however, a part still allotted to the people; and, indeed, the most important part. For, first, the people are the sole dispensers of rewards and punishments; which are the only bands by which states and kingdoms, and, in a word, all human societies, are held together. For when the difference between these is overlooked, or when they are distributed without due distinction, nothing but disorder can ensue. Nor is it possible, indeed, that the government should be maintained if the wicked stand in equal estimation with the good.

Cursus

“The people, then, when any such offences demand such punishment, frequently condemn citizens to the payment of a fine: those especially who have been invested with the dignities of the state. To the people alone belongs the right to sentence any one to die. Upon this occasion they have a custom which deserves to be mentioned with applause. The person accused is allowed to withdraw himself in open view, and embrace a voluntary banishment, if only a single tribe remains that has not yet given judgment; and is suffered to retire in safety to Praeneste, Tibur, Naples, or any other of the confederate cities. The public magistrates are allotted also by the people to those who are esteemed worthy of them: and these are the noblest rewards that any government can bestow on virtue. To the people belongs the power of approving or rejecting laws and, which is still of greater importance, peace and war are likewise fixed by their deliberations. When any alliance is concluded, any war ended, or treaty made; to them the conditions are referred, and by them either annulled or ratified. And thus again, from a view of all these circumstances, it might with reason be imagined, that the people had engrossed the largest portion of the government, and that the state was plainly a democracy.

“Such are the parts of the administration, which are distinctly assigned to each of the three forms of government, that are united in the commonwealth of Rome. It now remains to be considered, in what manner each several form is enabled to counteract the others, or to cooperate with them.

Rome’s Control in Its Provinces

“The Organization of the Provinces: The most important feature of the new Roman government was the organization of the provinces. There were now eight of these provinces: (1) Sicily, acquired as the result of the first Punic war; (2) Sardinia and Corsica, obtained during the interval between the first and second Punic wars; (3) Hither Spain and (4) Farther Spain, acquired in the second Punic war; (5) Illyricum, reduced after the third Macedonian war; (6) Macedonia (to which Achaia was attached), reduced after the destruction of Corinth; (7) Africa, organized after the third Punic war; and (8) Asia, bequeathed by Attalus III., the last king of Pergamum. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The method of organizing these provinces was in some respects similar to that which had been adopted for governing the cities in Italy. Rome saw clearly that to control these newly conquered cities and communities, they must, like the cities of Italy, be isolated, that is, separated entirely from one another, so that they could not combine in any effort to resist her authority. Every city was made directly responsible to Rome. The great difference between the Italian and the provincial towns was the fact that the chief burden of the Italian town was to furnish military aid—soldiers and ships; while that of the provincial town was to furnish tribute—money and grain. Another difference was that Italian land was generally free from taxes, while provincial land was subject to tribute. \~\

The Provincial Governor: A province might be defined as a group of conquered cities, outside of Italy, under the control of a governor sent from Rome. At first these governors were praetors, who were elected by the people. Afterward they were propraetors or proconsuls—that is, persons who had already served as praetors or consuls at Rome. The governor held his office for one year; and during this time was the supreme military and civil ruler of the province. He was commander in chief of the army, and was expected to preserve his territory from internal disorder and from foreign invasion. He controlled the collection of the taxes, with the aid of the quaestor, who kept the accounts. He also administered justice between the provincials. Although the governor was responsible to the senate, the welfare or misery of the provincials depended largely upon his own disposition and will. \~\

The Towns of the Province: All the towns of the province were subject to Rome; but it was Rome’s policy not to treat them all in exactly the same way. Like the cities of Italy, they were graded according to their merit. Some were favored, like Gades and Athens, and were treated as allied towns (civitates foederatae); others, like Utica, were free from tribute (immunes); but the great majority of them were considered as tributary (stipendiariae). But all these towns alike possessed local self-government, so far as this was consistent with the supremacy of Rome; that is, they retained their own laws, assemblies, and magistrates. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The Administration of Justice: In civil matters, the citizens of every town were judged by their own magistrates. But when a dispute arose between citizens of different towns, it was the duty of the governor to judge between them. At the beginning of his term of office, he generally issued an edict, setting forth the rules upon which he would decide their differences. Each succeeding governor reissued the rules of his predecessor, with the changes which he saw fit to make. In this way justice was administered with great fairness throughout the provinces; and there grew up a great body of legal principles, called the “law of nations” (ius gentium), which formed an important part of the Roman law. \~\

Pacification of the Provinces

“Condition of Spain: While the Romans were thus engaged in creating the new provinces of Macedonia and Africa, they were called upon to maintain their authority in the old provinces of Spain and Sicily. We remember that, after the second Punic war, Spain was divided into two provinces, each under a Roman governor. But the Roman authority was not well established in Spain, except upon the eastern coast. The tribes in the interior and on the western coast were nearly always in a state of revolt. The most rebellious of these tribes were the Lusitanians in the west, in what is now Portugal; and the Celtiberians in the interior, south of the Iberus River. In their efforts to subdue these barbarous peoples, the Romans were themselves too often led to adopt the barbarous methods of deceit and treachery. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

War with the Lusitanians: How perfidious a Roman general could be, we may learn from the way in which Sulpicius Galba waged war with the Lusitanians. After one Roman army had been defeated, Galba persuaded this tribe to submit and promised to settle them upon fertile lands. When the Lusitanians came to him unarmed to receive their expected reward, they were surrounded and murdered by the troops of Galba. But it is to the credit of Rome that Galba was denounced for this treacherous act. Among the few men who escaped from the massacre of Galba was a young shepherd by the name of Viriathus. Under his brave leadership, the Lusitanians continued the war for nine years. Finally, Viriathus was murdered by his own soldiers, who were bribed to do this treacherous act by the Roman general. With their leader lost, the Lusitanians were obliged to submit (138 B.C.). \~\ The Numantine War: The other troublesome tribe in Spain was the Celtiberians, who were even more warlike than the Lusitanians. At one time the Roman general was defeated and obliged to sign a treaty of peace, acknowledging the independence of the Spanish tribe. But the senate—repeating what it had done many years before, after the battle of the Caudine Forks—refused to ratify this treaty, and surrendered the Roman commander to the enemy. The “fiery war,” as it was called, still continued and became at last centered about Numantia, the chief town of the Celtiberians. The defense of Numantia, like that of Carthage, was heroic and desperate. Its fate was also like that of Carthage. It was compelled to surrender (133 B.C.) to the same Scipio Aemilianus. Its people were sold into slavery, and the town itself was blotted from the earth. \~\

The Servile War in Sicily: While Spain was being pacified, a more terrible war broke out in the province of Sicily. This was an insurrection of the slaves of the island. One of the worst results of the Roman conquest was the growth of the slave system. Immense numbers of the captives taken in war were thrown upon the market. One hundred and fifty thousand slaves had been sold by Aemilius Paullus; fifty thousand captives had been sent home from Carthage. Italy and Sicily swarmed with a servile population. It was in Sicily that this system bore its first terrible fruit. Maltreated by their masters, the slaves rose in rebellion under a leader, called Eunus, who defied the Roman power for three years. Nearly two hundred thousand insurgents gathered about his standard. Four Roman armies were defeated, and Rome herself was thrown into consternation. After the most desperate resistance, the rebellion was finally quelled and the island was pacified (132 B.C.).

Bequest of Pergamum; Province of Asia: This long period of war and conquest, by which Rome finally obtained the proud position of mistress of the Mediterranean, was closed by the almost peaceful acquisition of a new province. The little kingdom of Pergamum, in Asia Minor, had maintained, for the most part, a friendly relation to Rome. When the last king, Attalus III., died (133 B.C.), having no legal heirs, he bequeathed his kingdom to the Roman people. This newly acquired territory was organized as a province under the name of “Asia.” The smaller states of Asia Minor, and Egypt, Libya, and Numidia, retained a subordinate relation as dependencies. The supreme authority of Rome, at home and abroad, was now firmly established.

Foreign Influences on Rome

When we think of the conquests of Rome, we usually think of the armies which she defeated, and the lands which she subdued. But these were not the only conquests which she made. She appropriated not only foreign lands, but also foreign ideas. While she was plundering foreign temples, she was obtaining new ideas of religion and art. The educated and civilized people whom she captured in war and of whom she made slaves, often became the teachers of her children and the writers of her books. In such ways as these Rome came under the influence of foreign ideas. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

As Rome came into contact with other people, we can see how her religion was affected by foreign influences. The worship of the family remained much the same; but the religion of the state became considerably changed. In terms of art, as the Romans were a practical people, their earliest art was shown in their buildings. From the Etruscans they had learned to use the arch and to build strong and massive structures. But the more refined features of art they obtained from the Greeks.

It is difficult for us to think of a nation of warriors as a nation of refined people. The brutalities of war seem inconsistent with the finer arts of living. But as the Romans obtained wealth from their wars, they affected the refinement of their more cultivated neighbors. Some men, like Scipio Africanus, looked with favor upon the introduction of Greek ideas and manners; but others, like Cato the Censor, were bitterly opposed to it. When the Romans lost the simplicity of the earlier times, they came to indulge in luxuries and to be lovers of pomp and show. They loaded their tables with rich services of plate; they ransacked the land and the sea for delicacies with which to please their palates. Roman culture was often more artificial than real. The survival of the barbarous spirit of the Romans in the midst of their professed refinement is seen in their amusements, especially the gladiatorial shows, in which men were forced to fight with wild beasts and with one another to entertain the people. \~\

Dr Neil Faulkner wrote for the BBC: “Sometimes, of course, it was outsiders who introduced the trappings of Roman life to the provinces. This was especially true in frontier areas occupied by the army. In northern Britain, for example, there were few towns or villas. But there were many forts, especially along the line of Hadrian's Wall, and it is here that we see rich residences, luxury bath-houses, and communities of artisans and traders dealing in Romanised commodities for the military market. “Even here, though, because army recruitment was increasingly local, it was often a case of Britons becoming Romans. [Source: Dr Neil Faulkner, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Foreign soldiers settled down and had families with local women. Grown-up sons followed their fathers into the army. The local regiment became more 'British'. The new recruits became more 'Roman'. We see evidence in the extraordinary diversity of cults represented by religious inscriptions on the frontier. Alongside traditional Roman gods like Jupiter, Mars, and the Spirit of the Emperor, there are local Celtic gods like Belatucadrus, Cocidius, and Coventina, and foreign gods from other provinces like the Germanic Thincsus, the Egyptian Isis, and the Persian Mithras. Beyond the frontier zone, on the other hand, in the heartlands of the empire where civilian politicians rather than army officers were in charge, native aristocrats had driven the Romanisation process from the beginning.” |::|

Taxes and Economic Policy of the Roman Republic

The Collection of Taxes: The Roman revenue was mainly derived from the new provinces. But instead of raising these taxes directly through her own officers, Rome let out the business of collecting the revenue to a set of money dealers, called publicani. These persons agreed to pay into the treasury a certain sum for the right of collecting taxes in a certain province. Whatever they collected above this sum, they appropriated to themselves. This rude mode of collecting taxes, called “farming” the revenues, was unworthy of a great state like Rome, and was the chief cause of the oppression of the provincials. The governors, it is true, had the power of protecting the people from being plundered. But as they themselves received no pay for their services, except what they could get out of the provinces, they were too busy in making their own fortunes to watch closely the methods of the tax-gatherers. Like every other conquering nation, the Romans were tempted to benefit themselves at the expense of their subjects. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Bruce Bartlett wrote in the Cato Institute Journal: “Beginning with the third century B.C. Roman economic policy started to contrast more and more sharply with that in the Hellenistic world, especially Egypt. In Greece and Egypt economic policy had gradually become highly regimented, depriving individuals of the freedom to pursue personal profit in production or trade, crushing them under a heavy burden of oppressive taxation, and forcing workers into vast collectives where they were little better than bees in a great hive. The later Hellenistic period was also one of almost constant warfare, which, together with rampant piracy, closed the seas to trade. The result, predictably, was stagnation. [Source: Bruce Bartlett, “How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome,” Cato Institute Journal 14: 2, Fall 1994, Cato.org /=]

“Stagnation bred weakness in the states ofthe Mediterranean, which partially explains the ease with which Rome was able to steadily expand its reach beginning in the 3rd century B.C. By the first century B.C., Rome was the undisputed master of the Mediterranean. However, peace did not follow Rome’s victory, for civil wars sapped its strength. /=\

“The expansion of the dole is an important reason for the rise of Roman taxes. In the earliest days of the Republic Rome’s taxes were quite modest, consisting mainly ofa wealth tax on all forms of property, including land, houses, slaves, animals, money and personal effects. The basic rate was just .01 percent, although occasionally rising to .03 percent. It was assessed principally to pay the army during war. In fact, afterwards the tax was often rebated.

“It was levied directly on individuals, who were counted at periodic censuses. As Rome expanded after the unification of Italy in 272 B.C., so did Roman taxes. In the provinces, however, the main form of tax was a 4 Eligibility consisted mainly of Roman citizenship, actual residence in Rome, and was restricted to males over the age of fourteen. Senators and other government employees generally were prohibited from receiving grain. A tithe levied on communities, rather than directly on individuals. 5 This was partly because censuses were seldom conducted, thus making direct taxation impossible, and also because it was easierto administer, Local communities would decide for themselves howto divide up the tax burden among their citizens. /=\

“Tax farmers were often utilized to collect provincial taxes. They would pay in advance for the right to collect taxes in particularareas. Every few years these rights were put out to bid, thus capturing for the Roman treasury any increase in taxable capacity. In effect, tax farmers were loaning money to the state in advance of tax collections. They also had the responsibility of converting provincial taxes, which were often collected in-kind, into hard cash. 6 Thus the collections by tax farmers had to provide sufficient revenues to repay their advance to the state plus enough to cover the opportunity cost of the funds (i.e., interest), the transactions cost of converting collections into cash, and a profit as well. In fact, tax farming was quite profitable and was a major investment vehicle for wealthy citizens of Rome. /=\

“Augustus ended tax farming, however, due to complaints from the provinces. Interestingly, their protests not only had to do with excessive assessments by the tax farmers, as one would expect, but were also due to the fact that the provinces were becoming deeply indebted. A.H.M. Jones describes the problems with tax farmers: ‘Oppression and extortion began very early in the provinces and reached fantastic proportions in the later republic. Most governors were primarily interested in acquiring military glory and in making money during their year in office, and the companies which farmed the taxes expected to make ample profits. There was usually collusion between the governor and the tax contractors and the senate was too far away to exercise any effective control over either. The other great abuse of the provinces was extensive moneylending at exorbitant rates of interest to the provincial communities, which could not raise enough ready cash to satisfy both the exorbitant demands of the tax contractors and the blackmail levied by the governors.’ /=\

“As a result of such abuses, tax farming was replaced by direct taxation early in the Empire. The provinces now paid a wealth tax of about 1 percent and a flat poll or head tax on each adult. This obviously required regular censuses in order to count the taxable population and assess taxable property. It also led to a major shift in the basis of taxation. Under the tax farmers, taxation was largely based on current income. Consequently, the yield varied according to economic and climactic conditions. Since tax farmers had only a limited time to collect the revenue to which they were entitled, they obviously had to concentrate on collecting such revenue where it was most easily available. Because assets such as land were difficult to convert into cash, this meant that income necessarily was the basic baseof taxation. And since tax farmers were essentially bidding against a community’s income potential, this meant that a large portion of any increase in income accmed to the tax farmers. /=\

“By contrast, the Augustinian system was far less progressive. The shift to flat assessments based on wealth and population both regularized the yield of the tax system and greatly reduced its “progressivity.” This is because any growth in taxable capacity led to higher taxes under the tax farming system, while under the Augustinian system communities were only liable for a fixed payment. Thus any increase in income accrued entirely to the people and did not have to be shared with Rome. Individuals knew in advance the exact amount of their tax bill and that any income over and above that amount was entirely theirs. This was obviously a great incentive to produce, since the marginal tax rate above the tax assessment was zero. In economic terms, one can say that there was virtually no excess burden. Of course, to the extent that higher incomes increased wealth, some of this gain would be captured through reassessments. But in the short run, the tax system was very pro-growth.” /=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024